The Southpaw Advantage? - Lateral Preference in Mixed Martial Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Purple Belt Workbook

Purple Belt Workbook Master Robert Adelman Grand Master Jong Hak Yi Hapkido and Taekwondo Techniques Stances: Walking Stance Sitting Stance Back Stance Fighting Stance Power Drill (Basic Drill): Spear hand attack to the throat High section block (fist or knife hand) Outside forearm block (fist or knife hand) Inside forearm block Inner block Low section block Knife hand attack to the throat palm up Palm press block to the side Palm press block down Soft block Punch (High Section, Middle Section, Low Section) High/Middle/Low Basic Walking Drill (Walking, Back and Sitting Stance) ALL PREVIOUS-ADD: Samsumaki Block (Reinforced inner block- two handed block) High Section X Block (Reinforced High Section Block – Fist or Knife hand) Low Section X Block (Reinforced Low Section Block – Fist or Knife hand) High Section Spread Block (Knife hand or Fist) - Can be a block or attack Low Section Spread Block (Knife hand or Fist) - Can be a block or attack Guan-Su-Chirigi - finger attack to the groin. - Walking stance only! U Shape attack to the throat Back Stance (Only for Back stance in Drill) Guarding Block (Knife hand or Fist) Low Section Guarding Block (Knife hand or Fist) Subacan / Soo-Bak-Hand (attack to the groin) U Shape Block (Fist or Knife hand) Sitting Stance (Only for Sitting Stance in Drill) Knife hand strike palm down Knife Hand Strike Palm up Low Section Spread Block (Knife hand / Fist) + Add sidekick Full Mountain Block (fist or knife hand) Half Mountain Block (Fist or knife hand) Kicking Drill: ALL PREVIOUS- ADD: Purple Belt Kicks: Push -

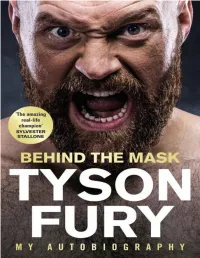

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema JOSH SOPIARZ In Antoine Fuqua’s film Southpaw (2015), just as Jake Gyllenhaal’s character Billy Hope attempts suicide by crashing his luxury sedan into a tree in the front yard, his ten-year-old daughter, Leila, sends him a text message asking: “Daddy. Where are you?” (00:46:04). Her answer comes seconds later when, upon hearing a crash, she finds her father in a heap concussed and bleeding badly on the white marble floor of their home’s entryway. Upon waking, Billy’s first and only concern is Leila. Hospital workers, in an effort to calm him, tell Billy that Leila is safe “with child services” (00:48:08-00:48:10) This news does not comfort Billy. Instead, upon learning that Leila is in the state’s custody, the former light heavyweight champion of the world, with face bloodied and muscles rippling, makes his most concerted effort to get up and leave—presumably, to find his daughter. Before he can rise, however, a doctor administers a large dose of sedative and the heretofore unrestrainable Billy fades into unconsciousness as the scene ends. Leila’s simple question—“Daddy. Where are you?”—is central not only to Southpaw but is also relevant for most major boxing films of the 21st century.1 This includes Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004), David O. Russell’s The Fighter (2010), Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015), Jonathan Jakubowic’s Hands of Stone (2016), and Stephen Caple, Jr.’s Creed II (2018). These films establish fighter/trainer relationships as alternatives to otherwise biological or “traditional” father/son relationships. -

Movement, Space, and Identity in a Mexican Body Culture

societies Article From the Calendar to the Flesh: Movement, Space, and Identity in a Mexican Body Culture George Jennings Cardiff School of Sport and Health Sciences, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff CF23 6XD, UK; [email protected] Received: 20 July 2018; Accepted: 9 August 2018; Published: 13 August 2018 Abstract: There are numerous ways to theorise about elements of civilisations and societies known as ‘body’, ‘movement’, or ‘physical’ cultures. Inspired by the late Henning Eichberg’s notions of multiple and continually shifting body cultures, this article explores his constant comparative (trialectic) approach via the Mexican martial art, exercise, and human development philosophy—Xilam. Situating Xilam within its historical and political context and within a triad of Mesoamerican, native, and modern martial arts, combat sports, and other physical cultures, I map this complexity through Eichberg’s triadic model of achievement, fitness, and experience sports. I then focus my analysis on the aspects of movement in space as seen in my ethnographic fieldwork in one branch of the Xilam school. Using a bare studio as the setting and my body as principle instrument, I provide an impressionist portrait of what it is like to train in Xilam within a communal dance hall (space) and typical class session of two hours (time) and to form and express warrior identity from it. This article displays the techniques; gestures and bodily symbols that encapsulate the essence of the Xilam body culture, calling for a way to theorise from not just from and on the body but also across body cultures. Keywords: body cultures; comparative analysis; Eichberg; ethnography; games; martial arts; Mexico; physical culture; space; theory 1. -

Gary Russell, Patrick Hyland, Jose Pedraza, Stephen Smith

APRIL 16 TRAINING CAMP NOTES: GARY RUSSELL, PATRICK HYLAND, JOSE PEDRAZA, STEPHEN SMITH NEW YORK (April 7, 2016) – The boxers who will be fighting Saturday, April 16 on a SHOWTIME CHAMPIONSHIP BOXING® world title doubleheader are deep into their respective training camps as they continue preparation for their bouts at Foxwoods Resort Casino in Mashantucket, CT. In the main event, live on SHOWTIME® (11 p.m. ET/8 p.m. PT), the talented and speedy southpaw Gary Russell Jr. (26-1, 15 KOs) makes the first defense of his WBC Featherweight World Title against Irish contender Patrick Hyland (31-1, 15 KOs). In the SHOWTIME co-feature, unbeaten sniper Jose Pedraza (21-0, 12 KOs) risks his IBF 130-pound world title as he defends his title for the second time against a mandatory challenger, Stephen Smith (23-1, 13 KOs). Russell, who won the 126-pound title with a fourth-round knockout over defending champion Jhonny Gonzalez on March 28, 2015, trains in Washington, D.C. Hyland, whose only loss suffered was to WBA Super Featherweight World Champion Javier Fortuna, has been training at a gym in Dublin, Ireland, owned and operated by his trainer, Paschal Collins, whose older brother Steve was a former two-time WBO world champion. Paschal Collins also boxed as a pro but is best known for being Irish heavyweight Kevin McBride’s head trainer during his shocking knockout of Mike Tyson. The switch-hitting Pedraza, a 2012 Puerto Rican Olympian, has been working out in his native Puerto Rico. Smith, of Liverpool, England, has been training in the UK. -

Pro Martial Arts Schools Kickboxing Clubs Brown Belt

PRO MARTIAL ARTS SCHOOLS KICKBOXING CLUBS BROWN BELT Padwork Routine 1 Padwork Routine 2 Shield Routine Defensive Routine Sets Freestyle Hand Combinations Freestyle Hand & Kicking Combinations Freestyle Kicking Combinations – Block & Counter Drill 1 to 14 Rear Jump Side Kick Technical Set 5 ((Defender = [ ] )) Left Stance Technical Set 6 ((Defender = [ ] )) Left Stance Rear Round Kick Thigh drop into right stance – [Take Kick to Thigh] – [Right Rear Round Kick Thigh – [Slip Back] – [Right Hook] – Continue turn from Kick Hook] - Leaning Back Guard – Left Round Kick land back into left stance Bobbing under Hook back to left stance [Step Left] - [Left Hook] – Bob & Weave – Right Hook Body Left Hook – [Leaning Back Guard] – [Left Hook] – Leaning Back Guard Technical Set 7 ((Defender = []) Toe to Toe: Attacker Left Stance/ Technical Set 8 ((Defender = []) Toe to Toe: Attacker Right Stance/ Defender Defender Right Left Rear Axe Kick (out to in) landing in Right Stance – [Slip Back with High Right Jab – [Lean Back] – [Jump Rear Round Kick] – Slip to the Right with Side Guard] – Right Hook – [Slip to Right with High Guard] – [Right Jab] – Parry Head Block – Right Hook – [Slip] – Left Hook – [Slip] – Right Uppercut – [Lean [Left Cross] – Parry Back] Technical Set 9 ((Defender = [ ] )) Left Stance Technical Set 10 ((Defender = [ ] )) Left Stance: Defender Against Wall Step in with Power Shin Kick to Thigh – [Take Kick to Thigh] – [Lead Round Right Uppercut Body – [Double Forearm Block] – Left Hook – [Bob & Weave] – Kick to Head] – Left Hook Body -

BA SHI – the Eight Basic Stances the Foundation of Kung Fu by Richard Miller

BA SHI – The Eight Basic Stances The Foundation of Kung Fu By Richard Miller Kung fu (hard work and dedication to a skill over a long period of time), wu shu (martial art), guo shu (Chinese martial art), and ji ji (fighting technique) are all terms frequently used to mean Chinese mar- tial arts. Two terms not so often heard are bai da (bare hand fighting) and chuan yong (possession of brave spirit and martial technique). In Northern China an additional term, ba shi, is used. Aside from ba shi's broad meaning, signifying martial art, is a more specialized reference: The Eight Basic Stances. Author performs deep horse stance in the Chen taiji quan lao jia form It is said that 70% of Northern Chinese kung fu is “leg,” and that 30% is “hand.” It is commonly thought that the 70% refers to kicking. This is a misconception. In fact, the 70% refers to what the Chi- nese call bu, meaning step or footwork. The ba shi is a fundamental tool in training the legs for powerful, decisive footwork. Practicing the ba shi, however, builds not only physical strength, it cultivates qi, and the instrument of mental strength: a calm, patient mind. Sifu Adam Hsu has researched the ba shi. During the more than 20 years of his own martial arts study, he has seen the ba shi taught in many different styles and by many different sifus. He has noticed that only the first six of the eight stances are standard: qi ma shi (horse-riding stance), gong jian shi (bow- and-arrow stance), xi shi (empty-leg stance), pu tui shi (low leg-stretching stance), du li shi (single-leg 1 stance), zuo pan shi (seated-on-own-twisted-leg stance). -

Name: Wally Thom Born: 1926-06-14 Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Birkenhead, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: Click

1 Name: Wally Thom Born: 1926-06-14 Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Birkenhead, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: click The digger you dig into the ring record of Birkenhead Wally Thom the more impressive becomes the fight career of a man who must rank very high on the list of Merseyside’s all time boxing greats. As an amateur he was a junior ABA finalist on two occasions, a senior ABA finalist, was to box internationally against Denmark, reaching the finals of the European Championships in Dublin, and also won a Welsh title. As a professional boxer he suffered greatly from cuts around his eyes in the later stages of his career yet he met and beat some of the top fighters in the world. He reigned as the British and Empire welterweight champion and in a professional career lasting from 1949 to 1956 he won 42 of his 54 contests, with 11 defeats – mostly due to cuts -, and one draw. He was one of the most effective southpaws of all time, yet if the old Birkenhead club trainer Tommy Murray would have had his way Wally would have been an orthodox boxer. Wally’s interest in boxing was stirred by his father who bought him a speed ball from a sports shop in Grange road Birkenhead. “ I had great fun with it but had not thought of taking up boxing until one day at school – Tollemache road , Birkenhead – a teacher called for volunteers to represent the school in the Birkenhead boys championship for the Blake cup. I had a go and won through to the event at Byrne Avenue Swimming Baths, Birkenhead, only to be declared half a stone under the weight required”. -

Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│

Free uniform included with new membership. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│ WWW.MMAOFBOWIE.COM BOWIE MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Member Handbook BRAZILIAN JIU-JITSU │ JUDO │ WRESTLING │ KICKBOXING Copyright © 2019 Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC. All Rights Reserved. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC 2146 PRIEST BRIDGE CT #7, CROFTON, MD 21114, UNITED STATES│ (240) 286-5219│ WWW.MMAOFBOWIE.COM Free uniform included with new membership. Member Handbook Welcome to the world of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. The Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu program consists of a belt ranking system that begins at white belt and progresses to black belt. Each belt level consists of specific techniques in 7 major categories; takedowns, sweeps, guard passes, submissions, defenses, escapes, and combinations. Techniques begin with fundamentals and become more difficult as each level is reached. In addition, each belt level has a corresponding number of techniques for each category. The goal for each of us should be to become a Master, the epitome of the professional warrior. WARNING: Jiu-Jitsu, like any sport, involves a potential risk for serious injury. The techniques used in these classes are being demonstrated by highly trained professionals and are being shown solely for training purposes and competition. Doing techniques on your own without professional instruction and supervision is not a substitute for training. No one should attempt any of these techniques without proper personal instruction from trained instructors. Anyone who attempts any of these techniques without supervision assumes all risks. Bowie Mixed Martial Arts LLC., shall not be liable to anyone for the use of any of these techniques. -

Trends in Capoeira Pedagogy a Thesis Submitted in Partial

CALL AND RESPONSE: TRENDS IN CAPOEIRA PEDAGOGY A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF KINESIOLOGY COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES BY JACKIE BETH SHILCUTT, B.S., B.F.A DENTON, TEXAS AUGUST 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For completion of this project, I would like to acknowledge my sincere thanks to those who have helped make this research process run smoothly and fruitfully. I have tremendously enjoyed this adventure and owe a great deal of gratitude to many people. To all of the participants, thank you for sharing your art, your practices, and your thoughts with me. I immensely enjoyed hearing your stories, sharing in your laughter, and anticipating the future of capoeira. To Dr. David Nichols, thank you for your guidance through the program and the logistics of the research, and thanks to supervising committee members Dr. Lisa Silliman-French and Dr. Leslie Graham for your insights and advice. To Dawn Peterson in the TWU Center for Qualitative Inquiry, thank you for helping me navigate the qualitative research process (and for revealing the Portuguese language function in the software to save countless hours of work time). For linguistic consultation, thank you to Phyllis Gonçalves and Leonardo Marins, whom I must also thank for his transcription services. For medical and cultural insight, thank you to Dra. Karina Brunetti and Dr. Davi de Marco for your interest in this study. Special thanks to Stephanie Talley, Dr. Tracy Shilcutt, and Dr. Kerri Hart for consultation of pedagogical theories and principles. -

Based Application System Design for Pencak Silat Movement Using Support Vector Machines (Svms)

Proceedings of the 5th NA International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Detroit, Michigan, USA, August 10 - 14, 2020 Kinect - Based Application System Design for Pencak Silat Movement using Support Vector Machines (SVMs) Ernest Caesar Omar Syarif, Zener Sukra Lie*, Winda Astuti Automotive and Robotics Engineering Program, Computer Engineering Department BINUS ASO School of Engineering, Bina Nusantara University Jakarta 11480, Indonesia [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Pencak Silat is an Indonesian martial art that has been recognized by UNESCO as a World Cultural Heritage object in 2019. In the practice, it is very difficult to know the accurate movement because no one has control over the movement except with instruction from their coach. Therefore, using Kinect – based study, we developed an application that could estimate body positions compared to stored model positions. By using a skeleton stream which has vector data, we can estimate the angle between two vectors and save it as a reference for further assessment with the user model. In the classification, Support Vector Machines (SVMs) was used which the implementation was done in LabView program. This application has an accuracy rate more than 90% for performing assigned tasks. Keywords Pencak Silat, Support Vector Machine, Kinect, LabVIEW 1. Introduction Pencak Silat is one of the styles of martial arts from Indonesia that have gained traction in the international community, as we can find traces of this style in films and international competitions such as Asian Games. In general, Pencak Silat techniques consists of two important components, that is the basic techniques and the attack techniques. -

Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology

THE SCIENCE OF FOOTWORK The JKD key to defeating any attack By: Ted Wong "The essence of fighting is the art of moving."- Bruce Lee Bruce Lee E-Paper - II Published by - The Wrong Brothers Click Here to Visit our Home page Email - [email protected] Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do Terminology Chinese Name English Translation 1) Lee Jun Fan Bruce Lee’s Chinese Name 2) Jeet Kune Do Way of the Intercepting Fist 3) Yu-Bay! Ready! 4) Gin Lai Salute 5) Bai Jong Ready Position 6) Kwoon School or Academy 7) Si-jo Founder of System (Bruce Lee) 8) Si-gung Your Instructor’s Instructor 9) Si-fu Your Instructor 10) Si-hing Your senior, older brother 11) Si-dai Your junior or younger brother 12) Si-bak Instructor’s senior 13) Si-sook Instructor’s junior 14) To-dai Student 15) Toe-suen Student’s Student 16) Phon-Sao Trapping Hands 17) Pak sao Slapping Hand 18) Lop sao Pulling Hand 19) Jut sao Jerking Hand 20) Jao sao Running Hand 21) Huen sao Circling Hand 22) Boang sao Deflecting Hand (elbow up) 23) Fook sao Horizontal Deflecting Arm 24) Maun sao Inquisitive Hand (Gum Sao) 25) Gum sao Covering, Pressing Hand, Forearm 26) Tan sao Palm Up Deflecting Hand 27) Ha pak Low Slap 28) Ouy ha pak Outside Low Slap Cover 29) Loy ha pak Inside Low Slap Cover 30) Ha o’ou sao Low Outside Hooking Hand 31) Woang pak High Cross Slap 32) Goang sao Low Outer Wrist Block 33) Ha da Low Hit 34) Jung da Middle Hit 35) Go da High Hit 36) Bil-Jee Thrusting fingers (finger jab) 37) Jik chung choi Straight Blast (Battle Punch) 38) Chung choi Vertical Fist 39) Gua choi Back Fist 40)