Peru: Two Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian Ecosocialist

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7049 Peru Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist - Features - Publication date: Thursday 22 April 2021 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist "Of course I am an ecosocialist, as are the indigenous peoples even if they do not use that term". Hugo Blanco is one of the figures in the struggle for emancipation in Peru. In the 1960s, he played an important role in the revolutionary mobilization of indigenous peasants against the four-century-old dominant agrarian regime latifundism. During a self-defence action, a policeman was killed; Blanco was sentenced to death. Defended by Amnesty International, Sartre and de Beauvoir, he lived in exile in the 1970s: in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and then, in the aftermath of the coup against Allende, in Sweden. Returning home, he joined the Peasant Confederation and became a member of parliament, then a senator under the colours of Izquierda Unida a coalition of left-wing organizations. At the age of 86, he currently [2021] resides in Sweden, retired from "political life". Last month, during the screening of a documentary tracing his career, the Peruvian far right campaigned against him. This is an interview published in his native country: he looks back on his life as an activist. Tell us about your life: were you a peasant or a student? My mother was a small landowner and my father was a lawyer. He had a brother who was studying at La Plata (in Argentina). -

Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon Christian Calienes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2526 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 CHRISTIAN CALIENES All Rights Reserved ii The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon by Christian Calienes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Inés Miyares Chair of Examining Committee Date Cindi Katz Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Inés Miyares Thomas Angotti Mark Ungar THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Production of Space: Indigenous Resistance Movements in the Peruvian Amazon By Christian Calienes Advisor: Inés Miyares The resistance movement that resulted in the Baguazo in the northern Peruvian Amazon in 2009 was the culmination of a series of social, economic, political and spatial processes that reflected the Peruvian nation’s engagement with global capitalism and democratic consolidation after decades of crippling instability and chaos. -

Ponciano Del Pino H

Dear Agrarian Studies Readers: This paper summarizes the main arguments of two chapters in which memories of the Shining Path’s violence are situated in the framework of longer historical memory and state-making from 1920s to 1960s. Beyond the immediate past, land insecurity and conflict, the politics of articulation, and government as idea, political language and identity, shape people’s memory, as well as the position assumed by the communities in the context of the 1980s violence. The book manuscript I am working on explores memories of violence at different levels: I emphasize the production of silences and secrets as the central dynamic in the production of memory on the Shining Path’s Peru. This immediate past is framed in the longer historical memory, the politics of articulation and state-making. Finally, the historicity of memory and violence is seen in memory places, landscape and nature, insofar as those were not outsiders to the violence. I analyze narratives about the power of the mountains and their present weakness, which seems to be the case in the context of melting ice. The environmental change provides another window into communities’ experience of natural and social vulnerability in the context of the state pressure and expansion throughout the twentieth century. This multilevel subjective, political and historical experience of the highland communities of Ayacucho, Peru, not only shapes local politics and culture but also exposes the relation between the process of nation-state formation and transformation, and of colonialism as a global process of domination, which lies at the heart of twentieth-century politics in Peru and many other countries of Latin America. -

D I a R I O D E S E S I O N

R E P U B L I C A A R G E N T I N A D I A R I O D E S E S I O N E S CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE LA NACION 35ª REUNION – 2ª SESION ORDINARIA DE PRÓRROGA DICIEMBRE 3 DE 2008 PERIODO 126º Presidencia de los señores diputados Eduardo A. Fellner, Patricia Vaca Narvaja y Liliana A. Bayonzo Secretarios: Doctor Enrique R. Hidalgo, doctor Ricardo J. Vázquez y don Jorge A. Ocampos Prosecretarios: Doña Marta A. Luchetta, doctor Andrés D. Eleit e ingeniero Eduardo Santín 2 CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE LA NACION Reunión 35ª DIPUTADOS PRESENTES: DELICH, Francisco José LUSQUIÑOS, Luis Bernardo ACOSTA, María Julia DEPETRI, Edgardo Fernando MACALUSE, Eduardo Gabriel ACUÑA, Hugo Rodolfo DI TULLIO, Juliana MARCONATO, Gustavo Ángel AGUAD, Oscar Raúl DÍAZ BANCALARI, José María MARINO, Adriana del Carmen AGUIRRE de SORIA, Hilda Clelia DÍAZ ROIG, Juan Carlos MARTIARENA, Mario Humberto ALBARRACÍN, Jorge Luis DIEZ, María Inés MARTÍN, María Elena ALBRISI, César Alfredo DONDA PÉREZ, Victoria Analía MARTÍNEZ GARBINO, Emilio Raúl ALCUAZ, Horacio Alberto DOVENA, Miguel Dante MARTÍNEZ ODDONE, Heriberto Agustín ALFARO, Germán Enrique ERRO, Norberto Pedro M ASSEI, Oscar Ermelindo ÁLVAREZ, Juan José FABRIS, Luciano Rafael MERCHÁN, Paula Cecilia ALVARO, Héctor Jorge FADEL, Patricia Susana MERLO, Mario Raúl AMENTA, Marcelo Eduardo FEIN, Mónica Haydé MONTERO, Laura Gisela ARBO, José Ameghino FELLNER, Eduardo Alfredo MORÁN, Juan Carlos ARDID, Mario Rolando FERNÁNDEZ BASUALDO, Luis María MORANDINI, Norma Elena ARETA, María Josefa FERNÁNDEZ, Marcelo Omar MORANTE, Antonio Orlando María -

Redalyc.Koka Mama

Argumentos ISSN: 0187-5795 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco México Blanco, Hugo Koka Mama Argumentos, vol. 19, núm. 50, enero-abril, 2006, pp. 117-140 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59501906 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MUNDO ANDINO: HISTORIA, CULTURA Y REBELIÓN DOSSIER KOKA MAMA Hugo Blanco* La “coca” es un emblema de la antigua cultura andina: es la hoja sagrada. Tiene un signifi- cado religioso, social y medicinal desde hace seis mil años. La política imperial de Estados Unidos difunde la idea según la cual “coca es igual a cocaína” para combatir a los pueblos andinos y despojarlos de sus riquezas naturales. KOKA MAMA The “coca” is a symbol of the ancient Andean culture: it is the sacred leaf. It has had a religious, social and medical meaning for more than six thousand years. The imperial policy of the United States disseminates the idea that “coca” and cocaine are the same thing, to attack the Andean villages and deprive them from their natural resources. KOKA MAMA La “coca” est un emblème de l’ancienne culture andine : elle est feuille sacrée. La “coca” a une signification religieuse, social et médicinale depuis six mille ans. La politique impériale des Etats-Unis répand l’idée selon laquelle la “coca” est “cocaïne” pour combattre les peuples andins et les dépouiller de leurs ressources naturelles. -

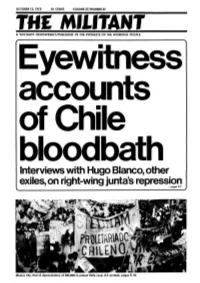

Interviews with Hugo Blanco, Other Exiles, on Right-Wing Junta's Repression · -Pages 5-7

OCTOBER 12, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 37 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE II Interviews with Hugo Blanco, other exiles, on right-wing junta's repression · -pages 5-7 Mexico City. Part of demonstration of 100,000 to protest Chile coup. U.S. protests, pages 9, 10. ln.Briel MICHIGAN STUDENTS OPPOSE TUITION HIKE: Stu in San Francisco last March of the tenth anniversary dents at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are of the CIA-backed coup that brought the shah of Iran THIS organizing a tuition strike to roll back a 24 percent fee to power. hike passed by the board of regents this summer. Widespread protests forced the dropping of the assault WEEK'S The Student Action Committee, which is coordinating charges. But Shokat and Ghaemmagham pleaded guilty the strike, held a rally of 250 students on Sept. 28, despite to the lesser charge of "intimidation" to bring the case MILITANT pouring rain. Militant correspondent Marty Pettit reports to an end. 3 UFW-Teamster talks the protesters then lined up in front of collection windows ·The Iranian Student Association has urged protests 4 Boudin describes gov't in the registration area and successfully prevented cashiers against these sentences, especially the imposition of the from accepting payments. maximum jail term on Shokat. Write to: Honorable Judge attempts to discredit him Strike leader Ruy Teixeira said, "A lot of people see this Williams, Federal Building, Nineteenth Floor, 450 Golden 8 New evidence of mass whole struggle, which hopefully will become nationwide, Gate Ave., San Francisco, <_::alif. -

Hugo Blanco: "I Was Neither a 'Castroite Guerrilla' Nor a 'Terrorist'"

Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6916 Peru Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV550 - November 2020 - Publication date: Monday 23 November 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" Hugo Blanco lives in Mexico, but he travelled to Europe to meet his new German-born granddaughter. Before that, he wanted to go and see his daughter Carmen in Sweden and it was there that the pandemic took him by surprise. Farik Matuk put us in touch with Carmen Blanco, who kindly asked us to send the questions in writing, because Hugo Blanco "can no longer answer by telephone". Here are the answers to the controversy sparked off by the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo (in English Hugo Blanco, Deep River). Roberto Ochoa: Are you aware of the turmoil caused by the screening of the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo? Hugo Blanco: Yes, I am aware of the turmoil caused in Peru and internationally. And I am also moved by the multiple expressions of solidarity that reach me from several places in Peru and around the world. From those who are leading struggles close to mine, but also from young people who until then did not know of my existence, but who are now interested in my trajectory of struggles. Every day, dozens of solidarity messages reach me and my daughter Carmen by email and other social networks. -

Marx & Philosophy Review of Books » 2015 » Gaido: Che Wants to See You Ciro Roberto Bustos Che Wants to See You: the Untol

Marx & Philosophy Review of Books » 2015 » Gaido: Che Wants to See You Ciro Roberto Bustos Che Wants to See You: The Untold Story of Che in Bolivia Verso, London, 2013. 468pp., £25 hb ISBN 9781781680964 Reviewed by Daniel Gaido Comment on this review About the reviewer Daniel Gaido Daniel Gaido is a researcher at the National Research Council (Conicet), Argentina. He is author of The Formative Period of American Capitalism (Routledge, 2006) and co-editor, with Richard Day, of Witnesses to Permanent Revolution (Brill, 2009), Discovering Imperialism (Brill, 2009) and Responses to Marx's 'Capital' (Brill, forthcoming). More... Review The publication of these memoirs by one of Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s key men in Argentina and Bolivia is a major political and literary achievement. Politically, not because it shows the superiority of Che’s rural armed foco strategy and his peasant way to socialism over Marx’s strategy of building a revolutionary working-class political party, but because it provides a truthful account of Che’s guerrillas exploits, and in that sense it is the best homage that could have been paid to his memory. Artistically, because Bustos’ unique experiences are rendered in a lively and captivating style, which makes the reading of these at times brutal and traumatizing reminiscences an enjoyable experience. Ciro Bustos was born in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1932. A painter by profession, he studied at the School of Fine Arts of the National University of Cuyo, Mendoza. Attracted by the Cuban Revolution, in 1961 he travelled to Havana, where he met Che, who included him in the group he chose to carry out his revolutionary project in Argentina – part of Che’s wider “continental plan” to set up a guerrilla base in Northern Argentina and Southern Bolivia and Peru. -

El Período Histórico 1955 / 1976, Su Influencia En La Juventud De

Cuando se planteó la posibilidad de crear una página Web de homenaje a los compañeros Marplatenses desaparecidos del PST y la JSA, se concluyó que todas sus trayectorias era en cierto modo convergentes, a la vez que todos nosotros habíamos sido influenciados por el mismo entorno, que no era otro que aquel en el que vivimos. Pero si hay algo sobre lo que no hubo ninguna duda, fue que el punto de partida de nuestra historia y la de la mayoría de los 30.000 desaparecidos, era el último gobierno de Perón. El objetivo no es otro que sintetizar el período que va de mediados de los 50 hasta el golpe militar de 1976, utilizando como fuente fundamental de información la enciclopedia Wikipedia con sus enlaces. Al final de este resumen también se realiza una pequeña exposición de los acontecimientos acaecidos en la ciudad de Mar del Plata, a partir del asesinato de Silvia Filler, hecho este que propició “El Marplatazo”. Utilizando como fuente el libro de Carlos Bozzi “Luna Roja” se resume la espiral de violencia que se produjo en “La Ciudad Feliz” por el accionar de elementos de extrema derecha y paramilitares cuyo objetivo era anular la influencia, en el movimiento estudiantil y obrero, de las organizaciones de izquierda, contestando a su vez a las acciones, en su mayoría testimoniales, de los grupos guerrilleros, que alcanzaron su punto álgido con el asesinato del abogado Ernesto Piantoni, dirigente de la CNU. Un repaso a esa parte de la “Historia de Argentina”, que está a final del libro. Fuente mayoritaria: Wikipedia. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Envío Incluido En Exploración

OSVALDO por otras voces BAYER Segunda edición, corregida y ampliada OSVALDO por otras voces BAYER Segunga edición, corregida y ampliada Julio Ferrer (coordinador) Ferrer, Julio Osvaldo Bayer por otras voces / Julio Ferrer; compilado por Julio Ferrer. - 2.º ed. - La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata, 2011. 220 p. ; 21x16 cm. ISBN 978-950-34-0710-3 1. Entrevistas. 2. Osvaldo Bayer. I. Ferrer, Julio, comp. II. Título. CDD 070.4 OSVALDO BAYER por otras voces Segunda edición, corregida y ampliada Julio Ferrer (coordinador) Coordinación Editorial: Anabel Manasanch Corrección: María Eugenia López, María Virginia Fuente, Magdalena Sanguinetti y Marisa Schieda. Diseño y diagramación: Andrea López Osornio Imagen de tapa: REP Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata (Edulp) Calle 47 Nº 380 / La Plata B1900AJP / Buenos Aires, Argentina +54 221 427 3992 / 427 4898 [email protected] www.editorial.unlp.edu.ar Edulp integra la Red de Editoriales Universitarias (REUN) Segunda edición, 2011 ISBN N.º 978-950-34-0710-3 Queda hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 © 2011 - Edulp Impreso en Argentina A mi querida y bella hija Micaela Agradecimientos Agradezco profundamente a todos los hombres y mujeres de la cultura por su valioso y desinteresado aporte, que ha permitido el nacimiento de este libro. A la gente de la Editorial de la Universidad de La Plata: Julito, Mónica, Sebas- tián, María Inés, Ulises, por los buenos momentos. A su director, Leonardo González, por creer que este libro merecía volver a editarse. A Miguel Rep, por la generosa -

THE PEASANTS AS a REVOLUTIONARY CLASS: an Early Latin American View

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Government and International Affairs Faculty Government and International Affairs Publications 5-1-1978 The eP asants as a Revolutionary Class: An Early Latin American View Harry E. Vanden University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gia_facpub Part of the Government Contracts Commons, and the International Relations Commons Scholar Commons Citation Vanden, Harry E., "The eP asants as a Revolutionary Class: An Early Latin American View" (1978). Government and International Affairs Faculty Publications. 93. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gia_facpub/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Government and International Affairs at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government and International Affairs Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARRY E. VANDEN Department of Political Science University of South Florida Tampa, Florida 33620 THE PEASANTS AS A REVOLUTIONARY CLASS: An Early Latin American View We do not regard Marx's theory as something completed and inviolable; on the contrary, we are convinced that it has only laid the foundation stone of the science which socialists must develop in all directions if they wish to keep pace with life. V. I. Lenin (Our Program) The peasant is one of the least understood and most abused actors on the modern political stage. He is maligned for his political passivity and distrust of national political movements. Yet, most of the great twentieth-century revolutions in the Third World have, according to most scholars, been peasant based (Landsberger, 1973: ix; Wolf, 1969).