Four Challenges for International Water Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

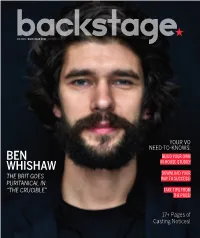

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published Or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures)

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures): “An Unfrozen North”. By J. Madeleine Nash, 19 February 2018, High Country News, https://www.hcn.org/issues/50.3/an-unfrozen-north “Exploding Killer Lakes”. By Taylor Mayol, 2 March 2016, OZY, http://www.ozy.com/flashback/exploding-killer-lakes/65346 “Arctic Sunlight Can Speed Up the Greenhouse Effect”. By Susan Linville, Moments in Science, Posted February 27, 2015. http://indianapublicmedia.org/amomentofscience/arctic-sunlight-speed-greenhouse- effect/ http://ns.umich.edu/new/releases/22338-climate-clues-sunlight-controls-the-fate-of-carbon- released-from-thawing-arctic-permafrost http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2014/aug/science-study-sunlight-not-microbes-key-co2- arctic http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140821141548.htm http://www.aninews.in/newsdetail9/story180338/it-039-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide- in-arctic.html http://www.sciencecodex.com/sunlight_not_microbes_key_to_co2_in_arctic-140097 http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-08/uom-sct081514.php http://phys.org/news/2014-08-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic.html http://www.laboratoryequipment.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-permafrosts-released- carbon http://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/it-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide-in- arctic-114082200579_1.html http://www.eurasiareview.com/22082014-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic/ http://www.rdmag.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-carbon-released-thawing-arctic- permafrost http://zeenews.india.com/news/eco-news/sunlight-not-bacteria-key-to-co2-in-arctic_956515.html -

Impact Campaigns, Summarised in Impact Reports Which Are Published on Our Website

@britdoc britdoc.org 2 The Art of Impact. STORIES CAN CONQUER FEAR, YOU KNOW. THEY CAN MAKE BEN OKRI POET THE HEART LARGER. 04 The Art of Impact. The Impact of Art. 05 OUR ABOUT FUNDS OUR BRITDOC p34 p06 FILMS p40 Helping good films be great Engaging new HELLO partners GOOD PITCH p82 IMPACT Sharing our FIELD GUIDE learning p124 We are a nonprofit, founded in 2005, committed to enabling great Building new documentary films and connecting audiences them to audiences. Doing and measuring Based in London and New York, we work with filmmakers and partners globally, reaching IMPACT DOC audiences all over the world. AWARD ACADEMY p118 p94 In this book you can find out SOMETHING more about what we do and IMPACT REAL how it fits into our five DISTRIBUTION p102 interconnected strategic areas. p106 06 The Art of Impact. The Impact of Art. 07 “For many years, BRITDOC has spotted and supported the most urgent projects – OUR MISSION OUR DRIVING PRINCIPLE nurturing them with love, ensuring they make a difference. But gradually We befriend great filmmakers, Great documentaries enrich BRITDOC became more support great films, broker the lives of individuals. They than a fund. It is, by now, new partnerships, build have a unique ability to the forum for our most important conversations new business models, share engage and connect people, in nonfiction cinema.” knowledge and develop transform communities and Joshua Oppenheimer Director audiences globally. improve societies. “ BRITDOC are experts in We aim to lead by example — That’s why we are dedicated collaboration, innovation and rapid prototyping.” innovate, share and be copied, to the Impact of Art, and the Cara Mertes and innovate again. -

Produced with the Participation of Blue Ice Docs

Cinephil presents An Ink & Pepper / Big World Cinema / Appian Way production In Association with Gabriel Films Produced with the participation of Blue Ice Docs A film by Anjali Nayar World Premiere at 80 minutes English, Liberian English • • Canada/South Africa/Kenya 2017 • Contacts at TIFF: Producer: Producer: Steven Markovitz Anjali Nayar Big World Cinema Ink & Pepper Productions E: [email protected] E: T: +27 83 2611 044 T: +1- 415-910-4625 Sales Agent: Publicist: Philippa Kowarsky Charlene Coy Cinephil C2C Communications E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: +972 3 566 4129 T: +1-416-451-1471 Tagline: No more business as usual Logline With a network of dedicated citizen reporters by his side, seasoned Liberian activist Silas Siakor challenges the corrupt and nepotistic status quo in his fight for local communities. Synopsis Liberian activist, Silas Siakor is a tireless crusader, fighting to crush corruption and environmental destruction in the country he loves. Through the focus on one country, Silas is a global tale that -

Film Studies

Film Studies SAMPLER INCLUDING Chapter 5: Rates of Exchange: Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 27: The World Viewed: Documentary Observing and the Culture of Surveillance From A Companion to Contemporary Documentary Film Edited by Alexandra Juhasz and Alisa Lebow Chapter 14: Nairobi-based Female Filmmakers: Screen Media Production between the Local and the Transnational From A Companion to African Cinema Edited by Kenneth W. Harrow and Carmela Garritano 5 Rates of Exchange Human Trafficking and the Global Marketplace Leshu Torchin Introduction1 Since 1992, the world has witnessed significant geopolitical shifts that have exacer- bated border permeability. The fall of the “iron curtain” in Eastern Europe and the consolidation of the transnational constitutional order of the European Union have facilitated transnational movement and given rise to fears of an encroaching Eastern threat, seen in the Polish plumber of a UKIP2 fever dream. Meanwhile, global business and economic expansion, granted renewed strength through enhance- ments in communication and transportation technologies as well as trade policies implemented through international financial institutions, have increased demand for overseas resources of labor, goods, and services. This is not so much a new phenomenon, as a rapidly accelerating one. In the wake of these changes, there has been a resurgence of human trafficking films, many of which readily tap into the gendered and racialized aspects of the changing social landscape (Andrjasevic, 2007; Brown et al., 2010). The popular genre film, Taken (Pierre Morel, France, 2008) for instance, invokes the multiple anxieties in a story of a young American girl who visits Paris only to be kidnapped by Albanian mobsters and auctioned off to Arab sheiks before she is rescued by her renegade, one-time CIA agent father. -

Smarter Crowdsourcing for Anti-Corruption a Handbook of Innovative Legal, Technical, and Policy Proposals and a Guide to Their Implementation

SMARTER CROWDSOURCING ANTI-CORRUPTION Smarter Crowdsourcing for Anti-corruption A Handbook of Innovative Legal, Technical, and Policy Proposals and a Guide to their Implementation Beth Simone Noveck Kaitlin Koga Rafael Aceves Garcia Hannah Deleanu Dinorah Cantú-Pedraza APRIL 2018 anticorruption.smartercrowdsourcing.org SMARTER CROWDSOURCING anticorruption.smartercrowdsourcing.org ANTI-CORRUPTION Acknowledgments We acknowledge the contribution to the execution of this project to the following individuals from the Inter- American Development Bank (IDB): ‣ Nicolás Dassen, Senior Specialist, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Arturo Muente, Senior Specialist, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Mario Sanginés, Principal Specialist in Mexico, Modernization of the Public Sector (ICS/IFD) ‣ Darinka Vásquez Jordan, Consultant, Innovation in Citizen Services (ICS/IFD) ‣ Michelle Marshall, Consultant, Knowledge Management and Open Innovation (KNM/KNL) Copyright © 2018 Inter-American Development Bank (“IDB”). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons IGO 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (CC-IGO 3.0 BY-NC-SA) (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode) and may be reproduced with attribution to the IDB and for any non-commercial purpose in its original or in any derivative form, provided that the derivative work is licensed under the same terms as the original. The IDB is not liable for any errors or omissions contained in derivative works and does not guarantee that such derivative works will not infringe the rights of third parties. Any dispute related to the use of the works of the IDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. -

FILM SCREENING SCHEDULE November 05-29, 2013 Monday to Friday (05:00 – 06:00 Pm) at CMS, Saket Community Centre, New Delhi, India

FILM SCREENING SCHEDULE November 05-29, 2013 Monday to Friday (05:00 – 06:00 pm) at CMS, Saket Community Centre, New Delhi, India November 05 - 08, 2013 Date & Day Category Title of the Film Duration Filmmaker Corbett's Legacy 00:35:45 Naresh Bedi Biodiversity (Indian) 05-11-2013 Tuesday How Bird-Catcher Became Animation (International) 00:03:55 Kate Podlipskaya Bird-Admirer 06-11-2013 Biodiversity (International) People of a Feather 00:53:21 Joel Heath Wednesday 07-11-2013 Dereck and Beverly Feature Film (International) The Last Lion 01:27:00 Thursday Joubert Climate Change and 08-11-2013 The Attack of 1.5 Sustainable Technologies 01:01:13 Jang-Won-Joon Friday Degrees, The Sea of Jeju (International) November 11 - 15, 2013 Date & Day Category Title of the Film Duration Filmmaker Biodiversity (Indian) Gaur in my Garden 00:28:48 Rita Banerji 11-11-2013 Climate Change and Tales of Gorakhpur: Path Monday Sustainable Technologies Towards a Climate 00:19:39 Rishu Nigam (Indian) Resilient Future Raviraj Chandrakant Green Ganesh Festival 00:25:49 12-11-2013 Environmental Conservation Naik Tuesday (Indian) Nenmanikyam (Golden 00:28:16 M Venukumar Grain) Environmental Conservation Stand 00:46:00 Nicolas Teichrob (International) 13-11-2013 Nature, like a child need Animation (International) 00:00:59 Michael Poletaew Wednesday of your care! Ashwini N, Pooja T Animation (Indian) Save Tree 00:04:27 and Sneha S 14-11-2013 Biodiversity (International) The Moor 00:50:04 Jan Haft Thursday Animation (International) POP 00:03:08 Rachel Moore 15-11-2013 Feature Film (Indian) Ajoba (Grand Father) 01:50:39 Sujay Dahake Friday 1 November 18 - 22, 2013 Date & Day Category Title of the Film Duration Filmmaker 18-11-2013 Environmental Conservation A2 (A2-B-C) 01:09:57 Ian Thomas Ash Monday (International) Climate Change and RE:source, RE:duce, 19-11-2013 Sustainable Technologies RE:cycle, RE:use Planet 01:25:28 Eskil Hardt Tuesday (International) RE:think 20-11-2013 Environmental Conservation Char.. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Updated July 2020

G. Kling, p. 1 George W. Kling, CV Summary (Full CV following) Research Publications: (130+ total) Highlighted (lead or corresponding author on 9 of the following): Science 236:169 Nature 337:215 Nature Communications 8:772 Science 237:1022 Nature 348:201 PNAS 102:14185 Science 251:298 Nature 368:405 PNAS 110:3429 Science 265:1568 Nature 408:149 PNAS 115:3 Science 345:925 Nature 551:457 External Awards: - Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1997 – . - U. S. National Science Foundation Presidential Faculty Fellow, 1995 – 2000. - U. S. National Academy of Sciences Young Investigator Award, 1993 - 1994. - Republic of Cameroon, Presidential Medal for Service (disaster reduction), 2016. - United Nations Sasakawa Award, Certificate of Merit for Disaster Reduction, Nyos-Monoun Degassing Program, (as Chair of Advisory Committee), 2001. - Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography, John H. Martin Award, 2016. - Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography, Ruth Patrick Award, 2007. Grants: - Total: 40 awards (34 NSF, plus EPA, NASA, USAID, Hewlett Foundation, National Geographic Society) - Current: 4 NSF, 1 NASA - Amount: $56,835,000 total awarded; $13,608,000 to Kling Teaching and Mentoring: - 10 separate courses taught (not including seminars) - Chair of 11 Ph.D., 6 M.S.; Committee member of 34 Ph.D., 4 M.S., 6 Honors Theses - 30 students supervised for undergraduate research (15 by NSF-REU funding) - Grant funding from NSF and the Hewlett Foundation to develop an undergraduate curriculum development testbed, and for developing the first academic minor at U of M Outreach (published or broadcast interviews about my research): - 300+ articles (e.g., National Geographic, Smithsonian, Discover, GEO, World Book, Science News, NSF Frontiers, New York Times, BBC News, New Scientist, Economist) - 13 articles in Science and Nature - 8 television films (BBC, National Geographic, Discovery Channel, PBS, History Channel, Learning Channel, Weather Channel) - 25 T.V. -

ABN AMRO Human Rights Report 2018

Putting people centre stage ABN AMRO Group N.V. Human Rights Report 2018 1 Preface On a cold December day in Paris in 1948, representatives Where workers are free to join unions and bargain Collaboration, underpinned by a shared courage of from all across the world drafted the Universal Declaration collectively, where peoples’ land rights do not get conviction, is the common thread throughout the of Human Rights. In human history terms, this was a trumped because they live in an area with a wealth initiatives and programmes we describe in our report. monumental occasion. Not only because this declaration of natural resources, and where citizens’ rights to No single entity can do this alone. We all have a role recognised the rights of all the citizens of this planet, privacy and health are respected and upheld by all. to play. Colleagues, together with business partners, but also because people from various backgrounds, NGOs, suppliers and clients have worked to make both professionally and culturally, worked tirelessly This report, ABN AMRO’s second Human Rights Report, our aspirations a reality and indeed to stretch our together for the greater good of humanity. The greater outlines our standards and our programmes in relation own ambitions even further. good of our planet. to human rights. It details the impact we are making as a bank internally through our own policies, procedures “I am proud of the steps we are taking, but At ABN AMRO we believe we have a role to play in and partnerships, as well as the progress we are making mindful of the fact that the path from theory fulfilling the goals, sentiments and principles as outlined in advocating for human rights in the business community. -

Klein, N. (2014). This Changes Everything: Capitalism Vs. the Climate

Klein, N. (2014). This changes everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. New York: Simon & Shuster. Introduction: One Way or Another, Everything Changes "Most projections of climate change presume that future changes-greenhouse gas emissions, temperature increases and effects such as sea level rise-will happen incrementally. A given amount of emission will lead to a given amount of temperature increase that will lead to a given amount of smooth incremental sea level rise. However, the geological record for the climate reflects instances where a relatively small change in one element of climate led to abrupt changes in the system as a whole. In other words, pushing global temperatures past certain thresholds could trigger abrupt, unpredictable and potentially irreversible changes that have massively disruptive and large-scale impacts. At that point, even if we do not add any additional CO2 to the atmosphere, potentially unstoppable processes are set in motion. We can think of this as sudden climate brake and steering failure where the problem and its consequences are no longer something we can control." -Report by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world's largest general scientific society, 20141 "I love that smell of the emissions." -Sarah Palin, 20112 A voice came over the intercom: would the passengers of Flight 3935, scheduled to depart Washington, D.C., for Charleston, South Carolina, kindly collect their carry-on luggage and get off the plane. They went down the stairs and gathered on the hot tarmac. There they saw something unusual: the wheels of the US Airways jet had sunk into the black pavement as if it were wet cement. -

Gun-Runners-Cinefiche-V 03 Mr.Pdf

PRODUCED BY THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA PRODUIT PAR L’OFFICE NATIONAL DU FILM DU CANADA Photos: Georgina Goodwin & Tobin Jones THE FILM LE FILM When it comes to world-class marathon runners, Kenyans are considered Lorsqu’il s’agit de produire des marathoniens de calibre mondial, la the cream of the crop. Particularly those from Kenya’s Rift Valley. These réputation du Kenya n’est plus à faire. Mais certains des plus grands athletes have won marathons in London, New York and Berlin, and have coureurs kényans ne sont mus ni par la gloire ni par la fortune : certains set countless world records. But some of Kenya’s top runners aren’t d’entre eux sont des hors-la-loi recherchés par les autorités de leur running for fame and fortune. Some are wanted warriors, running for pays et courent pour sauver leur vie. their lives. Des années durant, Julius Arile et Robert Matanda évoluent parmi For years, Julius Arile and Robert Matanda thrive among the roaming les hors-la-loi qui sèment la terreur dans les campagnes du nord du bands of warriors that terrorize the North Kenyan countryside. By the Kenya. Ces jeunes ne savent que commettre des vols de bestiaux, time they reach their mid-twenties, stealing cattle, raiding and running des cambriolages et fuir la police. Aussi, lorsqu’ils disparaissent from the police is the only life they know. So when both warriors soudainement, leur entourage conclut à leur mort ou à leur arrestation. suddenly disappear from the bush, many of their peers assume they En fait, ils vont troquer leur fusil contre des chaussures de course are dead or have been arrested. -

Fiscal Year Annual Report 01 WELCOME Sundance Institute Annual Report

Sundance Institute Fiscal Year Annual Report 01 WELCOME Sundance Institute Annual Report Welcome As we navigate another year of global events and changes that are defining our times, we again turn to artists for insight and inspiration. Artists who open our eyes to new worlds and new ways of understanding different perspectives. Artists who harness the power of storytelling to activate important conversations and actions. With deep and sustaining support provided to more than 1,400 artists, including over $16 million invested in labs, grants, and fellowships, Sundance Institute’s commitment to support the visionary work of independent artists is uncompromising this year. We’re excited to share with you our 2019 Annual Report that illuminates three critical pillars of our mission in action: supporting the most talented independent artists around the world and advancing their creative practices; fostering an inclusive community to hear from underrepresented voices on the screen and stage; and catalyzing the impact of independent storytelling. Thank you to the dedicated staff, volunteers, and community of supporters of Sundance Institute who all come together in the shared belief that a world more connected through storytelling and a common humanity is a better world. We look forward to what’s possible in the year ahead. Robert Redford President & Founder Pat Mitchell Chair, Board of Trustees Robert Redford Pat Mitchell 02 WELCOME Sundance Institute Annual Report Welcome I am constantly amazed by the curiosity and passion of artists, and inspired by their creative journeys—a process fueled by reflection, risk-taking, and an openness to new possibilities. In 2019, Sundance Institute continued its own creative journey as we saw great opportunities for learning and evolving our own work to respond to the changing environment for artists around the world.