PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

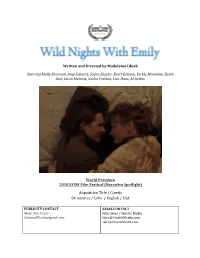

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

Photo Journalism, Film and Animation

Syllabus – Photo Journalism, Films and Animation Photo Journalism: Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Need and importance, Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). subject of photo picture sources, Photojournalists are able to enjoy a working environment that gets them out from behind a desk and into the world. -

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme Nr. 94 (Mai 2010)

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme -Kurzübersicht- Detaillierte Informationen finden Sie auf unserer Website und in unse- rem 14tägigen Newsletter Nr. 94 (Mai 2010) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS Talstr. 11 - 70825 Korntal Tel.: (0711) 83 21 88 - Fax: (0711) 8 38 05 18 INTERNET: www.laserhotline.de e-mail: [email protected] Katalog DVD BRD (Spielfilme) Nr. 94 Mai 2010 (500) Days of Summer 10 Dinge, die ich an dir 20009447 25,90 EUR 12 Monkeys (Remastered) 20033666 20,90 EUR hasse (Jubiläums-Edition) 20009576 25,90 EUR 20033272 20,90 EUR Der 100.000-Dollar-Fisch (K)Ein bisschen schwanger 20022334 15,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags 20032742 18,90 EUR Die 10 Gebote 20000905 25,90 EUR 20029526 20,90 EUR 1000 - Blut wird fließen! (Traum)Job gesucht - Will- 20026828 13,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags - High Noon kommen im Leben Das 10 Gebote Movie (Arthaus Premium, 2 DVDs) 20033907 20,90 EUR 20032688 15,90 EUR 1000 Dollar Kopfgeld 20024022 25,90 EUR 20034268 15,90 EUR .45 Das 10 Gebote Movie Die 120 Tage von Bottrop 20024092 22,90 EUR (Special Edition, 2 DVDs) Die 1001 Nacht Collection – 20016851 20,90 EUR 20032696 20,90 EUR Teil 1 (3 DVDs) .com for Murder 20023726 45,90 EUR 13 - Tzameti (k.J.) 20006094 15,90 EUR 10 Items or Less - Du bist 20030224 25,90 EUR wen du triffst 101 Dalmatiner (Special [Rec] (k.J.) 20024380 20,90 EUR Edition) 13 Dead Men 20027733 18,90 EUR 20003285 25,90 EUR 20028397 9,90 EUR 10 Kanus, 150 Speere und [Rec] (k.J.) drei Frauen 101 Reykjavik 13 Dead Men (k.J.) 20032991 13,90 EUR 20024742 20,90 EUR 20006974 25,90 EUR 20011131 20,90 EUR 0 Uhr 15 Zimmer 9 Die 10 Regeln der Liebe 102 Dalmatiner 13 Geister 20028243 tba 20005842 16,90 EUR 20003284 25,90 EUR 20005364 16,90 EUR 00 Schneider - Jagd auf 10 Tage die die Welt er- Das 10te Königreich (Box 13 Semester - Der frühe Nihil Baxter schütterten Set) Vogel kann mich mal 20014776 20,90 EUR 20008361 12,90 EUR 20004254 102,90 EUR 20034750 tba 08/15 Der 10. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Srinivasan College of Arts and Science

SRINIVASAN COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (Affiliated to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli) Perambalur-621 212 COURSE MATERIAL OF INTRODUCTION TO FILM STUDIES-16ACCJM8 For II B.A Journalism and Mass Communication Prepared by V.ChandraChowdry & Dr.S.Revathi Core Course VIII - Introduction to Film Studies Objective: To enable the students understand and appreciate the historical, social, political, cultural and economical aspects of film locally, nationally and globally. UNIT I Film as a medium: Characteristic - Film perception: levels of understanding - Film theory and semiotics - formalism and neo formalism - film language - film and psycho - analysis - film and cultural identity: hermeneutics, reception aesthetics and film interpretation. UNIT II Film forms: narrative and non-narrative - Acting, costume and music - Film and post modernism -post structuralism and deconstruction. Impressionism, expressionism, and surrealism. UNIT III Film production: Visualisation - script - writing - characterization - storyboard - tools and techniques. Continuity style: composing shots - spatial (mise en scene) - temporal (montage) - Camera shots: pan, crane, tracking, and transition. Sound in cinema: dimensions and functions. UNIT IV Film festival - Film awards - Film institute’s censorship certification - Cinema theatres and Projections. UNIT V Film business and Industry - Economic- finance and business of film - film distribution - import and export of films - regional cinema with special reference to Tamil cinema. Budgeting and schedules UNIT-I Movie Film, also called movie or motion picture, is a visual art used to simulate experiences that communicate ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty or atmosphere by the means of recorded or programmed moving images along with other sensory stimulations.[1] The word "cinema", short for cinematography, is often used to refer to filmmaking and the film industry, and to the art form that is the result of it. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE