Smarter Crowdsourcing for Anti-Corruption a Handbook of Innovative Legal, Technical, and Policy Proposals and a Guide to Their Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATP World Tour 2019

ATP World Tour 2019 Note: Grand Slams are listed in red and bold text. STARTING DATE TOURNAMENT SURFACE VENUE 31 December Hopman Cup Hard Perth, Australia Qatar Open Hard Doha, Qatar Maharashtra Open Hard Pune, India Brisbane International Hard Brisbane, Australia 7 January Auckland Open Hard Auckland, New Zealand Sydney International Hard Sydney, Australia 14 January Australian Open Hard Melbourne, Australia 28 January Davis Cup First Round Hard - 4 February Open Sud de France Hard Montpellier, France Sofia Open Hard Sofia, Bulgaria Ecuador Open Clay Quito, Ecuador 11 February Rotterdam Open Hard Rotterdam, Netherlands New York Open Hard Uniondale, United States Argentina Open Clay Buenos Aires, Argentina 18 February Rio Open Clay Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Open 13 Hard Marseille, France Delray Beach Open Hard Delray Beach, USA 25 February Dubai Tennis Championships Hard Dubai, UAE Mexican Open Hard Acapulco, Mexico Brasil Open Clay Sao Paulo, Brazil 4 March Indian Wells Masters Hard Indian Wells, United States 18 March Miami Open Hard Miami, USA 1 April Davis Cup Quarterfinals - - 8 April U.S. Men's Clay Court Championships Clay Houston, USA Grand Prix Hassan II Clay Marrakesh, Morocco 15 April Monte-Carlo Masters Clay Monte Carlo, Monaco 22 April Barcelona Open Clay Barcelona, Spain Hungarian Open Clay Budapest, Hungary 29 April Estoril Open Clay Estoril, Portugal Bavarian International Tennis Clay Munich, Germany Championships 6 May Madrid Open Clay Madrid, Spain 13 May Italian Open Clay Rome, Italy 20 May Geneva Open Clay Geneva, Switzerland -

Selling Mexico: Race, Gender, and American Influence in Cancún, 1970-2000

© Copyright by Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 ii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _________________________ Tracy A. Butler APPROVED: _________________________ Thomas F. O’Brien Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ John Mason Hart, Ph.D. _________________________ Susan Kellogg, Ph.D. _________________________ Jason Ruiz, Ph.D. American Studies, University of Notre Dame _________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics iii SELLING MEXICO: RACE, GENDER, AND AMERICAN INFLUENCE IN CANCÚN, 1970-2000 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Tracy A. Butler May, 2016 iv ABSTRACT Selling Mexico highlights the importance of Cancún, Mexico‘s top international tourism resort, in modern Mexican history. It promotes a deeper understanding of Mexico‘s social, economic, and cultural history in the late twentieth century. In particular, this study focuses on the rise of mass middle-class tourism American tourism to Mexico between 1970 and 2000. It closely examines Cancún‘s central role in buttressing Mexico to its status as a regional tourism pioneer in the latter half of the twentieth century. More broadly, it also illuminates Mexico‘s leadership in tourism among countries in the Global South. -

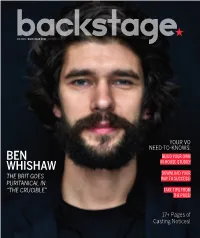

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Government Hearing January 27, 2021

Transcript Prepared by Clerk of the Legislature Transcribers Office Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee January 27, 2021 Rough Draft Does not include written testimony submitted prior to the public hearing per our COVID-19 Response protocol BREWER: Good morning, welcome, welcome to the Government, Military and Veterans Affairs Committee. I am Senator Tom Brewer from Gordon, Nebraska, representing the 43rd Legislative District. I serve as the Chair of this committee. Because of the COVID situation, we're going to go through a number of COVID specific things and then we'll get into the Government Committee intro here. For the safety of our committee members, staff, pages, and the public, we ask those attending our hearing to abide by the following procedures. Due to social distancing requirements, seating in the hearing room is limited, very limited. We ask that you only enter the hearing room when it is necessary for you to attend your hearing. The bills will be taken up as posted outside the hearing on the wall. The list will be updated after each hearing to identify which bill is the current bill up, so the number will be up there and then the pages will then post outside. The committees will pause between each bill to allow enough time for the public to move in and move out. Keep in mind that after each testifier, we'll need a slight delay in order to clean the table, clean the chair. So just understand we'll have some pauses. But those pauses are not for senators to start talking because the mikes will be on and it will still be getting recorded. -

ARO 09/30/04 Complete

Committee Meeting of ASSEMBLY REGULATORY OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE “Discussion on the Department of Human Services, Division of Developmental Disabilities Proposed New Rule, N.J.A.C. 10:42A ‘Life Threatening Emergencies.’ The rules are proposed to implement the requirements of Danielle’s Law.” LOCATION: Committee Room 8 DATE: September 30, 2004 State House Annex 10:00 a.m. Trenton, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COMMITTEE PRESENT: Assemblyman William D. Payne, Chair Assemblyman Joseph Cryan, Vice Chair Assemblyman Douglas H. Fisher Assemblywoman Connie Myers ALSO PRESENT: James F. Vari Wali Abdul-Salaam Nancy S. Fitterer Office of Legislative Services Assembly Majority Assembly Republican Committee Aide Committee Aide Committee Aide Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Theresa C. Wilson Deputy Commissioner Services For People With Disabilities New Jersey Department of Human Services 2 James Evanochko Administrative Practice Officer Division of Developmental Disabilities New Jersey Department of Human Services 15 Senator Thomas H. Kean Jr. District 21 32 Diane Gruskowski Danielle’s Mother, and Member The Family Alliance to Stop Abuse and Neglect 35 Robin M. Turner Danielle’s Aunt, and Member The Family Alliance to Stop Abuse and Neglect 40 Assemblyman Guy R. Gregg District 24 48 Janette R. Vance Member The Family Alliance to Stop Abuse and Neglect 49 Victoria Horrocks Member The Family Alliance to Stop Abuse -

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published Or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures)

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures): “An Unfrozen North”. By J. Madeleine Nash, 19 February 2018, High Country News, https://www.hcn.org/issues/50.3/an-unfrozen-north “Exploding Killer Lakes”. By Taylor Mayol, 2 March 2016, OZY, http://www.ozy.com/flashback/exploding-killer-lakes/65346 “Arctic Sunlight Can Speed Up the Greenhouse Effect”. By Susan Linville, Moments in Science, Posted February 27, 2015. http://indianapublicmedia.org/amomentofscience/arctic-sunlight-speed-greenhouse- effect/ http://ns.umich.edu/new/releases/22338-climate-clues-sunlight-controls-the-fate-of-carbon- released-from-thawing-arctic-permafrost http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2014/aug/science-study-sunlight-not-microbes-key-co2- arctic http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140821141548.htm http://www.aninews.in/newsdetail9/story180338/it-039-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide- in-arctic.html http://www.sciencecodex.com/sunlight_not_microbes_key_to_co2_in_arctic-140097 http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-08/uom-sct081514.php http://phys.org/news/2014-08-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic.html http://www.laboratoryequipment.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-permafrosts-released- carbon http://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/it-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide-in- arctic-114082200579_1.html http://www.eurasiareview.com/22082014-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic/ http://www.rdmag.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-carbon-released-thawing-arctic- permafrost http://zeenews.india.com/news/eco-news/sunlight-not-bacteria-key-to-co2-in-arctic_956515.html -

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R

Center for Hawaiian Sovereignty Studies 46-255 Kahuhipa St. Suite 1205 Kane'ohe, HI 96744 (808) 247-7942 Kenneth R. Conklin, Ph.D. Executive Director e-mail [email protected] Unity, Equality, Aloha for all To: HOUSE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION For hearing Thursday, March 18, 2021 Re: HCR179, HR148 URGING THE SUPERINTENDENT OF EDUCATION TO REQUEST THE BOARD OF EDUCATION TO CHANGE THE NAME OF PRESIDENT WILLIAM MCKINLEY HIGH SCHOOL BACK TO THE SCHOOL'S PREVIOUS NAME OF HONOLULU HIGH SCHOOL AND TO REMOVE THE STATUE OF PRESIDENT MCKINLEY FROM THE SCHOOL PREMISES TESTIMONY IN OPPOSITION There is only one reason why some activists want to abolish "McKinley" from the name of the school and remove his statue from the campus. The reason is, they want to rip the 50th star off the American flag and return Hawaii to its former status as an independent nation. And through this resolution they want to enlist you legislators as collaborators in their treasonous propaganda campaign. The strongest evidence that this is their motive is easy to see in the "whereas" clauses of this resolution and in documents provided by the NEA and the HSTA which are filled with historical falsehoods trashing the alleged U.S. "invasion" and "occupation" of Hawaii; alleged HCR179, HR148 Page !1 of !10 Conklin HSE EDN 031821 suppression of Hawaiian language and culture; and civics curriculum in the early Territorial period. Portraying Native Hawaiians as victims of colonial oppression and/or belligerent military occupation is designed to bolster demands to "give Hawaii back to the Hawaiians", thereby producing a race-supremacist government and turning the other 80% of Hawaii's people into second-class citizens. -

China's Global Quest for Resources and Implications for the United

CHINA’S GLOBAL QUEST FOR RESOURCES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 26, 2012 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2012 i U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION Hon. DENNIS C. SHEA, Chairman Hon. WILLIAM A. REINSCH, Vice Chairman Commissioners: CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW Hon. CARTE GOODWIN DANIEL A. BLUMENTHAL DANIEL M. SLANE ROBIN CLEVELAND MICHAEL R. WESSEL Hon. C. RICHARD D’AMATO LARRY M. WORTZEL, Ph.D . JEFFREY L. FIEDLER MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109-108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. -

THE JESUIT MISSION to CANADA and the FRENCH WARS of RELIGION, 1540-1635 Dissertation P

“POOR SAVAGES AND CHURLISH HERETICS”: THE JESUIT MISSION TO CANADA AND THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION, 1540-1635 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joseph R. Wachtel, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Alan Gallay, Adviser Professor Dale K. Van Kley Professor John L. Brooke Copyright by Joseph R. Wachtel 2013 Abstract My dissertation connects the Jesuit missions in Canada to the global Jesuit missionary project in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries by exploring the impact of French religious politics on the organizing of the first Canadian mission, established at Port Royal, Acadia, in 1611. After the Wars of Religion, Gallican Catholics blamed the Society for the violence between French Catholics and Protestants, portraying Jesuits as underhanded usurpers of royal authority in the name of the Pope—even accusing the priests of advocating regicide. As a result, both Port Royal’s settlers and its proprietor, Jean de Poutrincourt, never trusted the missionaries, and the mission collapsed within two years. After Virginia pirates destroyed Port Royal, Poutrincourt drew upon popular anti- Jesuit stereotypes to blame the Jesuits for conspiring with the English. Father Pierre Biard, one of the missionaries, responded with his 1616 Relation de la Nouvelle France, which described Port Royal’s Indians and narrated the Jesuits’ adventures in North America, but served primarily as a defense of their enterprise. Religio-political infighting profoundly influenced the interaction between Indians and Europeans in the earliest years of Canadian settlement. -

Impact Campaigns, Summarised in Impact Reports Which Are Published on Our Website

@britdoc britdoc.org 2 The Art of Impact. STORIES CAN CONQUER FEAR, YOU KNOW. THEY CAN MAKE BEN OKRI POET THE HEART LARGER. 04 The Art of Impact. The Impact of Art. 05 OUR ABOUT FUNDS OUR BRITDOC p34 p06 FILMS p40 Helping good films be great Engaging new HELLO partners GOOD PITCH p82 IMPACT Sharing our FIELD GUIDE learning p124 We are a nonprofit, founded in 2005, committed to enabling great Building new documentary films and connecting audiences them to audiences. Doing and measuring Based in London and New York, we work with filmmakers and partners globally, reaching IMPACT DOC audiences all over the world. AWARD ACADEMY p118 p94 In this book you can find out SOMETHING more about what we do and IMPACT REAL how it fits into our five DISTRIBUTION p102 interconnected strategic areas. p106 06 The Art of Impact. The Impact of Art. 07 “For many years, BRITDOC has spotted and supported the most urgent projects – OUR MISSION OUR DRIVING PRINCIPLE nurturing them with love, ensuring they make a difference. But gradually We befriend great filmmakers, Great documentaries enrich BRITDOC became more support great films, broker the lives of individuals. They than a fund. It is, by now, new partnerships, build have a unique ability to the forum for our most important conversations new business models, share engage and connect people, in nonfiction cinema.” knowledge and develop transform communities and Joshua Oppenheimer Director audiences globally. improve societies. “ BRITDOC are experts in We aim to lead by example — That’s why we are dedicated collaboration, innovation and rapid prototyping.” innovate, share and be copied, to the Impact of Art, and the Cara Mertes and innovate again. -

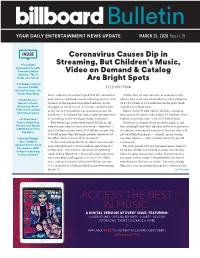

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MARCH 25, 2020 Page 1 of 28 INSIDE Coronavirus Causes Dip in • Paradigm’s Streaming, But Children’s Music, Coronavirus Layoffs Panned by Music Video on Demand & Catalog Industry: ‘This Is Really Just Greed’ Are Bright Spots • LA Clippers Owner Reaches $400M BY ED CHRISTMAN Deal to Purchase The Forum From MSG Music industry executives hoped that the coronavirus Within that, all sales formats, as summarized by • Radio Stations quarantines might buoy music streaming activity with albums plus track equivalent albums, fell a whopping Adjust to Social- so much of the population isolated indoors. So far, 25.6% last week to 1.94 million from the prior week Distancing, Work- the opposite has occurred. In the last two full weeks total of 2.61 million units. From-Home Studios as the Covid-19 pandemic was spreading across the Before Covid-19 took hold in the U.S., streaming Amid Coronavirus world, the U.S. industry has had a moderate downturn was soaring: the week ending March 5 marked 2020’s • As Dow Jones in streaming, with even bigger drops in physical. highest streaming week, with 25.55 billion plays. Scores Single-Day Two weeks ago, in the week ended March 12, the But there is a bigger cloud on the horizon: as mil- Record, Live Nation industry saw a dip in music streaming — down by 1% lions of people lose their jobs due to the vast economic & MSG Stocks Post to 25.3 billion streams from 25.55 billion streams. But shutdowns, some music executives fear that they will Big Gains it would appear that the longer people stayed out of get rid of fixed expenses —- namely, music stream- • Spotify Pledges the office, the less music they consumed. -

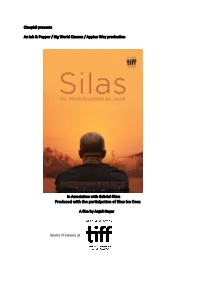

Produced with the Participation of Blue Ice Docs

Cinephil presents An Ink & Pepper / Big World Cinema / Appian Way production In Association with Gabriel Films Produced with the participation of Blue Ice Docs A film by Anjali Nayar World Premiere at 80 minutes English, Liberian English • • Canada/South Africa/Kenya 2017 • Contacts at TIFF: Producer: Producer: Steven Markovitz Anjali Nayar Big World Cinema Ink & Pepper Productions E: [email protected] E: T: +27 83 2611 044 T: +1- 415-910-4625 Sales Agent: Publicist: Philippa Kowarsky Charlene Coy Cinephil C2C Communications E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: +972 3 566 4129 T: +1-416-451-1471 Tagline: No more business as usual Logline With a network of dedicated citizen reporters by his side, seasoned Liberian activist Silas Siakor challenges the corrupt and nepotistic status quo in his fight for local communities. Synopsis Liberian activist, Silas Siakor is a tireless crusader, fighting to crush corruption and environmental destruction in the country he loves. Through the focus on one country, Silas is a global tale that