4486 Steedman.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) � Vol

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR LAW REPORTING LIBRARY' THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII—No. 154 NAIROBI, 14th August, 2020 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GALETT'E'NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES CONTD' PAGE The Auctioneers Act—Appointment 3160 The Co-operative Societies Act—Inquiry Order 3206 Supreme Court of Kenya —AugustRecess 3160 The Environmental Management and Co-ordination Act— Environmental Impact Assessment Study Reports 3206-3208 The Senate Standing Orders—Special Sitting of the Senate 3160 Disposal of Uncollected Goods 3208-3209 The Nairobi International Financial Centre Act— Appointment 3160 Loss of Share Certificate 3210 The Wildlife Conservation and Management Act—Task Change of Names 3210-3211 Force 3160-3161 County Governments Notices 3161-3162 SUPPLEMENT Nos. 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 139, 140 and 141 The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, etc 3162-3178 Legislative Supplements, 2020 The Public Officer Ethics Act—Administrative Procedures 3178-3182 LEGAL NOTICE NO. PAGE The Energy Act—Amended Schedule of Tariffs for Supply 135-138—The Public Health (Covid-19 Prohibition of Electrical Energy, etc 3182-3184 cif Sale of Alcoholic Drinks) Rules, 2020, etc .. 1715 The Kenya Information and Communications Act— 139—The Tax Procedures (Unassembled Motor Application for Licences 3184 Vehicles and Trailers) (Amendment) Regulations, 2020 1739 The Unclaimed Financial Assets Act—No Objection 3185 140-150—The Competition Act—Exclusions 1741 The Estate Agents Act—Registered Estate Agents 3186 151-132—The Stamp Duty (Valuation of The National Government Constituencies Development Immovable Property) Regulations, 2020, etc .. -

Press Release a Tribute To... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One

Press Release A Tribute to... Award to German Director Tom Tykwer One of Europe’s Most Versatile Directors August 24, 2012 This year’s A Tribute to... award goes to author, director and producer Tom Tykwer. This is the first time that a German filmmaker has ever received one of the Zurich Film Festival’s honorary awards. Tykwer will collect his award in person during the Award Night at the Zurich Opera House. The ZFF will screen his most important films in a retrospective held at the Filmpodium. The ZFF is delighted that one of Europe’s most versatile directors is coming to Zurich. “Tom Tykwer has ensured that German film has once more gained in renown, significance and innovation, both on a national and international level,” said the festival management. Born 1965 in Wuppertal, Tom Tykwer shot his first feature DEADLY MARIA in 1993. He founded the X Filme Creative Pool in 1994 together with Stefan Arndt and the directors Wolfgang Becker and Dani Levy. It is currently one of Germany’s most successful production and distribution companies. RUN LOLA RUN Tykwer’s second cinema feature WINTER SLEEPERS (1997) was screened in competition at the Locarno Film Festival. RUN LOLA RUN followed in 1998, with Franka Potente and Moritz Bleibtreu finding themselves as the protagonists in a huge international success. The film won numerous awards, including the Deutscher Filmpreis in Gold for best directing. Next came THE PRINCESS AND THE WARRIOR (2000), also with Frank Potente, followed by Tykwer’s fist English language production HEAVEN (2002), which is based on a screenplay by the Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski and stars Cate Blanchett and Giovanni Ribisi. -

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’S 2017 Elections

“Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH “Not Worth the Risk” Threats to Free Expression Ahead of Kenya’s 2017 Elections Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34761 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa is an independent not-for profit organization that promotes freedom of expression and access to information as a fundamental human right as well as an empowerment right. ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa was registered in Kenya in 2007 as an affiliate of ARTICLE 19 international. ARTICLE 19 Eastern African has over the past 10 years implemented projects that included policy and legislative advocacy on media and access to information laws and review of public service media policies and regulations. The organization has also implemented capacity building programmes for journalists on safety and protection and for a select civil society organisation to engage with United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU) mechanisms in 14 countries in Eastern Africa. -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

The State of Artistic Freedom 2021

THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2021 1 Freemuse (freemuse.org) is an independent international non-governmental organisation advocating for freedom of artistic expression and cultural diversity. Freemuse has United Nations Special Consultative Status to the Economic and Social Council (UN-ECOSOC) and Consultative Status with UNESCO. Freemuse operates within an international human rights and legal framework which upholds the principles of accountability, participation, equality, non-discrimination and cultural diversity. We document violations of artistic freedom and leverage evidence-based advocacy at international, regional and national levels for better protection of all people, including those at risk. We promote safe and enabling environments for artistic creativity and recognise the value that art and culture bring to society. Working with artists, art and cultural organisations, activists and partners in the global south and north, we campaign for and support individual artists with a focus on artists targeted for their gender, race or sexual orientation. We initiate, grow and support locally owned networks of artists and cultural workers so their voices can be heard and their capacity to monitor and defend artistic freedom is strengthened. ©2021 Freemuse. All rights reserved. Design and illustration: KOPA Graphic Design Studio Author: Freemuse Freemuse thanks those who spoke to us for this report, especially the artists who took risks to take part in this research. We also thank everyone who stands up for the human right to artistic freedom. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of February 2021. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

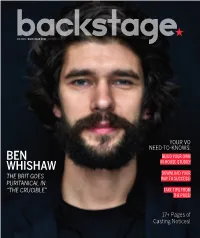

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

CHEROTICH MUNG'ou.Pdf

THE ROLE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN PEACEBUILDING IN MOUNT ELGON REGION, KENYA BY CHEROTICH MUNG’OU A Thesis submitted to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research, in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies of Kabarak University June, 2016 DECLARATION PAGE Declaration I hereby declare that this research thesis is my own original work and to the best of my knowledge has not been presented for the award of a degree in any university or college. Student’s Signature: Student’s Name: Cherotich Mung’ou Registration No: GDE/M/1265/09/11 Date: 30thJune, 2016 i RECOMMENDATION PAGE To the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research: The thesis entitled “The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Peacebuilding in Mt Elgon Region, Kenya” and written by Cherotich Mung’ou is presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research of Kabarak University. We have reviewed the thesis and recommend it be accepted in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies. 24th June, 2016 Dr. Tom Kwanya Senior Lecturer, The Technical University of Kenya 30th June, 2016 ____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Osodo Lecturer, Maseno University ii Acknowledgement I am greatly indebted to various individuals for the great roles they played throughout my research undertaking. Most importantly, I thank God for the far He has brought me. My first gratitude goes to my supervisors Dr Tom Kwanya and Dr Joseph Osodo for their tireless effort in reviewing my work. I appreciate your intellectual advice and patience. -

Evolution of Sheng During the Last Decade

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 49 | 2014 Varia Evolution of Sheng during the Last Decade Aurélia Ferrari Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/340 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2014 Number of pages: 29-54 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Aurélia Ferrari, « Evolution of Sheng during the Last Decade », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 49 | 2014, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/340 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est Evolution of Sheng during the Last Decade Aurélia Ferrari Introduction Sheng, popularly deined as an acronym for “Swahili-English slang” (Mazrui, 1995), emerged in the 1960s in the multicultural environment of Nairobi. It is an urban language which combines mainly Kiswahili and English but also other Kenyan languages such as Kikuyu, Luyha, Dholuo and Kikamba. Sheng is characterized by an important linguistic lexibility. It does not have an oficial status even if it widelyis spoken, especially by the youth. Originally used as a vehicular language between people from different regions, it is becoming a vernacular language, some people born in the 1980s or later having Sheng as their irst language. Sheng is not a unique linguistic phenomenon in Africa. In the last ifty years, urbanization and globalization have prompted the emergence of new urban linguistic codes. Such codes are based on multilingual speech and characterized by unstable vocabulary. -

The Influence of Internal and External Factors Affecting the Kenya Film Industry

THE INFLUENCE OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL FACTORS AFFECTING THE KENYA FILM INDUSTRY BY ESTHER N. NGUMA UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY-AFRICA SUMMER, 2015 THE INFLUENCE OF INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL FACTORS AFFECTING THE KENYA FILM INDUSTRY BY ESTHER N. NGUMA A Project Report Submitted to the Chandaria School of Business in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters in Business Administration (MBA) UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY-AFRICA SUMMER, 2015 STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this project is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college, institution or university other than the United States International University in Nairobi for academic credit. Signed: _________________________________ Date: _____________________ Esther Nguma (Student ID: 639858) This proposal has been presented for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor. Signed: _________________________________ Date: _____________________ Dr. George Achoki Signed: _________________________________ Date: _____________________ Dean, Chandaria School of Business ii COPYRIGHT All rights reserved. No part of this research project may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author. ©Copyright Esther N. Nguma, 2015 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I acknowledge my Supervisor, Dr. George Achoki for his continued guidance and intellectual support throughout the undertaking of this research, may God bless him immeasurably. I also owe an appreciation to the various Film producers of the 30 Film Production Houses that granted me the permission to collect data. I am grateful to my father – Humphrey Nguma and mother - Lucy Nguma for being my backbone during the process. -

Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Ga㯠Ramaka's Karmen Geã¯

The "Monumental" Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Gaï Ramaka's Karmen Geï Anjali Prabhu Cinema Journal, Volume 51, Number 4, Summer 2012, pp. 66-86 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press DOI: 10.1353/cj.2012.0088 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cj/summary/v051/51.4.prabhu.html Access Provided by Wellesley College Library at 11/10/12 7:18PM GMT The “Monumental” Heroine: Female Agency in Joseph Gaï Ramaka’s Karmen Geï by ANJALI PRABHU Abstract: Karmen Geï presents itself as a feminist African fi lm with a scandalously revolu- tionary central character. These aspects of the fi lm are reconsidered by focusing attention on the totality of its form, and by studying the politics of monumentalizing the heroine. he Senegalese fi lmmaker Joseph Gaï Ramaka’s chosen mode for representing his heroine in the fi lm Karmen Geï (2001) is that of the “monumental.” This has several consequences for the heroine’s possibilities within the diegesis. For example, the entire mise-en-scène makes the monumental heroine imperme- able to interpretation and resistant to critical discourses. This invites further evalua- Ttion of the fi lm’s political meanings, which have been much touted by critics. Critics and the fi lmmaker himself tend to agree on the fi lm’s political valence, primarily because of its unconventional, revolutionary heroine, and particularly because the fi lm is identifi ed as specifi cally African. My argument is twofold. First, I argue that Karmen Geï proposes what I am calling a monumental (and therefore an impossible) version of female identity and therefore also eschews many moments of plausible feminine agency. -

Cine-Ethiopia: the History and Politics of Film in the Horn of Africa Published by Michigan University Press DOI: 10.14321/J.Ctv1fxmf1

This is the version of the chapter accepted for publication in Cine-Ethiopia: The History and Politics of Film in the Horn of Africa published by Michigan University Press DOI: 10.14321/j.ctv1fxmf1 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32029 CINE-ETHIOPIA THE HISTORY AND POLITICS OF FILM IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Edited by Michael W. Thomas, Alessandro Jedlowski & Aboneh Ashagrie Table of contents INTRODUCTION Introducing the Context and Specificities of Film History in the Horn of Africa, Alessandro Jedlowski, Michael W. Thomas & Aboneh Ashagrie CHAPTER 1 From የሰይጣን ቤት (Yeseytan Bet – “Devil’s House”) to 7D: Mapping Cinema’s Multidimensional Manifestations in Ethiopia from its Inception to Contemporary Developments, Michael W. Thomas CHAPTER 2 Fascist Imperial Cinema: An Account of Imaginary Places, Giuseppe Fidotta CHAPTER 3 The Revolution has been Televised: Fact, Fiction and Spectacle in the 1970s and 80s, Kate Cowcher CHAPTER 4 “The dead speaking to the living”: Religio-cultural Symbolisms in the Amharic Films of Haile Gerima, Tekletsadik Belachew CHAPTER 5 Whether to Laugh or to Cry? Explorations of Genre in Amharic Fiction Feature Films, Michael W. Thomas 2 CHAPTER 6 Women’s Participation in Ethiopian Cinema, Eyerusalem Kassahun CHAPTER 7 The New Frontiers of Ethiopian Television Industry: TV Serials and Sitcoms, Bitania Taddesse CHAPTER 8 Migration in Ethiopian Films, at Home and Abroad, Alessandro Jedlowski CHAPTER 9 A Wide People with a Small Screen: Oromo Cinema at Home and in Diaspora, Teferi Nigussie Tafa and Steven W. Thomas CHAPTER 10 Eritrean Films between Forced Migration and Desire of Elsewhere, Osvaldo Costantini and Aurora Massa CHAPTER 11 Somali Cinema: A Brief History between Italian Colonization, Diaspora and the New Idea of Nation, Daniele Comberiati INTERVIEWS Debebe Eshetu (actor and director), interviewed by Aboneh Ashagrie Behailu Wassie (scriptwriter and director), interviewed by Michael W.