What's to Be Done? : a Romance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol

The Government Inspector (or The Inspector General) By Nikolai Gogol (c.1836) Translated here by Arthur A Sykes 1892. Arthur Sykes died in 1939. All Gogol’s staging instructions have been left in this edition. The names and naming tradition (use of first and family names) have been left as in the original Russian, as have some of the colloquiums and an expected understanding of the intricacies of Russian society and instruments of Government. There are footnotes at the end of each Act. Modern translations tend to use the job titles of the officials, and have updated references to the civil service, dropping all Russian words and replacing them with English equivalents. This script has been provided to demonstrate the play’s structure and flesh out the characters. This is not the final script that will be used in Oxford Theatre Guild’s production in October 2012. Cast of Characters ANTON ANTONOVICH, The Governor or Mayor ANNA ANDREYEVNA, his wife. MARYA ANTONOVNA, his daughter. LUKA LUKICH Khlopov, Director of Schools. Madame Khlopov His wife. AMMOS FYODOROVICH Lyapkin Tyapkin, a Judge. ARTEMI PHILIPPOVICH Zemlyanika, Charity Commissioner and Warden of the Hospital. IVANA KUZMICH Shpyokin, a Postmaster. IVAN ALEXANDROVICH KHLESTAKOV, a Government civil servant OSIP, his servant. Pyotr Ivanovich DOBCHINSKI and Pyotr Ivanovich BOBCHINSKI, [.independent gentleman] Dr Christian Ivanovich HUBNER, a District Doctor. Karobkin - another official Madame Karobkin, his wife UKHAVYORTOV, a Police Superintendent. Police Constable PUGOVKIN ABDULIN, a shopkeeper Another shopkeeper. The Locksmith's Wife. The Sergeant's Wife. MISHKA, servant of the Governor. Waiter at the inn. Act 1 – A room in the Mayor’s house Scene 1 GOVERNOR. -

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 A Century of Restorations Originally published as Das Jahrhundert der Restaurationen, 1814 bis 1906, Munich: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014. Translated by Volker Sellin An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-052177-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052453-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052209-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772–1851): Allégorie du retour des Bourbons le 24 avril 1814: Louis XVIII relevant la France de ses ruines. Musée national du Château de Versailles. bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Introduction 1 France1814 8 Poland 1815 26 Germany 1818 –1848 44 Spain 1834 63 Italy 1848 83 Russia 1906 102 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 126 Index 139 Introduction In 1989,the world commemorated the outbreak of the French Revolution two hundred years earlier.The event was celebratedasthe breakthrough of popular sovereignty and modernconstitutionalism. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

Artist (Surnamne, First Name

artist (surnamne, first name YoB - YoD) pseudonym presumed nationality Abakoumov, Michail - (1948 - ) Russia Abdelkader, Guermaz - (1919 - 1996) Algeria Aceves, Tomas - ( - ) Spain Ackema, Tjeerd - (1929 - ) Netherlands Adams, Harry William - (1868 - 1947) United Kingdom Adams, Walter - ( - ) USA Adan, Louis Émile - (1839 - 1937) France Adgamow, Rachit - (1951 - ) Russia Adler, Edmund - Edmund Rode(1876 - 1965) Edmund Rode Austria Adler, Yankel - (1895 - 1949) Poland Adreeko-Nechitalio, Mihail Fjodorovitj - (1894 - 1982) Russia Aereboe, Albert - (1889 - 1970) Germany Affleck, William - (1869 - 1943) United Kingdom Agafonoff, Eugene - (1879 - 1956) Ukraine Agterberg, Cris - (1883 - 1948) Netherlands Ahola, Hilkka-Liisa - ( - ) Finland Akino, Yoko - (1967 - ) Ireland Akkeringa, Johannes - (1861 - 1942) Netherlands Akopov, Alexander - (1979 - ) Russia Alaux, Jean-Pierre - ( - ) France Albert, Bitran - (1929 - ) Turkey Alberti, Guiseppe Vizzotto - (1862 - 1931) Italy Aldoma Puig, Artur - (1935 - ) Spain Alico, Giovanni - (1906 - 1971) Italy Aliotti, Claude - (1925 - 1989) France Allart, Patrice - (1945 - ) France Allavena, Michele - (1863 - 1949) Italy Alliot, Lucien - (1877 - 1956) France Allmann, Albert - (1890 - 1979) Germany Alonzo, Dominiqe - ( - ) France Alvárez Lencero, Luis - (1923 - ) Spain Alves, Jose - (1954 - ) Portugal Alys, Francis - (1959 - ) Belgium Aman-Jean, Edmond - (1858 - 1936) France Amaya, Marino - (1926 - ) Spain Ames Swartz, Beth - (1936 - ) USA Ameseder, Eduard - ( - 1938) Austria Amorosolo y Cueta, Fernando - (1892 -

A LISBONA PARALISI POLITICA Violenze Anticomuniste Nel Paese

Quotidiano / Anno Lll / N. 225 C\'r%Tv?o) * Mercoledì 20 agosto 1975 / L ISb Atene: pena di morte In Spagna sarebbero per Papadopulos e imminenti importanti altri quindici imputati ? cambiamenti al vertice A pag. 11 l'Unità A pag. 12 ORGANO DEL PARTITO COMUNISTA ITALIANO UN MILITANTE DEL PCP UCCISO DA UN SOLDATO Dramma nei quartiere povero della città Madre e due figli A LISBONA PARALISI POLITICA muoiono nel crollo Violenze anticomuniste nel Paese della casa a Trapani Il palazzo pieno di crepe e da anni inabitabile si è sgretolato Il gravissimo comportamento del reparto inviato davanti alla sede comunista di Ponte de Lima assalita dai reazionari • Voci allarmanti: due generali di destra assumerebbero in pochi minuti — La disperata opera di soccorso — Altri tre la direzione del « gruppo dei nove » - Drammatico ammonimento di Goncalves contro intrighi e cospirazioni • Comunicato del PCP sulla situazione nel nord del paese feriti gravissimi — Tra le vittime anche un piccino di otto mesi | questi termini la situazione Dal nostro inviato I del Paese: « Ad ogni Istante Dal nostro corrispondente TRAPANI 19 LISBONA, 19. 1! la situazione si altera di- Nel cuore del centro storico, a due passi dal Palazzo del governo, in uno del quartieri Un compagno ucciso, due ventando più confusa e in più poveri ed abbandonati della città, oggi pomeriggio all'ora di pranzo è crollata, d'un mitri in condizioni gravissi stabile, o definendosi ma in colpo, la casa — dichiarata « In buono stato » sei mesi fa dall'ufficiale sanitario del comu me, oltre un centinaio di fe senso contraddittorio. Si riti (un soldato e due vigili succedono riunioni, docu ne — abitata dalla famiglia Rosselli che inutilmente si è battuta, in questi anni, por con del fuoco in modo preoccu menti, discussioni, piattafor quistare una vera abitazione, di quelle popolari costruite alla periferia di Trapani. -

AUTHORS of FLY NAMES Second Edition

AUTHORS OF FLY NAMES Second Edition Neal L. Evenhuis Bishop Museum 2013 AUTHORS OF FLY NAMES A list of all authors who have proposed Diptera names at the family-level or below Second Edition Neal L. Evenhuis Bishop Museum Technical Report No. 61 2013 Published by Bishop Museum 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawaii 96817 Copyright ©2013 Author contact information: Dr. Neal L. Evenhuis Bishop Museum 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawaii 96817-2704, USA email: [email protected] ISSN 1085-455X Introduction This is the second edition of this list. The first edition was published in 2010 as Bishop Museum Technical Report 51. That 2010 list included 5,375 dipterists. This second edition lists 5,701, an increase of 326 in just a little over two years. I began in the late 1980s to compile an authority file of all authors who had proposed at least one or more names of extant and/or fossil Diptera taxa at family level or below. The need for this list stemmed from two focal points: 1) to provide a unambiguous (i.e., unique) identifier for every author who proposed a dipteran name; and 2) to provide to a wide user-community basic biographical information on authors of fly names in order to allow accurate identification of these authors and for general interest in just who were these people describing fly names. Authority files are comprised of entries that are used as templates for associations with and cross-indexing in bibliographies, taxon lists, collection information, and other sets of data. As such, having as accurate a set of data as possible pertaining to those entries is required in order to avoid ambiguities. -

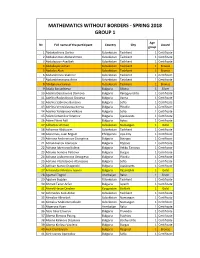

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2018 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2018 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdukadirova Darina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdukarimov Abdurahmon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 3 Abdulazizov Asadbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 4 Abdullayev Adnan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 5 Abdulov Alan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdurahimov Shahrier Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdurakhmanova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 8 Abidjanova Sureya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 9 Adalia Barutchieva Bulgaria Silistra 1 Silver 10 Adelina Desislavova Dankova Bulgaria Panagyurishte 1 Certificate 11 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 12 Adelina Sabinova Borisova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 13 Adelina Ventsislavova Koeva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 14 Adelina Yordanova Velkova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 15 Adem Dzhemilov Ademov Bulgaria Lyaskovets 1 Certificate 16 Adem Fikret Adil Bulgaria Aytos 1 Certificate 17 Adhamov Ahmad Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Gold 18 Adkamov Abduazim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 19 Adoremos, Juan Miguel Philippines Lipa City 1 Certificate 20 Adreana Andreanova Georgieva Bulgaria Bourgas 1 Certificate 21 Adrian Ivanov Atanasov Bulgaria Popovo 1 Certificate 22 Adriana Iskrenova Koleva Bulgaria Veliko Tarnovo 1 Certificate 23 Adriana Ivanova Petkova Bulgaria Burgas 1 Certificate 24 Adriana Lyubomirova Georgieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 25 Adriana Vladislavova Atanasova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 26 Adriyan Ivanov Draganski Bulgaria -

Commencement

Commencement College of Life Sciences and Agriculture College of Engineering and Physical Sciences May 21, 2021 Celebrate 1 PROGRAM GUIDE Page Number University System of New Hampshire Board of Trustees 1 Platform Party 2 Commencement Program 3 Honorary Degree 5 Granite State Awards 6 Faculty Marshals 8 Class Marshals 8 Honors 10 College of Life Sciences & Agriculture Thompson School of Applied Science 16 Bachelors 16 College of Engineering & Physical Sciences Bachelors 24 Academic Regalia 31 Alma Mater 33 UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE COMMENCEMENT MAY 21, 2021 WILDCAT STADIUM, 4 p.m. UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF NEW HAMPSHIRE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseoph G. Morone, Chair James P. Burnett, Vice Chair Kassandra Spanos Ardinger, Secretary The Honorable Christopher T. Sununu, Governor, Ex-Officio Amy Begg Donald L. Birx, President, Plymouth State University, Ex-Officio Todd R. Black James W. Dean Jr., President, University of New Hampshire, Ex-Officio M. Jacqueline Eastwood Frank Edelblut, Commissioner of Education, Ex-Officio James Gray, Designee for the President of the Senate, Ex-Officio Cathy J. Green George Hansel Shawn N. Jasper, Commissioner, New Hampshire Department of Agriculture, Ex-Officio Rick Ladd, Designee for the Speaker of the House, Ex-Officio Tyler Minnich Michael J. Pilot Christopher M. Pope Mark Rubinstein, President, Granite State College, Ex-Officio J. Morgan Rutman Wallace R. Stevens Gregg R. Tewksbury Melinda D. Treadwell, President, Keene State College, Ex-Officio Alexander J. Walker Jr. David Westover 1 PLATFORM PARTY James W. Dean Jr. President Wayne Jones Provost Nicholas Fitzgerald Student Body President Erin Sharp Chair, Faculty Senate Anthony Davis Dean, College of Life Sciences and Agriculture Cyndee Gruden Dean, College of Engineering and Physical Sciences Ken Holmes Senior Vice Provost for Student Life Kate Ziemer Senior Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Sharon McCrone Associate Dean, College of Engineering and Physical Sciences 2 COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM PROCESSIONAL Pomp and Circumstance University Wind Symphony Andrew A. -

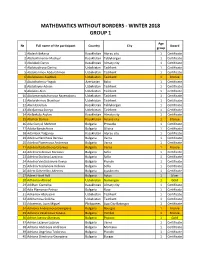

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2018 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2018 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdesh Bekarys Kazakhstan Atyrau city 1 Certificate 2 Abdrakhmanov Madiyar Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 1 Certificate 3 Abdubek Daryn Kazakhstan Almaty city 1 Certificate 4 Abdukadirova Darina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 5 Abdukarimov Abdurahmon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 6 Abdulazizov Asadbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 7 Abdulhalimov Yagub Azerbaijan Baku 1 Certificate 8 Abdullayev Adnan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdulov Alan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 10 Abdumannobzhonova Rayenabonu Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdurahimov Shaxriyor Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 12 Aben Ersultan Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 1 Certificate 13 Abidjanova Sureya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 14 Abilbekuly Asylan Kazakhstan Almaty city 1 Certificate 15 Abylkali Daniya Kazakhstan Astana city 1 Bronze 16 Ada Gunyul Mehmet Bulgaria Provadia 1 Certificate 17 Adalia Barutchieva Bulgaria Silistra 1 Certificate 18 Adambek Tolganay Kazakhstan Atyrau city 1 Certificate 19 Adelina Nencheva Berova Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 20 Adelina Plamenova Andreeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 21 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 22 Adelina Sabinova Borisova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 23 Adelina Stoilova Lazarova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 24 Adelina Ventsislavova Koeva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Yordanova Velkova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 26 Adem Dzhemilov Ademov Bulgaria Lyaskovets 1 Certificate -

Nummer 06/10 24 Maart 2010 Nummer 06/10 1 24 Maart 2010

Nummer 06/10 24 maart 2010 Nummer 06/10 1 24 maart 2010 Inleiding Introduction Hoofdblad Patent Bulletin Het Blad de Industriële Eigendom verschijnt op de The Patent Bulletin appears on the 3rd working derde werkdag van een week. Indien NL day of each week. If the Netherlands Patent Octrooicentrum op deze dag is gesloten, wordt de Office is closed to the public on the above verschijningsdag van het blad verschoven naar de mentioned day, the date of issue of the Bulletin is eerstvolgende werkdag, waarop Octrooicentrum the first working day thereafter, on which the Nederland is geopend. Het blad verschijnt alleen in Office is open. Each issue of the Bulletin consists electronische vorm. Elk nummer van het blad bestaat of 14 headings. uit 14 rubrieken. Bijblad Official Journal Verschijnt vier keer per jaar (januari, april, juli, Appears four times a year (January, April, July, oktober) in electronische vorm via de website van NL October) in electronic form on the website of the Octrooicentrum. Het Bijblad bevat officiële Netherlands Patent Office. The Official Journal mededelingen en andere wetenswaardigheden contains announcements and other things worth waarmee NL Octrooicentrum en zijn klanten te maken knowing for the benefit of the Netherlands Patent hebben. Office and its customers. Abonnementsprijzen per (kalender)jaar: Subscription rates per calendar year: Hoofdblad en Bijblad: verschijnt gratis in Patent Bulletin and Official Journal: free of electronische vorm op de website van NL charge in electronic form on the website of the Octrooicentrum. -

Materiały Do Bibliografii Do Łacińskiej Serii Testimoniów Najdawniejszych Dziejów Słowian

INSTYTUT SLAWISTYKI POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK TOWATOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE WAWARSZAWSKIE MATEriAłY DO BIBLIOGRAFII DO łACIńSKIEJ SErii TESTIMONIÓW NAJDAWNIEJSZYCH DziEJÓW SłOWIAN 123 http://rcin.org.pl http://rcin.org.pl MATERIAłY DO BIBLIOGRAFII DO łACIńSKIEJ SERII TESTIMONIÓW NAJDAWNIEJSZYCH DZIEJÓW SłOWIAN http://rcin.org.pl Prace Slawistyczne 123 Komitet Redakcyjny EWA RZETELSKA-FELESZKO (przewodnicząca) JERZY DUMA, JACEK KOLBUSZEWSKI, VIOLETTA KOSESKA-TOSZEWA, HANNA POPOWSKA-TABORSKA, JANUSZ SIATKOWSKI, LUCJAN SUCHANEK http://rcin.org.pl INSTYTUT SLAWISTYKI POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK TOWARZYSTWO NAUKOWE WARSZAWSKIE MATERIAłY DO BIBLIOGRAFII Do łACIńSKIEJ SERII TESTIMONIÓW NAJDAWNIEJSZYCH DZIEJÓW SłOWIAN UłOżYł I WSTęPEM POPRZEDZIł Ryszard Grzesik WARSZAWA 2007 http://rcin.org.pl Publikację opiniowali do druku Andrzej Wędzki i Tomasz Jurek Wydanie publikacji dofinansowane przez Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego Projekt okładki Marek Pijet Redakcja Zenobia Mieczkowska Skład i łamanie Katarzyna Sosnowska-Gizińska © Copyright by Ryszard Grzesik & Slawistyczny Ośrodek Wydawniczy & Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie Printed in Poland ISBN 978-83-89191-64-9 Slawistyczny Ośrodek Wydawniczy (SOW) Instytut Slawistyki PAN Pałac Staszica, ul. Nowy Świat 72, 00-330 Warszawa tel./fax (0-22) 826 76 88, tel. 827 17 41 [email protected], www.ispan.waw.pl http://rcin.org.pl WSTęP Od trzydziestu bez mała lat trwają prace nad wydaniem serii wydawniczej Testimonia najdawniejszych dziejów Słowian. Od po- czątku pomyślane one zostały jako wydawnictwo zamieszczające ekscerpty ze źródeł niesłowiańskich wzmiankujących (najczęściej mimochodem) ludy słowiańskie. Zebranie tego typu wzmianek po- kazuje, w jaki sposób Słowianie postrzegani byli przez przedstawicieli świata intelektualnego ówczesnych centrów cywilizacyjnych: schył- kowego Cesarstwa Rzymskiego i jego politycznej kontynuacji, znanej w historiografii jako Cesarstwo Bizantyjskie, krajów sukcesyjnych Rzymu, imperium karolińskiego i Europy pokarolińskiej.