Dr. Cornejo Tenure Letter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian Ecosocialist

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7049 Peru Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist - Features - Publication date: Thursday 22 April 2021 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist "Of course I am an ecosocialist, as are the indigenous peoples even if they do not use that term". Hugo Blanco is one of the figures in the struggle for emancipation in Peru. In the 1960s, he played an important role in the revolutionary mobilization of indigenous peasants against the four-century-old dominant agrarian regime latifundism. During a self-defence action, a policeman was killed; Blanco was sentenced to death. Defended by Amnesty International, Sartre and de Beauvoir, he lived in exile in the 1970s: in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and then, in the aftermath of the coup against Allende, in Sweden. Returning home, he joined the Peasant Confederation and became a member of parliament, then a senator under the colours of Izquierda Unida a coalition of left-wing organizations. At the age of 86, he currently [2021] resides in Sweden, retired from "political life". Last month, during the screening of a documentary tracing his career, the Peruvian far right campaigned against him. This is an interview published in his native country: he looks back on his life as an activist. Tell us about your life: were you a peasant or a student? My mother was a small landowner and my father was a lawyer. He had a brother who was studying at La Plata (in Argentina). -

Ponciano Del Pino H

Dear Agrarian Studies Readers: This paper summarizes the main arguments of two chapters in which memories of the Shining Path’s violence are situated in the framework of longer historical memory and state-making from 1920s to 1960s. Beyond the immediate past, land insecurity and conflict, the politics of articulation, and government as idea, political language and identity, shape people’s memory, as well as the position assumed by the communities in the context of the 1980s violence. The book manuscript I am working on explores memories of violence at different levels: I emphasize the production of silences and secrets as the central dynamic in the production of memory on the Shining Path’s Peru. This immediate past is framed in the longer historical memory, the politics of articulation and state-making. Finally, the historicity of memory and violence is seen in memory places, landscape and nature, insofar as those were not outsiders to the violence. I analyze narratives about the power of the mountains and their present weakness, which seems to be the case in the context of melting ice. The environmental change provides another window into communities’ experience of natural and social vulnerability in the context of the state pressure and expansion throughout the twentieth century. This multilevel subjective, political and historical experience of the highland communities of Ayacucho, Peru, not only shapes local politics and culture but also exposes the relation between the process of nation-state formation and transformation, and of colonialism as a global process of domination, which lies at the heart of twentieth-century politics in Peru and many other countries of Latin America. -

Redalyc.Koka Mama

Argumentos ISSN: 0187-5795 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco México Blanco, Hugo Koka Mama Argumentos, vol. 19, núm. 50, enero-abril, 2006, pp. 117-140 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59501906 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MUNDO ANDINO: HISTORIA, CULTURA Y REBELIÓN DOSSIER KOKA MAMA Hugo Blanco* La “coca” es un emblema de la antigua cultura andina: es la hoja sagrada. Tiene un signifi- cado religioso, social y medicinal desde hace seis mil años. La política imperial de Estados Unidos difunde la idea según la cual “coca es igual a cocaína” para combatir a los pueblos andinos y despojarlos de sus riquezas naturales. KOKA MAMA The “coca” is a symbol of the ancient Andean culture: it is the sacred leaf. It has had a religious, social and medical meaning for more than six thousand years. The imperial policy of the United States disseminates the idea that “coca” and cocaine are the same thing, to attack the Andean villages and deprive them from their natural resources. KOKA MAMA La “coca” est un emblème de l’ancienne culture andine : elle est feuille sacrée. La “coca” a une signification religieuse, social et médicinale depuis six mille ans. La politique impériale des Etats-Unis répand l’idée selon laquelle la “coca” est “cocaïne” pour combattre les peuples andins et les dépouiller de leurs ressources naturelles. -

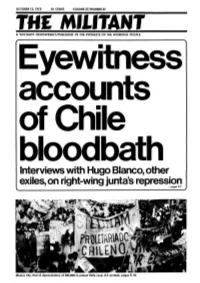

Interviews with Hugo Blanco, Other Exiles, on Right-Wing Junta's Repression · -Pages 5-7

OCTOBER 12, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 37 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE II Interviews with Hugo Blanco, other exiles, on right-wing junta's repression · -pages 5-7 Mexico City. Part of demonstration of 100,000 to protest Chile coup. U.S. protests, pages 9, 10. ln.Briel MICHIGAN STUDENTS OPPOSE TUITION HIKE: Stu in San Francisco last March of the tenth anniversary dents at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are of the CIA-backed coup that brought the shah of Iran THIS organizing a tuition strike to roll back a 24 percent fee to power. hike passed by the board of regents this summer. Widespread protests forced the dropping of the assault WEEK'S The Student Action Committee, which is coordinating charges. But Shokat and Ghaemmagham pleaded guilty the strike, held a rally of 250 students on Sept. 28, despite to the lesser charge of "intimidation" to bring the case MILITANT pouring rain. Militant correspondent Marty Pettit reports to an end. 3 UFW-Teamster talks the protesters then lined up in front of collection windows ·The Iranian Student Association has urged protests 4 Boudin describes gov't in the registration area and successfully prevented cashiers against these sentences, especially the imposition of the from accepting payments. maximum jail term on Shokat. Write to: Honorable Judge attempts to discredit him Strike leader Ruy Teixeira said, "A lot of people see this Williams, Federal Building, Nineteenth Floor, 450 Golden 8 New evidence of mass whole struggle, which hopefully will become nationwide, Gate Ave., San Francisco, <_::alif. -

Hugo Blanco: "I Was Neither a 'Castroite Guerrilla' Nor a 'Terrorist'"

Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6916 Peru Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV550 - November 2020 - Publication date: Monday 23 November 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" Hugo Blanco lives in Mexico, but he travelled to Europe to meet his new German-born granddaughter. Before that, he wanted to go and see his daughter Carmen in Sweden and it was there that the pandemic took him by surprise. Farik Matuk put us in touch with Carmen Blanco, who kindly asked us to send the questions in writing, because Hugo Blanco "can no longer answer by telephone". Here are the answers to the controversy sparked off by the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo (in English Hugo Blanco, Deep River). Roberto Ochoa: Are you aware of the turmoil caused by the screening of the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo? Hugo Blanco: Yes, I am aware of the turmoil caused in Peru and internationally. And I am also moved by the multiple expressions of solidarity that reach me from several places in Peru and around the world. From those who are leading struggles close to mine, but also from young people who until then did not know of my existence, but who are now interested in my trajectory of struggles. Every day, dozens of solidarity messages reach me and my daughter Carmen by email and other social networks. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Hugo Blanco Interview: 'Why Kissinger Won't Let Me Speak' PAGE 7

OCTOBER 24, 1975 · 25 CENTS VOLUME 39/NUMBER 39 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE 2f YEARS /$ TOO lON(J/. OEFENO .u&..I"'''VII · .u·•rLILI 2nd NATiONAL STUDENTS CON-:·.... _.,..lliil .•~.: ... } <·· AGAINST·:RA.CISM NORTHEASTERN MilitanVLou Howort Boston, October 11. The 1,200 participants in National Student Conference Against Racism set plans for November 22 actions to defend school desegregation. Pages 4-6. Hugo Blanco interview: 'WhY Kissinger won't let me speak' PAGE 7 'N.Y. Times' editors tell FBI to stop harassing socialists PAGE 3 In Brief THIS RACIST VIOLENCE IN LOUISVILLE.•• : Racists of their central strike leader by a scab truck driver and conducted a campaign of violence aimed at halting school numerous arrests of picketers, "spirit is high after nine WEEK'S desegregation in Louisville, Kentucky, last week. On weeks,'' said one Chicana striker. "It looks like the first Thursday night, October 9, a school bus was bombed. The day." MILITANT next day police arrested a white youth who had assaulted a Black student with a baseball bat as he was getting off a 3 'N.Y. Times' tells FBI school bus. Later that day, three Black students were PEOPLE'S PARTY RUNS SPOCK: Citing other activi to stop harassing SWP injured by flying glass when a brick shattered a window of ties and time constraints that would prevent her from -4 NSCAR conference maps the bus they were riding in. actively campaigning, Maggie Kuhn has withdrawn as the People's party candidate for vice-president in 1976. Kuhn is national actions On Sunday night, police used tear gas to disperse a·crowd of 500 antibusing demonstrators in suburban Jefferson a leader of the Gray Panthers, a group concerned with the 7 Interview with town. -

REVISTA CONVERGÊNCIA CRÍTICA V

REVISTA CONVERGÊNCIA CRÍTICA v. 2, n. 9 (2016) TERRA E HUMANIDADE: HUGO BLANCO - DA LUTA PELA REFORMA AGRÁRIA À DEFESA DA ESPÉCIE HUMANA Vanderlei Vazelesk Ribeiro Unirio Resumo: Neste trabalho discutiremos a atuação do dirigente camponês Hugo Blanco que, desde a década de 50, milita em movimentos camponeses no Peru, tendo também importante participação, tanto nos círculos trotskistas internacionais, como nos atuais movimentos indígenas e ambientalistas. Avaliaremos sua luta nos anos 60, os anos de prisão, exílio e volta ao Peru, assim como, a sua atuação ao longo da década de 80, o novo exílio e sua identificação com questões indígenas e ambientais desde o fim do século XX. Palavras-chave: Hugo Blanco, Reforma Agrária, Questão indígena, Luta Ambiental Abstract: In this article, we will discuss the action of peasant leader Hugo Blanco, who has been in Peruvian’s peasant movements since the 1950s. He has also played an important role both in international Trotskyist circles and in the current indigenous and environmental movements. We will discuss Blanco’s struggle in the 60's, his years of imprisonment, exile and his return to Peru, as well as his action throughout the 80's, his new exile and his identification with indigenous and environmental issues since the end of the 20th century. Keywords: Hugo Blanco, Land Reform, Peruvian indigenous issues, Environmental movement Introdução: o tema da Biografia “A Humanidade pode sobreviver sem engenheiros, mas não resiste um mês sem camponeses”. [Hugo Blanco em depoimento inédito ao grupo de pesquisadores liderado pelo Professor Fábio Luiz Barbosa dos Santos. Lima, sede da Confederación Campesina del Perú, , 22 de julho de 2015]. -

Peru: Two Strategies

Nahuel Moreno Peru: Two Strategies The peasant rebellion headed by Hugo Blanco and the polemic with putschism (1961-1963) Ediciones Nahuel Moreno Nahuel Moreno: Peru Two Strategies First Spanish Edition: Estrategia, Buenos Aires, 1964 Second Spanish Edition: Ediciones Cehus, Buenos Aires, 2015 First English (Internet) Edition: Ediciones El Socialista, Buenos Aires, 2015 Other Papers: Fragments from Workers’ and Internationalist Trotskyism in Argentina, Ernesto Gonzalez (Coordinator), Editorial Antidoto, Part 3, Vol. 1, 1999. Annex: Hugo Blanco and the peasant uprising in the Cusco region (1961-1963), Hernan Camarero, Periphery; Social Science Journal No. 8, second half of 2000. English Translation: Daniel Iglesias Cover Design: Marcela Aguilar / Daniel Iglesias Interior Design: Daniel Iglesias www.nahuelmoreno.org www.uit-ci.org www.izquierdasocialista.org.ar Ediciones Index Foreword Miguel Sorans Nahuel Moreno and his fight against putschism in Trotskyism ........................................................................ 2 Peru: Two Strategies Nahuel Moreno Chapter I The peasant mobilisation is the engine of the Peruvian Revolution ................................................................ 9 Chapter ii Putsch or development of dual power? .................................................................................................................12 Chapter III Developing and centralising the agrarian revolution ........................................................................................23 Chapter IV The revolutionary -

Hugo Blanco Deported •

OCTOBER 1, 1971 25 CENTS A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE - - March protesting Attica massacre in Harlem Sept. 18, 1971. Articles about Attica and prison revolts, pages 10-15. Hugo Blanco deported • ICO- page 5 Support widens for abortion campaign/ 4 Attica victim's family tells of cruelty/13 Saigon election fraud stirs protest/17 VOLUME 35/NUMBER 35 THIS BLACK INMATE SUES PRISON OFFICIALS AT FED RADICAL ECONOMISTS BLAST NIXON'S FREEZE: ERAL PEN IN TEXAS: Walter Collins, a Black draft After holding a week of seminars near Morgantown, W. WEEK'S resister serving a fiv~year sentence at the federal prison Va., in August, the Union for Radical Political Economics in Texarkana, Texas, filed suit Sept. 14 against Warden adopted a four-page statement condemning Nixon's wage MILITANT L. M. Connett and Education SupervisorWilliam C. Storm freeze. It charged that while ''the main cause of the Nixon for refusing to allow him to receive certain books, to program lies in the capitalists' need to further rationalize 3 Subscription sales ahead mail some of his letters or to receive visits from Carl and control inherently destructive tendencies in capital in first week of drive Braden. Collins was a co-worker of Braden's in the South ism." Such control will mean a: "stronger concentration 4 Support widens for ern Conference Educational Fund before he was jailed of corporate government power" at the expense of work abortion campaign by a racist court decision refusing to recognize that Col ers power "to control the human and physical resources lins' draft board was illegally constituted. -

Finding Aid No. 2360 / Instrument De Recherche No 2360

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA/BIBLIOTHÈQUE ET ARCHIVES CANADA Canadian Archives Direction des archives Branch canadiennes Finding Aid No. 2360 / Instrument de recherche no 2360 Prepared in 2004 by John Bell of the Préparé en 2004 par John Bell de la Political Archives Section Section des archives politique. II TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction............................................................................................................................iv Series 1: Internal bulletins, 1935-1975 ....................................................................................1 Series 2: Socialist Workers Party internal information bulletins, 1935-1975 .......................14 Series 3: Socialist Workers Party discussion bulletins, 1934-1990.......................................19 Series 4: International bulletins and documents, 1934-1994 ................................................28 Series 5: Socialist League / Forward Group, 1973-1993 ......................................................36 Series 6: Forward files, 1974-2002........................................................................................46 Series 7: Young Socialist / Ligue des jeunes socialistes, 1960-1975 ....................................46 Series 8: Ross Dowson speech and other notes, 1940-1989..................................................52 Series 9: NDP Socialist Caucus and Left Caucus, 1960-1995...............................................56 Series 10: Gord Doctorow files, 1965-1986 ..........................................................................64 -

Joseph Hansen Dies in New York NEW YORK, Jan

JANUARY 26, 1979 50 CENTS VOLUME 43/NUMBER 3 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY /PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Ex-agent exposes gov'llies about FBI informers By Larry Seigle JAN. 17-A vast conspiracy to cover up crimes of FBI informers has begun to unravel. M. Wesley Swearingen, a recently retired FBI agent, has provided evi dence that the number two man in the FBI gave false information under oath in the Socialist Workers Party lawsuit against the government. The fabricated testimony is the foun IRAN: dation on which the Carter adminis tration has based its refusal to turn over files on the activities of eighteen FBI informer-provocateurs used What against the SWP and the Young So cialist Alliance. Carter's attorney general, Griffin way Bell, has even gone to the unprece dented length of placing himself in contempt of court rather than hand over these files. forward? At this very moment, a federal court of appeals is deciding whether to sus tain the contempt citation against Continued on page 6 TEHRAN-Demonstrators celebrate shah's flight by pul ling down statue of his father. See page 4. Joseph Hansen dies in New York NEW YORK, Jan. 18- in New York City. It will be Joseph Hansen (1910-1979), held at Manhattan's Marc Ball longtime leader of the Fourth room, 27 Union Square West International and the Socialist (between Fifteenth and Six Workers Party, died here today. teenth streets). Messages to the Hansen, who joined the Trot meeting should be sent in care skyist movement in 1934, was of the Militant, 14 Charles editor of the weekly socialist Lane, New York, New York magazine, Intercontinental 10014.