William Henry Squire's Out-Of-Print Works for Cello and Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of Robert Squire Generation No. 1 1. ROBERT1 SQUIRE was born Abt. 1650 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died 26 Nov 1702 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married MARY. She died 24 Oct 1701 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Child of ROBERT SQUIRE and MARY is: 2. i. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE, b. 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. Generation No. 2 2. FRANCIS2 SQUIRE (ROBERT1) was born 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (1) MARGARET TROWING 17 May 1694 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born Abt. 1670 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England, and died Jun 1700 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. He married (2) ESTER GEATON 06 Jan 1703 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. She was born 1676 in St Giles in the Wood, and died 1750 in St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE: Baptism: 18 Oct 1670, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Notes for MARGARET TROWING: Name could be Margaret Crowling. More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING: Marriage: 17 May 1694, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About ESTER GEATON: Baptism: 21 May 1676, St Giles in the Wood Burial: 24 Apr 1750, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England More About FRANCIS SQUIRE and ESTER GEATON: Marriage: 06 Jan 1703, St Giles in the Wood, Devon, England Children of FRANCIS SQUIRE and MARGARET TROWING are: i. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-Soprano with J. Hunter Macmillan, Piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul's Galley (“Songs Of

1 CARMEN DAAH Mezzo-soprano with J. Hunter MacMillan, piano Recorded London, January 1925 MC-6847 Kishmul’s galley (“songs of the Hebrides”) (trad. arr. Marjorie Kennedy Fraser) Bel 705 MC-6848 The spinning wheel (Dunkler) Bel 705 MC-6849 Coming through the rye (Robert Burns; Robert Brenner) Bel 706 MC-6850 O rowan tree – ancient Scots song (trad. arr. J. H. MacMillan) Bel 707 MC-6851 Jock o’ Hazeldean (Walter Scott; trad. arr. J. Hunter MacMillan Bel 706 MC-6853 The herding song (trad. arr. Mrs. Kennedy Fraser) Bel 707 THE DAGENHAM GIRL PIPERS (formed 1930) Led by Pipe-Major Douglas Taylor. 12 pipers, 4 drummers Recorded Chelsea Town Hall, King’s Road, London, Saturday, 19th. November 1932 GB-5208-1/2 Lord Lovat’s lament; Bruce’s address – lament (both trad) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5209-1/2 Earl of Mansfield – march (John McEwan); Lord Lovat’s – strathspey (trad); Mrs McLeod Of Raasay – reel (Alexander MacDonald) Panachord 25365; Rex 9584 GB-5210-1 Highland Laddie – march (trad); Lady Madelina Sinclair – strathspey (Niel Gow); Tail toddle reel (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 GB-5211-3 An old Highland air (trad) Panachord 25370; Rex 9585 Pipe Major Peggy Isis (solos); 15 pipers; 4 side drums; 1 bass drum. Recorded Studio No. 2, 3 Abbey Road, London, Tuesday, 26th. March 1957 Military marches – intro. Scotland the brave; Mairi’s wedding; Athole Highlanders (all trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Pipes in harmony – intro. Maiden of Morven (trad); Green hills of Tyrol (Gioacchino Rossini. arr. P/M John MacLeod) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Corn rigs – march (trad); Monymusk – strathspey (Daniel Dow); Reel o’ Tulloch (John MacGregor); Highland laddie (trad) Par GEP-8634(EP); CapUS T-10125(LP) Quick marches – intro. -

Eda Kersey Führung Von Samuel Barbers Violinkonzert Op

Kersey, Eda Eda Kersey führung von Samuel Barbers Violinkonzert op. 14. Dar- über hinaus nahm sie einen Teil dieser Konzerte für die * 15. Mai 1904 in Goodmayes, England BBC auf und gab u. a. die erste Rundfunkaufführung von † 13. Juli 1944 in Ilkley (Yorkshire), England Ernst von Dohnányis Violinkonzert d-Moll op. 27. Orte und Länder Violinistin Eda Kersey wurde in Goodmayes, in der Grafschaft Ess- „The double concerto [...] does not show Brahms in his ex geboren und wuchs u. a. in Southsea (Portsmouth, easiest mood, but it was beautifully played last night by Hampshire) auf. Ab 1917 lebte sie in London, wo sie pri- Miss Eda Kersey and Miss Thelma Reiss. [...] The coope- vat Violine studierte, und behielt dort zeitlebens ihren ration of the two players was all that could be desired, Wirkungskreis bei. Zudem konzertierte sie regelmäßig in and Sir Henry Wood gave them every help to realize to zahlreichen weiteren Städten Englands, u. a. in South- the full their conception of a work which rarely sounds hampton, Birmingham, Harrogate, Leeds und Norwich. so persuasive and convincing, even to its admirers, as it Sie starb in Ilkley in der Grafschaft Yorkshire. did in their hands.“ Biografie „Das Doppelkonzert […] zeigt Brahms nicht gerade in sei- Eda Kersey wurde am 15. April 1904 in Goodmayes, in ner unbeschwertesten Stimmung, doch es wurde letzten der Grafschaft Essex geboren. Ihre musikalische Ausbil- Abend von Fräulein Eda Kersey und Fräulein Thelma dung erhielt sie überwiegend in privatem Unterricht, zu- Reiss wundervoll gespielt. […] Die Zusammenarbeit der nächst am Klavier, ab dem Alter von sechs Jahren auch beiden Spielerinnen hatte alles, was man sich wünschen in Violine. -

029I-HMVNX1919X03-0000A0.Pdf

`the World's GREATEST ARTISTS record for McCORMACKFARRARJOURNET KIRKBY LUNN FRANZ BATTISTINI ELMAN STRING QUARTET NEW QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA (Proprietors-Messrs. Chappell & Co., Ltd.) conducted by Mr. ALICK MACLEAN 12inch double-sided record 7s. Ballet Music from "Faust," Part I Nos. 1 & 2 Gounod Ballet Music from "Faust," Part II Nos. 3 & 4 Goarnad A NEW triumph in orchestral recording has been achieved by the famous Queen's Hall instrumentalists in their reproduction of the ballet music from Gounod's " Faust." The exquisite music, famous so full of that sense of youth and romance which has given the is by finish opera its world-wide popularity, played them with a perfect delicate and beauty of tone in the orchestration, as well as great charm of expression. The first number is one of those graceful and flower-like waltz tunes that Gounod knew so well how to write ; then, in contrast, the following number is more serious and sentimental in character. The third dance is a gem of sparkling melody and fascinating rhythm, the orchestra being particularly fine in this movement. Finally comes the march-like tune which ends the suite so brilliantly, else closing bars 79) of the music being most charming in effect. (Speed THE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA conducted by SIR FREDERIC H. COWEN 12-inch record 6s. 2-0847 Country dance-" Old English Dances " 1st set Published by Novelle & Co. AMONG our composers of to-day none has more worthily than Sir Frederic Cowen upheld the great tradition of English music- melodiousness-that gift of a lilting tune which, centuries ago, helped to give this country its immortal title of " Merrie England." This brilliant dance, a striking example of the composer's genius, is redolent of the olden-time English countryside, its principal melody so jolly and fresh and so picturesque in its instrumentation. -

Roger Quilter

ROGER QUILTER 1877-1953 HIS LIFE, TIMES AND MUSIC by VALERIE GAIL LANGFIELD A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham February 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Roger Quilter is best known for his elegant and refined songs, which are rooted in late Victorian parlour-song, and are staples of the English artsong repertoire. This thesis has two aims: to explore his output beyond the canon of about twenty-five songs which overshadows the rest of his work; and to counter an often disparaging view of his music, arising from his refusal to work in large-scale forms, the polished assurance of his work, and his education other than in an English musical establishment. These aims are achieved by presenting biographical material, which places him in his social and musical context as a wealthy, upper-class, Edwardian gentleman composer, followed by an examination of his music. Various aspects of his solo and partsong œuvre are considered; his incidental music for the play Where the Rainbow Ends and its contribution to the play’s West End success are examined fully; a chapter on his light opera sheds light on his collaborative working practices, and traces the development of the several versions of the work; and his piano, instrumental and orchestral works are discussed within their function as light music. -

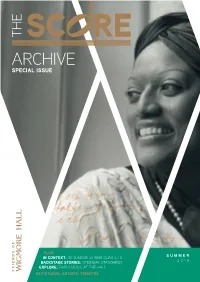

Archive Special Issue

ARCHIVE SPECIAL ISSUE PLUS SUMMER IN CONTEXT: SCHUMANN STRING QUARTETS 2018 BACKSTAGE STORIES: STEINWAY STANDARDS EXPLORE: EARLY MUSIC AT THE HALL FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS IN PICTURES: ARTISTS’ TRIBUTES Home to tens of thousands EMILY WOOLF, OUR GUEST of programmes, thousands of photographs, press cuttings, EDITOR, WRITES This edition of The Score is a welcome chance for us to correspondence and more, the invite our Friends into the Wigmore Hall archive, and to Wigmore Hall archive offers us a share with you some of the treasures we have found window into the prestigious (and while exploring its shelves! sometimes surprising!) history of this unique and beloved venue. As well as an overview of early music at Wigmore Hall since the arrival of the first viola da gamba here in 1902, we dig into the performance The process of building a catalogue of our history of Schumann’s lyrical string quartets on our stage and the holdings has also been an extraordinary journey of company they kept; Nigel Simeone writes on the importance of the discovery for us – one which has helped shine a postwar Concerts de Musique Française and the shape of French music at light on the story of concert life in London over the the Hall; we take a look back over a few of our more outstanding song 117 years since the Hall opened in 1901. recitals; open up our enchanting collection of the papers of the violinist As part of our work to bring the history of Gertrud Hopkins and her brother, the pianist Harold Bauer, and explore our Wigmore Hall out of the archive’s boxes, this long association with Steinway Pianos. -

Justin Solomon 1 Deconstructing the Definitive Recording: Elgar's Cello Concerto and the Influence of Jacqueline Du Pré Accou

Justin Solomon 1 Deconstructing the Definitive Recording: Elgar’s Cello Concerto and the Influence of Jacqueline du Pré Accounts of Jacqueline du Pré’s 1965 recording session for the Elgar Cello Concerto with Sir John Barbirolli border on mythical. Only twenty years old at the time, du Pré impressed the audio engineers and symphony members so much that word of a historic performance quickly spread to an audience of local music enthusiasts, who arrived after a break to witness the remainder of the session.1 Reviewers of the recording uniformly praised the passion and depth of du Pré’s interpretation; one reviewer went so far as to dub the disc “the standard version of the concerto, with or without critical acclaim.”2 Even du Pré seemed to sense that the recording session would become legendary. Despite the fact that the final recording was produced from thirty-seven takes spanning the entirety of the Concerto, du Pré hinted to her friends that “she had played the concerto straight through,” as if the recording were the result of a single inspired performance rather than a less glamorous day of false starts and retakes.3 Without doubt, du Pré’s recording is one of the most respected interpretations of the Concerto. Presumably because of the effectiveness of the recording and the attention it received, the famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich “erased the concerto from his repertory” after the recording was released.4 For this reason, it comes as no surprise that in the wake of such a respected and widely distributed rendition, amateur and professional cellists alike would be conscious of du Pré’s stylistic choices and perhaps imitate their most attractive features. -

J. MEREDITH-KAY “Meredith-Kay and His Orchestra” Recorded Blyth Road, Hayes, Middlesex, Monday, 19Th

1 J. MEREDITH-KAY “Meredith-Kay and his Orchestra” Recorded Blyth Road, Hayes, Middlesex, Monday, 19th. October 1925 Cc-6698-1 Schiehallion reel (trad. arr. W. Armstrong) – part 1 HMV C-1225; HMVSA C-1225(12”) Cc-6699-1 Schiehallion reel (trad. arr. W. Armstrong) – part 2 HMV C-1225; HMVSA C-1225(12”) Cc-7000-1 Foursome reel – Highland whisky – strathspey (Niel Gow); Jenny Dang the weaver – reel (Alexander Garden); Lady Mary Ramsay – strathspey (Nathaniel Gow); Reel of Tulloch – reel (John MacGregor) HMV C-1231; HMVSA C-1231(12”) Cc-7001-2 Foursome reel – Lady Madeline Sinclair – strathspey (Niel Gow); Reel of Tulloch – reel (John MacGregor) HMV C-1231; HMVSA C-1231(12”) KATHIE KAY (r.n. Connie Woods) (Gainsborough, 1919 – Largs, 2005). Vocal with orchestra conducted by Frank Cordell Recorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Wednesday, 19th. October 1955 OEA-18439 Suddenly there’s a valley (Chuck Meyer; Biff Jones) HMV POP-126; MFP MFP-1152(LP) Recorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Thursday, 15th. December 1955 OEA -18535 Old Scotch mother (Ray McKay; Joseph Maxwell) HMV POP-167; MFP MFP-1152(LP) Reciorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Thursday, 5th. January 1956 OEA-18529 The wee hoose ‘mang the heather (Gilbert Wells; Fred Elton; Harry Lauder) HMV POP-229; MFP MFP-1152(LP) Recorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Monday, 9th. January 1956 OEA-18525 There is somebody waiting for me (Harry Lauder) HMV POP-167; MFP MFP-1152(LP) Recorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Friday, 18th. May 1956 OEA-18659 Bonnie Scotland (Bell) HMV POP-220; MFP MFP-1152(LP) Recorded 3 Abbey Road, London, Wednesday, 3rd. -

Orme-Stone DMA Document

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Cello Teaching Methods: An Analysis and Application of Pedagogical Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vd8h85z Author Orme-Stone, Chenoa Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Cello Teaching Methods: An Analysis and Application of Pedagogical Literature A supporting document submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Chenoa Kellyanne Orme-Stone Committee in charge: Professor Jennifer Kloetzel, Committee Chair Professor Robert Koenig Professor Nicole Lamartine, Lecturer December 2020 The supporting document of Chenoa Kellyanne Orme-Stone is approved. __________________________________________________ Robert Koenig __________________________________________________ Nicole Lamartine __________________________________________________ Jennifer Kloetzel, Committee Chair December 2020 VITA OF CHENOA KELLYANNE ORME-STONE December 2020 EDUCATION Doctor of Musical Arts, University of California, Santa Barbara, expected December 2020 Master of Music, Royal Danish Academy of Music, June 2017 Bachelor of Music in Cello Performance, Indiana University, Jacobs School of Music, May 2014 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Lotus Chamber Music Festival, Co-Founder and Artistic Director, 2019-present Westmont Academy for Young Artists, Cello Teacher, Summer 2019 Santa Barbara Symphony, -

The Officialorganofthe B.B.C

a BOURNEMOUTH LONDON i: iY ee Err ie 1 iL ae aw ™ ee ar , NT ta [re TAG Ta Hii Tete Le THEaaA a OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE B.B.C Seee Vol. de No. 28. 1G.FA0"asNaineper.t EVERY FRIDAY. Two Pence. * eSee ee a EB = = - OFFICIAL _ What Is Time? PROGRAMMES By J. C. W. Reith, Managinz Director of the B.B.C, yt maj have noticed « paragraph in. these about the time, The sundial was the favourite pages recently to the effect that watch- method of keeping to time, and one supposes takers are benefiting considerably from the they were late if the day were dull. THE BRITISH witeloss signals which are’ broadcast, aa people ‘* .& ih are discovering faults in their clocks and watches Their interests were lose wide than nowadays BROADCASTING and wish them to po better, If a censua wore too, and one must remember that. the 25-mile taken of all the clocks and watches in the howses radius which to ns means the range of « of London, I wonder how many would be found cryatal get meant to them the limit of their COMPANY. to be correct to within sixty seconds, and how visting list and business interests. Oniside that many would be going at all. radius they rarely ventured, and. cared little r- - s = * witet happened beyond it, Small wonderthat the For the Week Commencing Some clocks ate mathematical problems. I sundial wae sufficient for their needs. once heart a clock etrike five when the hands the rushing world of to-day deniands greater SUNDAY, APRIL 6th.