Argentina and Bolivia – the Balance Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian Ecosocialist

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7049 Peru Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist - Features - Publication date: Thursday 22 April 2021 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist "Of course I am an ecosocialist, as are the indigenous peoples even if they do not use that term". Hugo Blanco is one of the figures in the struggle for emancipation in Peru. In the 1960s, he played an important role in the revolutionary mobilization of indigenous peasants against the four-century-old dominant agrarian regime latifundism. During a self-defence action, a policeman was killed; Blanco was sentenced to death. Defended by Amnesty International, Sartre and de Beauvoir, he lived in exile in the 1970s: in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and then, in the aftermath of the coup against Allende, in Sweden. Returning home, he joined the Peasant Confederation and became a member of parliament, then a senator under the colours of Izquierda Unida a coalition of left-wing organizations. At the age of 86, he currently [2021] resides in Sweden, retired from "political life". Last month, during the screening of a documentary tracing his career, the Peruvian far right campaigned against him. This is an interview published in his native country: he looks back on his life as an activist. Tell us about your life: were you a peasant or a student? My mother was a small landowner and my father was a lawyer. He had a brother who was studying at La Plata (in Argentina). -

Why Mao? Maoist Insurgencies in India and Nepal Peace Conflict & Development, Issue 9, July 2006 Available From

Sean DeBlieck – Why Mao? Maoist insurgencies in India and Nepal Peace Conflict & Development, Issue 9, July 2006 available from www.peacestudiesjournal.org.uk Why Mao? Maoist insurgencies in India and Nepal By Sean DeBlieck1 1 Sean DeBlieck is the site administrator for Program on Security and Development at the Monterey Institute of International Studies (MIIS), California. He received a Masters degree from MIIS in International Policy Studies, specialising in Human Security and Development. He has served as an intern with the United Nations Development Programme’s Support for Security Sector Reform Programme in Albania, and with the US Peace Corps in Sri Lanka. 1 Sean DeBlieck – Why Mao? Maoist insurgencies in India and Nepal Peace Conflict & Development, Issue 9, July 2006 available from www.peacestudiesjournal.org.uk Introduction Although 30 years have passed since his death, Mao Tse-tung continues to inspire violent action in South Asia. Maoist rebels are active in at least nine Indian states, and were labelled in March 2006 as the greatest internal security challenge ever faced by the country.2 After a decade of war in Nepal, Maoist rebels control up to 80% of the country,3 and are now working with a coalition of political parties to rewrite the country’s constitution that will in all likelihood do away with the country’s powerful monarchy. In this essay, I examine the original Naxalite movements, the current Maoist insurgencies in India, and the ten-year Maoist insurrection that has led to fundamental changes in Nepal. The central question that I hope to answer is why Maoism has continued to inspire violent revolution so long after the Chairman’s death. -

Ponciano Del Pino H

Dear Agrarian Studies Readers: This paper summarizes the main arguments of two chapters in which memories of the Shining Path’s violence are situated in the framework of longer historical memory and state-making from 1920s to 1960s. Beyond the immediate past, land insecurity and conflict, the politics of articulation, and government as idea, political language and identity, shape people’s memory, as well as the position assumed by the communities in the context of the 1980s violence. The book manuscript I am working on explores memories of violence at different levels: I emphasize the production of silences and secrets as the central dynamic in the production of memory on the Shining Path’s Peru. This immediate past is framed in the longer historical memory, the politics of articulation and state-making. Finally, the historicity of memory and violence is seen in memory places, landscape and nature, insofar as those were not outsiders to the violence. I analyze narratives about the power of the mountains and their present weakness, which seems to be the case in the context of melting ice. The environmental change provides another window into communities’ experience of natural and social vulnerability in the context of the state pressure and expansion throughout the twentieth century. This multilevel subjective, political and historical experience of the highland communities of Ayacucho, Peru, not only shapes local politics and culture but also exposes the relation between the process of nation-state formation and transformation, and of colonialism as a global process of domination, which lies at the heart of twentieth-century politics in Peru and many other countries of Latin America. -

Redalyc.Koka Mama

Argumentos ISSN: 0187-5795 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco México Blanco, Hugo Koka Mama Argumentos, vol. 19, núm. 50, enero-abril, 2006, pp. 117-140 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59501906 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MUNDO ANDINO: HISTORIA, CULTURA Y REBELIÓN DOSSIER KOKA MAMA Hugo Blanco* La “coca” es un emblema de la antigua cultura andina: es la hoja sagrada. Tiene un signifi- cado religioso, social y medicinal desde hace seis mil años. La política imperial de Estados Unidos difunde la idea según la cual “coca es igual a cocaína” para combatir a los pueblos andinos y despojarlos de sus riquezas naturales. KOKA MAMA The “coca” is a symbol of the ancient Andean culture: it is the sacred leaf. It has had a religious, social and medical meaning for more than six thousand years. The imperial policy of the United States disseminates the idea that “coca” and cocaine are the same thing, to attack the Andean villages and deprive them from their natural resources. KOKA MAMA La “coca” est un emblème de l’ancienne culture andine : elle est feuille sacrée. La “coca” a une signification religieuse, social et médicinale depuis six mille ans. La politique impériale des Etats-Unis répand l’idée selon laquelle la “coca” est “cocaïne” pour combattre les peuples andins et les dépouiller de leurs ressources naturelles. -

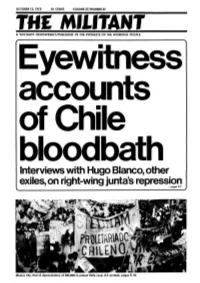

Interviews with Hugo Blanco, Other Exiles, on Right-Wing Junta's Repression · -Pages 5-7

OCTOBER 12, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 37 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE II Interviews with Hugo Blanco, other exiles, on right-wing junta's repression · -pages 5-7 Mexico City. Part of demonstration of 100,000 to protest Chile coup. U.S. protests, pages 9, 10. ln.Briel MICHIGAN STUDENTS OPPOSE TUITION HIKE: Stu in San Francisco last March of the tenth anniversary dents at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are of the CIA-backed coup that brought the shah of Iran THIS organizing a tuition strike to roll back a 24 percent fee to power. hike passed by the board of regents this summer. Widespread protests forced the dropping of the assault WEEK'S The Student Action Committee, which is coordinating charges. But Shokat and Ghaemmagham pleaded guilty the strike, held a rally of 250 students on Sept. 28, despite to the lesser charge of "intimidation" to bring the case MILITANT pouring rain. Militant correspondent Marty Pettit reports to an end. 3 UFW-Teamster talks the protesters then lined up in front of collection windows ·The Iranian Student Association has urged protests 4 Boudin describes gov't in the registration area and successfully prevented cashiers against these sentences, especially the imposition of the from accepting payments. maximum jail term on Shokat. Write to: Honorable Judge attempts to discredit him Strike leader Ruy Teixeira said, "A lot of people see this Williams, Federal Building, Nineteenth Floor, 450 Golden 8 New evidence of mass whole struggle, which hopefully will become nationwide, Gate Ave., San Francisco, <_::alif. -

University of California Santa Cruz Marxism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ MARXISM AND CONSTITUENT POWER IN LATIN AMERICA: THEORY AND HISTORY FROM THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY THROUGH THE PINK TIDE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS with an emphasis in POLITICS by Robert Cavooris December 2019 The dissertation of Robert Cavooris is approved: _______________________________________ Robert Meister, Chair _______________________________________ Guillermo Delgado-P. _______________________________________ Juan Poblete _______________________________________ Megan Thomas _________________________________________ Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Robert Cavooris, 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements and Dedication vi Preface x Introduction 1 Chapter 1 41 Intellectuals and Political Strategy: Hegemony, Posthegemony, and Post-Marxist Theory in Latin America Chapter 2 83 Constituent Power and Capitalism in the Works of René Zavaleta Mercado Chapter 3 137 Bolivian Insurgency and the Early Work of Comuna Chapter 4 204 Potentials and Limitations of the Bolivian ‘Process of Change’ Conclusions 261 Appendix: List of Major Works by Comuna (1999–2011) 266 Bibliography 271 iii Abstract Marxism and Constituent Power in Latin America: Theory and History from the Mid-Twentieth Century through The Pink Tide Robert Cavooris Throughout the history of Marxist theory and practice in Latin America, certain questions recur. What is the relationship between political and social revolution? How can state institutions serve as tools for political change? What is the basis for mass collective political agency? And how can intellectual work contribute to broader emancipatory political movements? Through textual and historical analysis, this dissertation examines how Latin American intellectuals and political actors have reframed and answered these questions in changing historical circumstances. -

Hugo Blanco: "I Was Neither a 'Castroite Guerrilla' Nor a 'Terrorist'"

Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6916 Peru Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV550 - November 2020 - Publication date: Monday 23 November 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" Hugo Blanco lives in Mexico, but he travelled to Europe to meet his new German-born granddaughter. Before that, he wanted to go and see his daughter Carmen in Sweden and it was there that the pandemic took him by surprise. Farik Matuk put us in touch with Carmen Blanco, who kindly asked us to send the questions in writing, because Hugo Blanco "can no longer answer by telephone". Here are the answers to the controversy sparked off by the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo (in English Hugo Blanco, Deep River). Roberto Ochoa: Are you aware of the turmoil caused by the screening of the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo? Hugo Blanco: Yes, I am aware of the turmoil caused in Peru and internationally. And I am also moved by the multiple expressions of solidarity that reach me from several places in Peru and around the world. From those who are leading struggles close to mine, but also from young people who until then did not know of my existence, but who are now interested in my trajectory of struggles. Every day, dozens of solidarity messages reach me and my daughter Carmen by email and other social networks. -

The Organisation Communiste Internationaliste Breaks with Trotskyism

TROTSKYISM VERSUS REVISIONISM A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY VOLUME SIX The Organisation Communiste Internationaliste breaks with Trotskyism NEW PARK PUBLICATIONS TROTSKYISM VERSUS REVISIONISM TROTSKYISM VERSUS REVISIONISM A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY edited by C. Slaughter VOLUME SIX The Organisation Comtnuniste Internationaliste breaks with Trotskyism NEW PARK PUBLICATIONS Pubtiahcd by New Park PuWic«ioMLtd.. ItSTaStomHi* Stmt, London SW4 7UG 1975 Set up, Printed and Bound by Trade Union Labour Distributed in the United States by: Labor Publication! Inc., 13S West 14 Street, New York, New York 10011 ISBN 0 902030 73 6 Printed in Great Britain by New Press (T.U.) 186a Oapham High Street, London SW4 7UG Contents FOREWORD xli CHAPTER ONE: THE BOLIVIAN REVOLUTION AND REVISIONISM Document 1 BoMa: Biter Lessons of Defeat, by Tim WohBorth August 30,1971 2 Document 2 What Happened In BoMa? by QuWermo Lore September 1971 8 Document 3 Statement by the OCI Central Committee, September 19,1971 19 Document 4 Statement by the OCI, the POR and the Organizing Committee of Eastern Europe, October 12,1971 23 CHAPTER TWO: THE SPLIT Document S Statement by the International Committee (Majority), October 24,1971 28 Document 6 Declaration of the Central Committee of the OCI, November 24,1971 45 Document r Statement by the International Committee (Majority), March 1,1972 72 CHAPTER THREE: THE FOURTH WORLD CONFERENCE Document • Report of the Fourth Conference of the International Committee, April 10-15,1972 104 Document 9 Manifesto of the Fourth Conference of the International -

Anti-Capitalism Or Anti-Imperialism? Interwar Authoritarian and Fascist Sources of a Reactionary Ideology: the Case of the Bolivian MNR

Anti-Capitalism or Anti-Imperialism? Interwar Authoritarian and Fascist Sources of A Reactionary Ideology: The Case of the Bolivian MNR Loren Goldner Abstract The following recounts the evolution of the core pre-MNR intelligentsia and future leadership of the movement and its post- 1952 government from anti-Semitic, pro-fascist, pro-Axis ideologues in the mid-1930's to bourgeois nationalists receiving considerable US aid after 1952. The MNR leadership, basically after Stalingrad, began to "reinvent itself" in response to the impending Allied victory, not to mention huge pressure from the U.S. in various forms starting ca. 1942. However much the MNR purged itself of its "out-of-date" philofascism by the time it came to power, I wish to show it in the larger context of the top-down, state-driven corporatism that developed in key Latin American countries in this period, specifically Argentina, Brazil and (in a different way) Mexico through the Cardenas period. The following is a demonstration that, contrary to what contemporary complacent leftist opinion in the West thinks, there is a largely forgotten history of reactionary populist and "anti- imperialist" movements in the underdeveloped world that do not shrink from mobilizing the working class to achieve their goals. This little-remembered background is all the more important for understanding the dynamics of the left-populist governments which have emerged in Latin America since the 1990’s. Introduction The following text is a history and analysis of the fascist and proto- fascist ideologies which shaped the pre-history and early history of the Bolivian MNR (Movimiento Nacional Revolucionario) from 1936 to its seizure of power in 1952. -

Trotskygrad on the Altiplano by Bill Weinberg

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2011 reviews Trotskygrad on the Altiplano By Bill Weinberg a militant (at times, even revolution- ian labor movement (from the 1930s ary) labor movement that aligned through the 1980s) with articles with Leon Trotsky and his Fourth from the left and especially Trotsky- International, and rejected Joseph ist press of the day, in both Bolivia Stalin and his Kremlin successors. In and the United States—rescuing a Bolivia’s Radical Tradition: Permanent wealth of information from falling Revolution in the Andes, S. Sándor John into pre- digital oblivion. The book explores the roots of this exceptional- is illustrated with reproductions of ism. To his credit, he resists the temp- radical art and propaganda as well as tation of mechanistic explanations— period photos. John also offers first- but the answer is pretty clearly rooted hand interviews with veterans of the in sheer oppression. miners’ struggle. Faced with a nasty, brutish, and The POR and the PIR were both short life in the tin mines of the founded in the aftermath of the di- altiplano (chronic silicosis made sastrous Chaco War (1932–5), a for an average lifespan of 40 years), senseless and costly conflict with Bolivia’s miners had little patience Paraguay, in which Bolivia’s old oli- for the Moscow-mandated line of garchic political class lost much “two-stage” revolution, which urged credibility—in John’s words, “the subordination to the “bourgeois- death throes of the ancien régime.” BOLIVIA’s Radical TRADITION: democratic” political process un- More enlightened sectors of this PERMANENT REVOLUTION IN THE til feudalism was dismantled and class subsequently began affecting a ANDES by S. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Maoist’ Group

The Marxist Volume XXI, No. 4 October-December 2005 Anil Biswas ‘Maoism’: An Exercise in Anarchism In recent times, some areas of West Bengal have witnessed activities of the ‘Maoist’ group. The group has tried to draw attention to itself through committing several grisly murders and by triggering some explosions. They are engaged in setting up ‘bases’ in the remote and relatively inaccessible locales of West Bengal that border Bihar-Jharkhand. They seek a foothold in some other districts of the state as well. A section of the corporate media has also been encouraging them, by legitimising the Maoists’ killing of CPI (M) leaders and workers in districts like Bankura, Purulia, and Midnapore west. The CPI (M-L)-People’s War and the Maoist Communist Centre, two groups of the Naxalite persuasion, came together on 21 September 2004 to form a new party, the CPI (Maoist). As with the two erstwhile constituents, the Maoists are active in selected areas of Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, and Jharkhand. Because of the secretive style of their working, their political outlook and activities are largely unknown to the mass of the people. The name of the CPI (Maoist) has been associated with violent acts and spreading terror. Going by their programme and ideological stand, the party is a violent anarchist outfit. Anarchy can cause harm to the democratic struggle and Left movement. The CPI (M) will counter this party politically and ideologically. The CPI (M) formed after a long ideological debate in 1964, and a new Party Programme was adopted. Sectarian and ultra-left adventurist trends arose in the ongoing struggle against revisionism and reformism.