Islam, Politics and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gus Dur, As the President Is Usually Called

Indonesia Briefing Jakarta/Brussels, 21 February 2001 INDONESIA'S PRESIDENTIAL CRISIS The Abdurrahman Wahid presidency was dealt a devastating blow by the Indonesian parliament (DPR) on 1 February 2001 when it voted 393 to 4 to begin proceedings that could end with the impeachment of the president.1 This followed the walk-out of 48 members of Abdurrahman's own National Awakening Party (PKB). Under Indonesia's presidential system, a parliamentary 'no-confidence' motion cannot bring down the government but the recent vote has begun a drawn-out process that could lead to the convening of a Special Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) - the body that has the constitutional authority both to elect the president and withdraw the presidential mandate. The most fundamental source of the president's political vulnerability arises from the fact that his party, PKB, won only 13 per cent of the votes in the 1999 national election and holds only 51 seats in the 500-member DPR and 58 in the 695-member MPR. The PKB is based on the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a traditionalist Muslim organisation that had previously been led by Gus Dur, as the president is usually called. Although the NU's membership is estimated at more than 30 million, the PKB's support is drawn mainly from the rural parts of Java, especially East Java, where it was the leading party in the general election. Gus Dur's election as president occurred in somewhat fortuitous circumstances. The front-runner in the presidential race was Megawati Soekarnoputri, whose secular- nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) won 34 per cent of the votes in the general election. -

Power-Sharing and Political Party Engineering in Conflict-Prone Societies

This article was downloaded by: [Australian National University] On: 26 February 2013, At: 16:43 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Conflict, Security & Development Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccsd20 Power-sharing and political party engineering in conflict-prone societies: the Indonesian experiment in Aceh Ben Hillman Version of record first published: 14 Jun 2012. To cite this article: Ben Hillman (2012): Power-sharing and political party engineering in conflict- prone societies: the Indonesian experiment in Aceh, Conflict, Security & Development, 12:2, 149-169 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2012.688291 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Conflict, Security & Development 12:2 May 2012 Analysis Power-sharing and political party engineering in conflict- prone societies: the Indonesian experiment in Aceh Ben Hillman Establishing legitimate political leadership democracies, but their importance is through non-violent means is an essential magnified in conflict-prone societies. -

Staggering Political Career of Jokowi's Running Mate Cleric Ma'ruf Amin

Staggering Political Career of Jokowi’s Running Mate Cleric Ma’ruf Amin [Antonius Herujiyanto AH0908_090818] Wondering about Jokowi’s decision to choose cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate in the coming Presidential race, many people start to be curious, questioning who the cleric is. Not only is the 75-year-old cleric [he was born on 11 March 1943 in Tangerang, Banten province, Java] the general chairman of the Indonesian Ulema Council [MUI], but he is also the spiritual adviser or Rais Amm to NU [the largest Islamic community organization in the country]. Jokowi seems to expect the cleric to protect him against the criticism that he lacks sufficient Islamic credentials. Having chosen cleric Ma’ruf as his running mate, Jokowi must have thought that he would attract and provide Indonesian voters with his nationalism and cleric Ma’ruf Amin’s Islamism. [It is beside the many “radical” actions conducted by the cleric such as, among others, playing his influential adversary, backing the 2016 massive street protests by conservative Muslims and fuelling a campaign that led to Jokowi’s ally and successor as Jakarta’s governor, Ahok, to be jailed for blaspheming Islam; having pushed behind the scenes for restrictions on homosexuals and minority religious sects while seeking a greater role for Islam in politics.] The cleric was graduated from Tebuireng pesantren [Islamic boarding school] in Jombang, East Java. He earned his bachelor's degree in Islamic philosophy from Ibnu Khaldun University, Bogor, West Java. He was elected as a member of the House of Representatives [DPR], representing the (conservative Islamic) United Development Party or PPP and served as leader of the PPP caucus from 1977 to 1982. -

Islamic Student Organizations and Democratic Development In

ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Troy A. Johnson June 2006 This thesis entitled ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES by TROY A. JOHNSON has been approved for the Center of International Studies Elizabeth F. Collins Associate Professor of Classics and World Religions Drew McDaniel Interim Dean, Center for International Studies Abstract JOHNSON, TROY A., M.A., June 2006, International Development Studies ISLAMIC STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND DEMOCRATIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THREE CASE STUDIES (83 pp.) Director of Thesis: Elizabeth F. Collins This thesis describes how and to what extent three Islamic student organizations – Muhammadiyah youth groups, Kesatuan Aksi Mahasiswa Muslim Indonesia (KAMMI), and remaja masjid – are developing habits of democracy amongst Indonesia's Muslim youth. It traces Indonesia's history of student activism and the democratic movement of 1998 against the background of youth violence and Islamic radicalism. The paper describes how these organizations have developed democratic habits and values in Muslim youth and the programs that they carry out towards democratic socialization in a nation that still has little understanding of how democratic government works. The thesis uses a theoretical framework for evaluating democratic education developed by Freireian scholar Ira Shor. Finally, it argues that Islamic student organizations are making strides in their efforts to promote inclusive habits of democracy amongst Indonesia's youth. Approved: Elizabeth F. Collins Associate Professor or Classics and World Religions Acknowledgments I would like to thank my friends in Indonesia for all of their openness, guidance, and support. -

Zealous Democrats: Islamism and Democracy in Egypt, Indonesia and Turkey

Lowy Institute Paper 25 zealous democrats ISLAMISM AND DEMOCRACY IN EGYPT, INDONESIA AND TURKEY Anthony Bubalo • Greg Fealy Whit Mason First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2008 Anthony Bubalo is program director for West Asia at the Lowy Institute for International Policy. Prior to joining the Institute he worked as an Australian diplomat for 13 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 1360 Australia years and was a senior Middle East analyst at the Offi ce of www.longmedia.com.au National Assessments. Together with Greg Fealy he is the [email protected] co-author of Lowy Institute Paper 05 Joining the caravan? Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 The Middle East, Islamism and Indonesia. Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2008 ABN 40 102 792 174 Dr Greg Fealy is senior lecturer and fellow in Indonesian politics at the College of Asia and the Pacifi c, The All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Australian National University, Canberra. He has been a of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the of Advanced International Studies, Washington DC, and copyright owner. was also an Indonesia analyst at the Offi ce of National Assessments. He has published extensively on Indonesian Islamic issues, including co-editing Expressing Islam: Cover design by Longueville Media Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Religious life and politics in Indonesia (ISEAS, 2008) and Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia (ISEAS, 2005). -

From the Editor

EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor ELIZABETH SKINNER Editor Happy New Year, everyone. As I write this, we’re a few weeks into 2021 and there ELIZABETH ROBINSON Copy Editor are sparkles of hope here and there that this year may be an improvement over SALLY BAHO Copy Editor the seemingly endless disasters of the last one. Vaccines are finally being deployed against the coronavirus, although how fast and for whom remain big sticky questions. The United States seems to have survived a political crisis that brought EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD its system of democratic government to the edge of chaos. The endless conflicts VICTOR ASAL in Syria, Libya, Yemen, Iraq, and Afghanistan aren’t over by any means, but they have evolved—devolved?—once again into chronic civil agony instead of multi- University of Albany, SUNY national warfare. CHRISTOPHER C. HARMON 2021 is also the tenth anniversary of the Arab Spring, a moment when the world Marine Corps University held its breath while citizens of countries across North Africa and the Arab Middle East rose up against corrupt authoritarian governments in a bid to end TROELS HENNINGSEN chronic poverty, oppression, and inequality. However, despite the initial burst of Royal Danish Defence College change and hope that swept so many countries, we still see entrenched strong-arm rule, calcified political structures, and stagnant stratified economies. PETER MCCABE And where have all the terrorists gone? Not far, that’s for sure, even if the pan- Joint Special Operations University demic has kept many of them off the streets lately. Closed borders and city-wide curfews may have helped limit the operational scope of ISIS, Lashkar-e-Taiba, IAN RICE al-Qaeda, and the like for the time being, but we know the teeming refugee camps US Army (Ret.) of Syria are busy producing the next generation of violent ideological extremists. -

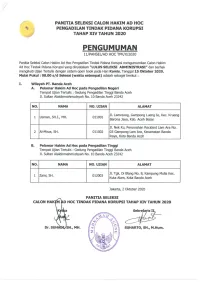

PENGUMUMAN Ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020

PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : I. Wilayah PT. Banda Aceh A. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Negeri Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Lamreung, Gampong Lueng Ie, Kec. Krueng 1 Usman, SH.I., MH. 011001 Barona Jaya, Kab. Aceh Besar Jl. Nek Ku, Perumahan Recident Lam Ara No. 2 Al-Mirza, SH. 011002 03 Gampong Lam Ara, Kecamatan Banda Raya, Kota Banda Aceh B. Pelamar Hakim Ad Hoc pada Pengadilan Tinggi Tempat Ujian Tertulis : Gedung Pengadilan Tinggi Banda Aceh Jl. Sultan Alaidinmahmudsyah No. 10 Banda Aceh 23242 NO. NAMA NO. UJIAN ALAMAT Jl. Tgk. Di Blang No. 8, Kampung Mulia Kec. 1 Zaini, SH. 012003 Kuta Alam, Kota Banda Aceh Jakarta, 2 Oktober 2020 PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 Dr. SUHA SUHARTO, SH., M.Hum. PANITIA SELEKSI CALON HAKIM AD HOC PENGADILAN TINDAK PIDANA KORUPSI TAHAP XIV TAHUN 2020 PENGUMUMAN ll/PANSEL/AD HOC TPK/X/2020 Panitia Seleksi Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi mengumumkan Calon Hakim Ad Hoc Tindak Pidana Korupsi yang dinyatakan "LULUS SELEKSI ADMINISTRASI" dan berhak mengikuti Ujian Tertulis dengan sistem open book pada Hari Kamis, Tanggal 15 Oktober 2020, Mulai Pukul : 08.00 s/d Selesai (waktu setempat) adalah sebagai berikut : II. -

Perkembangan Dan Prospek Partai Politik Lokal Di Propinsi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Diponegoro University Institutional Repository PERKEMBANGAN DAN PROSPEK PARTAI POLITIK LOKAL DI PROPINSI NANGGROE ACEH DARUSSALAM Usulan Penelitian Untuk Tesis Diajukan sebagai salah satu syarat Untuk meraih gelar Magister Ilmu Politik pada Program Pascasarjana Universitas Diponegoro Disusun oleh : MUHAMMAD JAFAR. AW D 4B 006 070 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER ILMU POLITIK PROGRAM PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS DIPONEGORO 2009 ABSTRACTION The Development and Prospect of Local Political Party in Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam As a consequence of the agreement between the Acehnese Freedom Movement (GAM) and Indonesian government, Aceh Province had a very special autonomy which made this province the only one which was allowed to establish a local political party. This special treatment was actually a privilege for this province in order to persuade the GAM to give up their rebellion and come back as the integral part of Indonesian’s Government. Given this background, this thesis tried to examine the development and prospect of this local political party during and after the 2009 election. The main findings of this research were: first of all, there were six local political party which followed as a contestant of the 2009 election: Prosperous and Safety Party (PAAS), The Aceh Sovereignty Party (PDA), The Independent Voice of Acehnese Party (SIRA), Acehnese Party (PRA), Aceh Party (PA) and Aceh United Party (PBA). Second, there were three parties which had strong influence among the six which are PA, PDA and PRA. PA gained its strong influence since it was established by GAM’s exponent, whereas PDA improved its influence to the Islam’s followers in Aceh while PRA was followed by NGO’s activists and academics community. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

134TH COMMENCEMENT James E

134 th Commencement MAY 2021 Welcome Dear Temple graduates, Congratulations! Today is a day of celebration for you and all those who have supported you in your Temple journey. I couldn’t be more proud of the diverse and driven students who are graduating this spring. Congratulations to all of you, to your families and to our dedicated faculty and academic advisors who had the pleasure of educating and championing you. If Temple’s founder Russell Conwell were alive to see your collective achievements today, he’d be thrilled and amazed. In 1884, he planted the seeds that have grown and matured into one of this nation’s great urban research universities. Now it’s your turn to put your own ideas and dreams in motion. Even if you experience hardships or disappointments, remember the motto Conwell left us: Perseverantia Vincit, Perseverance Conquers. We have faith that you will succeed. Thank you so much for calling Temple your academic home. While I trust you’ll go far, remember that you will always be part of the Cherry and White. Plan to come back home often. Sincerely, Richard M. Englert President UPDATED: 05/07/2021 Contents The Officers and the Board of Trustees ............................................2 Candidates for Degrees James E. Beasley School of Law ....................................................3 Esther Boyer College of Music and Dance .....................................7 College of Education and Human Development ...........................11 College of Engineering ............................................................... -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Al-Qur'an Ialah

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Al-Qur’an ialah kitab suci yang merupakan sumber utama bagi ajaran Islam. Melalui al-Qur’an sebagai sumber utama ajaran Islam, manusia mendapatkan petunjuk tentang semua ajaran-ajaran agama Islam. Melalui al- Qur’an pula manusia memperoleh petunjuk tentang semua perintah-perintah dan larangan-larangan Allah SWT yang diturunkan kepada nabi Muhammad SAW untuk disampaikan kepada seluruh umat manusia. Hal ini menunjukkan bahwa kedudukan al-Qur’an sangat penting bagi umat Islam sebagai sumber utama bagi ajaran yang diturunkan oleh Allh SWT. Berdasarkan definisinya, al-Qur’an memiliki arti sebagai kalam Allah SWT yang diturunkan (diwahyukan) kepada Nabi Muhammad SAW melalui perantaraan malaikat Jibril, yang merupakan mukjizat, diriwayatkan secara mutawatir, ditulis dalam sebuah mushaf, dan membacanya adalah sebuah 1 ibadah. Al-Qur’an merupakan mukjizat bagi Nabi Muhammad SAW yang berisi kalam Allah yang penuh dengan pembelajaran berupa hal-hal yang diperintahkan dan dilarang-Nya. Hal-hal yang diperintahkan Allah termaktub seluruhnya dalam al-Qur’an untuk kemudian kewajiban bagi umat Islam 1 Ahmad Syarifuddin, Mendidik Anak Mambaca, Menulis, dan Mencintai Al-Qur’an,( Jakarta: 2004), hal. 16 1 mengerjakan dan mematuhinya seperti, kewajiban bagi umat Islam untuk melaksanakan shalat, zakat, puasa, dan lain-lain. Larangan-larangan dari Allah juga dijelaskan dalam al-Qur’an sebagai rambu-rambu bagi umat Islam dalam bertindak dan berperilaku dalam kehidupannya selama di dunia ini. Larangan- larangan itu misalnya, diharamkannya minum minuman keras, memakan daging babi, melakukan tindak pembunuhan, perjudian dan lain-lain. Al-Qur’an juga sebagai salah satu rahmat yang tak ada taranya bagi alam semesta, karena di dalamnya terkumpul wahyu Ilahi yang menjadi petunjuk, pedoman dan pelajaran bagi siapa yang mempercayai serta mengamalkannya. -

$Tuilia I$Lailiii(A Volume 16, Number 1,2009 INDONESIAN Rcunxn- Ron Tslamlc Studres

$TUilIA I$LAilIII(A Volume 16, Number 1,2009 INDONESIAN rcunxn- ron tsLAMlc sTUDrEs DtsuNIt"y, DlsrnNcr, DISREGARo' THE POLITICAL FAILURE OF ISMVTSU IN LATE CoI-oNnr INooNnsrn Robert E. Elson THB Tno oF IsIAM: CneNc Ho nNo THE LEGACY OF CHINESE MUSLIMS IN PRE-MODERNJAVA Sumanto Al QurtubY THnAucuENTATIoN oF RADICAL lonRs eNo THE ROLE OF ISI-AMIC EOUCNTIONAL SYSTEM IN MALAYSIA Mohd Kamarulnizam Abdullah ISSN 0215-0492 STI]ilIA ISTAilIIKA lndonesian Joumd for lslamic Studies Vol.16. no.1,2009 EDITORIALBOARD: M. Quraish Shihab (UlN lakarta) Taufik Abdullah (LIPI lakarta) Nur A. Fadhil Lubis (IAIN Sumatra Utara) M.C. Ricklefs (Melbourne Uniaersity ) Martin aan Bruinessen (Utrecht Uniztersity) John R. Bowen (Washington Uniuersity, St. Louis) M. Atho Mudzhar (IAIN logyaknrta) M. Kamal Hasan (International lslamic lJniaersity, Kuala Lumpur) M. Bary Hooker (Australian National Uniaersity, Australi.tt) Virginia Matheson Hooker (Australian National Uniaersity, Australin) EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Azyrmardi Azra EDITORS lajat Burhanuddin Saiful Muiani lamhari Fu'ad labali Oman Fathurahma ASSISTANT TO THE EDITORS Ady Setiadi Sulaiman Teslriono ENGLISH LANGUAGE ADVISOR Dickaan der Meij ARABIC LANGUAGE ADVISOR Masri el-MahsyarBidin COVER DESICNER S. Prinkn STUDIA ISLAMIKA (ISSN 021 5-0492) is a journal published by the Center for the study of Islam and society QPIM) lIlN Syarif Hidayatullah, lakarta (sTT DEPPEN No. 129/SK/ bnlfN5ppC/sTi/1976). It specinlizes in Indonesian lslamic studies in particular, and South- east Asian Islamic Studies in general, and is intended to communicate original researches and. current issues on the subject. This journal watmly welcomes contributions from scholars of related disciplines. AII articles published do not necessarily represent the aiews of the journal, or other institutions to which it is affitinted.