Film Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Padis Opeda Ballet

FREDERICK WISEMAN BIOGRAPHY Frederick Wiseman is an American filmmaker, born on January 1969, Hospital in 1970, Juvenile Court in 1973 and Welfare 1st, 1930, in Boston, Massachusetts. A documentary filmmaker, in 1975. In addition to Zoo (1993), he directed three other most of his films paint a portrait of leading North American documentaries on our relationship with the animal world: Primate institutions. in 1974, Meat in 1976 and Racetrack in 1985 respectively about After studying law he started teaching the subject without any real scientific experiments on animals, the mass production of beef interest. In decided he should work at something he liked and had cattle destined for the slaughterhouse and consumers and the the idea to make a movie of Warren Miller’s novel, The Cool World. Belmont racetrack one of the major American racetracks. Since at that point he had no film experience he asked Shirley He began an examination of the consumer society with Model in Clarke to direct the film. ProducingThe Cool World demystified the 1980 and The Store in 1983. The sharpness of his gaze, his biting film making process for him and he decided to direct, produce and humour and his compassion characterize his exploration of the edit his own films. Three years later came the theatrical release of model agency and the big store Neiman Marcus, temples of western his first documentary,Titicut Follies, an uncompromising look at a modernity. In 1995, he slipped into the wings of the theatre and prison for the criminally insane. directed La Comédie-Française ou l’amour joué. -

Dvd- Gesamtverzeichnis

34 / FILM, FERNSEHEN, HÖRFUNK DVD- GESAMTVERZEICHNIS STAND: NOVEMBER 2014 WWW.GOETHE.DE/FILMKATALOG GESAMTVERZEICHNIS ALLER AUF DVD ERSCHIENENEN FILME Alle hier verlinkten Filme stehen In ausführlicher Form im Goethe-Institut Filmkatalog unter www.goethe.de/filmkatalog Die DVD ist für DAAD-Lektoren und Ortslektoren über das Goethe-Institut bestellbar (Frau Heidrun Lange, [email protected]) zum Verbleib im Lektorat bestellbar, unter Wahrung von Lizenzzeiten und Sperrgebieten. bestellbar Der Film ist nicht einzeln, sondern nur als Gesamtpaket mit xx DVDs Paket mit xx DVDs erhältlich. nur Ausleihe DVD ist nur über die regionalen Filmarchive ausleihbar. Sofern ein regionales Filmarchiv die DVD erworben hat, so ist diese über nur Ausleihe, wenn vom GIA das Filmarchiv selbst ausleihbar – Informationen dazu, ob eine dieser so erworben gekennzeichneten DVDs vorliegt, stehen im Goethe-Institut Filmkatalog unter www.goethe.de/filmkatalog Wichtige Anmerkung Wichtige, zu beachtende Anmerkung in der Spalte STATUS. Kursiv markierte Titel stehen nicht zur Verfügung wegen abgelaufenen nicht zur Verfügung Lizenzrechten. TITEL FILMPAKET/FILMREIHE IN-NR. STATUS 10 Fragen an die Demokratie Demokratie für alle? IN 3570 nur Ausleihe 14 Diaries of the GREAT WAR (14 Tagebücher 1. Weltkrieg IN 3889 nur Ausleihe des Ersten Weltkriegs) 20. Juli, Der Artur Brauner Filmreihe IN 3684 bestellbar 4 Tage im Mai IN 3717 bestellbar Lotte Reiniger Edition Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed, Die IN 1112 nur Ausleihe Kinderfilm Abschied - Brechts letzter Sommer Jan Schütte IN 1690 bestellbar Alexander Kluge Edition Abschied von der sicheren Seite des Lebens IN 2915 nur Ausleihe Edition Filmmuseum Nr. 29 Alexander Kluge Edition Abschied von gestern IN 1045 nur Ausleihe Edition Filmmuseum Nr. -

The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3

2008 The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3 Grantees 13 Fiscal Sponsorships 28 Financial Highlights 30 Trustees and Staff 33 Committees 34 www.seattlefoundation.org | (206) 622-2294 While the 2008 financial crisis created greater needs in our community, it also gave us reason for hope. 2008 Foundation donors have risen to the challenges that face King County today by generously supporting the organizations effectively working to improve the well-being of our community. The Seattle Foundation’s commitment to building a healthy community for all King County residents remains as strong as ever. In 2008, with our donors, we granted more than $63 million to over 2000 organizations and promising initiatives in King County and beyond. Though our assets declined like most investments nationwide, The Seattle Foundation’s portfolio performed well when benchmarked against comparable endowments. In the longer term, The Seattle Foundation has outperformed portfolios comprised of traditional stocks and bonds due to prudent and responsible stewardship of charitable funds that has been the basis of our investment strategy for decades. The Seattle Foundation is also leading efforts to respond to increasing need in our community. Late last year The Seattle Foundation joined forces with the United Way of King County and other local funders to create the Building Resilience Fund—a three-year, $6 million effort to help local people who have been hardest hit by the economic downturn. Through this fund, we are bolstering the capacity of selected nonprofits to meet increasing basic needs and providing a network of services to put people on the road on self-reliance. -

Press Release a Tribute To... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One

Press Release A Tribute to... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One of Europe’s Most Versatile Directors August 24, 2012 This year’s A Tribute to... award goes to author, director and producer Tom Tykwer. This is the first time that a German filmmaker has ever received one of the Zurich Film Festival’s honorary awards. Tykwer will collect his award in person during the Award Night at the Zurich Opera House. The ZFF will screen his most important films in a retrospective held at the Filmpodium. The ZFF is delighted that one of Europe’s most versatile directors is coming to Zurich. “Tom Tykwer has ensured that German film has once more gained in renown, significance and innovation, both on a national and international level,” said the festival management. Born 1965 in Wuppertal, Tom Tykwer shot his first feature DEADLY MARIA in 1993. He founded the X Filme Creative Pool in 1994 together with Stefan Arndt and the directors Wolfgang Becker and Dani Levy. It is currently one of Germany’s most successful production and distribution companies. RUN LOLA RUN Tykwer’s second cinema feature WINTER SLEEPERS (1997) was screened in competition at the Locarno Film Festival. RUN LOLA RUN followed in 1998, with Franka Potente and Moritz Bleibtreu finding themselves as the protagonists in a huge international success. The film won numerous awards, including the Deutscher Filmpreis in Gold for best directing. Next came THE PRINCESS AND THE WARRIOR (2000), also with Frank Potente, followed by Tykwer’s fist English language production HEAVEN (2002), which is based on a screenplay by the Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski and stars Cate Blanchett and Giovanni Ribisi. -

Declaration Under Section 4 (4) of the Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable System) Regulation, 2017 (No

Version 1.0/2019 Declaration Under Section 4 (4) of The Telecommunication (Broadcasting and Cable) Services Interconnection (Addressable System) Regulation, 2017 (No. 1 of 2017) 4(4)a: Target Market Distribution Network Location States/Parts of State covered as "Coverage Area" Bangalore Karnataka Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Delhi Delhi; Haryana; Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh Hyderabad Telangana Kolkata Odisha; West Bengal; Sikkim Mumbai Maharashtra 4(4)b: Total Channel carrying capacity Distribution Network Location Capacity in SD Terms Bangalore 506 Bhopal 358 Delhi 384 Hyderabad 456 Kolkata 472 Mumbai 447 Kindly Note: 1. Local Channels considered as 1 SD; 2. Consideration in SD Terms is clarified as 1 SD = 1 SD; 1 HD = 2 SD; 3. Number of channels will vary within the area serviced by a distribution network location depending upon available Bandwidth capacity. 4(4)c: List of channels available on network List attached below in Annexure I 4(4)d: Number of channels which signals of television channels have been requested by the distributor from broadcasters and the interconnection agreements signed Nil Page 1 of 37 Version 1.0/2019 4(4)e: Spare channels capacity available on the network for the purpose of carrying signals of television channels Distribution Network Location Spare Channel Capacity in SD Terms Bangalore Nil Bhopal Nil Delhi Nil Hyderabad Nil Kolkata Nil Mumbai Nil 4(4)f: List of channels, in chronological order, for which requests have been received from broadcasters for distribution of their channels, the interconnection agreements -

Marcus Lamb, Founder and President of Daystar Television Network

Marcus Lamb, Founder and President of Daystar Television Network Marcus Lamb, founder and president of Daystar Television Network, was born October 7, 1957 in Cordele, Georgia and raised in Macon, Georgia. At the age of 15, in the summer of 1973, he began preaching as an evangelist. Upon skipping his senior year of high school in 1974, at the age of 16, Marcus enrolled in Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee on a full scholarship. At age 19, he began his final senior semester at the private liberal arts school and graduated Magna Cum Laude. In December of 1981, Marcus Lamb founded Word of God Fellowship in Macon. He married Joni Trammell of Greenville, South Carolina in 1982, and she began to travel full time with him as they ministered in more than 20 states. As an evangelist, Marcus quoted so many scriptures in his sermons that many began referring to him as the “Walking Bible.” While on a trip to Israel in 1983, God spoke to Marcus Lamb and told him to found a Christian television station in Montgomery, Alabama. In 1985, Marcus built WMCF-TV, “45 Alive,” in Montgomery. It was the first Christian TV station in the state, and Marcus was the youngest person in the country to build a full power television station. In 1990, the Lambs moved to Dallas, Texas, to build KMPX-TV 29. Through a series of miracles and divine favor, TV 29 went on the air full power in September of 1993. Daystar Television Network officially launched in 1997 with a live broadcast of T.D. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

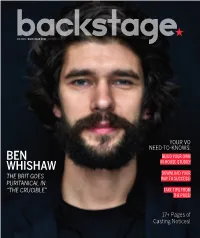

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Frederick Wiseman

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 15 | 2017 Lolita at 60 / Staging American Bodies Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.10953 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean, « Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » », Miranda [En ligne], 15 | 2017, mis en ligne le 04 octobre 2017, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/10953 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda. 10953 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. provided by OpenEdition View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » 1 Compte-rendu de Journée d’étude : Frederick Wiseman, « Ordre et résistance » Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, Cinémathèque de Toulouse, 19 mai 2017 /Organisée par Zachary Baqué (CAS) et Vincent Souladié (PLH) Youri Borg et Damien Sarroméjean 1 Organisée par les laboratoires CAS et PLH, en association avec la Cinémathèque de Toulouse, cette journée d’étude consacrée à Frederick Wiseman se propose d’aborder l’œuvre dense d’un cinéaste américain majeur du genre documentaire, reconnu tant par la critique que par ses pairs, mais dont les films (Titicut Follies (1967), Primate (1974) et Public Housing (1997) pour citer les plus connus) sont paradoxalement peu vus. -

Soul Boy Seite 1 Von 15

12/10 Film des Monats: Soul Boy Seite 1 von 15 Ausgabe Dezember 2010: Soul Boy (Kinostart: 02.12.2010) Filmbesprechung Soul Boy Interview "Es hat uns alle irgendwie verändert" Hintergrund FilmAfrica! Hintergrund Junge Lebenswelten im subsaharischen Kino Anregungen für den Unterricht Arbeitsblatt 12/10 Film des Monats: Soul Boy Seite 2 von 15 Soul Boy Deutschland, Kenia 2010 Drama Kinostart: 02.12.2010 Verleih: X Verleih AG Regie: Hawa Essuman Drehbuch: Billy Kahora Darsteller/innen: Samson Odhiambo, Leila Dayan Opollo, Krysteen Savane, Frank Kimani, Joab Ogolla, Lucy Gachanja u. a. Kamera: Christian Almesberger Laufzeit: 60 min, dt.F. Format: 35mm/Digital, Farbe, Cinemascope Filmpreise: International Film Festival Rotterdam: Dioraphte Audience Award; Kalasha Film and TV Awards 2010: Bester Kurzfilm, Bester Hauptdarsteller (Samson Odhiambo), Drehbuch (Billy Kahora); Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin 2010 (Sektion Generation/Kplus) FSK: ab 6 J. FBW-Prädikat: Besonders Wertvoll Altersempfehlung: ab 10 J. Klassenstufen: ab 5. Klasse Themen: Afrika, Erwachsenwerden, Coming of Age, Tradition, Mythos Unterrichtsfächer: Deutsch, Religion, Erdkunde/Geografie, Kunst, Ethik Eine Seele retten Matt und müde kauert der Vater des 14-jährigen Abila auf dem Boden im Hinterraum seines kleinen Geschäfts. Nicht zum ersten Mal sieht der Junge seinen Vater in einem solchen Zustand. Doch dieses Mal ist es anders – ernster. Man habe ihm seine Seele geraubt, stammelt der Vater. Keinen Augenblick zögert Abila und rennt los. Hinaus in den Slum Kibera, den größten in der kenianischen Hauptstadt Nairobi, um die Seele seines Vaters zu retten. Abila rennt Dass diese Szene in ihrer Dynamik an Lola rennt (Deutschland 1998) von Tom Tykwer erinnert, ist kein Zufall, denn der deutsche Regisseur war maßgeblich an der Produktion von Soul Boy beteiligt. -

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published Or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures)

Scientific Outreach by George Kling (Published or Broadcast Interviews; Reports; Lectures): “An Unfrozen North”. By J. Madeleine Nash, 19 February 2018, High Country News, https://www.hcn.org/issues/50.3/an-unfrozen-north “Exploding Killer Lakes”. By Taylor Mayol, 2 March 2016, OZY, http://www.ozy.com/flashback/exploding-killer-lakes/65346 “Arctic Sunlight Can Speed Up the Greenhouse Effect”. By Susan Linville, Moments in Science, Posted February 27, 2015. http://indianapublicmedia.org/amomentofscience/arctic-sunlight-speed-greenhouse- effect/ http://ns.umich.edu/new/releases/22338-climate-clues-sunlight-controls-the-fate-of-carbon- released-from-thawing-arctic-permafrost http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2014/aug/science-study-sunlight-not-microbes-key-co2- arctic http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140821141548.htm http://www.aninews.in/newsdetail9/story180338/it-039-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide- in-arctic.html http://www.sciencecodex.com/sunlight_not_microbes_key_to_co2_in_arctic-140097 http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-08/uom-sct081514.php http://phys.org/news/2014-08-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic.html http://www.laboratoryequipment.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-permafrosts-released- carbon http://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/it-s-sunlight-that-controls-carbon-dioxide-in- arctic-114082200579_1.html http://www.eurasiareview.com/22082014-sunlight-microbes-key-co2-arctic/ http://www.rdmag.com/news/2014/08/sunlight-controls-fate-carbon-released-thawing-arctic- permafrost http://zeenews.india.com/news/eco-news/sunlight-not-bacteria-key-to-co2-in-arctic_956515.html -

Ch Cago School 27Th Annual

2010 School Group &Schedule 27th Annual Ch cago International Children’s Film Festival October 22–October 29 773–281–9075 [email protected] www.facets.org/kids Locations Dear Educators, W Belle Plaine Ave W Belle Plaine Ave Are you looking for an affordable field trip that will make a real impact on your students’ learning? ve N Clybour e A ve e Av e Av Av rt A d ve o n What better way to inspire and captivate young minds than through the magic of movies? p A e a l e n e t h S Ellis E 58th St. ve h A Av v u Av ve s A o N A acine R N M o S r N A N ilw N Lavergne e N University N Leclaire a oodlawn c uke i th Ave ve W Fullerton C Ave e of Chicago S Kimbark W Fullerton yler Ave S W r Ave N Laporte W Cu Av ve e W Cuyl A Join us for the 27 annual Chicago International Children’s Film Festival (CICFF) and use the power of e N A E 59th St. E 59th St. N Clybour W Irving Park Rd Midway Plaisance media to engage and entertain your students while enhancing your classroom work. As the largest and W Irving Park Rd e v Ave ve A N Greenview A Midway Plaisance e n ve longest running children’s film festival in North America, the CICFF discovers the best in world cinema, n A rg A e E 60th St.