Emperor's Mercy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mixed Martial Arts

BAB II. REWA FIGHT GYM DAN MIXED MARTIAL ARTS II.1 Pengertian MMA MMA (Mixed Martial Arts) adalah olahraga beladiri campuran yang menggabungkan teknik memukul, menendang, membanting dan mengunci dari beberapa jenis bela diri. MMA Dipromosikan oleh kompetisi global yakni Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) pada tahun 1993, yang dikembangakan oleh Rorion Gracie, John Millius, dan Art Davie. Jenis beladiri yang sering digunakan dalam MMA contohnya Kickoxing, muay thai, karate, taekwondo, judo, jujitsu dan Wrestling. Hal yang menjadi identitas MMA yakni keunggulan teknik beladiri yang rumit untuk melumpuhkan lawan. (sumber: tribunnewswiki.com diakses tanggal 05/12/2020) Gambar II.1.1 Beladiri MMA Sumber: arsip Indosport (diakses pada tanggal 30/042020) II.2 Sejarah MMA MMA sebagai olah raga modern berhubungan dengan sejarah kemunculan kompetisi beladiri, salah satunya adalah UFC. Ultimate Fighting Championship ( UFC ) adalah perusahaan promosi seni bela diri campuran Amerika (MMA) yang berpusat di Las Vegas, Nevada , yang dimiliki dan dioperasikan oleh perusahaan induk William Morris Endeavour . Ini adalah perusahaan promosi MMA terbesar di dunia dan menampilkan beberapa petarung tingkat tertinggi dalam olahraga ini dalam daftar tersebut. UFC memproduksi acara di seluruh dunia yang menampilkan dua belas divisi berat (delapan divisi pria dan empat divisi wanita) dan mematuhi Peraturan Unified of Mixed Martial Arts . Pada 2020, UFC telah mengadakan lebih dari 500 acara . (sumber: https://www.ufc.com/history-ufc diakses pada tanggal 11 april 2020 pukul 12:54) 5 Peserta diperkenakan menggunakan seragam sesuai dengan disiplin bela diri yang didalaminya, bahkan juga diperbolehkan untuk menggunakan satu sarung tinju saja. Pertandingan akan diberhentikan apabila seorang lawan menyerah atau anggota petarung mengibarkan handuk untuk menghentikan pertarungan. -

M a S T E R C a T a L

YOU’LL WEAR IT.TM MASTER CATALOG QUALITY | COMFORT | VALUE “” YOU’LL WEAR IT! STEPHEN ARMELLINO PRESIDENT, CEO THANK YOU FOR YOUR SERVICE. For more than 30 years, we at U.S. Armor have had the honor of outfitting the law enforcement and military communities with superior body armor and protective equipment. As former servicemen, officers or family members of both, myself and our dedicated team members take incredible pride and care in the design and construction of our armor and protective equipment. We are thankful for the opportunity to support you in serving us all. As you know, your armor is only effective if it’s worn and therefore, we have committed ourselves to producing the lightest, safest, and most dynamic armor. It is with your comfort and performance needs in mind that we select the most innovative, respected material suppliers and partners and seek to advance our offerings as applicable. While we solemnly ensure that our products are compliant with all applicable standards and requirements, our primary objective is to protect and support you, so you can focus on effectively doing your job. We thank you for your trust in us and in return, we promise to deliver superior body armor that you’ll comfortably wear. Sincerely, - STEPHEN ARMELLINO A HISTORY TO PROTECT U.S. ARMOR has provided superior body armor and He has taken his father’s protective products for more than three decades. Our designs into the 21st legacy dates back to Richard Armellino, Sr., father of century with U.S. Armor’s current U.S. -

Protective Armor Engineering Design

PROTECTIVE ARMOR ENGINEERING DESIGN PROTECTIVE ARMOR ENGINEERING DESIGN Magdi El Messiry Apple Academic Press Inc. Apple Academic Press Inc. 3333 Mistwell Crescent 1265 Goldenrod Circle NE Oakville, ON L6L 0A2 Palm Bay, Florida 32905 Canada USA USA © 2020 by Apple Academic Press, Inc. Exclusive worldwide distribution by CRC Press, a member of Taylor & Francis Group No claim to original U.S. Government works International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-77188-787-8 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-42905-723-6 (eBook) All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and re- cording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publish- er or its distributor, except in the case of brief excerpts or quotations for use in reviews or critical articles. This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission and sources are indicated. Copyright for individual articles remains with the authors as indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the authors, editors, and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors, editors, and the publisher have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. -

Childrens Syllabus White

Childrens Syllabus White - Pro Blue Revised - March 2019 White (Gloves Recommended) Probation Orange (Nunchakus Required) Progress Check 1 Progress Check 1 Jab Inner Crescent Kick Cross Back Fist Front Kick Jab,Cross,Inner Crescent Kick(Rear)(Adv),Back Fist(Lead) Progress Check 2 Progress Check 2 Roundhouse Kick Back Kick Toes point down to the ground and look at target High Outer Block From horse stance Axe Kick Lower Outer Block From horse stance Jab,Cross,Front Kick(Rear)(St),Back Kick(Lead) Middle Outer Block From horse stance Nunchakus Demonstrate basic control, spinning and strikes Progress Check 3 Progress Check 3 Jab,Cross,Front Kick Combo 3 Jab, Hook(Lead), Cross Jab,Cross,Roundhouse Lower Inner Block From horse stance Jab,Cross,Jab Level Notes - For grading instructors will be testing syllabus from progress check 1 to 3. Combos are Level Notes - Weapons begin as of this level starting with padded Nunchaku. Students must NOT assessed on fluency and sharpness of technique. Students are also assessed on their behaviour and leave weapons laying around and must ask for permission before using them. effort through out the warm up and stretch. Probation Yellow (Gloves Required) Orange (Nunchakus Required) Progress Check 1 Progress Check 1 Hook Punch Body Jab Stationary lead straight punch to body Push Kick Twisting Kick Stand With Guard Stand from the ground without using hands Jab, Cross, Twisting Kick(Rear)(Adv), Body Rip(Rear) Jab,Cross,Hook(Lead),Push Kick(Rear) Progress Check 2 Progress Check 2 Side Thrust Kick Look at target and -

Hand to Hand: Martial Arts ) Aikido ( Revised

( Hand to Hand: Martial Arts ) Aikido ( revised ) Skill Cost: Four "other" skills, or as noted under O.C.C. Skills section. Techniques Known at First Level: Body Block/Tackle (1D6 damage), Body Flip/Throw (2D6 damage), automatic flip/throw, critical flip/throw, breakfall, disarm, roll with punch/fall/impact, pull punch, multiple dodge, automatic parry, kick attack (2D4 damage), and the basic strike, parry and dodge. Locks/Holds: Arm hold, leg hold, body hold, neck hold, wrist lock, arm lock Special Attacks: Knife hand knock-out (Special! The opponent must first be in some sort of joint lock or bound. It does no damage but renders the victim unconscious for 2D4 melees. Requires a normal strike roll), combination automatic parry/strike, combination automatic parry/throw (automatic flip/throw). Modifiers to Attacks: Pull punch, knock-out/stun, automatic flip/throw, critical flip throw, critical strike. Additional Skills (Choose Two): W.P. Knife, W.P. Forked (Sai), W.P. Blunt (Tonfa), W.P. Paired Weapons. Also choose any two domestic or domestic:cultural skills, or Holistic Medicine (any) or Identify Plants & Friuts. Selected skills recieve a +15% skill bonus. Character Bonuses: Add +2D4 to P.P.E. and I.S.P. (if applicable), +2D6 to S.D.C., +1D4 to M.E., +1 to P.P., and +1 to P.E. Level Advancement Bonuses: Level 1: Add two additional attacks per melee, +2 to parry and dodge, +3 to breakfall, +2 to roll with punch/fall/impact, +2 to body flip/throw, critical flip/throw on natural 20 (double damage; 4d6 damage), critical strike on natural 20. -

Complete Krav Maga: the Ultimate Guide to Over 200 Self-Defense

Table of Contents Epigraph Title Page Dedication Foreword What Is Krav Maga? The Roots of the System An Approach Based on Krav Maga Principles Applied to How to Use This Book YELLOW BELT YELLOW BELT - OVERVIEW Fundamentals Combatives Defenses Self-Defense Soft Techniques Groundfighting ORANGE BELT ORANGE BELT - OVERVIEW Combatives Defenses Self-Defense Falls Groundfighting GREEN BELT GREEN BELT - OVERVIEW Combatives Defenses Falls and Rolls Self-Defense Groundfighting BLUE BELT BLUE BELT - OVERVIEW Combatives Defenses Stick Defenses Knife Defenses Gun Defenses Cavaliers Groundfighting Takedowns BROWN BELT BROWN BELT - OVERVIEW Combatives Throws Self-Defense Knife Defenses Shotgun/Assault Rifle/submachine Gun Defenses Gun Defenses INDEX About the Authors and Photographer Copyright Page “Darren Levine is one of a very few people in the world who can critique accomplished Krav Maga instructors, identify pretenders and adapt the Krav Maga system to new circumstances.” —Imi Lichtenfeld, founder of Krav Maga “Darren Levine’s exceptional critical thinking, analytical skills and proficiency in Krav Maga make him one of the best instructors in the world today. This book gives you access to his experience and knowledge.” —Amir Perets, Krav Maga 4th-degree black belt, former hand-to-hand combat instructor for elite units in the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) “An incredibly gifted prosecutor, Darren Levine’s mastery of Krav Maga is equally as effective and deadly as his courtroom skills. Without reservation I strongly recommend this book, and the study of Krav Maga under Darren—there is no finer!” —Scott Reitz, 30-year LAPD/Metro/SWAT officer and head instructor for International Tactical Training Seminars (ITTS) In memory of Marni Foreword by Bas Rutten Hey everybody, listen up: This is El Guapo speaking—Bas Rutten, former UFC heavyweight champion, three-time King of Pancrase, and now spokesperson for the International Fight League. -

Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World

Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis : Weapons of the A ncient World Par t II : Ar mo r an d Mi ss il e We ap on s 1 188.6.65.233 Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World Part 2 , Ar mor an d Missile Weapo ns Versi on 1 .6 4 Codex Ma rtia lis Copyr ig ht 2 00 8, 2 0 09 , 20 1 0, 2 01 1, 20 1 2,20 13 J ean He nri Cha nd ler 0Credits Codex Ma rtia lis W eapons of th e An ci ent Wo rld : Jean He nri Chandler Art ists: Jean He nri Cha nd ler , Reyna rd R ochon , Ram on Esteve z Proofr ead ers: Mi chael Cur l Special Thanks to: Fabri ce C og not of De Tail le et d 'Esto c for ad vice , suppor t and sporad ic fa ct-che cki ng Ian P lum b for h osting th e Co de x Martia lis we bsite an d co n tinu in g to prov id e a dvice an d suppo rt wit ho ut which I nev e r w oul d have publish ed anyt hi ng i ndepe nd ent ly. -

Notes on Arms and Armor

SUV. U5 ; NOTES ON ARMS AND ARMOR THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART NOTES ON ARMS AND ARMOR BY BASHFORD DEAN CURATOR OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ARMS AND ARMOR NEW YORK M C M X V I I. / Z~ PREFACE the field of arms and armor The Metropohtan Museum IiN of Art has hitherto pubhshed four handbooks or cata- logues, viz. : Catalogue of the Loan Collection of Japan- ese Armor (Handbook No. 14), 1903, 71 pp., 14 figs. (Out of Print); Catalogue of European Arms and Armor (Hand- book No. 15), 1905, 215 pp., loi figs. (Out of Print); Catalogue of a Loan Collection of Arms and Armor, 19,1 i, 85 pp., pis. i-xlvii; Handbook of the Collection of Arms and Armor, including the William H. Riggs Donation. 1915. 161 pp., pis. i-lxv [Edition 1, January, Edition II, March]. Together with these appeared from time to time in the Museum Bulletin a series of notes upon various branches of the subject, mainly relating to accessions, but sometimes touching a wider field. Between 1905 and the present year, 19 16, about fifty contributions are recorded, nearly all from the pen of the curator, some brief, some extended. As they were widely scattered, it now seems well to bring them to- gether, with certain changes and additions in both text and figures, together with a hitherto unpublished article, for the use of those who are interested in armor and arms and in the activities of the Museum in this field. Edward Robinson, Director. April, 1916. ioib 1 7 CONTENTS PAGE PAGE I. -

The Samurai Armour Glossary

The Samurai Armour Glossary Ian Bottomley & David Thatcher The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com The Samurai Armour Glossary Nihon-No-Katchu.com Open Library Contributors Ian Bottomley & David Thatcher Editor Tracy Harvey Nihon No Katchu Copyright © January 2013 Ian Bottomley and David Thatcher. This document and all contents. This document and images may be freely shared as part of the Nihon-No-Katchu Open Library providing that it is distributed true to its original format. Illustrations by David Thatcher 2 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com This glossary has been compiled for students of Japanese Armour. Unlike conventional glossaries, this text has been divided into two versions. The first section features terminology by armour component, the second is indexed in alphabetical order. We hope you will enjoy using this valuable resource. Ian & Dave A Namban gusoku with tameshi Edo-Jindai 3 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Contents Armour Makers! 6 Armour for the Limbs! 7 Body Armour! 9 Facial Armour! 16 Helmets! 21 Neck Armour! 28 Applied Decoration! 29 Chain Mail! 30 General Features! 31 Lacing! 32 Materials! 33 Rivets & Hinges! 34 Clothing! 35 Colours! 36 Crests! 36 Historic Periods! 37 Sundry Items! 37 Alphabetical Index! 38 4 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Armour Kabuto Mengu Do Kote Gessan Haidate Suneate A Nuinobe-do gusoku with kawari kabuto Edo-Jindai 5 The Samurai Armour Glossary www.nihon-no-katchu.com Armour Makers Bamen - A small but respected group of armourers that worked during the Muromachi period until the 1700s. -

2018 Product Catalog Contents

2018 PRODUCT CATALOG CONTENTS NIJ STANDARDS & DESIGN • NIJ Standards 0101.06 & 0115.00 3 • Male & Female Vest Design 4 • Tiered Solutions 5 BALLISTICS • HeliX 6 • LiteX 7 • ProX 7 CORRECTIONS • TalonX 8 • Talon 8 CARRIERS • Orion Concealable Carrier [OCC] 10 • Low Profile Concealable Carrier [LPC] 11 • Tactical Response Carrier [TRC] 12 • Tactical Response Carrier Bravo [TRC-B] 12 • Tactical Response Carrier Delta [TRC-D] 12 • Uniform Shirt Carrier [USC] 13 • Uniform Shirt Carrier MOLLE [USC-M] 13 • EMS Carrier [EMS] 14 GH Armor Systems, located in Dover, Tennessee, • APB Carrier [APB] 14 is a leading provider of high-performance • Clean Front Carrier [CFC] 14 protective solutions • Tactical Outer Carrier [TOC] 15 • Quilted Outer Carrier [QOC] 15 to the military, federal • Firearms Instructor Carrier [FIC] 15 and law enforcement TACTICAL communities. With more than 30 years of AD• QU 17 • Velocity Front Opening [VFO] 17 experience, GH offers a comprehensive portfolio • Atlas T3 / T5 / T7 18 of advanced armor solutions that includes • Tactical Plate Harnesses PH1 / PH2 20 concealable, tactical and correctional products • Active Shooter Kits [ASK] 21 • MOLLE Pouches 22 designed for superior wearability and protection. HARD ARMOR All GH Armor Systems products are precision • Special Threat Plates 23 engineered to meet the highest industry • Rifle Plates 24 standards for quality, reliability and safety. • Ballistic Helmets 25 • Ballistic Shields 26 • Riot Helmets / Shields 27 Visit us online for additional information and resources including Online Sizing Submission, Distributor Locator, BVP Application Support, Warranty Registration and more. 2 NIJ STANDARDS NIJ STANDARDS NIJ STANDARDS & DESIGN & DESIGN GH Armor Systems is committed to providing a solution for every threat. -

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2Nd March , 2012

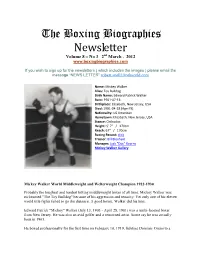

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2nd March , 2012 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] Name: Mickey Walker Alias: Toy Bulldog Birth Name: Edward Patrick Walker Born: 1901-07-13 Birthplace: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Died: 1981-04-28 (Age:79) Nationality: US American Hometown: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7″ / 170cm Reach: 67″ / 170cm Boxing Record: click Trainer: Bill Bloxham Manager: Jack "Doc" Kearns Mickey Walker Gallery Mickey Walker World Middleweight and Welterweight Champion 1922-1930 Probably the toughest and hardest hitting middleweight boxer of all time, Mickey Walker was nicknamed "The Toy Bulldog" because of his aggression and tenacity. Yet only one of his eleven world title fights failed to go the distance. A good boxer, Walker did his best. Edward Patrick "Mickey" Walker (July 13, 1903 - April 28, 1981) was a multi-faceted boxer from New Jersey. He was also an avid golfer and a renowned artist. Some say he was actually born in 1901. He boxed professionally for the first time on February 10, 1919, fighting Dominic Orsini to a four round no-decision in his hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Walker did not venture from Elizabeth until his eighteenth bout, he went to Newark. On April 29 of 1919, he was defeated by knockout in round one by K.O. Phil Delmontt, suffering his first defeat. In 1920, he boxed twelve times, winning two and participating in ten no-decisions. -

Lexique De La Boxe Par Alain Delmas

Page 1 sur 16 LEXIQUE DE LA BOXE PAR ALAIN DELMAS A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z ACTUALISÉ EN AOÛT 2014 C’est une pure coïncidence si ce lexique commence par deux expressions riches de sens : « combattant à terre » et « sens de l’à-propos ». La première expression souligne l'aspect dramatique de la discipline et néanmoins propre au règlement sportif et moment désagréable que l'on ne souhaite à aucun combattant. La seconde expression décrit un savoir-faire* majeur et propre à la capacité à s'adapter* et à exploiter l'activité adverse. Le hasard alphabétique a bien fait les choses et nous pouvons dire qu'avec ces deux expressions, l'entrée en matière dans ce lexique parait réussie. Ce lexique s’achève par la notion de "vitesse" qui de notre avis, est une des dispositions majeures du combattant au même titre que la "prise d'information et l'analyse du jeu adverse", la "stratégie de jeu" et la "puissance de frappe". D’autre part, il s’achève également par l’expression, "Faire le yoyo", histoire de revenir au départ de notre voyage lexical, plus précisément à la situation de "combattant à terre". Bonne lecture à toutes et tous. N.B. : Les termes suivis d’un astérisque sont définis dans ce lexique - L'auteur ne peut pas être tenu responsable des erreurs techniques ou blessures engendrées par une mauvaise interprétation de ce lexique. « Et le monde est au contraire fait d’actes, d’actions (…) des choses concrètes qui cependant passent par la suite, car l’action, cher écrivain, se vérifie, elle a lieu (...) et elle a lieu dans un moment précis, puis elle s’évapore, elle n’est plus, elle fut.