Landmines in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemiological Week 45 (Week Ending 12Th November, 2017)

Early Warning Disease Surveillance and Response Bulletin, Somalia 2017 Epidemiological week 45 (Week ending 12th November, 2017) Highlights Cumulative figures as of week 45 Reports were received from 226 out of 265 reporting 1,363,590 total facilities (85.2%) in week 45, a decrease in the reporting consultations completeness compared to 251 (94.7%) in week 44. 78,596 cumulative cases of Total number of consultations increased from 69091 in week 44 to 71206 in week 45 AWD/cholera in 2017 The highest number of consultations in week 44were for 1,159 cumulative deaths other acute diarrhoeas (2,229 cases), influenza like illness of AWD/Cholera in 2017 (21,00 cases) followed by severe acute respiratory illness 55 districts in 19 regions (834 cases) reported AWD/Cholera AWD cases increased from 77 in week 44 to 170 in week 45 cases No AWD/cholera deaths reported in all districts in the past 7 20794 weeks cumulative cases of The number of measles cases increased from in 323 in week suspected measles cases 44 to 358 in week 45 Disease Week 44 Week 45 Cumulative cases (Wk 1 – 45) Total consultations 69367 71206 1363590 Influenza Like Illness 2287 1801 50517 Other Acute Diarrhoeas 2240 2234 60798 Severe Acute Respiratory Illness 890 911 16581 suspected measles [1] 323 358 20436 Confirmed Malaria 269 289 11581 Acute Watery Diarrhoea [2] 77 170 78596 Bloody diarrhea 73 32 1983 Whooping Cough 56 60 687 Diphtheria 8 11 221 Suspected Meningitis 2 2 225 Acute Jaundice 0 4 166 Neonatal Tetanus 0 2 173 Viral Haemorrhagic Fever 0 0 130 [1] Source of data is CSR, [2] Source of data is Somalia Weekly Epi/POL Updates The number of EWARN sites reporting decrease from 251 in week 44 to 226 in week 45. -

Bay Bakool Rural Baseline Analysis Report

Technical Series Report No VI. !" May 20, 2009 Livelihood Baseline Analysis Bay and Bakool Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia Box 1230, Village Market Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-4000000 Fax: 254-20-4000555 Website: www.fsnau.org Email: [email protected] Technical and Funding Agencies Managerial Support European Commission FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 19 ii Issued May 20, 2009 Acknowledgements These assessments would not have been possible without funding from the European Commission (EC) and the US Office of Foreign Disaster and Assistance (OFDA). FSNAU would like to also thank FEWS NET for their funding contributions and technical support made by Mohamed Yusuf Aw-Dahir, the FEWS NET Representative to Soma- lia, and Sidow Ibrahim Addow, FEWS NET Market and Trade Advisor. Special thanks are to WFP Wajid Office who provided office facilities and venue for planning and analysis workshops prior to, and after fieldwork. FSNAU would also like to extend special thanks to the local authorities and community leaders at both district and village levels who made these studies possible. Special thanks also to Wajid District Commission who was giving support for this assessment. The fieldwork and analysis would not have been possible without the leading baseline expertise and work of the two FSNAU Senior Livelihood Analysts and the FSNAU Livelihoods Baseline Team consisting of 9 analysts, who collected and analyzed the field data and who continue to work and deliver high quality outputs under very difficult conditions in Somalia. This team was led by FSNAU Lead Livelihood Baseline Livelihood Analyst, Abdi Hussein Roble, and Assistant Lead Livelihoods Baseline Analyst, Abdulaziz Moalin Aden, and the team of FSNAU Field Analysts and Consultants included, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Abdirahaman Mohamed Yusuf, Abdikarim Mohamud Aden, Nur Moalim Ahmed, Yusuf Warsame Mire, Abdulkadir Mohamed Ahmed, Abdulkadir Mo- hamed Egal and Addo Aden Magan. -

Afmadow District Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia

Afmadow district Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia Introduction Location map The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was triggered in the perspectives of different groups were captured2. KI coordination with the Camp Coordination and Camp responses were aggregated for each site. These were then Management (CCCM) Cluster in order to provide the aggregated further to the district level, with each site having humanitarian community with up-to-date information on an equal weight. Data analysis was done by thematic location of internally displaced person (IDP) sites, the sectors, that is, protection, water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and capacity of the sites and the humanitarian (WASH), shelter, displacement, food security, health and needs of the residents. The first round of the DSA took nutrition, education and communication. place from October 2017 to March 2018 assessing a total of 1,843 sites in 48 districts. The second round of the DSA This factsheet presents a summary of profiles of assessed sites3 in Afmadow District along with needs and priorities of took place from 1 September 2018 to 31 January 2019 IDPs residing in these sites. As the data is captured through assessing a total of 1778 sites in 57 districts. KIs, findings should be considered indicative rather than A grid pattern approach1 was used to identify all IDP generalisable. sites in a specific area. In each identified site, two key Number of assessed sites: 14 informants (KIs) were interviewed: the site manager or community leader and a women’s representative, to ensure Assessed IDP sites in Afmadow4 Coordinates: Lat. 0.6, Long. -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017. -

Issued January 14 2004 HIGHLIGHTS

Issued January 14 2004 HIGHLIGHTS · Sool Plateau Update : Rains of low intensity and limited spatial coverage fell in the first week of December but did little to alleviate the current humanitarian crisis in Sool Plateau. Nutritional status surveys reflect the deteriorating food security situation of residents. An acute malnutrition rate of 18.9% (W/H<2 z-score or oedema) was found during the first round of Sool Plateau sentinel site surveil- lance exercise in November/December 2003. A UNICEF led mission in mid-December 2003 also recorded an equally high malnutri- tion rate in Sool Plateau of Sanaag (4,841 children screened). The rate was significantly higher in Sool Plateau of Sool Region (2,049 children were screened). Civil insecurity in the area is now threatening to disrupt humanitarian relief operations in the region. · Drought in Hawd of Todgheer : An inter-agency rapid assessment led by the FSAU found that the poor and lower levles of the middle wealth pastoral group are facing a high risk of food shortage, largely as a result of poor Gu 2003 and failed Deyr 2003 rains. Affected households will need to be closely monitored during the harsh, dry Jilaal season. For more information on the drought stricken region, see page 2. · Galgadud Region : UN-OCHA Somalia and FSAU carried out a low level mission to Galagdud (13-20 December 2003) to districts where people had been displaced following civil insecurity in the region. This diplacement, combined with a two month delay in the onset of the Deyr rains has undermined agricultural and livestock activities, increasing the risk of food insecurity. -

1 Project Name UN Joint Programme on Local Governance And

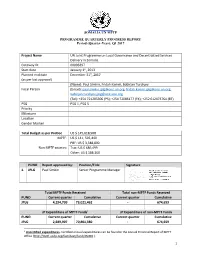

SOMALIA UN MPTF PROGRAMME QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT Period (Quarter-Year): Q1 2017 Project Name UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Services Delivery in Somalia. Gateway ID 00096397 Start date January 1st, 2013 Planned end date December 31st, 2017 (as per last approval) (Name): Paul Simkin, Fridah Karimi, Bobirjan Turdiyev. Focal Person (Email): [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] (Tel): +254 721205306 (PS); +254 72086177 (FK); +252 612473764 (BT) PSG PSG 1, PSG 5 Priority Milestone Location Gender Marker Total Budget as per ProDoc US $ 145,618,908 MPTF: US $ 141, 595,449 PBF: US $ 3,348,800 Non MPTF sources: Trac: US $ 486,499 Other: US $ 188,160 PUNO Report approved by: Position/Title Signature 1. JPLG Paul Simkin Senior Programme Manager Total MPTF Funds Received Total non-MPTF Funds Received PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative JPLG 4,294,709 73,021,462 - 674,659 JP Expenditure of MPTF Funds1 JP Expenditure of non-MPTF Funds PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative JPLG 2,689,907 70,801,380 - 674,659 1 Uncertified expenditures. Certified annual expenditures can be found in the Annual Financial Report of MPTF Office (http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/4SO00 ) 1 SOMALIA UN MPTF Acronyms PEM – Public Participatory Planning and AG – Accountant General or Auditor General Expenditure Management AIMS – Accounting Information Management PICD – Participatory Integrated Community System Development ALGPL– Association of Local -

Somalia: Window of Opportunity for Addressing One of the World's Worst Internal Displacement Crises 9

SOMALIA: Window of opportunity for addressing one of the world’s worst internal displacement crises A profile of the internal displacement situation 10 January 2006 This Internal Displacement Profile is automatically generated from the online IDP database of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). It includes an overview of the internal displacement situation in the country prepared by the IDMC, followed by a compilation of excerpts from relevant reports by a variety of different sources. All headlines as well as the bullet point summaries at the beginning of each chapter were added by the IDMC to facilitate navigation through the Profile. Where dates in brackets are added to headlines, they indicate the publication date of the most recent source used in the respective chapter. The views expressed in the reports compiled in this Profile are not necessarily shared by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The Profile is also available online at www.internal-displacement.org. About the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, established in 1998 by the Norwegian Refugee Council, is the leading international body monitoring conflict-induced internal displacement worldwide. Through its work, the Centre contributes to improving national and international capacities to protect and assist the millions of people around the globe who have been displaced within their own country as a result of conflicts or human rights violations. At the request of the United Nations, the Geneva-based Centre runs an online database providing comprehensive information and analysis on internal displacement in some 50 countries. Based on its monitoring and data collection activities, the Centre advocates for durable solutions to the plight of the internally displaced in line with international standards. -

SOMALI PACE PROJECT - Contract No

PACE Somal i Component AFRICAN UNITY - INTERAFRICAN BUREAU OF ANIMAL RESOURCES PAN AFRICAN PROGRAMME FOR THE CONTROL OF EPIZOOTICS IMPLEMENTED by TERRA NUOVA, UNA, VSF-SUISSE and CAPE Funded by EUROPEAN DEVELOPMENT FUND PROJECT No. REG/5007/005 EDF VII and VIII FINANCING AGREEMENT No. 61215/REG SOMALI PACE PROJECT - Contract No. PACE/EDF/TN/001/01 MAE (Italian Co-operation) - Contract No. PACE/IT-COF/TN/001/02 And SWISS HUMANITARIAN AID Veterinarmedizinische Hilfe Puntland, Somalia - Contract No. 7F-01353.01 (Somalia) NARRATIVE QUA ERLY REPORT 01/07/02 - 30/09/02 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS 8 I. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND OVERVIEW 9 1.1 THE PACE SOMALIA COMPONENT 9 2. SOMALI PACE OBJECTIVES 9 3. EXPECTED RESULTS 9 4. ACTIVITIES 10 RESULT 1: CAPABILITIES OF PUBLIC SECTOR AHWs TO REGULATE, COORDINATE, MONITOR AND EVALUATE THE LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT SECTOR ARE STRENGTHENED 1 1 i) Somaliland 11 ii) Puntland 13 iii) Comments 14 RESULT 2: THE CAPABILITIES OF PRIVATE ANIMAL HEALTH WORKERS TO ENGAGE IN CURATIVE AND PREVENTIVE SERVICES ARE ENHANCED. 15 i) Private sector and community based animal health strategy 15 ii) Somaliland 15 iii) Puntland 16 iv) Central Somalia 16 v) Comments 1 7 RESULT 3 & 4 LIVESTOCK DISEASE SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM WITH AN EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE COMPONENT ON IS FUNCTIONING. 17 i) Somaliland 1 7 it) Puntland 18 iii) Central Somalia 18 iv) Southern Somalia 19 v) Comments 19 RESULT 5: LOCAL/REGIONAL NETWORKS FOR ANIMAL HEALTH ARE FUNCTIONING 20 i) Somaliland 20 ii) Puntland 20 iii) Comment 20 RESULT 6: THE PROGRAMME IS EFFECTIVELY COORDINATED 20 6. -

Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin #28

Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin #28 October 2009 The Somalia Health Cluster Bulletin pro- vides an overview of the health activities conducted by the health cluster partners operating in Somalia. The Health Cluster Bulletin is issued on a monthly basis; and is available online at www.emro.who.int/somalia/healthcluster Contributions are to be sent to Child in Banadir hospital for AWD treatment Photo: WHO [email protected] HIGHLIGHTS 2 cases of Cholera in Banadir hospital have been laboratory confirmed. War casualties were the major challenge for health partners in South Central Somalia after con- flict and fighting erupted in Kismayo, Afmadow, and continued in Mogadishu. Health cluster submitted 36 projects amounting to US$ 46,444,971 to the CAP 2010. Seasonal rains (short Deyr) have started in Puntland, Somaliland, and in the Jubba and Shabelle catchments. A flooding contingency plan for Somalia is in place. SITUATION OVERVIEW On 1 October, fighting erupted between two Islamist groups in Kismayo (Lower Jubba). Based on information from various sources, WHO estimates over 80 people were killed and estimated more than 410 wounded, most affecting adult males. Trauma was mainly due to gunshots and shrapnel. The hospital¹ is struggling with the high caseload and is in need of trained health pro- fessionals. ICRC sent emergency medical supplies to various medical facilities in Kismayo, Mar- heere, Dobley, Afmadow and Jilib districts in Middle and Lower Juba. SRCS also sent two trauma surgeons and an anesthesiologist to Kismayo to support the local hospital, taking with them 400kg of surgical supplies from ICRC to treat war-wounded patients. -

Somalia 2021 Gu Seasonal Monitor, June 5, 2021

SOMALIA Seasonal Monitor June 05, 2021 FEWS NET publishes a Seasonal Monitor for Somalia every 10 days (dekad) through the end of the current April to June gu rainy season. The purpose of this document is to provide updated information on the progress of the gu season to facilitate contingency and response planning. This Somalia Seasonal Monitor is valid through June 10, 2021, and is produced in collaboration with U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU) Somalia, the Somali Water and Land Information System (SWALIM), a number of other agencies, and several Somali non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Most of Somalia continued to receive little to no rainfall through the end of May Continuing a trend of low rainfall since mid-May, field reports indicate that most of Somalia received little or no rainfall during the May 21-31 period. According to preliminary CHIRPS remote sensing data, however, most of the country received less than 10 mm (mm) of rain, while localized areas in Juba, Bay, Shabelle, and Nugaal regions received 10 to 25 mm of rain. (Figure 1). Compared to the long-term average (1981-2018), total precipitation in most of northwestern and southern Somalia was 10-25 mm below average. In the rest of the country, rainfall totals were climatologically average (Figure 2). According to the most recent FAO SWALIM river station gauge data, water levels at key monitoring points along the Shabelle and Juba rivers have significantly receded and are currently well below moderate flood risk levels. The decline is attributed to low rainfall over both Somalia’s riverine areas and the upstream river catchments in the Ethiopian highlands. -

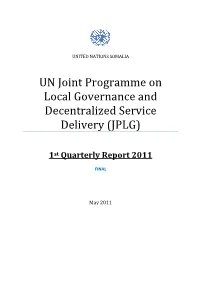

UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG)

UNITED NATIONS SOMALIA UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) 1st Quarterly Report 2011 FINAL May 2011 UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralised Service Delivery JPLG 1st Quarterly Report January – March 2011 Central Administrations of Somaliland, Puntland and the Transitional Federal Government and target Partner(s): District Councils. Joint Programme Title: UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Service Delivery (JPLG) Total Approved Joint US$ 37,187,000 Programme Budget: Location: Somaliland, Puntland and south central Somalia SC Approval Date: April 2008 Starting Completion 31/12/ Joint Programme 2008 – 2012 01/04/2008 Date: Date: 12 Duration: 2009 -2010 Through JP pass through with UNDP as AA: Donor Donor Currency USD SIDA 30,000,000 SK 3,813,361 DFID 2,275,000 GBP 3,482,109 Danida 15,000,000 DEK 2,672,511 Norway 6,000,000 NOK 1,002,701 Through JP and bilateral EC to UNDP 5,000,000 Euro 7,350,000 Sub total JP Funds 18,320,682 % of Funds Committed: Parallel Funds 2009 -2011 67% Approved: UNDP Italy: $1,800,00; 1,800,000 USAID: $1,757,428 1,757,428 DK:$693,823 693,823 Norway: $723,606 723,606 UNDP TRAC: $100,000 100,000 SIDA: $132,000; 132,000 BPCR: $132,930 132,930 UNHabitat Italy: 866,775 Euro 1,243,400 Sub total Parallel Funds 5,860,511 UNCDF $832,000 TOTAL APPROVED 2009 – 2010 25,013,704 % of Donor USD committed 75% SIDA 3,813,361 DFID 3,482,109 2009/2011: EC 6,051,447 Funds Disbursed: Danida 87,000 Norway 35,000 UNDP/parallel 2,282,771 % of 50% UNDP/USAID 1,758,428 approved UN Habitat/parallel 587,535 UNCDF 232,500 TOTAL 18,330,151 Delay Expected Duration: 5 years Forecast Final Date: December 2012 6 (Months): 2 UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralised Service Delivery EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this reporting period US$3,248,902 has been disbursed against an annual workplan and budget of US$23.3M and of which US$17,456,249 is currently available or committed. -

GHA Regional Rain Watch

SOMALIA Rain Watch May 15, 2009 FEWS NET will publish a Rain Watch for Somalia every dekad through the end of the current Gu rains (April-June) rainy season. The purpose of this document is to provide updated information on the progress of the Gu rains to facilitate contingency and response planning. This Somalia Rain Watch is valid through May 20, 2009 and is produced in collaboration with USGS, the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit (FSNAU) Somalia, a number of other agencies, and several Somali NGOs. Gu rains intensify in southern regions and parts of the north but remains poor in central and northeast. The performance of gu rains continue to be mixed in different parts of the country. Good gu rains ranging from 25 to 75 mm were received in many parts of the southern agricultural regions during the first dekad of May (1‐10), 2009. Recent information from the field confirms that, inl Centra and parts of the North, and Northeast, however, rains received so far in key pastoral areas were localized and poorly distributed. Of particular concern are Togdheer, Sool, Sanaag, Nugaal, Bari, and Mudug regions which experienced rain failure coupled with strong dry spell. In those regions gu rains normally start in early April and end late June in which heavy downpour is expected in the first two weeks of May. But the current gu season experienced unprecedented and extraordinary delay of the rains, with the exception of sporadic single day showers received in April 15th on few grazing catchments scattered in the areas. These areas attracted huge influx of herders with their stocks using motorized transportation in large scale from drier areas irrespective to administrative borders or security issues downplaying previous clan conflicts.