Developing a Volunteer Program Toolbox for South African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36261 22-3 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol. 573 Pretoria, 22 2013 Maart No. 36261 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 301221—A 36261—1 2 No. 36261 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 22 MARCH 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande -

Western Cape Education Department

WESTERN CAPE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT CRITERIA FOR THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE (NSC) AWARDS FOR 2011 AWARDS TO SCHOOLS CATEGORY 1 - EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE In this category, awards are made to the top twenty schools in the province (including independent schools) that have achieved excellence in academic results in 2011, based on the following criteria: (a) Consistency in number of grade 12 candidates over a period of 3 years (at least 90%) of previous years (b) an overall pass rate of at least 95% in 2011 (c) % of candidates with access to Bachelor’s degree (d) % of candidates with Mathematics passes Each school will receive an award of R15 000 for the purchase of teaching and learning support material. CATEGORY 1: EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE No SCHOOL NAME 1. Rustenburg High School for Girls’ 2. Herschel Girls School 3. Diocesan College 4. Herzlia High School 5. Rondebosch Boys’ High School 6. Westerford High School 7. Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 8. South African College High School 9. Centre of Science and Technology 10. Paul Roos Gimnasium 11. York High School 12. Stellenberg High School 13. Wynberg Boys’ High School 14. Paarl Gimnasium 15. The Settlers High School 16. Hoër Meisieskool La Rochelle 17. Hoërskool Durbanville 18. Hoërskool Vredendal 19. Stellenbosch High School 20. Hoërskool Overberg 21. South Peninsula High School 22. Norman Henshilwood High School 2 CATEGORY 2 - MOST IMPROVED SCHOOLS Category 2a: Most improved Public Schools Awards will be made to schools that have shown the greatest improvement in the numbers that pass over the period 2009-2011. Improvement is measured in terms of the numbers passing. -

Newsletter-9-17.Pdf

30 March2017 Dear Parent/Guardian NEWSLETTER 9/17 We have reached the end of a highly successful term. So much has been achieved and we have big dreams and plans for the remainder of the year. Allow me this opportunity to thank every dedicated educator, coach and learner for their hard work and commitment. It is wonderful to see the scale of participation and the level at which we are competing now. Sport and culture have gone from strength to strength. Add to that the excellent academic results we attained last year, and you have to agree that our school is blessed with exceptional learners, educators and parents. During a recent visit by the Curro Transformation and Diversity team, we were complimented on the friendliness of our learners and staff. They noticed how learners went out of their way to greet them and to assist where they could. We also often get compliments from visitors, who work with our learners, regarding their ability to think out of the box and come up with new ideas and solutions. Schools close on Friday, 31 March at 11:00. Reports will be issued to learners on this day. Term 2 starts on Wednesday, 19 April. Educators already start on Tuesday, 18 April. Enjoy a well-deserved break with your children. May God keep you safe and may you experience a blessed Easter. STAFF MATTERS We wish to congratulate Mr Christiaan Botha who attended the North-West University of Potchefstroom’s graduation ceremony to receive his Bachelor’s Degree in Education (BEd). Congratulations to Mrs Mariëtte Viljoen whose daughter, Obie, had a baby girl earlier this week. -

Angelo Davids Ons 1Ste Blitzbok!

Stellenberg Stellenberg High School Newsletter 3/2019 March/April IN THIS ISSUE Stellies got Talent • 6 • Swimming • 16 • Angelo Davids Hokkie • 18 • Ons 1ste Blitzbok! 2 Stellenberg High School Newsletter • March/April 2019 Erekleure Baie geluk aan die volgende leerders wat op 7 Mei 2019 hulle erekleure of junior-kleure ontvang: Landloop Tennis Basketball René Steyn Gideon Anderson Thina Campbell Pieter Fourie Atletiek Nèo Sauls Gymnastics Javier Davids Hanell Fourie Chaney van Niekerk Dejean Tolmie Jhoané Jonker Hanrike de Bruyne Taneeka Carstens Lianke Potgieter MMA Anja Esterhuysen Reece Frye Wessel Joubert Wentzel Kriek Nadia Olsen Tweekamp Emma Arendse Amica Nieuwoudt Stefani du Plessis Nadia Olsen KULTUUR Nicola Middleton Brendan Oosthuizen René Steyn Walter de Jongh Public Speaking Liska Cilliers Nicke van Rensburg Suané Vorster Francois Joubert Daleen Laurence Jenna van der Watt Ingeborg Louw Anita van Niekerk Ténica Mearns Retief Ochse Musiek Niel Nelson Thomas Fowler Philip Marais Gabrielle Lazarus (Hoogste Jaco Wolstenholme Marné de Wet Toekenning) Elzahn Swanepoel Bianca van der Vyver Skaak Andrea van der Merwe Petrie de Wit Courtney van Heerden Helandi van der Merwe Danté Eaton (Hoogste Toekenning) Jean-Jacques van Schalkwyk Stefani du Plessis Emil Schnabel Emma Thom Stephan de Wit Gholf Suané Vorster Jemma Louw Luke Hay Courtney Hiscock Reece Frye Swem Nicolene Smuts Juan Boshoff Marethe Honey Kiaan Terblanche Jaco Wolstenholme Brendan Oosthuizen BUITE SPORT Walter de Jongh Action Netball BUITE KULTUUR Tania Nel Mika Lourens Lené Coetzee Koor Ténica Mearns Luhani Engelbrecht Hip Hop Shuné van Zyl Duits-Olimpiadewenner Baie geluk aan Celeste Calitz wat saam met haar klasmaats verlede Oktober aan die olimpiade deelgeneem het en eerste in die land is! Nou wag ons om te hoor wanneer sy haar Duitslandreisprys gaan onderneem. -

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards for 2017

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards For 2017 Awards to learners Learners Will Receive Awards For Excellence In Subject Performance, Excellence Despite Barriers To Learning, Special Ministerial Awards And For The Top 50 Positions In The Province. All Learners Will Receive A Monetary Award And A Certificate. Category : Learner Subject Awards In This Category, One Award Is Handed To The Candidate With The Highest Mark In The Designated Subjects. Each Learner Will Receive R 6 000 And A Certificate. Subject Description Name Centre Name Final Mark Accounting Kiran Rashid Abbas Herschel Girls School 300 Accounting Rita Elise Van Der Walt Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 300 Accounting Philip Visage Hugenote Hoërskool 300 Afrikaans Home Language Anri Matthee Hoërskool Overberg 297.8 Computer Applications Technology Christelle Herbst York High School 293.9 English Home Language Christopher Aubin Bishops Diocesan College 291.8 Engineering Graphics and Design Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 298.9 Nathan Matthew Wynberg Boys' High School 298.5 Information Technology Wylie Mathematics Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 299.7 Physical Sciences Tererai Muchabaiwa Malibu High School 300 Physical Sciences Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 300 Physical Sciences Matthys Louis Carstens Hoërskool Durbanville 300 Likhona Nosiphe Centre of Science & Technology 269.6 Isixhosa Home Language Qazisa Category: Excellence Despite Barriers to Learning In This Category, Learners Will Receive R10 000 And A Certificate. This Is Awarded To A Maximum Of Two Candidates With Special Education Needs Who Obtained The Highest Marks In Their Best Six Subjects That Fulfil The Requirements For The Award Of A National Senior Certificate. -

Heritage Statement

HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN APPLICATION TO DEMOLISH EXISTING BUILDING SUBMITTED TO HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE IN TERMS OF NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO 25 OF 1999 SECTION 34 View of site from Campground Bridge building indicated with red arrow, Google Earth 2015 Prepared for Eris Property Group 10th Floor 80 Strand Street Cape Town 8001 E-mail: [email protected] Tel +27 21 410 1160 Fax +27 21 418 2249 PostNet Suite 122 Private Bag X1005 Claremont 7735 Cape Town South Africa Mobile: 0711090900 Fax: 086 511 0389 E-Mail: [email protected] HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN FINAL 17 JULY 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 3 1.3 THE SITE 3 1.4 REPORT SCOPE OF WORK 3 1.5 ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS 3 1.5.1 ASSUMPTIONS 3 1.5.2 LIMITATIONS 3 1.6 SPECIALIST TEAM AND DETAILS 3 1.7 DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 3 1.8 REPORT STRUCTURE 4 SECTION 2 STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2 ADMINISTRATIVE CONTEXT AND STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2.2 NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO. 25 OF 1999 (NHR ACT) 5 2.2.3 MUNICIPAL POLICY AND PLANNING CONTEXT 6 SECTION 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE AND CONTEXT 9 3.1 NEWLANDS DEVELOPMENT 9 3.2 CONTEXTUAL ASSESSMENT OF SITE 11 3.3 DEVELOPMENT OF SITE 12 3.4 CONTEXT 16 3.5 SITE 18 SECTION 4 SITE & CONTEXT IDENTIFIED HERITAGE RESOURCES & STATEMENT OF HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCES 20 4.1 INTRODUCTION 20 4.2 SITE AND CONTEXT: PROVISIONAL STATEMENT OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 20 SECTION 5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.1 CONCLUSION 22 5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.3 SOURCES 22 BRIDGET O’DONOGHUE ARCHITECT, HERITAGE SPECIALIST ENVIRONMENT 2 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION Tommy Brummer Town Planners on behalf of their client, Eris Property Group appointed Bridget O’Donoghue Architect, Heritage Specialist, Environment for a Heritage Statement for the proposed demolition of the existing building situated on Erf 177552 Newlands Cape Town. -

Itc2014artist Prog Final.Pdf

FESTIVAL CREDITS CONTENTS 2 21 Rotting Treasures Lindokuhle Nkosi and Curator: Jay Pather Africa Centre 3 Curator’s Note Khanyilise Mbongwa Festival Manager: Adrienne van Eeden-Wharton 4 Festival Partners Poetry Pop-Up Shop Badalisha Poetry X-change Financial Manager: Felicia Pattison-Bacon Festival Centre 22 Voyeur Piano Mareli Stolp Curatorial Assistance: Nadja Daehnke Smellscapes Tammy Frazer Technical Managers: Themba Stewart & Ryno Keet 5 PROGRAMME A 23 Store Front and Centre Farzanah Badsha Exhibition Installation: Justin Brett Carpe Minuta Prima (buying) Brian Lobel 6 Back The Forgotten Angle Theatre Collaborative Arts Aweh! Programme Manager: Malika Ndlovu 24 Cubicle Michaelis School of Fine Art Thoriso le Morusu Neo Muyanga Steal My Photograph Lukas Renlund Fundraising: Ivana Abreu 7 Private Moments in Public Spaces * 25 Mosaic Art Spier Arts Academy Office Manager:Ethel Ntlahla Hatch Mamela Nyamza * Invisible Paintings Wojciech Gilewicz Marketing and Publicity: Mango-OMC 8 BDSM Rhine Bernardino * Graphic Design and Layout: Pulling Rabbits The Accumulation is Primitive Pedro Bustamante * 26 PROGRAMME E Website Development: Zero Zero One 9 Couched Shaun Oelf and Grant van Ster * Dark Cell Themba Mbuli * 27 Feed Graeme Lees 10 Wall-Hug Kira Kemper * Uncles & Angels Nelisiwe Xaba and 100 Years of Symphony Cape Town Philharmonic Mocke J van Veuren Orchestra 28 Say Yes or Die Anne Rochat, Gilles Furtwängler and 11 Polite Force Christian Nerf * Sarah Anthony Surveillance Stage Alien Oosting * The Homecoming BALL: bushWAACKing ODIDIVA -

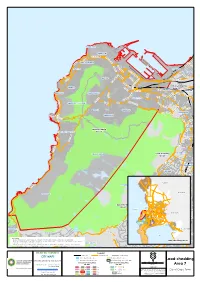

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Inequality in Digital Personas 2018

Inequality in Digital Personas Travis Noakes INEQUALITY IN DIGITAL PERSONAS - e-portfolio curricula, cultural repertoires and social media Travis Noakes Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Humanities, Centre for Film and Media Studies, February, 2018. Supervisor: Professor Marion Walton in the Centre for Film and Media Studies, Faculty of Humanities at the University of Cape Town Co-supervisor: Professor Johannes Cronjé University fromof theCape Town Faculty of Informatics and Design at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology University of Cape Town, South Africa 3 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Inequality in Digital Personas Travis Noakes COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. As a UCT thesis publication, this document is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. University of Cape Town, South Africa 1 Inequality in Digital Personas Travis Noakes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis emerged as an accomplished dish from a primordial soup thanks to: Professor Marion Walton identified the broth’s potential and nurtured its lengthy bubbling with the choicest cooking ingredients and advice. -

SACS High School Prospectus

SACS High School Prospectus SACS High School Prospectus Physical Address: Newlands Avenue Newlands Postal Address: Private Bag, Newlands, Cape Town, 7725 Ph: 021-6894164 Fax: 021-6852669 Admissions Secretary: Mrs Irene Innes – [email protected] Brief History SACS is the oldest high school in South Africa, founded in September 1829. It is arguably the most magnificent setting at the foot of Table Mountain and Devils peak. The concept of the South African College was first formed in 1791 when the Dutch Commissioner-General, Jacob Abraham Uitenhage de Mist, asked for funding to be set aside to improve schooling in the Cape. After the British took over control of the Cape Colony its first governor, Lord Charles Henry Somerset PC, gave permission for the funds reserved by de Mist to be used to establish the South African College in 1814. It was decided in 1874 that the younger students should be separated from their older counterparts. The South African College was separated into the College which became the University of Cape Town and the College School. The College School moved to its own building on Orange Street, separate from the College, in 1896. For the next few decades, the school grew and the building became too small for the number of students attending. In 1959 the school moved to its current home in the Montebello Estate in Newlands,] former home of the mining magnate Sir Max Michaelis, after a decade-long negotiation with the Cape Administration. SACS High School Mission Statement “The South African College High School seeks to promote excellence within an all-round education, to prepare boys to play a constructive role as compassionate, thinking individuals in society”. -

A-League Gala Program

Rondebosch Boys’ High School Lane allocation: Lane Schools 1 Hoërskool DF Malan 2 Elkanah House High School 3 Fairmont High School 4 St Cyprian’s School Wynberg Boys’ High School 5 Herschel Girl’s School Bishops Diocesan College 6 Rustenburg Girls’ High Rondebosch Boys’ High School School 7 Springfield Convent School SACS 8 Stellenberg High School 9 Milnerton High School Rules • Swimmers may only: o swim in one age group, excluding Open events. o Take part in a maximum of two individual races. o Take part in a maximum of two relay races. • Point allocation: o Relays; 1st = 20 points, 2nd = 18 etc. o Individual races; 1st = 10 points, 2nd = 9 points etc. • All events are 50m unless otherwise stated • Change rooms are demarcated. Race order: EVENT GROUP AGE EVENT NUMBER 1 girls OPEN 200m Individual Medley 2 boys OPEN 200m Individual Medley 3 girls U14 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 4 boys U14 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 5 girls U16 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 6 boys U16 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 7 girls U19 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 8 boys U19 4 x 50m Freestyle relay 9 girls U14 Breaststroke 10 boys U14 Breaststroke 11 girls U16 Breaststroke 12 boys U16 Breaststroke 13 girls U19 Breaststroke 14 boys U19 Breaststroke 15 girls U14 Backstroke 16 boys U14 Backstroke 17 girls U16 Backstroke 18 boys U16 Backstroke 19 girls U19 Backstroke 20 boys U19 Backstroke 21 girls U14 Butterfly 22 boys U14 Butterfly 23 girls U16 Butterfly 24 boys U16 Butterfly 25 girls U19 Butterfly 26 boys U19 Butterfly 27 girls U14 Freestyle 28 boys U14 Freestyle 29 girls U16 Freestyle 30 -

High Schools National Distribution List 75 000 Distributed Monthly

SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOLS’ NEWSPAPER HIGH SCHOOLS NATIONAL DISTRIBUTION LIST 75 000 DISTRIBUTED MONTHLY FREE 4 ALL (Pty) Ltd Reg. No: 96/05340/07 P O Box 268, Kloof 3640 Phone: 031 763 3916 47 Sherwood Drive, Fax: 031 763 3721 Kloof 3610 www.free4all.co.za • South Africa’s only national newspaper dedicated to teenagers / High School learners • 75 000 printed monthly and distributed under contract and free-of-charge to High Schools in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Western Cape • Endorsed and supported by senior educationists, school principals, teachers and parents GAUTENG SCHOOLS AREA QUANTITY Alberton High School Alberton 350 Allen Glen High School Roodepoort 450 Athlone Boys’ High School Bez Valley 300 Athlone Girls’ High School Bez Valley 350 Barnato Park High School Berea 350 Birchleigh High School Birchleigh 350 Blue Hills College Midrand 150 Brakpan High School Brakpan 350 Centurion College Joubert Park 200 Dansa International College Pretoria 250 Dawnview High School Germiston 300 Dinwiddie High School Germiston 350 Dominican Convent School Jeppestown 200 Edenglen High School Edenglen 500 Ekangala Comprehensive High School Ekangala 500 Elite College Isando 200 Eureka High School Springs 250 Falcon Educational School Boksburg 200 Ferndale High School Randburg 250 Forest High School Forest Hill 350 Geluksdal Secondary School Geluksdal 300 Glenvista High School Glenvista 100 Greenside High School Greenside 250 Greenwood College Pretoria West 100 Hillview High School Pretoria 350 Hoërskool Florida Florida 400 Hoërskool Randburg Randburg 350 Hoërskool Waterkloof Waterkloof 500 Holy Family College Parktown 150 Immaculata Secondary School Diepkloof 450 Jameson High School Dersley Park 400 Jeppe High School for Boys Kensington 350 Jeppe High School for Girls Kensington 350 John Orr Technical High School Milpark 350 GAUTENG SCHOOLS cont.