Education Pack 2018 Not About Heroes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siegfried Sassoon

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry

The Hilltop Review Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring Article 4 June 2017 Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry Rebecca E. Straple Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Preferred Citation Style (e.g. APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) Chicago This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 14 Rebecca Straple Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry “Unburiable bodies sit outside the dug-outs all day, all night, the most execrable sights on earth: In poetry, we call them the most glorious.” – Wilfred Owen, February 4, 1917 Rebecca Straple Winner of the first place paper Ph.D. in English Literature Department of English Western Michigan University [email protected] ANY critics of poetry written during World War I see a clear divide between poetry of the early and late years of the war, usually located after the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Af- ter this event, poetic trends seem to move away from odes Mto courageous sacrifice and protection of the homeland, toward bitter or grief-stricken verses on the horror and pointless suffering of the conflict. This is especially true of poetry written by soldier poets, many of whom were young, English men with a strong grounding in Classical literature and languages from their training in the British public schooling system. -

Ergotherapy and the Doctor Who Cured Wilfred Owen

‘Re-education’, ergotherapy and the doctor who cured Wilfred Owen The end of 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of Wilfred Owen’s war poems being published posthumously.1 A quarter of Owen’s poems and fragments were written or updated in late 1917 when he was a ‘shell-shock’ patient in Edinburgh’s Craiglockhart War Hospital. Here he penned his most remembered verse. Without Craiglockhart and the care of Edinburgh doctor, Dr Arthur John Brock, we may never have read Owen’s words on ‘the pity of war’.2 A century on, Brock’s ‘ergotherapy’ treatments may have resonance and applicability as we care for mental health issues emanating from current global crises. In 1917 Owen saw action in the Somme area of the Western Front. He became a casualty having fallen into a shell hole. Recovering from concussion he was later blown up by a trench mortar and reportedly spent days unconscious. On regaining consciousness, Owen found himself surrounded by the remains of a fellow officer. Owen was transferred to one of the two reception centres for ‘shell-shock’, the Royal Victoria Hospital (the Welsh Hospital, Netley), where he was diagnosed as suffering from ‘war neuroses’ by doctors there. He was then moved to one of Britain’s six ‘shell-shock’ hospitals for officers - Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh. There he was placed under the care of Dr Brock. Brock believed in purging what caused the shock before a programme of ‘re-education’3 whereby patients were returned to normal living and working. This involved ‘ergotherapy’ activities. ‘Ergotherapy’ is the use of physical exertion as a treatment4 or as Brock described it more widely, “cure by functioning.”5 His prescribed activities were both physical and active artistic engagement, stimulating the body and mind. -

[email protected] / 07919 936313 INVERNESS / GLASGOW

[email protected] / 07919 936313 www.kenneth-macleod.com INVERNESS / GLASGOW THE METAMORPHOSIS SET & COSTUME DESIGNER BASED ON THE STORY BY F. KAFKA VANISHING POINT / TRON THEATRE WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY SCOTTISH TOUR / ITALIAN TOUR MATT LENTON 2020 / 2021 RAPUNZEL SCENIC DESIGNER OOR WULLIE SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY JOHNNY MACROBERT ARTS CENTRE WRITTEN BY NOISEMAKER DIRECTED BY DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MCKNIGHT DECEMBER 2019 ANDREW PANTON DECEMBER 2019 KES SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE COOK , THE THIEF, HIS PRODUCTION DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ROBERT ALAN EVANS PERTH THEATRE WIFE & HER LOVER FAENA MIAMI / UNIGRAM DIRECTED BY LU KEMP OCTOBER 2019 WRITTEN BY SCOTT GILMOUR OCTOBER 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON THE DARK CARNIVAL SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE YELLOW IN THE BROOM SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY VANISHING POINT / CITIZENS THEATRE WRITTEN BY ANNE DOWNIE DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MATT LENTON FEBRUARY 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 NOMINATED BEST DESIGN, CRITICS AWARD FOR THEATRE SCOTLAND 2019 BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS VIDEO DESIGNER SPRING AWAKENING SET & COSTUME DESIGNER natIONAL YOUTH BALLET SADLERS WELLS THEATRE SATER / SHEIK ROYAL CONSERVATOIRE / DUNDEE REP DIRTECTED BY MIKAH SMILIE AUGUST 2018 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 THE RETURN SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE OUTSIDER SCENIC/ VIDEO DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ELLIE STEWART EDEN COURT THEATRE, SCOTTISH TOUR KANDER / EBB CUNARD, MS QUEEN ELIZABETH DIRECTED BY PHILLIP HOWARD MARCH 2018 DIRECTED BY TIM WELTON JANUARY 2018 CHICK WHITTINGTON SCENIC -

National Qualifications Curriculum Support

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT English and Communication Using Scottish Texts Support Notes and Bibliographies [MULTI-LEVEL] Edited by David Menzies INTRODUCTION First published 1999 Electronic version 2001 © Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum 1999 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledge this contribution to the Higher Still support programme for English. The help of Gordon Liddell is acknowledged in the early stages of this project. Permission to quote the following texts is acknowledged with thanks: ‘Burns Supper’ by Jackie Kay, from Two’s Company (Blackie, 1992), is reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; ‘War Grave’ by Mary Stewart, from Frost on the Window (Hodder, 1990), is reproduced by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; ‘Stealing’, from Selling Manhattan by Carol Ann Duffy, published by Anvil Press Poetry in 1987; ‘Ophelia’, from Ophelia and Other Poems by Elizabeth Burns, published by Polygon in 1991. ISBN 1 85955 823 2 Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY www.LTScotland.com HISTORY 3 CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction (David Menzies) 1 Section 2: General works and background reading (David Menzies) 4 Section 3: Dramatic works (David Menzies) 7 Section 4: Prose fiction (Beth Dickson) 30 Section 5: Non-fictional prose (Andrew Noble) 59 Section 6: Poetry (Anne Gifford) 64 Section 7: Media texts (Margaret Hubbard) 85 Section 8: Gaelic texts in translation (Donald John MacLeod) 94 Section 9: Scots language texts (Liz Niven) 102 Section 10: Support for teachers (David Menzies) 122 ENGLISH III INTRODUCTION HISTORY 5 INTRODUCTION SECTION 1 Introduction One of the significant features of the provision for English in the Higher Still Arrangements is the prominence given to the study of Scottish language and literature. -

The Impact of the First World War on the Poetry of Wilfred Owen

IIUC STUDIES ISSN 1813-7733 Vol. – 4, December 2007 Published in April 2008 (p 25-40) The impact of the First World War on the poetry of Wilfred Owen Mohammad Riaz Mahmud∗ Abstract: In 1914 the First World War broke out on a largely innocent world, a world that still associated warfare with glorious cavalry charges and the noble pursuit of heroic ideals. This was the world’s first experience of modern mechanized warfare. As the months and years passed, each bringing increasing slaughter and misery, the soldiers became increasingly disillusioned. Many of the strongest protests made against the war were made through the medium of poetry by young men horrified by what they saw. They not only wrote about the physical pain of wounds and deaths, but also the mental pain that were consequences of war. One of these poets was Wilfred Owen. In his poetry we find the feelings of futility, horror, and dehumanization that he encountered in war. World War I broke out on a largely innocent world, a world that still associated warfare with glorious cavalry charges and noble pursuit of heroic ideals. People were wholly unprepared for the horrors of modern trench warfare, and the Great War wiped out virtually a whole generation of young men and shattered so many illusions and ideals. 1 No other war challenged existing conventions, morals, and ideals in the same way as World War I did. World War I saw the mechanization of weapons (heavy artillery, tanks), the use of poison gas, the long stalemate on the Western Front, and trench warfare, all of which resulted in the massive loss of human life. -

An Education Pack to Accompany the Play

An Education Pack to accompany the play Feelgood Theatre Productions Contents Introduction to this Education Pack ............................................ 3 Recommended Resources ........................................................... 4 Not About Heroes – the play ...................................................... 6 Feelgood Theatre Productions .................................................... 7 Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen .......................................... 9 Stephen Macdonald .................................................................. 16 Interview with the Designer ...................................................... 17 A Poet’s Duty ............................................................................. 20 Shellshock ................................................................................. 22 Women and War ....................................................................... 23 2 Not About Heroes Education Pack – © Feelgood Theatre 2014 Introduction to this Education Pack ‘Can the written word purge the soul?’ – Decompression by Mark Gumley This education pack is designed to help anyone wanting to learn or teach about First World War Poetry. It has been created to accompany Feelgood Theatre Productions’ 2014 tour of Not About Heroes, and provides information, teaching resources, and activities about Feelgood’s production, the play itself, War Poetry, and Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. The pack will be most useful for Key Stages 3 & 4. Many of the pages contain activities for -

Not About Heroes

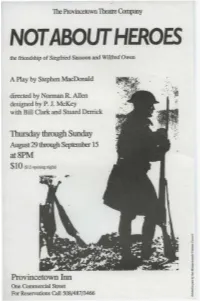

TheProvincetown Theatre Company NOTABOUT HEROES the friendship of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen A Play by Stephen MacDonald directed by Norman R Allen designed by P. J. McKey with Bill Clark and Stuard Derrick Thursdaythrough Sunday August 29through September15 at8PM Provincetown Inn One CommercialStreet P.J. McKEY (Designer): This is P.J.’s first The Provincetown Theatre Company design project with P.T.C. She has designed productions for both college and professional presents theatre including Beckett’s Endgame and Arrabal’s Guernica. Earlier this season P.J. directed Damnee Manon, Sacree Sandra. She Not About Heroes holds an in directing from UMass Amherst MFA the friendship of Siegried Sassoon and has worked with Boston’s AKA Theatre, and Wilfred Owen The Music Theatre Group at the Lenox Arts Center, and the Berkshire Theatre Festival. by Stephen MacDonald P.J.’s next project will be directing Tales of the Lost Formicans for Wellfleet Harbor Actor’s Theatre. Directed by Norman R. Allen Designed by P.J. McKey NORMAN R. ALLEN (Director): Norman made his directing debut last season with The Lisbon Siegfried Sassoon Stuard Derrick Traviata. Cape audiences have seen productions Wilfred Owen Bill Clark or staged-readings of his plays Larry, Queen of Scots, Jenny Saint Joan, Juggling Frank, and Here there will be one ten-minute intermission to Stay. Here to Stay was presented at Playwrights’ Platform in Boston this spring. A freelance writer, Norman’s work has appeared in The American Premiere of Not About Heroes was The Boston Globe, Horizon Magazine, Musical presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, America, The Mindprint Review, Oak Square Nikos Psacharapoulos, Artistic Director. -

THE DEATH and BIRTH of a HERO: the Search for Heroism in British World War One Literature

THE DEATH AND BIRTH OF A HERO: The Search for Heroism in British World War One Literature Cristina Pividori Ph.D. Thesis supervised by Professor Andrew Monnickendam Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2012 Acknowledgments I am heartily thankful to my supervisor, Professor Andrew Monnickendam, who has supported me throughout this thesis with his patience and knowledge while giving me the space to develop my own ideas. One simply could not wish for a better supervisor. I would also like to express my thanks to Professor Debra Kelly of the Group for War and Culture Studies for her generosity in allowing me to spend time at the University of Westminster while developing my research and for her kind and constructive encouragement. Many thanks, too, go to Professor Jay Winter for his insightful, witty remarks. I also owe my gratitude to Dr Jessica Meyer, Dr Santanu Das and the International Society for First World War Studies for patiently replying to my enquiries. For access to World War One original documents, published items and digital resources, I would like to thank the staff of the Humanities Reading Room at the British Library and Mr. Roderick Suddaby and his staff, of the Department of Documents, Imperial War Museum. This research project would not have been possible without the financial support of Generalitat de Catalunya (AGAUR, grants FI-DGR 2007-2010 B-00639 and BE- DGR 2010 A-00870), and the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (grants DCB2005-0181 and TME2009-00547). I am also grateful to my friend Fiona Kelso for her help in proof-reading and for her enthusiastic support. -

The First World War in British Theatre

The First World War in British Theatre Nathan Gregory Finger Macquarie University, Department of English In the Somme valley, the back of language broke. It could no longer carry its former meanings. World War I changed the life of words and images in art, radically and forever. —ROBERT HUGHES This thesis is submitted to Macquarie University in fulfilment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy in English. The work is entirely my own and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination. Signed: Nathan Finger Date: ii Acknowledgments First and foremost thanks must go to Paul for the guidance and advice you gave every step of way, especially in the wayward early days of this project. Without your help I’m quite certain I never would have made it. Second, to the people who endured living with me during this process. Anita, Tom and Angela, that means you guys. You fed me and provided much needed social interaction. But let’s face it, I really am the perfect housemate. My comrade throughout all of this, Jenn. Whenever confusion set in, or things looked dark, or I needed a second opinion on when to use a hyphen, you were always there. I can’t imagine having done this without you. I think it made all the difference. And finally, Mum and Dad, for a hundred thousand reasons that could never be listed. For everything. iii Abstract More than a century since its declaration, the First World War is universally accepted as one of the defining events of the twentieth century. Socially, politically, economically and culturally the war is viewed as having been a watershed and marks the boundary between all facets of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. -

Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon's Critique and Use of Religion In

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 12-2012 The hC urch of Craiglockhart: Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon‘s Critique and Use of Religion in their World War I Poetry Brian Karsten Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Karsten, Brian, "The hC urch of Craiglockhart: Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon‘s Critique and Use of Religion in their World War I Poetry" (2012). Masters Theses. 38. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/38 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Church of Craiglockhart: Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon‘s Critique and Use of Religion in their World War I Poetry Brian Karsten A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts English December 2012 Abstract Throughout history, faith and religious principles have been used as motivation for war. Accordingly, political leaders, religious leaders, and writers all used religion-themed propaganda to encourage enlistment in World War I. Two soldier poets, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, after meeting in the asylum of Craiglockhart, together recognized the injustice represented in using faith to promote warfare. Subsequently, they wrote poetry which criticized the religious and political hierarchy, countered the theology used in propaganda, and attempted to reveal the atrocities in battle. -

The Company the Greenwich Theatre Production 2010

The Company The Greenwich Theatre Production 2010 by John Webster by John Webster In order of appearance Delio Peter Bankolé Antonio Edmund Kingsley Bosola Tim Treloar Cardinal Mark Hadfield Ferdinand Tim Steed Castruccio / Malateste Richard Bremmer Silvio / Officer / Julia's Servant Conrad Westmaas Grisolan / Doctor / Pilgrim / Antonio's Servant James Wallace Duchess Aislin McGuckin Cariola Harvey Virdi Julia / Midwife / Pilgrim Brigid Zengeni Pescara / Second Officer Maxwell Hutcheon All other parts played by members of the company Director Elizabeth Freestone Set and Costume Designer Neil Irish Lighting Designer Wayne Dowdeswell Sound Designer / Composer Adrienne Quartly Associate Director / Movement Stuart Angell Casting Director Ginny Schiller Fight Director Terry King Vocal Coach Cathy Weate Text Consultant Richard Twyman Wardrobe Supervisor Sades Robinson Costume Assistant Kat Cruickshank Dressers Pippa Mawbey, Kat Cruickshank Hair and Make Up Designer Caroline Silk Production Manager Peter Williams Company Stage Manager Jon Swain Deputy Stage Manager Ben Brayshaw Assistant Stage Manager Eleanor Bailey Design Assistant Ross Edwards Props Buyer Susy Payne Technical Assistant Daniel Leman Production Carpenter Rae George Production Intern Sennita Greene Producers James Haddrell / Tim Sawers THE CAST Peter Bankolé Twelfth Night , Without Walls, Drop the Theatre credits include The Dead Donkey , Made in Britain , Peak Caucasian Chalk Circle Practice, (all for Carlton), Sharpes, Doctors (Shared Experience), (BBC) , Dunkirk , Coronation