Human Rights in Guatemala During President De Leon Carpio's First Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfil Departamental De El Quiché

Código PR-GI- 006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental El Quiché Fecha de Emisión 24/03/17 Página 1 de 27 ESCUDO Y BANDERA MUNICIPAL DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE EL QUICHE Departamento de El Quiché Código PR-GI-006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental Fecha de El Quiché Emisión 24/03/17 Página 2 de 27 1. Localización El departamento de El Quiché se encuentra situado en la región VII o región sur-occidente, la cabecera departamental es Santa Cruz del Quiché, limita al norte con México; al sur con los departamentos de Chimaltenango y Sololá; al este con los departamentos de Alta Verapaz y Baja Verapaz; y al oeste con los departamentos de Totonicapán y Huehuetenango. Se ubica en la latitud 15° 02' 12" y longitud 91° 07' 00", y cuenta con una extensión territorial de 8,378 kilómetros cuadrados, 15.33% de Valle, 84.67% de Montaña más de 17 nacimientos abastecen de agua para servicio domiciliar. Por la configuración geográfica que es bastante variada, sus alturas oscilan entre los 2,310 y 1,196 metros sobre el nivel del mar, por consiguiente los climas son muy variables, en los que predomina el frío y el templado. 2. Geografía El departamento de El Quiché está bañado por muchos ríos. Entre los principales sobresalen el río Chino o río Negro (que recorre los municipios de Sacapulas, Cunén, San Andrés Sajcabajá, Uspantán y Canillá, y posee la represa hidroeléctrica Chixoy); el río Blanco y el Pajarito (en Sacapulas); el río Azul y el río Los Encuentros (en Uspantán); el río Sibacá y el Cacabaj (en Chinique); y el río Grande o Motagua en Chiché. -

Indigenous Maya Knowledge and the Possibility of Decolonizing Education in Guatemala

Indigenous Maya Knowledge and the Possibility of Decolonizing Education in Guatemala by Vivian Michelle Jiménez Estrada A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Vivian Michelle Jiménez Estrada 2012 Indigenous Maya Knowledge and the Possibility of Decolonizing Education in Guatemala Vivian Michelle Jiménez Estrada Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Maya peoples in Guatemala continue to practice their Indigenous knowledge in spite of the violence experienced since the Spanish invasion in 1524. From 1991 until 1996, the state and civil society signed a series of Peace Accords that promised to better meet the needs of the Maya, Xinka, Garífuna and non-Indigenous groups living there. In this context, how does the current educational system meet the varied needs of these groups? My research investigates the philosophy and praxis of Maya Indigenous knowledge (MIK) in broadly defined educational contexts through the stories of 17 diverse Maya professional women and men involved in educational reform that currently live and work in Guatemala City. How do they reclaim and apply their ancestral knowledge daily? What possible applications of MIK can transform society? The findings reveal that MIK promotes social change and healing within and outside institutionalized educational spaces and argues that academia needs to make room for Indigenous theorizing mainly in areas of education, gender, knowledge production, and nation building. I analyze these areas from anticolonial and critical Indigenous standpoints from which gender and Indigenous identities weave through the text. -

1413 PPM Santa María Nebaj

1 2 Contenido Presentación ................................................................................................................. 5 Introducción .................................................................................................................. 7 Capítulo I. Marco legal e institucional ....................................................................... 10 1.1. Marco legal ............................................................................................................. 10 1.2. Marco de política pública ........................................................................................ 11 1.3. Marco institucional .................................................................................................. 12 Capítulo II. Marco de referencia ................................................................................. 13 2.1. Ubicación geográfica .............................................................................................. 13 2.2. Delimitación y división administrativa ...................................................................... 14 2.3. Proyección poblacional ........................................................................................... 15 2.4. Educación ............................................................................................................... 16 2.5. Salud ...................................................................................................................... 16 2.6. Sector seguridad y justicia ..................................................................................... -

Download File

A War of Proper Names: The Politics of Naming, Indigenous Insurrection, and Genocidal Violence During Guatemala’s Civil War. Juan Carlos Mazariegos Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Juan Carlos Mazariegos All Rights Reserved Abstract A War of Proper Names: The Politics of Naming, Indigenous Insurrection, and Genocidal Violence During Guatemala’s Civil War During the Guatemalan civil war (1962-1996), different forms of anonymity enabled members of the organizations of the social movement, revolutionary militants, and guerrilla combatants to address the popular classes and rural majorities, against the backdrop of generalized militarization and state repression. Pseudonyms and anonymous collective action, likewise, acquired political centrality for revolutionary politics against a state that sustained and was symbolically co-constituted by forms of proper naming that signify class and racial position, patriarchy, and ethnic difference. Between 1979 and 1981, at the highest peak of mass mobilizations and insurgent military actions, the symbolic constitution of the Guatemalan state was radically challenged and contested. From the perspective of the state’s elites and military high command, that situation was perceived as one of crisis; and between 1981 and 1983, it led to a relatively brief period of massacres against indigenous communities of the central and western highlands, where the guerrillas had been operating since 1973. Despite its long duration, by 1983 the fate of the civil war was sealed with massive violence. Although others have recognized, albeit marginally, the relevance of the politics of naming during Guatemala’s civil war, few have paid attention to the relationship between the state’s symbolic structure of signification and desire, its historical formation, and the dynamics of anonymous collective action and revolutionary pseudonymity during the war. -

ZAP GUATEMALA END of YEAR REPORT JANUARY 1, 2018 – DECEMBER 31, 2018 Recommended Citation: Zika AIRS Project (ZAP)

The Zika AIRS (ZAP) Project Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS 2) Task Order Six ZAP GUATEMALA END OF YEAR REPORT JANUARY 1, 2018 – DECEMBER 31, 2018 Recommended Citation: Zika AIRS Project (ZAP). February 2019. ZAP Guatemala End of Year Report 2018. Rockville, MD. Abt Associates Inc. Contract No.: GHN-I-00-09-00013-00 Task Order: AID-OAA-TO-14-00035 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development Submitted: February 14, 2019 Abt Associates Inc. 1 6130 Executive Boulevard 1 Rockville, Maryland 20852 1 T. 301.347.5000 1 F. 301.913.9061 1 www.abtassociates.com ZAP GUATEMALA END OF YEAR REPORT JANUARY 1, 2018 – DECEMBER 31, 2018 The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 3 CONTENTS Contents Acronyms ii 1. Executive Summary ...............................................................................................................1 2. Progress and Outcomes.........................................................................................................2 2.1 Community Mobilization, Social and Behavior Change Communication .................. 2 2.2 Vector Control .............................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1 Larviciding and Source Reduction...................................................................................................3 2.2.2 IRS………… ......................................................................................................................................5 -

Guatemala Project

PEACE BRIGADES INTERNATIONAL – GUATEMALA PROJECT MIP - MONTHLY INFORMATION PACKAGE – GUATEMALA Number 98, November 2011 1. NOTES ON THE CURRENT SITUATION 2. ACTIVITIES OF PBI GUATEMALA: WITHIN GUATEMALA 2.1 MEETINGS WITH GUATEMALAN AUTHORITIES, DIPLOMATIC CORPS AND INTERNATIONAL ENTITIES 2.2 MEETINGS WITH CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS 2.3 ACCOMPANIMENT 2.4 FOLLOW-UP 2.5 OBSERVATION 3. ACTIVITIES OF PBI GUATEMALA – OUTSIDE GUATEMALA 4. NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS 1. NOTES ON THE CURRENT SITUATION IMPUNITY The Convergence for Human Rights condemns an attempt to give immunity to military personnel accused of genocide Guatemala, 24.11.2011 (CA, SV) .- The Convergence for Human Rights denounced the attempt to pass a bill that favors military personnel accused of crimes against humanity, so that they cannot be judged by the Guatemalan courts. The independent MP Christian Bousinott presented under pretext of national urgency, the 37-11 Initiative, which according to Iduvina Hernandez, director of the Association for the Study and Promotion of Democratic Security (SEDEM) had already been passed by Congress in its second reading in 2008. However, when comparing the initiative now submitted, which was shelved for three years, Hector Nuila, Nineth Montenegro and Aníbal García-members of Congress, realized the phrase "with the exception of crimes considered against humanity " had been removed. They were forced to withdraw from the Chamber, to break quorum and prevent final approval of the document. Julio Solórzano Foppa, the son of one of the victims of internal armed conflict, said: "This was a deceitful and illegal act. They intended for us to believe that these falsified documents were the ones approved in 2008." Oswaldo Samayoa, human rights activist, said an investigation has begun to criminally prosecute those who collaborated in the falsification and manipulation of the draft. -

Best Practices for Working with Interpreters

VERA NETWORK RESOURCE BEST PRACTICES FOR WORKING WITH INTERPRETERS Vera Institute of Justice ● Unaccompanied Children Program ● October 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Guidance for Working with Interpreters .............................................................................................2 What is Interpreting? ................................................................................................................................ 2 Assessing the Child’s Language Proficiency .............................................................................................. 2 The Benefits of Having Bilingual Staff ....................................................................................................... 2 Deciding on the Mode of Interpretation: Telephonic or In-Person? ........................................................ 3 Before the Session .................................................................................................................................... 3 During the Session .................................................................................................................................... 4 After the Session ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Appendix A: Indigenous Languages Spoken in Central America ............................................................6 -

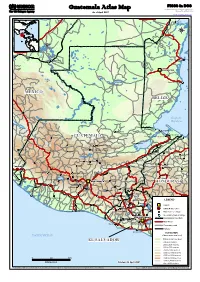

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

Plan De Desarrollo Municipal

P N S Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo del Municipio de Zacualpa, Quiché y 02.01.02 Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia, Dirección de CM Planificación Territorial. Plan de Desarrollo Zacualpa, Quiché 1404 Guatemala: SEGEPLAN/DPT, 2010. 96 p. il. ; 27 cm. Anexos. (Serie: PDM SEGEPLAN, CM 1404) 1. Municipio. 2. Diagnóstico municipal. 3. Desarrollo local. 4. Planificación territorial. 5. Planificación del desarrollo. 6. Objetivos de desarrollo del milenio. P Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo Municipio Zacualpa, Quiché, Guatemala, Centro América PBX: 77366224 Email: [email protected] Secretaría de Planificación y Programación Nde la Presidencia 9ª. calle, 10-44 zona 1, Guatemala, Centro América PBX: 23326212 www.segeplan.gob.gt Se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este documento, siempre que no se alteren los contenidos ni los créditos de autoría y edición S Directorio Ernesto Calachij Riz Presidente del Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo Zacualpa, Quiché Karin Slowing Umaña Secretaria de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia, SEGEPLAN Ana Patricia Monge Cabrera Sub Secretaria de Planificación y Ordenamiento Territorial, SEGEPLAN Juan Jacobo Dardón Sosa Asesor en Planificación y Metodología, SEGEPLAN Werner Wotzbelí Villar Anleu Delegado Departamental, SEGEPLAN, Quiché. P Equipo facilitador del proceso Rolando Gutiérrez Gutiérrez Director Municipal de Planificación Zacualpa, Quiché Ricardo Pineda León Facilitador del proceso de planificación, SEGEPLAN, Quiché N Filiberto Guzmán C. Especialista -

How Local Institutions Emerge from Civil War Regina Bateson Assistant Professor

How Local Institutions Emerge from Civil War Regina Bateson Assistant Professor Department of Political Science MIT Oct. 2, 2015 The field research for this paper was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, Yale University, and the Tinker Foundation. I gratefully acknowledge research support from tHe Universidad del Valle de Guatemala wHile in tHe field. At MIT, Meghan O’Dell provided superb research assistance. Please send comments and questions to [email protected] . ABSTRACT: Civil wars are typically understood as destructive, leaving poor economic performance, damaged pHysical infrastructure, and reduced Human capital in their wake. But civil wars are also constructive, producing new local institutions that can persist into the postwar period. In this paper, I use qualitative evidence from Guatemala to demonstrate tHat even tHe most devastating conflicts can spawn durable local institutions. Specifically, I focus on the civil patrols, which were government-sponsored local militias during tHe Guatemalan civil war. AltHougH tHe Peace Accords of 1996 required tHe civil patrols to demobilize, I sHow tHat more nearly 20 years later, tHey are still patrolling, functioning as security patrols in tHeir communities today. After considering alternative explanations, I use Historical documents and ricH, etHnograpHic evidence to draw causal links between tHe wartime civil patrols and tHe present-day security patrols. These findings begin to fill a gaping hole in the literature on the civil wars, whicH—until now—has largely ignored the local institutional consequences of conflict. _________________________________________________________________________________________________ The study of civil wars is riven with intractable debates. When, where, and why are civil wars most likely (e.g. -

Resumen) CORREDOR ECONÓMICO

DIAGNÓSTICO (resumen) CORREDOR ECONÓMICO Quetzaltenango-Totonicapán-Quiché para el Proyecto Creando Oportunidades Económicas MARZO 2019 MAR // 2019 Este documento fue producido por el Proyecto Creando Oportunidades Económicas 72052018C000001 para revisión de la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional. Preparado por: Evelyn Córdova y equipo multidisciplinario de consultores Página 1 de 15 Contenido Aspectos generales del Corredor Económico ....................................................................................................... 2 Índice de Competitividad Local ............................................................................................................................. 3 Sector Productivo .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Talento Humano .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Empleo .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Migración y Remesas .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Gobernanza para la competitividad y la inversión ............................................................................................... 11 Problemática y -

Schooling in Chajul: National Struggles, Community Voices

Schooling in Chajul: National Struggles, Community Voices Lindsey Musen Kate Percuoco February 2010 This report was requested by Limitless Horizons Ixil. © 2010 Lindsey Musen and Kate Percuoco. Please contact the authors at [email protected] with questions or for permission to reproduce. [SCHOOLING IN CHAJUL] February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Purpose 1 Chajul and the Ixil Region 2 Methodology 2 Education in Guatemala 3 Enrollment & Demographics 3 History of Education Policy 4 Current Education Policy 6 Gender 7 Poverty 9 Language and Culture 11 Academic Barriers 12 Education in Chajul 13 Funding 15 Politics 16 Enrollment and Class Size 17 Attendance, Grade Repetition, & Dropout 18 Gender 19 Facilities and Supplies 19 Materials 20 Technology 21 Curriculum & Instruction 21 Teachers 24 Family 25 Health 25 Outlying Communities 26 Social Services in Chajul 27 Strengths and Opportunities 29 Educational Needs 29 Models of Education Programming 30 Recommendations 34 Limitations 39 Authors and Acknowledgements 39 References 40 Appendix A: Limitless Horizons Ixil 43 PURPOSE This study was requested by Limitless Horizons Ixil1 (LHI), a non-governmental organization (NGO) operating in San Gaspar Chajul in the western highlands of Guatemala. The research is meant to illuminate the challenges faced by students, teachers, and educational leaders in the community, so that LHI 1 For more information about LHI, please visit http://www.limitlesshorizonsixil.org. 1 [SCHOOLING IN CHAJUL] February 2010 and other organizations in Chajul can focus their resources towards the greatest needs, while integrating community members into the process. CHAJUL AND THE IXIL REGION San Gaspar Chajul is isolated by beautiful mountains and has maintained its rich Ixil Mayan traditions and language.