Inequality in Digital Personas 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Cape Education Department

WESTERN CAPE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT CRITERIA FOR THE NATIONAL SENIOR CERTIFICATE (NSC) AWARDS FOR 2011 AWARDS TO SCHOOLS CATEGORY 1 - EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE In this category, awards are made to the top twenty schools in the province (including independent schools) that have achieved excellence in academic results in 2011, based on the following criteria: (a) Consistency in number of grade 12 candidates over a period of 3 years (at least 90%) of previous years (b) an overall pass rate of at least 95% in 2011 (c) % of candidates with access to Bachelor’s degree (d) % of candidates with Mathematics passes Each school will receive an award of R15 000 for the purchase of teaching and learning support material. CATEGORY 1: EXCELLENCE IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE No SCHOOL NAME 1. Rustenburg High School for Girls’ 2. Herschel Girls School 3. Diocesan College 4. Herzlia High School 5. Rondebosch Boys’ High School 6. Westerford High School 7. Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 8. South African College High School 9. Centre of Science and Technology 10. Paul Roos Gimnasium 11. York High School 12. Stellenberg High School 13. Wynberg Boys’ High School 14. Paarl Gimnasium 15. The Settlers High School 16. Hoër Meisieskool La Rochelle 17. Hoërskool Durbanville 18. Hoërskool Vredendal 19. Stellenbosch High School 20. Hoërskool Overberg 21. South Peninsula High School 22. Norman Henshilwood High School 2 CATEGORY 2 - MOST IMPROVED SCHOOLS Category 2a: Most improved Public Schools Awards will be made to schools that have shown the greatest improvement in the numbers that pass over the period 2009-2011. Improvement is measured in terms of the numbers passing. -

Newsletter-9-17.Pdf

30 March2017 Dear Parent/Guardian NEWSLETTER 9/17 We have reached the end of a highly successful term. So much has been achieved and we have big dreams and plans for the remainder of the year. Allow me this opportunity to thank every dedicated educator, coach and learner for their hard work and commitment. It is wonderful to see the scale of participation and the level at which we are competing now. Sport and culture have gone from strength to strength. Add to that the excellent academic results we attained last year, and you have to agree that our school is blessed with exceptional learners, educators and parents. During a recent visit by the Curro Transformation and Diversity team, we were complimented on the friendliness of our learners and staff. They noticed how learners went out of their way to greet them and to assist where they could. We also often get compliments from visitors, who work with our learners, regarding their ability to think out of the box and come up with new ideas and solutions. Schools close on Friday, 31 March at 11:00. Reports will be issued to learners on this day. Term 2 starts on Wednesday, 19 April. Educators already start on Tuesday, 18 April. Enjoy a well-deserved break with your children. May God keep you safe and may you experience a blessed Easter. STAFF MATTERS We wish to congratulate Mr Christiaan Botha who attended the North-West University of Potchefstroom’s graduation ceremony to receive his Bachelor’s Degree in Education (BEd). Congratulations to Mrs Mariëtte Viljoen whose daughter, Obie, had a baby girl earlier this week. -

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards for 2017

National Senior Certificate (NSC) Awards For 2017 Awards to learners Learners Will Receive Awards For Excellence In Subject Performance, Excellence Despite Barriers To Learning, Special Ministerial Awards And For The Top 50 Positions In The Province. All Learners Will Receive A Monetary Award And A Certificate. Category : Learner Subject Awards In This Category, One Award Is Handed To The Candidate With The Highest Mark In The Designated Subjects. Each Learner Will Receive R 6 000 And A Certificate. Subject Description Name Centre Name Final Mark Accounting Kiran Rashid Abbas Herschel Girls School 300 Accounting Rita Elise Van Der Walt Hoër Meisieskool Bloemhof 300 Accounting Philip Visage Hugenote Hoërskool 300 Afrikaans Home Language Anri Matthee Hoërskool Overberg 297.8 Computer Applications Technology Christelle Herbst York High School 293.9 English Home Language Christopher Aubin Bishops Diocesan College 291.8 Engineering Graphics and Design Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 298.9 Nathan Matthew Wynberg Boys' High School 298.5 Information Technology Wylie Mathematics Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 299.7 Physical Sciences Tererai Muchabaiwa Malibu High School 300 Physical Sciences Erin Michael Solomon Rondebosch Boys' High School 300 Physical Sciences Matthys Louis Carstens Hoërskool Durbanville 300 Likhona Nosiphe Centre of Science & Technology 269.6 Isixhosa Home Language Qazisa Category: Excellence Despite Barriers to Learning In This Category, Learners Will Receive R10 000 And A Certificate. This Is Awarded To A Maximum Of Two Candidates With Special Education Needs Who Obtained The Highest Marks In Their Best Six Subjects That Fulfil The Requirements For The Award Of A National Senior Certificate. -

Elusive Equity : Education Reform in Post-Apartheid South Africa / Edward B

������������������������������������������������ ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p � � � �� �� �� ��� � Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc Elusive Equity Title.pdf 4/6/2005 4:10:21 PM ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p C M Y Education reform in CM post-apartheid South Africa MY CY CMY K Free download from www.hsrc Edward B Fiske & Helen F Ladd ABOUT BROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, educa- tion, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal pur- pose is to bring knowledge to bear on current and emerging policy problems. The Institu- tion maintains a position of neutrality on issues of public policy. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors. Copyright © 2004 Edward B. Fiske and Helen F. Ladd ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 (fax: 202/797-6195 or e- mail: [email protected]). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Fiske, Edward B. Elusive equity : education reform in post-apartheid South Africa / Edward B. Fiske and Helen F. Ladd. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8157-2840-9 (cloth : alk. paper) Free download from www.hsrc 1. Educational equalization—South Africa. 2. Education and state—South Africa. 3. -

WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 6 22 February 2018

Westerford Newsletter 6 (22 February 2018) WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 6 22 February 2018 FROM THE OFFICE…. Thank you for the parent assistance at SLOG. The supply of snacks was never-ending. So appreciated. Somebody sent in a basket full of marmite scones. Everybody wants the recipe! If the parent who sent them in would like to share, we would love the recipe. Please send it to: [email protected] There are plenty of knitted squares that need crocheting or sewing into blankets before winter. Please come and collect some if you are able. Thank you. TENNIS COACHING JOB We are looking for someone who can coach the 4th and 5th team Tennis girls on Tuesdays after 15:15 from next week. OW and parents welcome to apply. Starting date: 27 February Please contact Ms McLaren [email protected] or Ms A Gray [email protected] SCIENCE AND FAITH On Thursday 8 February at second break, CU (Christian Union) had the privilege of hosting Dr Derek Fish, a talented physicist, passionate about science as well as his faith. Dr Fish addressed a large group of Westerfordians about how, contrary to popular belief, science and religion do not have to clash, but instead overlap and can go hand in hand. He shared many quotes with us from famous scientists in the past about faith and science coinciding, as well as comparing scientific fact to what the Bible states. Dr Fish also made time towards the end to answer some of the pressing questions the Westerfordians at the event had, many of which would have been difficult for the average person to answer! A huge thank you to Dr Fish for taking time to share his incredible insight and wisdom on this subject with Westerford. -

Herzlia AGM Addresses Challenges And

We are proud of the service we have provided to Trustees and Owners of Bodies Corporate and Homeowners Associations over 15 years. If we don’t already manage your apartment block or complex, we would like to. CONTACT Mike Morey TEL (021) 426 4440 FAX (021) 426 0777 EMAIL [email protected] VOLUME 29 No 6 JULY 2012 5772 www.cjc.org.za Herzlia AGM addresses Inspiring16082_Earspace UJC for Jewish General Chronicle FA.indd 1 Meeting2011/08/19 10:40 AM challenges and achievements The Biennial General Meeting of the United Jewish Campaign (UJC) took place on Monday 4 June at the Albow Centre campus. he UJC is the central fundraising Tagency of the Cape Town Jewish community. The organisation was constituted to allow the beneficiaries of the campaign to fulfil their respective missions, with primary fundraising pressures being assumed by the UJC. Gerald Kleinman, Philip Krawitz and Eliot Osrin. Some 100 individuals from across the community gathered to hear the results Dr David Klatzow was the keynote of the 2011 United Jewish Campaign and speaker, delivering an excellent address. learn more about the objectives for 2012. Continued on page 9 The new committee: Front: Bernard Osrin, Geoff Cohen, Dr Mark Todes, Gary Nathan, Tanya Golan (Chairperson) and David Ginsberg. Middle: Marianne Marks, Lizbe Botes, Franki Cohen, Michelle Scher, Dr Glenda Kruss van der Heever, Janine Fleischmann and Jos Horwitz. Cape Board hosts Back: Ivan Klitzner, Evan Feldman, Ari Zelezniak, Hilton Datnow, Warren Kaimowitz, Daniel Kurgan, Anton Krupenia and Ronnie Gotkin. ground-breaking debate At United Herzlia Schools’ 72nd AGM, curriculum. -

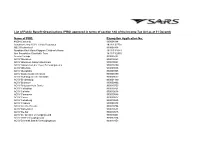

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV -

Behind Every Good List, There Lies a Determined

CAREERS Careers, 18-Oct-2009-Page 11, Cyan Careers, 18-Oct-2009- Page 11, Magenta Careers, 18-Oct-2009-Page 11, Yellow Careers, 18-Oct-2009- Page 11, Black C-1 JDCP Sing the praises of these state schools Champions stand proud in SA’s public education landscape THE Sunday Times commissioned the “The intention of this was to reward University of the Witwatersrand’s visiting schools for the total number of pupils researcher Helen Perry to identify the Top encouraged to do these subjects, as well as 100 government schools in the country. how well these pupils did in the exams. The matrics of 2008, on which the survey “In so doing, we avoid unduly rewarding is based, are the first graduates of the new schools that selected only their best stu- curriculum introduced in stages 12 years dents to sit for these subjects.” ago. Schools with 50 or more pupils were The Sunday Times has revived the To p considered for the survey. 100 schools project, last undertaken by the The index considers academic achieve- newspaper 10 years ago, to give its readers ment and is calculated by combining these the information necessary to make “the five factors: single most important decision parents ■ Matric pass rate; will make — where to educate their chil- ■ Percentage of pupils with a university dren”, said Sunday Times editor Mondli entrance pass; M a k h a nya . ■ The average number of A symbols; “We also want to celebrate schools that ■ The number of maths candidates achieving have achieved excellence, demonstrate over 50%, as a percentage of all candidates why they performed so well, and highlight at the school; the top schools as role models for others to ■ The number of science candidates achiev- learn from,” he said. -

WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 18 31 May 2018

Westerford Newsletter 18 (31 May 2018) WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 18 31 May 2018 EXCURSIONS, TOURS, EXCHANGES AND EXPEDITIONS OFFERED TO OUR PUPILS AT WESTERFORD Unfortunately, in last week’s edition, the more established of our two trips to the Transkei region of the Eastern Cape was omitted. We apologise to the excursion organiser, Mr Dugmore, and all those interested in what is a wonderful, and in many ways potentially life-transforming opportunity. The information follows: TRANSKEI HIKE Purpose of the hike: The purpose of the hike is to provide pupils studying isiXhosa with an opportunity to deepen their understanding of the Language and Culture as they walk through the rural Eastern Cape for six days. Pupils are also introduced to the work being done in Health and Education in the Zithulele area where Westerford has an active link with a number of Old Westerfordians. To which grade and / or subject is the tour offered? In the early days the trip included a combination of Grade 10 and Grade 11 Xhosa SAL (Second Additional Language) pupils. Due to its popularity, the trip is currently offered only to Grade 11 Xhosa SAL pupils. How frequently is the hike offered? This hike is usually offered annually during the September / October holidays. (2018 will be the 18th tour) Is the organisation of the tour undertaken by a Westerford TIC (Teacher-in-Charge), or an 'outside entity'? The organisation and planning is done by Westerford teacher, Mr Dugmore, Head of isiXhosa. 1 Westerford Newsletter 18 (31 May 2018) WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL GLORIOUS RAIN Oliver Twist sings “Food, Glorious, Food!” in the musical of that name. -

District Directory 2003-2004

Handbook and Directory for Rotarians in District 9350 2017 – 2018 0 Rotary International President 2017-2018 Ian Riseley Ian H. S. Riseley is a chartered accountant and principal of Ian Riseley and Co., a firm he established in 1976. Prior to starting his own firm, he worked in the audit and management consulting divisions of large accounting firms and corporations. A Rotarian in the Rotary Club of Sandringham, Victoria, Australia since 1978, Ian has served Rotary as treasurer, director, trustee, RI Board Executive Committee member, task force member, committee member and chair, and district governor. Ian Riseley has been a member of the boards of both a private and a public school, a member of the Community Advisory Group for the City of Sandringham, and president of Beaumaris Sea Scouts Group. His honors include the AusAID Peacebuilder Award from the Australian government in 2002 in recognition of his work in East Timor, the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to the Australian community in 2006, and the Regional Service Award for a Polio-Free World from The Rotary Foundation. Ian and his wife, Juliet, a past district governor, are Multiple Paul Harris Fellows, Major Donors, and Bequest Society members. They have two children and four grandchildren. Ian believes that meaningful partnerships with corporations and other organizations are crucial to Rotary’s future. “We have the programs and personnel and others have available resources. Doing good in the world is everyone’s goal. We must learn from the experience of the polio eradication program to maximize our public awareness exposure for future partnerships. -

Westerford High School Diversity and Inclusivity Policy

DIVERSITY & INCLUSIVITY POLICY WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL FEBRUARY 2021 POLICY A12 WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL DIVERSITY AND INCLUSIVITY POLICY 1. Introduction to the policy 1.1 The School recognises, values and promotes diversity, inclusion and belonging in all ways and aims to encourage positive personal relationships in an environment where individuals feel free to be themselves and are treated with dignity and respect. 1.2 This policy seeks to ensure that all, regardless of their race, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, religion or any other prohibited grounds1, feel safe and comfortable at Westerford. In doing so the policy aims to instil an inclusive climate in the School. 1.3 This policy aims to eliminate all forms of unfair discrimination and to encourage open discussions amongst all members of the community. The community includes all current pupils and members of staff of Westerford, including grounds staff, cleaning staff, casual staff, administrative staff and teaching staff. This would be done by holding discussions for parents through the Parent Network Group (PNG), engaging in ongoing education with staff and pupils, among other things. The aim is to help to create an environment in which all members of the community thrive. 1.4 The Life Orientation syllabus at the School must include, at an appropriate stage in the experience of the pupils at the School, education in both the form and content of this policy, and the objectives which underlie its adoption. 2. Objectives of the Policy: This policy seeks: 2.1 to foster an environment where everyone associated with the School is treated with courtesy, dignity and respect; 2.2 to provide a mechanism for the reporting of any kind of unfairly discriminatory behaviour, conscious or unconscious, and then to ensure that an effective process is followed to resolve these complaints in a fair, timeous and appropriately confidential manner. -

WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 5 15 February 2018

Westerford Newsletter 5 (15 February 2018) WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter 5 15 February 2018 MUSIC DEPARTMENT: Junior Schools tours kick off at Kirstenhoff OUTDOOR CLUB HIKE On Friday, Outdoor Club hosted their first hike of the year; numerous juniors attended, getting involved in an activity at Westerford for the first time. The group started at the top gate of Kirstenbosch and enjoyed a scenic walk through the grounds to the start of the Nursery Ravine trail. After hiking along the major path for a while they turned off to a lesser-used path and ended at the breathtaking Rooikat Waterfall. Well done to Outdoor for organising such a stunning and successful event; many are looking forward to the next one with baited breath! Hannah McDougall, Grade 12 1 Westerford Newsletter 5 (15 February 2018) WESTERFORD HIGH SCHOOL THE DECEMBER TRIP TO CHINA On 5 December 2017, a party of four – Mr Jamy Li, our Mandarin teacher, Mr Patrick Jordi, Mrs Anne McLaren and her husband Mr Bernard Geldenhuys – left on a ten day visit to China that took in the cities of Beijing, Xi’an and Tianjin. The primary purpose of this adventure was to attend the 12th Annual Confucius Institute Conference, an international gathering of Mandarin educators hosted in the ancient capital of Xi’an. The trip to China allowed too for some sightseeing, the opportunity to connect with Mr Qi (a former Westerford Mandarin teacher) and for Mr Li to catch up with friends and family. Arriving in Beijing, we felt at once the impact of this vast city: its heavy traffic, numerous apartment blocks and thousands of bicycles.