Ponciano Del Pino H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lima Junin Pasco Ica Ancash Huanuco Huancavelica Callao Callao Huanuco Cerro De Pasco

/" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" 78C°U0E'0N"WCA DEL RÍO CULEBRAS 77°0'0"W 76°0'0"W CUENCA DEL RÍO ALTO MARAÑON HUANUCO Colombia CUENCA DEL RÍO HUARMEY /" Ecuador CUENCA DEL RÍO SANTA 10°0'0"S 10°0'0"S TUMBES LORETO HUANUCO PIURA AMAZONAS Brasil LAMBAYEQUECAJAMARCA ANCASH SAN MARTIN LA LICBEURTAED NCA DEL RÍO PACHITEA CUENCA DEL RÍO FORTALEZA ANCASH Peru HUANUCO UCAYALI PASCO COPA ") JUNIN CALLAOLIMA CUENCA DEL RÍO PATIVILCA CUENCA DEL RÍO ALTO HUALLAGA MADRE DE DIOS CAJATAMBO HUANCAVELICA ") CUSCO AYACUCHOAPURIMAC ICA PUNO HUANCAPON ") Bolivia MANAS ") AREQUIPA GORGOR ") MOQUEGUA OYON PARAMONGA ") CERRO DE PASCOPASCO ") PATIVILCA TACNA ") /" Ubicación de la Región Lima BARRANCA AMBAR Chile ") ") SUPE PUERTOSUPE ANDAJES ") ") CAUJUL") PACHANGARA ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO SUPE NAVAN ") COCHAMARCA ") CUENCA DEL R")ÍO HUAURA ") ")PACCHO SANTA LEONOR 11°0'0"S VEGUETA 11°0'0"S ") LEONCIO PRADO HUAURA ") CUENCA DEL RÍO PERENE ") HUALM")AY ") H")UACHO CALETA DE CARQUIN") SANTA MARIA SAYAN ") PACARAOS IHUARI VEINTISIETE DE NOVIEMBR")E N ") ") ")STA.CRUZ DE ANDAMARCA LAMPIAN ATAVILLOS ALTO ") ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO CHANCAY - HUARAL ATAVILLOS BAJO ") SUMBILCA HUAROS ") ") CANTA JUNIN ") HUARAL HUAMANTANGA ") ") ") SAN BUENAVENTURA LACHAQUI AUCALLAMA ") CHANCAY") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO MANTARO CUENCA DEL RÍO CH")ILLON ARAHUAY LA")R")AOS ") CARAMPOMAHUANZA STA.ROSA DE QUIVES ") ") CHICLA HUACHUPAMPA ") ") SAN ANTONIO ") SAN PEDRO DE CASTA SAN MATEO ANCON ") ") ") SANTA ROSA ") LIMA ") PUENTE PIEDRACARABAYLLO MATUCANA ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO RIMAC ") SAN MATEO DE OTAO -

Relación De Agencias Que Atenderán De Lunes a Viernes De 8:30 A. M. a 5:30 P

Relación de Agencias que atenderán de lunes a viernes de 8:30 a. m. a 5:30 p. m. y sábados de 9 a. m. a 1 p. m. (con excepción de la Ag. Desaguadero, que no atiende sábados) DPTO. PROVINCIA DISTRITO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN Avenida Luzuriaga N° 669 - 673 Mz. A Conjunto Comercial Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Lote 09 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Avenida José Gálvez N° 245-250 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Calle Nicolás de Piérola N°110 -112 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Rivero Calle Rivero N° 107 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Periférica Arequipa Avenida Cayma N° 618 Arequipa Arequipa José Luis Bustamante y Rivero Bustamante y Rivero Avenida Daniel Alcides Carrión N° 217A-217B Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Avenida Mariscal Castilla N° 618 Arequipa Camaná Camaná Camaná Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 (Boulevard) Ayacucho Huamanga Ayacucho Ayacucho Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Jirón Pisagua N° 552 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Esquina Avenida El Sol con Almagro s/n Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Avenida Tomasa Ttito Condemaita 1207 Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Jirón Francisco de Angulo 286 Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Jirón 28 de Julio N° 1061 Huánuco Leoncio Prado Rupa Rupa Tingo María Avenida Antonio Raymondi N° 179 Ica Chincha Chincha Alta Chincha Jirón Mariscal Sucre N° 141 Ica Ica Ica Ica Avenida Graú N° 161 Ica Pisco Pisco Pisco Calle San Francisco N° 155-161-167 Junín Huancayo Chilca Chilca Avenida 9 De Diciembre N° 590 Junín Huancayo El Tambo Huancayo Jirón Santiago Norero N° 462 Junín Huancayo Huancayo Periférica Huancayo Calle Real N° 517 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Trujillo Avenida Diego de Almagro N° 297 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Periférica Trujillo Avenida Manuel Vera Enríquez N° 476-480 Avenida Victor Larco Herrera N° 1243 Urbanización La La Libertad Trujillo Victor Larco Herrera Victor Larco Merced Lambayeque Chiclayo Chiclayo Chiclayo Esquina Elías Aguirre con L. -

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian Ecosocialist

Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article7049 Peru Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist - Features - Publication date: Thursday 22 April 2021 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco, the Peruvian ecosocialist "Of course I am an ecosocialist, as are the indigenous peoples even if they do not use that term". Hugo Blanco is one of the figures in the struggle for emancipation in Peru. In the 1960s, he played an important role in the revolutionary mobilization of indigenous peasants against the four-century-old dominant agrarian regime latifundism. During a self-defence action, a policeman was killed; Blanco was sentenced to death. Defended by Amnesty International, Sartre and de Beauvoir, he lived in exile in the 1970s: in Mexico, Argentina, Chile and then, in the aftermath of the coup against Allende, in Sweden. Returning home, he joined the Peasant Confederation and became a member of parliament, then a senator under the colours of Izquierda Unida a coalition of left-wing organizations. At the age of 86, he currently [2021] resides in Sweden, retired from "political life". Last month, during the screening of a documentary tracing his career, the Peruvian far right campaigned against him. This is an interview published in his native country: he looks back on his life as an activist. Tell us about your life: were you a peasant or a student? My mother was a small landowner and my father was a lawyer. He had a brother who was studying at La Plata (in Argentina). -

Jr. Callao Nº 122 – Ayacucho

Jr. Callao Nº 122 – Ayacucho PRESENTACION El Gobernador del Gobierno Regional de Ayacucho, en el marco de su política de una gestión transparente, se complace en presentar a la II Audiencia Pública Regional 2019, y a la comunidad ayacuchana, los resultados de la gestión institucional correspondiente al periodo enero-diciembre 2019, donde se muestra los avances más importantes de las actividades programadas por la Sede Central, las Direcciones Regionales Sectoriales y las Oficinas Sub Regionales. Las actividades durante este año se han orientado a dar continuidad a los proyectos ejecutados en el ejercicio fiscal 2018, en el marco de los lineamientos de gestión establecidos en el Plan Estratégico Institucional 2018-2020, dando prioridad a aquéllos que tienen importancia estratégica para el desarrollo regional. En tal sentido, los avances mostrados en el presente informe están en el marco del Plan Operativo Institucional 2019 y la Política Regional de Gobierno, a fin de orientar las intervenciones del Gobierno Regional a la mejora de la calidad de vida de la población. Para mayor detalle, dichos avances se muestran por cada Gerencia Regional y Dirección Regional Sectorial. Una de las políticas de la nueva gestión que me honro en presidir es la transparencia y libre acceso a la información sobre la gestión regional, el cual es coherente con el proceso de modernización de la gestión pública. Y una de las formas de mostrar esta transparencia es informando a la comunidad sobre los avances de la gestión, así como sobre los problemas que se viene enfrentando. En consecuencia, dejamos a vuestra consideración los resultados de la gestión frente al Gobierno Regional de Ayacucho. -

The Documentation of Quinoa Ceramics, a Traditional Art of Ayacucho, Peru

Title: The documentation of Quinoa Ceramics, a traditional art of Ayacucho, Peru. 1. Introduction Documenting a cultural expression of a traditional art developed since the Pre Hispanic Period in Peru in a place where the people, geography and architecture have not changed so much in time because of centralism of policies in the country-, was a challenge for us. Most of the information we looked for about Quinoa Ceramics was not in books, so we had to look deeper to find important data to register, analyze and systematize in order to document a tangible expression of an intangible heritage that is at the same time antique and contemporary, traditional and modern. This work was even harder if we consider that all the information rested not only in people but also in nature. In general, the cultures of the Andean regions in Peru are very connected with their environment so most of their raw material is directly extracted from the natural environment with a deep sense of respect and mutual need, without affecting the natural balance in their world. Talking about Quinoa Ceramics, we had to go to the mountains were the colored earth was extracted to be used as a pigment of their work, following a long walking route, to find the earth quarries locals usually visit. The landscape we found was really incredible. Speaking with the artisans (or artists, or masters, as they are known in the town) was also a great experience of learning about their cultural worldview of everything. This process was very important to understand the social context of the Quinoa Ceramics. -

Lima, Arequipa, Junín, Ayacucho Y Puno: Regiones Con Mayores Índices De Feminicidio

Lima, Arequipa, Junín, Ayacucho y Puno: regiones con mayores índices de feminicidio Más de mil casos de feminicidio se registraron en el Perú en los últimos ocho años, según el Informe de Adjuntía de la Defensoría del Pueblo: “Violencia contra las Mujeres: perspectivas de las víctimas, obstáculos e índices cuantitativos”, que recoge información de las regiones Áncash, Arequipa, Ayacucho, Cusco, Huánuco, Junín, Lambayeque, La Libertad, Lima y Puno. De acuerdo al reporte, elaborado por la Adjuntía para la Mujer de nuestra institución y presentado ayer en la ciudad de Puno, en nuestro país ocurrieron 1003 hechos calificados como feminicidio entre los años 2009 y 2017, mientras que la cifra de tentativas por ese delito en el mismo periodo asciende a 1308 casos. Lima es la región que registra la mayor cantidad de feminicidios, con 382 casos. Le siguen Arequipa, Junín y Ayacucho, mientras que la región altiplánica ocupa el quinto lugar, con 50 muertes de mujeres entre los años 2009 y 2017. En lo referido a violencia contra las mujeres, los Centros Emergencia Mujer identificaron más de 40 mil casos en los primeros cuatro meses de este año, siendo Lima, Arequipa, Cusco, Junín, La Libertad y Puno las regiones con los más altos índices. La presentación del informe se realizó ante la asistencia de más de 130 personas, entre autoridades, funcionarios, servidores públicos del Ministerio Público y de la Instancia Provincial de Concertación para Prevenir, Sancionar y Erradicar la Violencia contra la Mujer así como representantes de la sociedad civil. Durante el evento, se informó que frente a esta realidad, la Defensoría del Pueblo viene desarrollando Audiencias Defensoriales en nueve regiones del país, en las que se recoge los aportes de la población para enfrentar el problema de la violencia hacia niñas y mujeres. -

Agricultural and Mining Labor Interactions in Peru: a Long-Run Perspective

Agricultural and Mining Labor Interactions in Peru: ALong-RunPerspective(1571-1812) Apsara Iyer1 April 4, 2016 1Submitted for consideration of B.A. Economics and Mathematics, Yale College Class of 2016. Advisor: Christopher Udry Abstract This essay evaluates the context and persistence of extractive colonial policies in Peru on contemporary development indicators and political attitudes. Using the 1571 Toledan Reforms—which implemented a system of draft labor and reg- ularized tribute collection—as a point of departure, I build a unique dataset of annual tribute records for 160 districts in the Cuzco, Huamanga, Huancavelica, and Castrovirreyna regions of Peru over the years of 1571 to 1812. Pairing this source with detailed historic micro data on population, wages, and regional agri- cultural prices, I develop a historic model for the annual province-level output. The model’s key parameters determine the output elasticities of labor and capital and pre-tribute production. This approach allows for an conceptual understand- ing of the interaction between mita assignment and production factors over time. Ithenevaluatecontemporaryoutcomesofagriculturalproductionandpolitical participation in the same Peruvian provinces, based on whether or not a province was assigned to the mita. I find that assigning districts to the mita lowers the average amount of land cultivated, per capita earnings, and trust in municipal government Introduction For nearly 250 years, the Peruvian economy was governed by a rigid system of state tribute collection and forced labor. Though the interaction between historical ex- traction and economic development has been studied in a variety of post-colonial contexts, Peru’s case is unique due to the distinct administration of these tribute and labor laws. -

Redalyc.Koka Mama

Argumentos ISSN: 0187-5795 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco México Blanco, Hugo Koka Mama Argumentos, vol. 19, núm. 50, enero-abril, 2006, pp. 117-140 Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Unidad Xochimilco Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=59501906 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MUNDO ANDINO: HISTORIA, CULTURA Y REBELIÓN DOSSIER KOKA MAMA Hugo Blanco* La “coca” es un emblema de la antigua cultura andina: es la hoja sagrada. Tiene un signifi- cado religioso, social y medicinal desde hace seis mil años. La política imperial de Estados Unidos difunde la idea según la cual “coca es igual a cocaína” para combatir a los pueblos andinos y despojarlos de sus riquezas naturales. KOKA MAMA The “coca” is a symbol of the ancient Andean culture: it is the sacred leaf. It has had a religious, social and medical meaning for more than six thousand years. The imperial policy of the United States disseminates the idea that “coca” and cocaine are the same thing, to attack the Andean villages and deprive them from their natural resources. KOKA MAMA La “coca” est un emblème de l’ancienne culture andine : elle est feuille sacrée. La “coca” a une signification religieuse, social et médicinale depuis six mille ans. La politique impériale des Etats-Unis répand l’idée selon laquelle la “coca” est “cocaïne” pour combattre les peuples andins et les dépouiller de leurs ressources naturelles. -

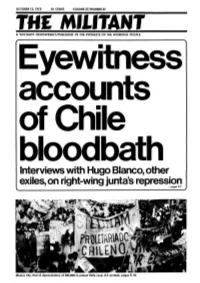

Interviews with Hugo Blanco, Other Exiles, on Right-Wing Junta's Repression · -Pages 5-7

OCTOBER 12, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 37 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE II Interviews with Hugo Blanco, other exiles, on right-wing junta's repression · -pages 5-7 Mexico City. Part of demonstration of 100,000 to protest Chile coup. U.S. protests, pages 9, 10. ln.Briel MICHIGAN STUDENTS OPPOSE TUITION HIKE: Stu in San Francisco last March of the tenth anniversary dents at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are of the CIA-backed coup that brought the shah of Iran THIS organizing a tuition strike to roll back a 24 percent fee to power. hike passed by the board of regents this summer. Widespread protests forced the dropping of the assault WEEK'S The Student Action Committee, which is coordinating charges. But Shokat and Ghaemmagham pleaded guilty the strike, held a rally of 250 students on Sept. 28, despite to the lesser charge of "intimidation" to bring the case MILITANT pouring rain. Militant correspondent Marty Pettit reports to an end. 3 UFW-Teamster talks the protesters then lined up in front of collection windows ·The Iranian Student Association has urged protests 4 Boudin describes gov't in the registration area and successfully prevented cashiers against these sentences, especially the imposition of the from accepting payments. maximum jail term on Shokat. Write to: Honorable Judge attempts to discredit him Strike leader Ruy Teixeira said, "A lot of people see this Williams, Federal Building, Nineteenth Floor, 450 Golden 8 New evidence of mass whole struggle, which hopefully will become nationwide, Gate Ave., San Francisco, <_::alif. -

THE WARI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, PERU Course ID: ARCH 315B June 16 – July 15, 2018 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTORS: Dr

THE WARI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT, PERU Course ID: ARCH 315B June 16 – July 15, 2018 FIELD SCHOOL DIRECTORS: Dr. José Ochatoma ([email protected]) Prof. Marta Cabrera ([email protected]) Danielle Kurin ([email protected]) INTRODUCTION The Huari Empire (ca. 600—1000 A.D.) is arguably the most enigmatic complex civilization to have ever existed. One of the earliest, most extensive, and powerful societies in the world, Huari emerged in an arid, rugged region of the Peruvian Andes called Ayacucho, an area that had no prior high cultural development, nor the benefits of an immense population, great wealth and abundant natural resources. Given these challenges, how did Huari become the first expansive civilization of the New World? The answer may be found in the sprawling, unexplored ruins of Wari, its eponymous capital city. The city of Wari was one of the largest, most populous settlements in the ancient Americas. It is an immense urban metropolis, subdivided by imposing stone barricades into distinct neighborhoods, or districts. Wari’s walls—up to 12 meters high and two meters wide—enclosed dozens of honey-comb-like neighborhoods. Like other capital cities, Wari’s districts appeared over time and followed common construction patterns including multi-storied buildings built atop man- made platform mounds. These architectural complexes housed a labyrinth of courtyards, circuitous corridors, and cubicle-like rooms. Huge reservoirs fed a complex network of stone aqueducts, providing 1 | P a g e fresh, running water to those dwelling therein. In its heyday, 50,000 people lived in this crowded, multiethnic city. Administratively, Wari was the epicenter of power, controlling all aspects of religious, civilian, economic, and military life. -

American Indian Culture and Economic Development in the Twentieth Century

Native Pathways EDITED BY Brian Hosmer AND Colleen O’Neill FOREWORD BY Donald L. Fixico Native Pathways American Indian Culture and Economic Development in the Twentieth Century University Press of Colorado © 2004 by the University Press of Colorado Published by the University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Native pathways : American Indian culture and economic development in the twentieth century / edited by Brian Hosmer and Colleen O’Neill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87081-774-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87081-775-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Economic conditions. 2. Indian business enterprises— North America. 3. Economic development—North America. 4. Gambling on Indian reservations—North America. 5. Oil and gas leases—North America. 6. North America Economic policy. 7. North America—Economic conditions. I. Hosmer, Brian C., 1960– II. O’Neill, Colleen M., 1961– E98.E2N38 2004 330.973'089'97—dc22 2004012102 Design by Daniel Pratt 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents DONALD L. -

Hugo Blanco: "I Was Neither a 'Castroite Guerrilla' Nor a 'Terrorist'"

Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article6916 Peru Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" - IV Online magazine - 2020 - IV550 - November 2020 - Publication date: Monday 23 November 2020 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/8 Hugo Blanco: "I was neither a 'Castroite guerrilla' nor a 'terrorist'" Hugo Blanco lives in Mexico, but he travelled to Europe to meet his new German-born granddaughter. Before that, he wanted to go and see his daughter Carmen in Sweden and it was there that the pandemic took him by surprise. Farik Matuk put us in touch with Carmen Blanco, who kindly asked us to send the questions in writing, because Hugo Blanco "can no longer answer by telephone". Here are the answers to the controversy sparked off by the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo (in English Hugo Blanco, Deep River). Roberto Ochoa: Are you aware of the turmoil caused by the screening of the documentary Hugo Blanco, Río Profundo? Hugo Blanco: Yes, I am aware of the turmoil caused in Peru and internationally. And I am also moved by the multiple expressions of solidarity that reach me from several places in Peru and around the world. From those who are leading struggles close to mine, but also from young people who until then did not know of my existence, but who are now interested in my trajectory of struggles. Every day, dozens of solidarity messages reach me and my daughter Carmen by email and other social networks.