University of Oklahoma Graduate College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations

Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Mark P. Sullivan Specialist in Latin American Affairs November 27, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30981 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Panama: Political and Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations Summary With five successive elected civilian governments, the Central American nation of Panama has made notable political and economic progress since the 1989 U.S. military intervention that ousted the regime of General Manuel Antonio Noriega from power. Current President Ricardo Martinelli of the center-right Democratic Change (CD) party was elected in May 2009, defeating the ruling center-left Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) in a landslide. Martinelli was inaugurated to a five-year term on July 1, 2009. Martinelli’s Alliance for Change coalition with the Panameñista Party (PP) also captured a majority of seats in Panama’s National Assembly. Panama’s service-based economy has been booming in recent years – with a growth rate of 7.6% in 2010 and 10.6% in 2011 – largely because of the ongoing Panama Canal expansion project, now slated for completion in early 2015. The CD’s coalition with the PP fell apart at the end of August 2011when President Martinelli sacked PP leader Juan Carlos Varela as Foreign Minister. Varela, however, retains his position as Vice President. Tensions between the CD and the PP had been growing throughout 2011, largely related to which party would head the coalition’s ticket for the 2014 presidential election. Despite the breakup of the coalition, the strength of the CD has grown significantly since 2009 because of defections from the PP and the PRD and it now has a majority on its own in the legislature. -

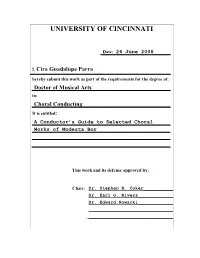

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

A Arte Do “Bem-Morrer”: Ritos, Práticas E Lugares De Purgação No Cariri

ANAIS DO IV ENCONTRO NACIONAL DO GT HISTÓRIA DAS RELIGIÕES E DAS RELIGIOSIDADES – ANPUH - Memória e Narrativas nas Religiões e nas Religiosidades. Revista Brasileira de História das Religiões. Maringá (PR) v. V, n.15, jan/2013. ISSN 1983-2850. Disponível em http://www.dhi.uem.br/gtreligiao/pub.html ____________________________________________________________________________________ Músicos exiliados del nazismo en la Argentina (1932-1943). Aproximaciones sobre sus espacios de acción e inserción Josefina Irurzun * _____________________________________________________________________________ Resumen. Los músicos judíos y antinazis refugiados durante la década del ’30 en Argentina, encontraron en la sociedad receptora, variados ámbitos de expresión más allá de los espacios propios de la comunidad inmigrante organizada. El contexto conservador de la época, la relativa difusión de ideas antisemitas, y las políticas migratorias estatales de corte restrictivo, no condicionaron de manera sólida la recepción e inserción de estos refugiados. La presente comunicación intenta indagar en las experiencias de los músicos refugiados en Argentina a causa de su condición religiosa judía, analizando los espacios asociativos que les proporcionaron oportunidades de inserción, con especial énfasis en el papel que ejerció la Asociación Wagneriana de Buenos Aires. Palabras clave: Exiliados, Nacionalsocialismo, Músicos, Argentina, Asociación Wagneriana Exiled Musicians from Nazi Regime in Argentina (1932-1943). Approaches about their insertion areas. Abstract. Jewish musicians and anti-Nazi refugees during the '30s in Argentina, found in the host society, many areas of expression beyond the spaces of the immigrant community organized. The conservative context in those years, the relative existence of anti-semitic ideas, and migration policies of restrictive cut, did not condition the reception and integration of these refugees. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival

Media contacts Linda Moxley, VP of Marketing & Communications 410.783.8020 [email protected] Devon Maloney, Director of Communications 410.783.8071 [email protected] For Immediate Release Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Announces 2019 New Music Festival Baltimore (April 18, 2019) Under the leadership of Music Director Marin Alsop, the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra (BSO) announces the 2019 New Music Festival. Launched by Alsop and the BSO in 2017, the New Music Festival brings contemporary classical music to Baltimore from June 19-22. The 2019 New Music Festival celebrates women composers ahead of the BSO’s 2019-20 season, which highlights women in music in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in the U.S. Performances include the Baltimore premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Low Brass Concerto, a BSO co- commission, as well as the world premiere of Anna Clyne’s cello concerto, Dance, with Inbal Segev. “I’m thrilled that this year’s New Music Festival features such an outstanding group of contemporary composers, who happen to be women!” said Alsop. “Each piece of music that we’ve programmed tells a unique and compelling story, and we are proud to present a range of voices and perspectives that showcases some of the most inspired work happening in classical composition today.” The 2019 New Music Festival kicks off on Wednesday, June 19 when composer Sarah Kirkland Snider participates in a discussion on her composition process at Red Emma’s Bookstore Café. On Thursday, June 20, Associate Conductor Nicholas Hersh leads members of the BSO and Shara Nova, also known as My Brightest Diamond, in a free concert at the Ottobar. -

Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective Alejandro Marcelo Drago University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Drago, Alejandro Marcelo, "Instrumental Tango Idioms in the Symphonic Works and Orchestral Arrangements of Astor Piazzolla. Performance and Notational Problems: A Conductor's Perspective" (2008). Dissertations. 1107. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved: May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ALEJANDRO MARCELO DRAGO 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. PERFORMANCE AND NOTATIONAL PROBLEMS: A CONDUCTOR'S PERSPECTIVE by Alejandro Marcelo Drago Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2008 ABSTRACT INSTRUMENTAL TANGO IDIOMS IN THE SYMPHONIC WORKS AND ORCHESTRAL ARRANGEMENTS OF ASTOR PIAZZOLLA. -

COURSE NAME: Latin and Caribbean Music

COURSE NAME: Latin and Caribbean Music COURSE NUMBER: MUS*139 CREDITS: 3 CATALOG DESCRIPTION: An introduction to the music of the diverse ethnic groups of the Caribbean and Latin America. The influence of Spain, Africa, Portugal, and other countries on the music of the region will be examined. In addition, the course will explore how the music of the Caribbean and Latin America has made a strong impact abroad. The study will also include how the elements of popular culture, dance, and folk music of the region are interrelated. PREREQUISITES: None COURSE OBJECTIVES: General Education Competencies Satisfied: HCC General Education Requirement Designated Competency Attribute Code(s): None Additional CSCU General Education Requirements for CSCU Transfer Degree Programs: None Embedded Competency(ies): None Discipline-Specific Attribute Code(s): ☒ FINA Fine Arts elective Course objectives: General Education Goals and Outcomes: None Course-Specific Outcomes: 1. Be familiar with the diverse cultures of the Caribbean and Latin America and be able to isolate their characteristics. MUS* E139 Date of Last Revision: April/2017 2. Learn what impact the music and customs of other countries has made on the region. 3. Know the interrelationship between music, art, dance, and other customs. 4. Know the musical instruments and music particular to each area. 5. Be familiar with the history of the region and know how it pertains to music. CONTENT: Introduction A. Overview of the Caribbean and Latin America Heritage of the Caribbean A. The Indian Heritage B. The African Heritage C. The European Heritage D. Other groups: Chinese and Syriansa Creolization A. What is meant by this term and how it affected music. -

Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, Y Las Dos Orillas Del Río De La Plata

Aharonián, Coriún Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Aharonián, Coriún. “Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata” [en línea]. Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” 26,26 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/ayestaran-vega-dos-orillas-rio.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, Buenos Aires, 2012, pág. 203 LAURO AYESTARÁN, CARLOS VEGA, Y LAS DOS ORILLAS DEL RÍO DE LA PLATA CORIÚN AHARONIÁN Resumen El texto explora el diálogo de las dos figuras fundacionales de la musicología de Argentina y Uruguay: de Vega como maestro y Ayestarán como discípulo, y de ambos como amigos. La rica correspondencia que mantuvieran durante casi tres décadas permite recorrer diversas características de sus personalidades, que se centran obsesivamente en el rigor y en la entrega pero que no excluyen el humor y la ternura. Se aportan observaciones acerca de la compleja relación de ambos con otras personalidades del medio musical argentino. -

San Francisco Symphony 2019–2020 Season Concert Calendar

Contact: Public Relations San Francisco Symphony (415) 503-5474 [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / MARCH 12, 2019 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY 2019–2020 SEASON CONCERT CALENDAR PLEASE NOTE: Subscription packages for the San Francisco Symphony’s 2019–20 season go on sale TUESDAY, March 12 at 10 am at www.sfsymphony.org/MTT25, (415) 864-6000, and at the Davies Symphony Hall Box Office, located on Grove Street between Franklin and Van Ness. Discover how to receive free concerts with your subscription package. For additional details and questions visit www.sfsymphony.org/MTT25. All concerts are at Davies Symphony Hall, 201 Van Ness Avenue, San Francisco, unless otherwise noted. OPENING NIGHT GALA Wednesday, September 4, 2019 at 8:00 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor and piano San Francisco Symphony ALL SAN FRANCISCO CONCERT with MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Thursday, September 5, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 7, 2019 at 8 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Alina Ming Kobialka violin Hannah Tarley violin San Francisco Symphony BERLIOZ Overture to Benvenuto Cellini, Opus 23 SAINT-SAËNS Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, Opus 28 RAVEL Tzigane GERSHWIN Second Rhapsody for Orchestra with Piano BRITTEN Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Purcell San Francisco Symphony 2019-20 Season Calendar – Page 2 of 22 SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Thursday, September 12, 2019 at 8 pm Friday, September 13, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 14, 2019 at 8 pm Sunday, September 15, 2019 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor San Francisco Symphony MAHLER Symphony No. 6 in A minor SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY, MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS CONDUCTING Thursday, September 19, 2019 at 2 pm Friday, September 20, 2019 at 8 pm Saturday, September 21, 2019 at 8 pm Sunday, September 22, 2019 at 2 pm Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Daniil Trifonov piano San Francisco Symphony John ADAMS New Work [SFS Co-commission, World Premiere] RACHMANINOFF Piano Concerto No. -

Sociedad Amigos Del Arte De Medellín (1936-1962)

SOCIEDAD AMIGOS DEL ARTE DE MEDELLÍN (1936-1962) LUISA FERNANDA PÉREZ SALAZAR UNIVERSIDAD EAFIT ESCUELA DE CIENCIAS Y HUMANIDADES MAESTRÍA EN MÚSICA 2013 SOCIEDAD AMIGOS DEL ARTE DE MEDELLÍN(1936-1962) LUISA FERNANDA PÉREZ SALAZAR Trabajo de grado presentado como requisito Para optar al título de Magíster en Música Con énfasis en Musicología Histórica Asesor: Dr. Fernando Gil Araque MEDELLÍN UNIVERSIDAD EAFIT DEPARTAMENTO DE MÚSICA 2013 AGRADECIMIENTO Agradezco principalmente a mi asesor, el Doctor Fernando Gil Araque, por su paciencia y su dedicación; gracias a él pude seguir adelante y no perderme en el intento. Sus enseñanzas y su guía, fueron un estímulo para seguir creciendo profesionalmente. Muchísimas gracias a María Isabel Duarte, coordinadora de la Sala de Patrimonio Documental de la Universidad EAFIT. Ella me acogió cordialmente y me brindó toda la ayuda necesaria para acceder a los materiales de consulta. Extiendo el agradecimiento al personal de la Sala Patrimonial, especialmente a Diana y a Luisa, que siempre estuvieron dispuestos a orientarme en mi búsqueda. En Bogotá, quisiera agradecer al personal del Archivo General de la Nación y del Centro de Documentación Musical de la Biblioteca Nacional quienes me abrieron sus puertas y me permitieron indagar en sus archivos por información que fuera útil para mi proyecto. Agradezco especialmente a María Eugenia Jaramillo de Isaza, por abrirme las puertas de su casa y compartir conmigo sus recuerdos y anécdotas sobre la labor de Ignacio Isaza y la Sociedad Amigos del Arte. Finalmente quisiera agradecer a los profesores de la maestría, quienes contribuyeron en mi formación profesional y personal; y a las personas que no nombré, pero que me sirvieron como faro en el camino, y cuyo apoyo fue importante para la culminación de este proyecto de investigación. -

The National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico (Orquesta Sinfonica Nacional De Mexico)

1958 Eightieth Season 1959 UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Charles A. Sink, President Gail W. Rector, Executive Director Lester McCoy, Conductor Fourth Concert Eightieth Annual Choral Union Series Complete Series 3246 The National Symphony Orchestra of Mexico (Orquesta Sinfonica Nacional de Mexico) LUIS HERRERA de la FUENTE, Conductor TUESDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER II, 19S8, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Sensemaya SILVESTRE REVUELTAS Concerto No.2 in F minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 21 CHOPIN Maestoso Larghetto Allegro vivace Soloist: JosE KAHAN INTERMISSION Huapango. JOSE PABLO MONCAYO Symphony No. S, Op. 47 SHOSTAKOVICH Moderato; allegro non troppo Allegretto Largo Allegro non troppo Tlte Steinway is the official piano of the University Musical Society. A R S LON G A V I T A BREVIS PROGRAM NOTES Sensemaya SILVESTRE REVUELTAS The music was composed for a ballet. The theme is a desperate drought in a Caribhean village. A woman announces that Lucero has disappeared, and all go out to search for her. The witch doctor performs his incantations. They encounter a vicious serpent. The men go to get their machetes; the serpent is none other than Lucero, bewitched by the witch doctor. Facundo, suspicious of foul play, tries to stop them. The witch doctor battles with Facundo, wins and slays the serpent, around whose body all execute a dance of triumph. When they go to lift the body, they find it is the body of Lucero. At seeing this, the witch doctor falls, victim of his own spells, and with his death the evil things end. -

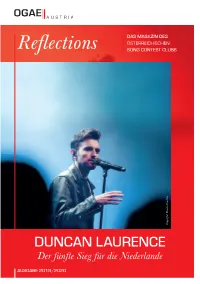

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected]