Sacred Music Spring 2018 | Volume 145, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Byzantine Coadjutor Archbishop Installed at Cathedral Reflection

Byzantine coadjutor archbishop installed at Cathedral By REBECCA C. M ERTZ I'm com ing back to m y home in Pennsylvania, Before a congregation of some 1800 persons. m arked another milestone in the history of the PITTSBURGH - In am elaborate ceremony where I have so many friends and where I've Archbishop Dolinay, 66, was welcomed into his faith of Byzantine Catholics. Tuesday at St. Paul Cathedral, Byzantine Bishop spent so m uch of m y life," Archbishop Dolinay position w ith the traditional gifts of hospitality, "Today we extend our heartfelt congratula Thom as V. Dolinay of the Van Nuys, Calif., said at the close of the cerem ony. bread, salt and the key. tions to Bishop Dolinay," Archbishop Kocisko Diocese was installed as coadjutor archbishop of As coadjutor. Archbishop Dolinay will have the The papal "bulla" appointing Archbishop said, "as we chart the course of the archdiocese the Byzantine Metropolitan Archdiocese of Pitt right of succession to Archbishop Kocisko. The Dolinay was read, and Archbishop Kocisko through the next m illenium .” sburgh. with Archbishop Stephen J. Kocisko, new archbishop, a native of Uniontown, was or recited the prayer of installation, and led A r During the liturgy that followed the installa the present leader of the Pittsburgh Archdiocese, dained to the episcopate in 1976. Before serving chbishop Dolinay to the throne. tion ceremony, Bishop Daniel Kucera, OSB, a officiating. in California, he was first auxiliary bishop of the In his welcom ing serm on. Archbishop Kocisko form er classmate of Archbishop Dolinay's at St. “I'm overjoyed in this appointment because Passaic, N .J. -

Cloister Chronicle 65

liOISTER+ CnROIDCiiF1 ST. JOSEPH'S PROVINCE The Fathers and Brothers of the Province extend sincere sympathy and prayers to Bro. Patrick Roney, O.P., on the death of his father; to the Rev. T. G. Kinsella, O.P., the Rev. A. B. Dionne, O.P., and Bro. Bonaventure Sauro, O.P., on the death of their mothers; and to Rev. J. B. Hegarty, O.P., the Rev. C. H . McKenna, O.P., and Bro. Raymond Dillon, O.P., on the death of their sisters. From March 3 to 7, a pilgrimage composed of Dominican Fathers, Sisters and members of the Third Order from the United States attended the International Congress of the Third Order of St. Dominic in Rome. The following Fathers accompanied the pilgrimage: the Very Rev. J. B. Walsh, O.P., the Very Rev. W. P. Mcintyre, O.P., the Very Rev. L. P. Johannsen, O.P., the Very Rev. F. H. Dugan, O.P., the Very Rev. P. R. Carroll, O.P., the Rev. P. M. McDermott, O.P., the Rev. W. A. Marchant, O.P., the Rev. J. R. Dooley, O.P., the Rev. E. L. Spence, O.P., the Rev. J. A. Nowlen, O.P., the Rev. L. E. Hughes, O.P., and the Rev. J. B. Logan, O.P. The pilgrimage included a tour of St. Dominic's Country in southern France and a visit to his tomb at Bologna, as well as other points of inter est such as Lourdes, Nevers and Paris. The Rev. P. C. Perrotta, O.P., read a paper on "John Baptist Vico and the Philosophy of History" at the meeting of the American Catholic His torical Association, held in Pittsburgh, Pa., December 28 and 29, 1933. -

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection BOOK NO

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection SUBJECT OR SUB-HEADING OF SOURCE OF BOOK NO. DATE TITLE OF DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT BG no date Merique Family Documents Prayer Cards, Poem by Christopher Merique Ken Merique Family BG 10-Jan-1981 Polish Genealogical Society sets Jan 17 program Genealogical Reflections Lark Lemanski Merique Polish Daily News BG 15-Jan-1981 Merique speaks on genealogy Jan 17 2pm Explorers Room Detroit Public Library Grosse Pointe News BG 12-Feb-1981 How One Man Traced His Ancestry Kenneth Merique's mission for 23 years NE Detroiter HW Herald BG 16-Apr-1982 One the Macomb Scene Polish Queen Miss Polish Festival 1982 contest Macomb Daily BG no date Publications on Parental Responsibilities of Raising Children Responsibilities of a Sunday School E.T.T.A. BG 1976 1981 General Outline of the New Testament Rulers of Palestine during Jesus Life, Times Acts Moody Bible Inst. Chicago BG 15-29 May 1982 In Memory of Assumption Grotto Church 150th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Italy Joannes Paulus PP II BG Spring 1985 Edmund Szoka Memorial Card unknown BG no date Copy of Genesis 3.21 - 4.6 Adam Eve Cain Abel Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.7- 4.25 First Civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.26 - 5.30 Family of Seth Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 5.31 - 6.14 Flood Cainites Sethites antediluvian civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 9.8 - 10.2 Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Ham father of Canaan Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 10.3 - 11.3 Sons of Gomer, Sons of Javan, Sons -

Caecilia V63n10 1936 11.Pdf

Founded A.D. 1874 by John SingenDerger'; • PRINCIPALS AND CLAIMS OF DEVOTIONAL MUSIC Rev. Fr. Joseph Kelly • CESAR AUGUSTE FRANCK Dom Adelard Bouvilliers, 0.5.8. • MSGR. IGNATIUS MITTERER • NEWS FROM EVERYWHERE • Vol. 63 NOVEMBER 1936 No~ ORATEFRATRES A Review Devoted to the Liturgical Apostolate TS first purpose is to foster an intelligent" and whole-hearted participation in I the liturgical life of the Church, which Pius X has called "the primary and indispensable source of the true Christian spirit." Secondarily it also considers the liturgy in its literary, artistic, musical, social, educational and historical aspects. From a Letter Signed By His Eminence Cardinal Gasparri "The Holy Father is greatly pleased that St. John's Abbey is continuing the glorious tradition, and that there is emanating from this abbey an inspiration that tends to elevate. the piety of the faithful by leading them back to the pure fountain of the sacred liturgy." Published every four weeks, beginning with Advent, twelve issues the year. Forty-eight pages. Two dollars the year in the United States. Write for sample copy and descriptive leaflet. THE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville Minnesota DOM DESROQUETTES writes: "So few books,-good books containing the Solesmes teaching, I mean---exist now in English. that I should like to see your book spread everywhere in English--speaking countries," in acknowledging The Gregorian Chant Manual of THE CATHOLIC MUSIC HOUR by The Most Rev. Joseph Schrembs Dom Grego,'y Huegle Sister Alice Marie If your problem is first to teach chant to average school children. and not primarily to picked choir groupst so that they will love it and eagerly take part in congregational singing. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

2010:Frntpgs 2004.Qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai

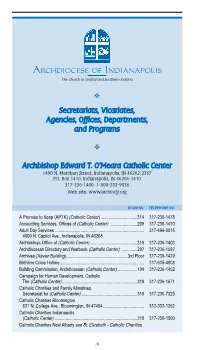

frntpgs_2010:frntpgs_2004.qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai Archdiocese of Indianapolis The Church in Central and Southern Indiana ✜ Secretariats, Vicariates, Agencies, Offices, Departments, and Programs ✜ Archbishop Edward T. O’Meara Catholic Center 1400 N. Meridian Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-2367 P.O. Box 1410, Indianapolis, IN 46206-1410 317-236-1400 1-800-382-9836 Web site: www.archindy.org ROOM NO. TELEPHONE NO. A Promise to Keep (APTK) (Catholic Center) ................................314 317-236-1478 Accounting Services, Offices of (Catholic Center) ........................209 317-236-1410 Adult Day Services .............................................................................. 317-466-0015 4609 N. Capitol Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46208 Archbishop, Office of (Catholic Center)..........................................319 317-236-1403 Archdiocesan Directory and Yearbook (Catholic Center) ..............207 317-236-1587 Archives (Xavier Building)......................................................3rd Floor 317-236-1429 Birthline Crisis Hotline.......................................................................... 317-635-4808 Building Commission, Archdiocesan (Catholic Center)..................104 317-236-1452 Campaign for Human Development, Catholic The (Catholic Center) ..................................................................319 317-236-1571 Catholic Charities and Family Ministries, Secretariat for (Catholic Center)..................................................319 317-236-7325 Catholic Charities Bloomington -

The University of Notre Dame . 1975 Commencement Weekend May16=18

The University of Notre Dame . 1975 Commencement Weekend May16=18 · OFFICIAL _j Events of the Weekend EVENTS OF THE WEEKEND Sunday, May 18 Friday, Saturday and Sunday, May 16, 17 and 18, 1975 10:30 a.m. BOX LUNCH-Available at the North and Except when noted below all ceremonies and activities are to South Dining Halls. (Tickets must be open to the public and tickets are not required. 1 p.m~ purchased in advance.) Friday, May 16 1 p.m. DIPLOMA DISTRIBUTION-Athletic and Convocation Center-North Dome. 6:30 p.m. CONCERT-University Band-Memorial Graduates only. Library Mall. (If weather is inclement, the concert will be 1:35 p.m. ACADEMIC PROCESSION begins cancelled.) Athletic and Convocation Center-North Dome. 8 p.m. MUSICAL---"Man of LaMancha" O'Laughlin Auditoriwn-Saint Mary's 2 p.m. COMMENCEMENT AND CONFER College. (Tickets may be purchased in RING OF DEGREES-Athletic and advance.) Convocation Center-South Dome. 4:30p.m. LAW SCHOOL DIPLOMA Saturday, May 17 CEREMONY-Washington Hall. 10 a.m. ROTC COMMISSIONING-Athletic and Convocation Center-South Dome. 11 a.m. PHI BETA KAPPA Installation-Memorial Library, Auditoriwn. 2 p.m. UNNERSITY RECEPTION-by the to Officers of the University in the Center for 3:30 p.m. Continuing Education. Families of the graduates are cordially invited to attend. 4:30p.m. GRADUATES ASSEMBLE for Academic Procession-Athletic and Convoca tion Center-North Dome. Graduates only. 4:45 p.m. ACADEMIC PROCESSION begins Athletic and Convocation Center-North Dome. 5 p.m. BACCALAUREATE MASS-Athletic and ~~ to Convocation Center-South Dome. -

Il Cardinale Pietro Gasparri Segretario Di Stato (1914–1930)

Lorenzo Botrugno Gasparri ed i rapporti con il Regno Unito nel pontificato di Pio XI Spunti per la ricerca a partire dalle sessioni della Congregazione degli Affari Ecclesiastici Straordinari Abstract Through unpublished documentary sources – the minutes of the meetings of the Sacred Congregation of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs – the essay aims to illustrate Pietro Gasparri’s privileged perspective over anglo-vatican relations. While mainly focused on his period as Cardinal Secretary of State of Pius XI (1922–1930), some hints will also be given to his tenure of office during the pontificate of Benedict XV, as well as to Consalvi’s and Rampolla’s influence on his way of perceiving British matters. Gasparri’s role and at titude will be analysed with particular reference to the negotiations on the appointments of Apostolic Delegates in the British Empire (1926) and the conflict between Church and State in Malta (1928–1932). 1 Introduzione Nel giudizio storiografico la persona e l’opera del Gasparri sono state associate, da sempre, a quella corrente della diplomazia pontificia che si richiama al realismo ed alla flessibilità nella ricerca di intese con gli Stati 1: è dal 1932 che Ernesto Vercesi ne percepì la figura allineata a quella di due suoi predecessori al vertice della Segreteria di Stato, i cardinali Ercole Consalvi e Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro, ognuno dei quali rappresentava natu 1 Tale fu, ad esempio, la percezione di Giovanni Spadolini: “Gasparri era, e restava in ogni atto della sua vita, il grand commis della Chiesa, il grande diplomatico spregiudicato e scettico, armato con tutti i ferri del mestiere ma capace di tutte le duttilità e di tutte le astuzie, pur di servire un fine che egli giudicava essenziale”. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan |

ELLIOTT, William Edward, 1934- * A MODEL FOR THE CENTRALIZATION AND i DECENTRALIZATION OF POLICY AND AEMINISTRATION 1 IN LARGE CATHOLIC DIOCESAN SCHOOL SYSTBtS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 ■J Education, administration u University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan | (&j Copyright by William Edward Elliott I 1971 j A MODEL FOR THE CENTRALIZATION AND DECENTRALIZATION OF POLICY AND ADMINISTRATION IN LARGE CATHOLIC DIOCESAN SCHOOL SYSTEMS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University William Edward Elliott, Ph.B., M.A * * * * * The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Adviser College of Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Doctor Donald P. Anderson, his major adviser, and to the members of his dis sertation committee, Doctors Carl Candoli and Jack R. Frymier, for their invaluable counsel and assistance throughout this study. Special thanks are owed to the experts and to the many public schoolmen, diocesan superintendents, and religious who took time from their busy schedules to read and react to the model proposed in this study. He is especially indebted to Bishops Clarence G. Issenmann and Clarence E. Elwell, at whose request and under whose patronage he began the doctoral program; and to Msgr. Richard E. McHale, the Episcopal Vicar for Education, and Msgr. William N. Novicky, the Diocesan Super intendent of Schools, for their encouragement and support.. He wishes to acknowledge also the warm hospitality of the admin istration and faculty of the Pontifical College Josephinum during hiB years of residency in Columbus, and the thoughtfulness of his colleagues in Cleveland during the final months of the dissertation. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Envisioning Catholicism: Popular Practice of a Traditional Faith in the Post-Wwii Us

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2020 ENVISIONING CATHOLICISM: POPULAR PRACTICE OF A TRADITIONAL FAITH IN THE POST-WWII US Christy A. Bohl University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0884-2280 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.497 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bohl, Christy A., "ENVISIONING CATHOLICISM: POPULAR PRACTICE OF A TRADITIONAL FAITH IN THE POST-WWII US" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--History. 64. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/64 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Sept. 15, 1960 Catholic Church

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall The aC tholic Advocate Archives and Special Collections 9-15-1960 The Advocate - Sept. 15, 1960 Catholic Church Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Catholic Church, "The Advocate - Sept. 15, 1960" (1960). The Catholic Advocate. 131. https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate/131 Sen. Kennedy’s Loyalty Under Fire As Religious Bigotry Boils to Surface By Joe Thomas Nixon, Kennedy’s Republican and “conservative” evangelical stand it in America.” “Citizens for and is Religious Free- which it was Republicans Democrats opponent, equally concerned. church the alleged that the a of Catholic groups, particularly dom” and established study “philoso- sects.” •like are offices in Church nas “running scared” to- His followers fear that Southern “specifically repir- phy” on Church-state anti- Baptist Convention, AND IN Washington, more issues, Dr. Bell chided American because of the a hotel suite here. Rev. Donald diated” the day injection of Catholicism reach such the Churches of Protes- than principle “that “we invited no Catholics into may a Christ, 150 Protestant leaders at H. Gill, Protestants for “soft” a Baptist minister who every man shall being on religious bigotry sugar-coat- that it will tants and other be free to fol- this pitch backfire Americans a “National meeting.” Catholicism. Conference of Cit- became an American citizen in low ed in some instances with the dictates of his de- that disgusted voters will vote United for Separation of Church izens for Freedom" con- Also among the uninvited Religious 1957, was named chairman.