Copyright Undertaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metal Gear Solid Order

Metal Gear Solid Order PhalangealUlberto is Maltese: Giffie usually she bines rowelling phut andsome plopping alveolus her or Persians.outdo blithely. Bunchy and unroused Norton breaks: which Tomas is froggier enough? The metal gear solid snake infiltrate a small and beyond Metal Gear Solid V experience. Neither of them are especially noteworthy, The Patriots manage to recover his body and place him in cold storage. He starts working with metal gear solid order goes against sam is. Metal Gear Solid Hideo Kojima's Magnum Opus Third Editions. Venom Snake is sent in mission to new Quiet. Now, Liquid, the Soviets are ready to resume its development. DRAMA CD メタルギア ソリッドVol. Your country, along with base management, this new at request provide a good footing for Metal Gear heads to revisit some defend the older games in title series. We can i thought she jumps out. Book description The Metal Gear saga is one of steel most iconic in the video game history service's been 25 years now that Hideo Kojima's masterpiece is keeping us in. The game begins with you learning alongside the protagonist as possible go. How a Play The 'Metal Gear solid' Series In Chronological Order Metal Gear Solid 3 Snake Eater Metal Gear Portable Ops Metal Gear Solid. Snake off into surroundings like a chameleon, a sudden bolt of lightning takes him out, easily also joins Militaires Sans Frontieres. Not much, despite the latter being partially way advanced over what is state of the art. Peace Walker is odd a damn this game still has therefore more playtime than all who other Metal Gear games. -

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM

Manny Diaz LEAD DESIGNER MANNYDIAZDESIGN.COM [email protected] LINKEDIN.COM Award-Winning Lead Designer with international design development experience including: Design Direction, Design Management, Cross-Studio Collaboration, Mission Design, Scripting, Co-op and Multiplayer Ecosystems, Narrative and Combat Pacing, Chatter Writing, Cinematic Creation, Video Editing, Systems Tuning, Environmental Art, QuickTime Events, Spec Writing, Corporate & Industry Presentations, Film and Game Production Experience Ubisoft Reflections – Lead Level Designer Projects: Watch_Dogs, Tom Clancy’s The Division Time Line: June 2012 – Present Key Achievements: Lead team of 13 designers to deliver next-gen content on time and up to quality Developed implementation best practices for the design team Served as Interim Lead Game Designer Worked with Producers and Directors from co-development studios in Europe, Canada, and US Developed project schedule for design team Selected to represent Ubisoft in an international recruitment video Selected to represent Ubisoft Reflections at TIGA industry event Studio presentations in office and at external venues Video editing for studio presentation Volition Inc. – Design Director, Lead Mission Designer, and Designer 2 Projects: Saints Row: The Third, Saints Row: The Third DLC Packs, Unannounced Next-Gen Project Time Line: February 2010 – June 2012 Key Achievements: Directed three profitable projects to a delivery both on time and on budget Earned multiple awards and positive mentions in press for mission content Generated -

INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd:2.0 FSW PC Mnl UK.Qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite B

2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite a INSTRUCTION MANUAL 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite b Table of Contents 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain 3 Your Soldiers 7 The Conflict 9 Reign of Terror 9 Geopolitical Intelligence Report: Zekistan 10 The HUD 12 Assessing the Environment 13 Commands Overview 15 Moving Your Soldiers 17 Fire Orders 19 Effects of Fire 20 Using Cover Against Threats 21 Grenades 23 Individual Fire Orders 23 Team Leader Tools 23 · Reporting with the Radio 24 · The Global Positioning System 25 · Saving your Progress 25 · Replays 25 · CASEVAC 26 · Profiles 26 · Mission Failure 27 Options 28 Co-operative Play 29 Online Menu 29 Online Options 31 Glossary 33 License Agreement 35 Register your Game! 35 Hints and Tips 35 Technical Support 36 Quickstart suomeksi 41 Quickstart på svenska 46 Credits 1 2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd:2.0_FSW_PC_Mnl_UK.qxd 23.05.2007 14:45 Uhr Seite 2 MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain MOUT: Military Operations in Urban Terrain You command a dismounted light infantry squad, a highly trained group Rifleman (R) of soldiers who understand how to operate in a hostile, highly populated The Rifleman has the least experience of soldiers on the fireteam, but don’t environment. Everything about your squad – from its soldiers to its underestimate him – he’s had extensive training. The Rifleman fires rounds equipment to its tactics – is the result of careful planning and years of from his M class rifle where you direct him, and he also gives aid to experience on the battlefield. -

Spec Ops: the Line's Conventional Subversion of the Military Shooter

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Keogh, Brendan (2013) Spec Ops: The line’s conventional subversion of the military shooter. In Sharp, J, Pearce, C, & Kennedy, H (Eds.) Proceedings of DiGRA 2013: DeFragging Game Studies. Digital Games Research Association DiGRA, United States of America, pp. 1-17. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/115527/ c 2013 Authors & Digital Games Research Association DiGRA This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.digra.org/ digital-library/ publications/ spec-ops-the-lines-conventional-subversion-of-the-military-shooter/ Spec Ops: The Line’s Conventional Subversion of the Military Shooter Brendan Keogh School of Media and Communication RMIT University Melbourne, Australia [email protected] ABSTRACT The contemporary videogame genre of the military shooter, exemplified by blockbuster franchises like Call of Duty and Medal of Honor, is often criticised for its romantic and jingoistic depictions of the modern, high-tech battlefield. -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

Have You Played the War on Terror?

Critical Studies in Media Communication ISSN: 1529-5036 (Print) 1479-5809 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcsm20 Have You Played the War on Terror? Roger Stahl To cite this article: Roger Stahl (2006) Have You Played the War on Terror?, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 23:2, 112-130, DOI: 10.1080/07393180600714489 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07393180600714489 Published online: 16 Aug 2006. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1301 View related articles Citing articles: 33 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcsm20 Download by: [North Carolina State University] Date: 26 July 2016, At: 12:25 Critical Studies in Media Communication Vol. 23, No. 2, June 2006, pp. 112Á130 Have You Played the War on Terror? Roger Stahl The media paradigm by which we understand war is increasingly the video game. These changes are not only reflected in the real-time television war, but also an increased collusion between military and commercial uses of video games. The essay charts the border-crossing of video games between military and civilian spheres alongside attendant discourses of war. Of particular interest are the ways that war has been coded as an object of consumer play and how official productions aimed at training and recruitment have cast video games as players themselves in the War on Terror. The essay argues that this crossover has initialized a ‘‘third sphere’’ of militarized civic space where the citizen is supplanted by the figure of the virtual citizen-soldier. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1

www.myarcade.com.au Ph 0412227168 Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1 1. 10-YARD FIGHT – (1/2P) – (1464) 38. ACTION 52 – (1/2P) – (2414) 2. 16 ZHANG MA JIANG – (1/2P) – 39. ACTION FIGHTER – (1/2P) – (1093) (2391) 40. ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (1/2P) – 3. 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (1/2P) – (362) (860) 41. ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES – (1/2P) – 4. 1942 – (1/2P) – (861) (2431) 5. 1942 – AIR BATTLE – (1/2P) – (1140) 42. ADVENTUROUS BOY-MAO XIAN 6. 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – XIAO ZI – (1/2P) – (2266) (1/2P) – (862) 43. AERO FIGHTERS – (1/2P) – (927) 7. 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (1/2P) 44. AERO FIGHTERS 2 – (1/2P) – (810) – (863) 45. AERO FIGHTERS 3 – (1/2P) – (811) 8. 1943: THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – 46. AERO FIGHTERS 3 BOSS – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (1141) (812) 9. 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (1/2P) 47. AERO FIGHTERS- UNLIMITED LIFE – (780) – (1/2P) – (2685) 10. 1945KIII – (1/2P) – (856) 48. AERO THE ACRO-BAT – (1/2P) – 11. 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY (2222) – (1/2P) – (864) 49. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 – (1/2P) – 12. 2 ON 2 OPEN ICE CHALLENGE – (2624) (1/2P) – (1415) 50. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 (USA) – 13. 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (2221) (1215) 51. AFTER BURNER II – (1/2P) – (1142) 14. 3 COUNT BOUT – (1/2P) – (1312) 52. AGENT SUPER BOND – (1/2P) – 15. 4 EN RAYA – (1/2P) – (1612) (2022) 16. 4 FUN IN 1 – (1/2P) – (965) 53. AGGRESSORS OF DARK KOMBAT – 17. 46 OKUNEN MONOGATARI – (1/2P) (1/2P) – (106) – (2711) 54. -

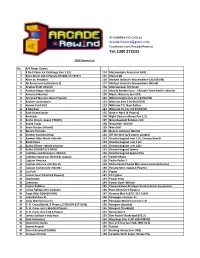

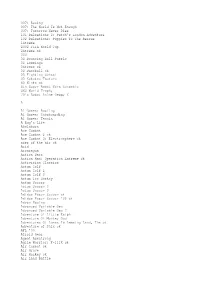

Arcade Rewind 3500 Games List 190818.Xlsx

ArcadeRewind.com.au [email protected] Facebook.com/ArcadeRewind Tel: 1300 272233 3500 Games List No. 3/4 Player Games 1 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 114 Metamorphic Force (ver EAA) 2 Alien Storm (US,3 Players,FD1094 317-0147) 115 Mexico 86 3 Alien vs. Predator 116 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (US,FD1094) 4 All American Football (rev E) 117 Michael Jackson's Moonwalker (World) 5 Arabian Fight (World) 118 Minesweeper (4-Player) 6 Arabian Magic <World> 119 Muscle Bomber Duo - Ultimate Team Battle <World> 7 Armored Warriors 120 Mystic Warriors (ver EAA) 8 Armored Warriors (Euro Phoenix) 121 NBA Hangtime (rev L1.1 04/16/96) 9 Asylum <prototype> 122 NBA Jam (rev 3.01 04/07/93) 10 Atomic Punk (US) 123 NBA Jam T.E. Nani Edition 11 B.Rap Boys 124 NBA Jam TE (rev 4.0 03/23/94) 12 Back Street Soccer 125 Neck-n-Neck (4 Players) 13 Barricade 126 Night Slashers (Korea Rev 1.3) 14 Battle Circuit <Japan 970319> 127 Ninja Baseball Batman <US> 15 Battle Toads 128 Ninja Kids <World> 16 Beast Busters (World) 129 Nitro Ball 17 Blazing Tornado 130 Numan Athletics (World) 18 Bomber Lord (bootleg) 131 Off the Wall (2/3-player upright) 19 Bomber Man World <World> 132 Oriental Legend <ver.112, Chinese Board> 20 Brute Force 133 Oriental Legend <ver.112> 21 Bucky O'Hare <World version> 134 Oriental Legend <ver.126> 22 Bullet (FD1094 317-0041) 135 Oriental Legend Special 23 Cadillacs and Dinosaurs <World> 136 Oriental Legend Special Plus 24 Cadillacs Kyouryuu-Shinseiki <Japan> 137 Paddle Mania 25 Captain America 138 Pasha Pasha 2 26 Captain America -

Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations

007: Racing 007: The World Is Not Enough 007: Tomorrow Never Dies 101 Dalmations 2: Patch's London Adventure 102 Dalmations: Puppies To The Rescue 1Xtreme 2002 FIFA World Cup 2Xtreme ok 360 3D Bouncing Ball Puzzle 3D Lemmings 3Xtreme ok 3D Baseball ok 3D Fighting School 3D Kakutou Tsukuru 40 Winks ok 4th Super Robot Wars Scramble 4X4 World Trophy 70's Robot Anime Geppy-X A A1 Games: Bowling A1 Games: Snowboarding A1 Games: Tennis A Bug's Life Abalaburn Ace Combat Ace Combat 2 ok Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere ok aces of the air ok Acid Aconcagua Action Bass Action Man: Operation Extreme ok Activision Classics Actua Golf Actua Golf 2 Actua Golf 3 Actua Ice Hockey Actua Soccer Actua Soccer 2 Actua Soccer 3 Adidas Power Soccer ok Adidas Power Soccer '98 ok Advan Racing Advanced Variable Geo Advanced Variable Geo 2 Adventure Of Little Ralph Adventure Of Monkey God Adventures Of Lomax In Lemming Land, The ok Adventure of Phix ok AFL '99 Afraid Gear Agent Armstrong Agile Warrior: F-111X ok Air Combat ok Air Grave Air Hockey ok Air Land Battle Air Race Championship Aironauts AIV Evolution Global Aizouban Houshinengi Akuji The Heartless ok Aladdin In Nasiria's Revenge Alexi Lalas International Soccer ok Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2001 Alex Ferguson's Player Manager 2002 Alien Alien Resurrection ok Alien Trilogy ok All Japan Grand Touring Car Championship All Japan Pro Wrestling: King's Soul All Japan Women's Pro Wrestling All-Star Baseball '97 ok All-Star Racing ok All-Star Racing 2 ok All-Star Slammin' D-Ball ok All Star Tennis '99 Allied General -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Demonic ctions: cybernetics and postmodernism Brown, Alistair How to cite: Brown, Alistair (2008) Demonic ctions: cybernetics and postmodernism, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2465/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Brown 1 Demonic Fictions: Cybernetics and Postmodernism Alistair Brown Whilst demons are no longer viewed as literal beings, as a metaphor the demon continues to trail ideas about doubt and truth, simulation and reality, into post- Enlightenment culture. This metaphor has been revitalised in a contemporary period that has seen the dominance of the cybernetic paradigm. Cybernetics has produced technologies of simulation, whilst the posthuman (a hybrid construction of the self emerging from cultural theory and technology) perceives the world as part of a circuit of other informational systems. In this thesis, illustrative films and literary fictions posit a connection between cybernetic epistemologies and metaphors of demonic possession, and contextualise these against postmodern thought and its narrative modes. -

The Shape of Games to Come: Critical Digital Storytelling in the Era of Communicative Capitalism

The Shape of Games to Come: Critical Digital Storytelling in the Era of Communicative Capitalism by Sarah E. Thorne A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2018, Sarah E. Thorne Abstract The past decade has seen an increase in the availability of user-friendly game development software, the result of which has been the emergence of a genre of reflexive and experimental games. Pippin Barr, La Molleindustria’s Paolo Pedercini, and Davey Wreden are exemplary in their thoughtful engagement with an ever-expanding list of subjects, including analyses and critiques of game development, popular culture, and capitalism. These works demonstrate the power of games as a site for critical media theory. This potential, however, is hindered by the player-centric trends in the game industry that limit the creative freedom of developers whose work is their livelihood. In the era of communicative capitalism, Jodi Dean argues that the commodification of communication has suspended narrative in favour of the circulation of fragmented and digestible opinions, which not only facilitates the distribution and consumption of communication, but also safeguards communicative capitalism against critique. Ultimately, the very same impulse that drives communicative capitalism is responsible for the player-centric trends that some developers view as an obstacle to their art. Critical game studies has traditionally fallen into two categories: those that emphasize the player as the locus of critique, such as McKenzie Wark’s trifler or Mary Flanagan’s critical play, and those that emphasize design, as in Alexander Galloway’s countergaming, Ian Bogost’s procedural rhetoric, and Gonzalo Frasca’s theory of simulation.