Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlements and Natural Resource Systems Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfil Departamental De Huehuetenango

Código PR-GI-006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental Fecha de Huehuetenango Emisión 24/03/17 Página 1 de 30 ESCUDO Y BANDERA MUNICIPAL DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE HUEHUETENANGO Código PR-GI- 006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental Fecha Huehuetenango de 24/03/17 Emisión Página 2 de 30 Departamento de Huehuetenango Municipios # Nombre 1 Huehuetenango 2 Chiantla 3 Malacatancito 4 Aguacatán 5 Santa Bárbara 6 San Sebastián Huehuetenango 7 San Juan Atitán 8 San Rafael Petzal 9 San Gaspar Ixchil 10 Colotenango 11 Santiago Chimaltenango 12 Todos Santos Cuchumatán 13 San Juan Ixcoy 14 San Pedro Soloma 15 Santa Eulalia 16 Santa Cruz Barillas 17 San Mateo Ixtatán 18 San Sebastián Coatán 19 San Rafael La Independencia 20 Nentón 21 San Miguel Acatán 22 Concepción Huista 23 Jacaltenango 24 Santa Ana Huista 25 San Antonio Huista 26 La Democracia 27 San Pedro Necta 28 La Libertad 29 San Idelfonso Ixtahuacán 30 Cuilco 31 Tectitán 32 Unión Cantinil (nuevo) 33 Petatán (nuevo) Fuente: Municipalidad de Huehuetenango. Código PR-GI- 006 Versión 01 Perfil Departamental Fecha Huehuetenango de 24/03/17 Emisión Página 3 de 30 1. Localización El departamento de Huehuetenango, está situado en la región Nor-occidental del país y limita al norte y oeste, con México, al sur con los departamentos de San Marcos, Quetzaltenango y Totonicapán; y al este con el departamento de Quiché. Se encuentra a una distancia de aproximadamente 264 km de la ciudad capital. Con una superficie de 7,400 K². Huehuetenango se ubica en el noroccidente del país y pertenece a la Región VII. Limita al norte y al oeste con la república de México, al sur con San Marcos y al este con Quiché. -

No. DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO

HUEHUETENANGO No. DEPARTAMENTO MUNICIPIO NOMBRE_ESTABLECIMIENTO DIRECCION LUGAR TELEFONO NIVEL SECTOR CANTON TRES CRUCES ALDEA 1 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXA A EORM EL MANZANILLO PARVULOS OFICIAL CASERIO LOS POZOS, ALDEA 2 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN COPB ANEXO A EORM PICHIQUIL 50068156 PREPRIMARIA BILINGUE OFICIAL 3 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXA A EORM CASERIO EL ROSARIO ALDEA TUIXCOX PARVULOS OFICIAL NUCLEO FAMILIAR EDUCATIVO PARA EL 4 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN DESARROLLO NUFED POR AUTOGESTION ALDEA CRUZ CHEX BASICO OFICIAL CASERIO LOS POZOS, ALDEA 5 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EORM PICHIQUIL 50068156 PRIMARIA OFICIAL NUCLEO FAMILIAR EDUCATIVO PARA EL 6 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN DESARROLLO -NUFED- ALDEA CANTZELA BASICO OFICIAL 7 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN COLEGIO PRIVADO 'EL NUEVO MILLENIUM' 3A. AVENIDA 3-01 ZONA 1 77237684 DIVERSIFICADO PRIVADO 8 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXA A EORM CANTON LOS ALISOS ALDEA EL MANZANILLO PARVULOS OFICIAL 9 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXA A EORM 'JUAN DIEGUEZ OLAVERRI' ALDEA LA BARRANCA PARVULOS OFICIAL 10 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN IEBC DE ENSEÑANZA 'DOMINGO SAVIO' ALDEA PICHIQUIL BASICO COOPERATIVA IEBC DE ENSEÑANZA 'INTERCULTURAL 11 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN CHALCHITEKO ALDEA RIO SAN JUAN BASICO COOPERATIVA 12 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN IEBC DE ENSEÑANZA ALDEA CLIMENTORO BASICO COOPERATIVA 13 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN COLEGIO PRIVADO MIXTO MAYA AGUACATECO 3A. CALLE 7-42 ZONA 1 77660095 BASICO PRIVADO 14 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP 9A. CALLE A 13-21 ZONA 5 7649816 4970423 PARVULOS OFICIAL 15 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN INEB 3A. AVENIDA 3-01 ZONA 1 77660102 BASICO OFICIAL 16 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXO A EORM ALDEA EL POTRERILLO PARVULOS OFICIAL INSTITUTO GUATEMALTECO DE EDUCACION 17 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN RADIOFONICA (IGER) AGUACATAN DIVERSIFICADO PRIVADO 18 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EODP ANEXA A EORM ALDEA EL RANCHO PARVULOS OFICIAL 19 HUEHUETENANGO AGUACATAN EORM CASERIO JOYA GRANDE ALDEA EL SUJ PRIMARIA OFICIAL ESCUELA TECNICA BILINGUE AGRICOLA DE EDUC. -

Huehuetenango

DERECHOS MINEROS DEPARTAMENTO DE HUEHUETENANGO ID NOMBRE REGISTRO AREA_Km2 TIPO TITULAR FECHA_INICIO MUNICIPIOS DEPARTAMENTO (S) 1 LA CANADA II MT-0625 0.3000 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. 23/06/1925 SAN SEBASTIAN HUEHUETENANGO HUEHUETENANGO 2 NANNIE CF-1504 0.2400 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. 01/10/1906 CHIANTLA HUEHUETENANGO 3 LA SEVERA CT-104 0.2500 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. 18/05/1906 CHIANTLA HUEHUETENANGO 4 LA QUEBRADILLA CF-1902 0.0800 EXPLOTACION TEODORO RECINOS 25/10/1908 CHIANTLA HUEHUETENANGO DOMINGO Y ENRIQUE OVALLE Y JOSE Y 5 SANTO DOMINGO MT-2809 0.3000 EXPLOTACION JULIAN AGUIERRE 30/09/1909 JACALTENANGO HUEHUETENANGO INDUSTRIALES SANTORINI, SOCIEDAD 6 ATACAMA LEXT-509 1.0000 EXPLOTACION ANONIMA 20/10/2004 SANTIAGO CHIMALTENANGO HUEHUETENANGO 7 EL SACRAMENTO LEXT-207 2.0607 EXPLOTACION JUAN MARCO ANTONIO DIAZ ALVA 02/06/1999 NENTON HUEHUETENANGO 8 ASTURICA LEXT-155 0.0525 EXPLOTACION HIGINIO RODRIGUEZ 22/01/1999 AGUACATAN HUEHUETENANGO 9 LOS ALISOS LEXT-037 0.1450 EXPLOTACION HIGINIO RODRIGUEZ 30/11/2001 CHIANTLA Y HUEHUETENANGO HUEHUETENANGO MINA SANTA ELENA 10 (SUSPENDIDA) CT-101 1.0000 EXPLOTACION MINERA QUETZAL, S.A. 11/11/1995 SAN SEBASTIAN HUEHUETENANGO HUEHUETENANGO 11 LOS LIRIOS CT-005 0.1000 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. 10/05/1994 SAN IDELFONSO IXTAHUACAN HUEHUETENANGO 12 CLAVITO IV CT-008 0.1000 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. 16/06/1961 SAN IDELFONSO IXTAHUACAN HUEHUETENANGO COOPERATIVA DE PRODUCCION 13 TORLON CT-148 0.1600 EXPLOTACION INDUSTRIAL JUVENTUD MINERA 28/06/1901 SAN SEBASTIAN HUEHUETENANGO HUEHUETENANGO 14 SANTA RITA MT-0322 0.3000 EXPLOTACION RECINOS E HIJOS 09/08/1922 SAN JUAN ATITAN HUEHUETENANGO 15 LA PROVIDENCIA ET-056 4.4900 EXPLOTACION JOSEFINA GRANADOS VIUDA DE TELLO 18/05/1978 NENTON HUEHUETENANGO SAN IDELFONSO IXTAHUACAN Y 16 ANABELLA CT-007 2.4545 EXPLOTACION MINAS DE GUATEMALA, S.A. -

Increasing Access to Family Planning Among Indigenous Groups in Guatemala

INCREASING ACCESS TO FAMILY PLANNING AMONG INDIGENOUS GROUPS IN GUATEMALA DECEMBER 2008 This publication was produced for review by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by Sara Netzer and Liz Mallas of the Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1. The USAID | Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1, is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Contract No. GPO-I-01-05-00040-00, beginning September 30, 2005. Task Order 1 is implemented by Futures Group International, in collaboration with the Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA), White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood (WRA), Futures Institute, and Religions for Peace. INCREASING ACCESS TO FAMILY PLANNING AMONG INDIGENOUS GROUPS IN GUATEMALA DECEMBER 2008 The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................iv Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................v Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................vii I. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 -

Isheries Surney

ISHERIES SURNEY JUAGULTURE WED AQUACULTURES WON 0 0 0 0 LAKE IZABAL FISHERIES SURVEY INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR AQUACULTURE DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND ALLIED AQUACULTURES AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION AUBURN UNIVERSITY AUBURN, ALABAMA 36830 Project: AID/cs'd-2-780 Date: September 5, 1973 LAKE JZABAL FISHERIES SURVEY by W.D. Davies Auburn University Auburn, Alabama 36830 Project: AID/csd-2780 Date of Survey: June 11 - 22, 1973 Date: September 5, 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 ITINERARY .............................................. 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................... 2 2.1 Guatemalan Geography and Population ............... 3 2.2 Fish Marketing and Consumption .................... 4 2.3 Government Division Responsible for Fisheries 6 2.4 Lake Izabal, El Golfete and the Rio Dulce Water Resources. ...................................... 7 3.0 THE FISHERIES ........................................... 8 3.1 Lake and River Fisheries ........................... 8 3.2 Fishing Regulations ................................ 10 3.3 Assessment of the Fishery .......................... 10 4.0 RECREATIONAL USE OF LAKE IZABAL, RIO DULCE AND EL GOLFETE......................................... 11 5.0 SUMMARY OF SURVEY AND PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS .. 12 5.1 Summary ....................... ................... 12 5.2 Recommended Scope of Work ........................ 13 5.3 Program Requirements .............................. 15 6.0 CONFERENCES ............................................ 17 7.0 LITERATURE CITED ..................................... -

Rosalío Teleguario Magzul

Rosalío Teleguario Magzul Proceso Histórico del Desarrollo Educativo y Humano de la población del Área Norte de Huehuetenango: San Pedro Soloma, San Juan Ixcoy, Santa Eulalia y San Sebastián Coatán. Asesora: M.A. Epifania Leticia Urízar Urízar Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Facultad de Humanidades Escuela de Estudios de Postgrado Maestría en Educación para el Desarrollo Guatemala, febrero de 2012. Este informe fue presentado por el autor como trabajo de tesis previo optar al grado de Maestro en Educación para el Desarrollo. Guatemala, febrero de 2012. INDICE RESUMEN I INTRODUCCION IV CAPITULO I CONSIDERACIONES FUNDAMENTALES SOBRE LA EDUCACIÓN Y EL DESARROLLO 1 1.1 Educación 1 1.1.1 Tipos de educación 3 1.2 Desarrollo 6 1.2.1 Desarrollo económico 9 1.2.2 Desarrollo social 10 1.2.3 Desarrollo human 12 1.3 La educación para el desarrollo 13 1.4 Pobreza 14 1.5 Capital humano 15 CAPITULO II CARACTERIZACIÓN TERRITORIAL, ETNICA, POLITICA Y ECONOMICA DEL AREA NORTE DE HUEHETENANGO 18 2.1. Territorio 18 2.1.1 San Juan Ixcoy 19 2.1.2 San Pedro Soloma 22 2.1.3 Santa Eulalia 25 2.1.4 San Sebastián Coatán 28 2.1.5 Configuración étnica de los municipios de San Juan Ixcoy, San Pedro Soloma, Santa Eulalia y San Sebastián Coatán. 31 2.2 Antecedentes históricos de los municipios de San Juan Ixcoy, San Pedro Soloma, Santa Eulalia y San Sebastián Coatán. 33 2.3 Organización social de los municipios de San Juan Ixcoy, San Pedro Soloma, Santa Eulalia y San Sebastián Coatán. -

Plan De Desarrollo Municipal

P N S 02.01.02 Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo del Municipio de Concepción Huista. Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia. Dirección de CM Planificación Territorial. Plan de Desarrollo Concepción Huista, 1322 Huehuetenango. Guatemala: SEGEPLAN/DPT, 2010. 109 p. il. ; 27 cm. Anexos. (Serie: PDM SEGEPLAN, CM 1322) 1. Municipio. 2. Diagnóstico municipal. 3. Desarrollo local. 4. Planificación territorial. 5. Planificación del desarrollo. 6. Objetivos de desarrollo del milenio. P Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo Municipio de Concepción Huista, Huehuetenango, Guatemala, Centro América PBX: 77830266 http://cpdmuniconcepcionhuista.blogspot.com Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia 9ª. calle, 10-44 zona 1, Guatemala, Centro América PBX: 23326212 www.segeplan.gob.gt N Se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este documento, siempre que no se alteren los contenidos ni los créditos de autoría y edición S Directorio Pascual López Escobar Presidente del Consejo Municipal de Desarrollo, Concepción Huista, Huehuetenango Karin Slowing Umaña Secretaria de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia, SEGEPLAN Ana Patricia Monge Cabrera Sub Secretaria de Planificación y Ordenamiento Territorial, SEGEPLAN Juan Jacobo Dardón Sosa Asesor en Planificación y Metodología, SEGEPLAN Luis Arturo Meza Ochoa Delegado Departamental, SEGEPLAN, Huehuetenango P Equipo facilitador del proceso Mynor Guadalupe Alva Saucedo Director Municipal de Planificación, Concepción Huista, Huehuetenango Carlos Adalberto Macario Ajcá -

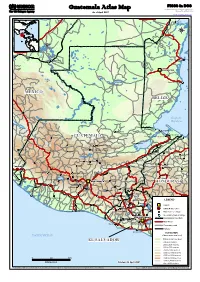

Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected]

FICSS in DOS Guatemala Atlas Map Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services As of April 2007 Email : [email protected] ((( Corozal Guatemala_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Balancan !! !! !! !! Tenosique Belize City !! BELMOPANBELMOPAN Stann Creek Town !! MEXICOMEXICO BELIZEBELIZE !! Golfo de Honduras San Juan ((( !! Lívingston !! El Achiotal !! Puerto Barrios GUATEMALAGUATEMALA Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ((( ((( ((( Soloma ((( Cuyamel Cobán ((( El Estor ((( ((( Chajul ((( !! ((( San Pedro Carchá ((( Morales !! Motozintla Huehuetenango !! San Cristóbal Verapaz ((( Cunen ((( ((( !! Macuelizo ((( ((( Los Amates((( Petoa ((( Cubulco Salamá Trinidad ((( ((( !! Gualán ((( !! !! ((( !! ((( San Sebastián ((( San Jerónimo ((( Jesus Maria La Agua ((( !! Rabinal ((( Protección ((( Joyabaj TapachulaTapachula Totonicapán ((( Zacapa !! Naranjito ((( ((( !! Tapachula ((( ((( Santa Bárbara ((( Quezaltenango !! Dulce Nombre ((( !! San José Poaquil !! Chiquimula !! !! Sololá !! Santa Rosa !! Comalapa ((( Patzún !! Santiago Atitlán !! Tecun Uman !! Chimaltenango GUATEMALAGUATEMALA !! Jalapa HONDURASHONDURAS Mazatenango HONDURASHONDURAS Antigua ((( !! Esquipulas !! !! Retalhuleu ((( !! ((( Ciudad Vieja ((( Monjas Alotenango ((( Nueva Ocotepeque !! ((( Santa Catarina Mita Amatitlán ((( ((( Patulul ((( Ayarza Río Bravo ((( ((( Metapán !! !! Escuintla ((( !! ((( !! Jutiapa((( ((( !! Champerico ((( !! Cuilapa !! Asunción Mita ((( Yamarang Pueblo Nuevo Tiquisate ((( Erandique Yupiltepeque ((( ((( Atescatempa Nueva Concepción LEGEND -

Nexos Locales Project Quarterly Report

ooka ;’l/ NEXOS LOCALES PROJECT QUARTERLY REPORT #16 April – June 2018 CONTRACT No. AID-520-C-14-00002 July 20, 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development.Page 1 It of was 103 prepared by DAI Global, LLC. NEXOS LOCALES PROJECT QUARTERLY REPORT #16 April - June 2018 Project Title: Nexos Locales Project Sponsoring USAID office: USAID/Guatemala Contract Number: AID-520-C-14-00002 COR: Claudia Agreda Contractor: DAI Global, LLC. Date of Publication: July 20, 2018 The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ________________________________________________________ 1 SUMMARY OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PHOTOGRAPHS _______________________________ 2 ACRONYMS _________________________________________________________________ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________________________ 6 INTRODUCTION _____________________________________________________________ 8 I. HIGH LEVEL RESULTS______________________________________________________ 10 II. SUMMARY OF KEY ACHIEVEMENTS __________________________________________11 III. OBSTACLES FACED AND LESSONS LEARNED __________________________________13 IV. QUARTERLY PROGRESS RESULTS ___________________________________________14 RESULT 1: _____________________________________________________________14 RESULT 2: _____________________________________________________________ -

Yupiltepeque Amen Aza Por Deslizamien Tos 575000.000000 580000.000000 89°48'W 89°45'W

CODIGO: AMENAZA POR DESLIZAMIENTOS E INUNDACIONES 2206 DEPARTAMENTO DE JUTIAPA 8 MUNICIPIO DE YUPILTEPEQUE AMEN AZA POR DESLIZAMIEN TOS 575000.000000 580000.000000 89°48'W 89°45'W " Quebrada La pred ic c ión d e esta a m ena za utiliza la m eto d o lo gía rec o no c id a " Seca Cerro Pena d e Mo ra -V a hrso n, pa ra estim a r la s a m ena za s d e d esliza m iento s a o Del Garrobo Quebrada El Limón n " Buena er un nivel d e d eta lle d e 1 kilóm etro . Esta c o m pleja m o d ela c ión utiliza 0 p 0 0 a Los 0 0 Vista 0 0 " h 0 una c o m b ina c ión d e d a to s so b re la lito lo gía , la hum ed a d d el suelo , 0 Silva 0 0 C 0 . " . 0 Río 0 0 0 pend iente y pro nóstic o s d e tiem po en este c a so prec ipita c ión 0 "El Cujito 0 6 Quebra 6 d Tamarindo N 7 a gua 7 Las A F " ' a c um ula d a que CATHALAC genera d ia ria m ente a tra vés d el 5 5 N r s 5 ' í Quebrada po 1 a Los Sa 1 1 5 Pilas ° 1 " m o d elo m eso sc a le PSU /N CAR, el MM5. -

Ministerio De Salud Pública Y Asistencia Social Chiquimula

MINISTERIO DE SALUD PÚBLICA Y ASISTENCIA SOCIAL Artículo 10, Numeral 2. Dirección y Teléfonos CHIQUIMULA Dirección Área de Salud, de Chiquimula 8a. Ave. 1-66 zona 1 Chiquimula Teléfono: 79329600 HOSPITAL TELÉFONO DIRECCIÓN Hospital Nacional de Chiquimula 7931-5555 2da. Calle 14-71 Zona1. Chiquimula CATALOGADO COMO DISTRITO DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO Centro de Salud Tipo B Chiquimula 2da. Calle entre 14 y 15 Avenida 14-71 Zona 1 79422107 Puesto de Salud Maraxco Chiquimula En el Centro de Maraxco, Frente a Escuela Ocial Rural Primaria 79422107 Centro Comunitario Pinalito Chiquimula Camino Para el Cimarron, por la torre, aldea El Pinalito 79422107 Centro Comunitario Conacaste Chiquimula Primer Callejon a mano izquierda de la aldea El Conacaste 79422107 Centro Comunitario Shusho Arriba Chiquimula Calle Principal de la aldea Shusho Arriba 79422107 Centro Comunitario Ingeniero Chiquimula A un costado del campo de Futbol de la aldea el Ingeniero 79422107 Centro Comunitario Santa Barbara Chiquimula En el Centro de la aldea Santa Barbara 79422107 Centro Comunitario San Miguel Chiquimula Entrada principal de la aldea San Miguel 79422107 Centro Comunitario Palmarcito Chiquimula A un costado de la Escuela Ocial de la aldea El Palmarcito 79422107 Puesto de Salud El Morral Chiquimula Calle Principal de la aldea El Morral 79422107 Puesto de Salud Vado Hondo Chiquimula Carretera a Jocotan, despues del Puente Shutaque Vado Hondo 79422107 Centro Comunitario Hacienda el Santo Chiquimula Calle Principal de la aldea Hacienda el Santo 79422107 Centyro Comuntiario -

Eta Y Iota En Guatemala

Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala México Belice Petén Huehuetenango Guatemala Quiché Alta Verapaz Izabal Baja Verapaz San Marcos Zacapa Quetzaltenango Chiquimula Honduras Guatemala Sololá Suchitepéquez Jutiapa Escuintla El Salvador Nicaragua Gracias por su interés en esta publicación de la CEPAL Publicaciones de la CEPAL Si desea recibir información oportuna sobre nuestros productos editoriales y actividades, le invitamos a registrarse. Podrá definir sus áreas de interés y acceder a nuestros productos en otros formatos. www.cepal.org/es/publications Publicaciones www.cepal.org/apps Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala Este documento fue coordinado por Omar D. Bello, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Oficina de la Secretaría de la Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), y Leda Peralta, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Comercio Internacional e Industria de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México, en el marco de las actividades del Programa Ordinario de Cooperación Técnica implementado por la CEPAL. Fue preparado por Álvaro Monett, Asesor Regional en Gestión de Información Geoespacial de la División de Estadísticas de la CEPAL, y Juan Carlos Rivas y Jesús López, Oficiales de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Desarrollo Económico de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México. Participaron en su elaboración los siguientes consultores de la CEPAL: Raffaella Anilio, Horacio Castellaro, Carlos Espiga, Adrián Flores, Hugo Hernández, Francisco Ibarra, Sebastián Moya, María Eugenia Rodríguez y Santiago Salvador, así como los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID): Ginés Suárez, Omar Samayoa y Renato Vargas, y los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Mundial: Osmar Velasco, Ivonne Jaimes, Doris Souza, Juan Carlos Cárdenas y Mariano González.