Ergotherapy and the Doctor Who Cured Wilfred Owen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Wilfred Owen's War Poetry in the Light of Sigmund Freud's Psychoanalytic Theory

An Analysis of Wilfred Owen's War Poetry in the light of Sigmund Freud's Psychoanalytic Theory Berna Köseoğlu Assist.Prof.Dr.Berna Köseoğlu Kocaeli University, Department of English Language and Literature, Kocaeli, Turkey Abstract: World War I influenced not only the lives of “the death of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) at the many people and changed their perspectives towards hands of German machine-gunners in the final week life but also the literary works of the writers and of the Great War has been lamented as one of the altered the tradition in literature. The Poet of World greatest losses in the history of English poetry” [2]. War I, Wilfred Owen, after participating in the army Particularly, the descriptions of the soldiers who lose during the First World War, witnessed the destructive results of the war and produced his poetry regarding their lives during the battles turns out to be his own the terrible outcomes of war when he was a soldier. The tragic end; his own death, in this regard, underlines reflection of war in his poetry proves that he was the reliability and reality of the painful condition of psychologically affected by the war and until his death the soldiers during World War I. in the war, in his poetry, he portrayed how soldiers turned out to be hopeless, helpless, exhausted and In addition, Owen, in his poetry, did not hesitate repressed by the war and why they lost the meaning to criticize implicitly the members of the and joy of life after observing the sufferings of the other government who encouraged the soldiers to join in soldiers and after undergoing a psychological trauma. -

Siegfried Sassoon

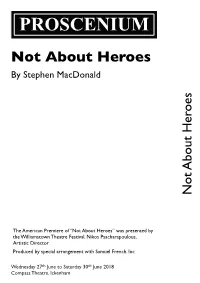

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry

The Hilltop Review Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring Article 4 June 2017 Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry Rebecca E. Straple Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Preferred Citation Style (e.g. APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) Chicago This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 14 Rebecca Straple Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry “Unburiable bodies sit outside the dug-outs all day, all night, the most execrable sights on earth: In poetry, we call them the most glorious.” – Wilfred Owen, February 4, 1917 Rebecca Straple Winner of the first place paper Ph.D. in English Literature Department of English Western Michigan University [email protected] ANY critics of poetry written during World War I see a clear divide between poetry of the early and late years of the war, usually located after the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Af- ter this event, poetic trends seem to move away from odes Mto courageous sacrifice and protection of the homeland, toward bitter or grief-stricken verses on the horror and pointless suffering of the conflict. This is especially true of poetry written by soldier poets, many of whom were young, English men with a strong grounding in Classical literature and languages from their training in the British public schooling system. -

The Poet's Corpus WILFRED OWEN WAS AN

CHARLES HUNTER JOPLIN The Poet’s Corpus Meter, Memory, and Monumentality in Wilfred Owen’s “The Show” The treatment worked: to use one of his favorite metaphors, [Owen] looked into the eyes of the Gorgon and was not turned to stone. In due course the nightmares that might have destroyed him were objectified into poetry. —Dominic Hibberd, Wilfred Owen: A New Biography WILFRED OWEN WAS AN ENGLISH POET who wrote his best work during the autumn of 1917 while recovering from shell shock in Craiglockhart War Hospital for Neurasthenic Officers. Although a few of his poems were published during his short lifetime, Owen died on November 8, 1918 in the Sambre-Oise Canal, before he could publish his book of war poetry. Owen’s body of work was collected by his mother and seven of those poems were edited by Edith Sitwell and published in a special edition of the avant-garde art magazine Wheels: 1919, which was dedicated to the memory of “Wilfred Owen, M.C.” (Stallworthy 81; v.). Following the Wheels edition, Owen’s war poetry spread slowly throughout the Western world. His work appeared in two separate collections in 1920 and 1931, saw widespread circulation during World War II, formed the basis for Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem in 1962, circulated in two more collections in 1963 and 1983, and rose to become a staple of twentieth century poetry anthologies (Stallworthy 81). Although there are other “trench poets” who achieved notoriety after the war’s end, the gradual canonization of Owen’s corpus has entrenched his life and works as a literary monument to our prevailing myths, feelings, and narratives of the First World War.1 Owen’s monumental status in English literature is appropriate because, during his time as a war poet, he carried a monumental mission. -

War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Undergraduate Projects Undergraduate Student Projects Spring 2019 War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One Holly Fleshman Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/undergradproj Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Fleshman, Holly, "War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One" (2019). All Undergraduate Projects. 104. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/undergradproj/104 This Undergraduate Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Student Projects at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Undergraduate Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….. 2 Body………..………………………………………………………………….. 3 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 20 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………….. 24 End Notes ……………………………………………………………………... 28 1 Abstract The military and technological innovations deployed during World War I ushered in a new phase of modern warfare. Newly developed technologies and weapons created an environment which no one had seen before, and as a result, an entire generation of soldiers and their families had to learn to cope with new conditions of shell shock. For many of those affected, poetry offered an outlet to express their thoughts, feelings and experiences. For Great Britain, the work of Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and Robert Graves have been highly recognized, both at the time and in the present. Newspaper articles and reviews published by prominent companies of the time make it clear that each of these poets, who expressed strong opinions and feelings toward the war, deeply influenced public opinion. -

Edward Thomas - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Edward Thomas - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Edward Thomas(3 March 1878 - 9 April 1917) Phillip Edward Thomas was an Anglo-Welsh writer of prose and poetry. He is commonly considered a war poet, although few of his poems deal directly with his war experiences. Already an accomplished writer, Thomas turned to poetry only in 1914. He enlisted in the army in 1915, and was killed in action during the Battle of Arras in 1917, soon after he arrived in France. <b>Early Life</b> Thomas was born in Lambeth, London. He was educated at Battersea Grammar School, St Paul's School and Lincoln College, Oxford. His family were mostly Welsh. Unusually, he married while still an undergraduate and determined to live his life by the pen. He then worked as a book reviewer, reviewing up to 15 books every week. He was already a seasoned writer by the outbreak of war, having published widely as a literary critic and biographer, as well as a writer on the countryside. He also wrote a novel, The Happy-Go-Lucky Morgans (1913). Thomas worked as literary critic for the Daily Chronicle in London and became a close friend of Welsh tramp poet W. H. Davies, whose career he almost single- handedly developed. From 1905, Thomas lived with his wife Helen and their family at Elses Farm near Sevenoaks, Kent. He rented a tiny cottage nearby for Davies and nurtured his writing as best he could. On one occasion, Thomas even had to arrange for the manufacture, by a local wheelwright, of a makeshift wooden leg for Davies. -

[email protected] / 07919 936313 INVERNESS / GLASGOW

[email protected] / 07919 936313 www.kenneth-macleod.com INVERNESS / GLASGOW THE METAMORPHOSIS SET & COSTUME DESIGNER BASED ON THE STORY BY F. KAFKA VANISHING POINT / TRON THEATRE WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY SCOTTISH TOUR / ITALIAN TOUR MATT LENTON 2020 / 2021 RAPUNZEL SCENIC DESIGNER OOR WULLIE SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY JOHNNY MACROBERT ARTS CENTRE WRITTEN BY NOISEMAKER DIRECTED BY DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MCKNIGHT DECEMBER 2019 ANDREW PANTON DECEMBER 2019 KES SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE COOK , THE THIEF, HIS PRODUCTION DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ROBERT ALAN EVANS PERTH THEATRE WIFE & HER LOVER FAENA MIAMI / UNIGRAM DIRECTED BY LU KEMP OCTOBER 2019 WRITTEN BY SCOTT GILMOUR OCTOBER 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON THE DARK CARNIVAL SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE YELLOW IN THE BROOM SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY VANISHING POINT / CITIZENS THEATRE WRITTEN BY ANNE DOWNIE DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MATT LENTON FEBRUARY 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 NOMINATED BEST DESIGN, CRITICS AWARD FOR THEATRE SCOTLAND 2019 BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS VIDEO DESIGNER SPRING AWAKENING SET & COSTUME DESIGNER natIONAL YOUTH BALLET SADLERS WELLS THEATRE SATER / SHEIK ROYAL CONSERVATOIRE / DUNDEE REP DIRTECTED BY MIKAH SMILIE AUGUST 2018 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 THE RETURN SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE OUTSIDER SCENIC/ VIDEO DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ELLIE STEWART EDEN COURT THEATRE, SCOTTISH TOUR KANDER / EBB CUNARD, MS QUEEN ELIZABETH DIRECTED BY PHILLIP HOWARD MARCH 2018 DIRECTED BY TIM WELTON JANUARY 2018 CHICK WHITTINGTON SCENIC -

National Qualifications Curriculum Support

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT English and Communication Using Scottish Texts Support Notes and Bibliographies [MULTI-LEVEL] Edited by David Menzies INTRODUCTION First published 1999 Electronic version 2001 © Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum 1999 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledge this contribution to the Higher Still support programme for English. The help of Gordon Liddell is acknowledged in the early stages of this project. Permission to quote the following texts is acknowledged with thanks: ‘Burns Supper’ by Jackie Kay, from Two’s Company (Blackie, 1992), is reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; ‘War Grave’ by Mary Stewart, from Frost on the Window (Hodder, 1990), is reproduced by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; ‘Stealing’, from Selling Manhattan by Carol Ann Duffy, published by Anvil Press Poetry in 1987; ‘Ophelia’, from Ophelia and Other Poems by Elizabeth Burns, published by Polygon in 1991. ISBN 1 85955 823 2 Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY www.LTScotland.com HISTORY 3 CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction (David Menzies) 1 Section 2: General works and background reading (David Menzies) 4 Section 3: Dramatic works (David Menzies) 7 Section 4: Prose fiction (Beth Dickson) 30 Section 5: Non-fictional prose (Andrew Noble) 59 Section 6: Poetry (Anne Gifford) 64 Section 7: Media texts (Margaret Hubbard) 85 Section 8: Gaelic texts in translation (Donald John MacLeod) 94 Section 9: Scots language texts (Liz Niven) 102 Section 10: Support for teachers (David Menzies) 122 ENGLISH III INTRODUCTION HISTORY 5 INTRODUCTION SECTION 1 Introduction One of the significant features of the provision for English in the Higher Still Arrangements is the prominence given to the study of Scottish language and literature. -

Strange Meeting" Again'

Connotations Vo!. 3.2 (1993/94) "Strange Meeting" Again' DOUGLAS KERR Kenneth Muir's essay "Connotations of 'Strange Meeting''' is a thoughtful and interesting contribution to a discussion that has been going on, in various forms and fora, for the three-quarters of a century since the poem was first published in 1919, the year after Wilfred Owen's death. In the past, "Strange Meeting" has attracted more discussion than any other of Owen's poems (and it remains the only one to have had an entire book written about it).l It is still, arguably, Owen's best-known poem, and from the first it has played a central part in the making and development of Owen's reputation. Prompted by Professor Muir's essay, and to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of this haunting poem's first appearance, I want to sketch here the history of "Strange Meeting" since its publication, and the way the poem has functioned as a focus of debate about Owen and the interpretation of his work. This will bring me back, in a roundabout way, to Professor Muir and some of the points in his essay. A notable absentee from the discussion, unfortunately, is Owen himself. He wrote "Strange Meeting" in the first half of 1918, in that ex- traordinarily creative last year of his life, but there is no mention of the poem in any of his surviving letters. A mere handful of his poems appeared in print in his lifetime, but he had plans for a collection to be called Disabled and Other Poems, and "Strange Meeting" is listed towards the end of two drafts for a table of contents which he drew up in the summer of 1918.2 One of these lists the "motive" of each of the poems he planned to include: the "motive" given for "Strange *Reference: Kenneth Muir, "Connotations of 'Strange Meeting,'" Connotations 3.1 (1993): 26-36. -

Siegfried Sassoon's Record (WO 339/51440

WO 339/51440 Officers’ ‘Long Number Papers’: Siegfried Sassoon 1914-1922 These extracts are taken from the service record of Second Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon who served in the British army during World War One. Siegfried Sassoon was a published poet when he joined the army in 1914. A respected officer, he was awarded the Military Cross in 1916 and served in France and Palestine. Sassoon was invalided out of the war on a number of occasions. During one of his recovery periods back at home, he made contact with a group of pacifists which fuelled his growing disillusionment with the war. In July 1917, Sassoon wrote a letter expressing his anti-war sentiments which was published in The Times and read in the House of Commons, a copy of which is included in this selection. This was a difficult event for military authorities - a respected, decorated, published Officer speaking out publicly against the war - a political nightmare. Sassoon was in danger of being court-martialed, but thanks to an appeal by his friend and fellow poet, Robert Graves, it was accepted that Sassoon’s outburst could be blamed on ‘war neurosis’ and required treatment rather than punishment. He was transferred to Craiglockhart hospital in Edinburgh, where he met the poet Wilfred Owen and developed a close friendship. Both Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon are widely considered to have had relationships with men, although there is no evidence to suggest they were romantically involved with each other. Both Owen and Sassoon produced some of their most famous works while at Craiglockhart together before Owen was killed in action on 4 November 1918 while Sassoon was in England, permanently invalided out of service. -

Year 9 – MODERNISM (Term 2) 1901-1957

Year 9 – MODERNISM (Term 2) The role of women Poetry - themes & context Grammar In the early 19th century women had no place in politics. The suffragettes Attack - Siegfried Sassoon Definition: A began in 1832 & ended in 1918 when parliament passed a bill allowing all Descriptive and confronting poem about the reality of conjunction that is 1901-1957 women over 30 to vote. war. Siegfried Sassoon fought in WW1 himself. The poem being used at the Women had victories but suffered many hardships during this time, even blends a sense of horror with sympathy for the soldiers. Fronted start of a sentence The Modernists were some extremely edgy lads & ladies, who made a point of offending as at the hands of the police who force fed them during their hunger The Dead - Rupert Brooke conjunction such as “But, you many people as they could in order to explore new territory in their work. It isn't surprising that protests. The following people are considered influential to the cause: Describes the lives and experiences of mankind and what we could argue that…” one important journal that published these writers' works was called Blast. Three, two, one, Blast Emily Pankhurst & Millicent Fawcett. will experience after death. The poem begins with the or “And it rang and off: these guys meant to clear out the old as quickly & violently as possible to make way for new Women were presented as dangerous & villainous. The cartoons were description of the kinds of lives that one group of “dead” rang.” ways of seeing & being. particularly vicious. have lived. -

The Impact of the First World War on the Poetry of Wilfred Owen

IIUC STUDIES ISSN 1813-7733 Vol. – 4, December 2007 Published in April 2008 (p 25-40) The impact of the First World War on the poetry of Wilfred Owen Mohammad Riaz Mahmud∗ Abstract: In 1914 the First World War broke out on a largely innocent world, a world that still associated warfare with glorious cavalry charges and the noble pursuit of heroic ideals. This was the world’s first experience of modern mechanized warfare. As the months and years passed, each bringing increasing slaughter and misery, the soldiers became increasingly disillusioned. Many of the strongest protests made against the war were made through the medium of poetry by young men horrified by what they saw. They not only wrote about the physical pain of wounds and deaths, but also the mental pain that were consequences of war. One of these poets was Wilfred Owen. In his poetry we find the feelings of futility, horror, and dehumanization that he encountered in war. World War I broke out on a largely innocent world, a world that still associated warfare with glorious cavalry charges and noble pursuit of heroic ideals. People were wholly unprepared for the horrors of modern trench warfare, and the Great War wiped out virtually a whole generation of young men and shattered so many illusions and ideals. 1 No other war challenged existing conventions, morals, and ideals in the same way as World War I did. World War I saw the mechanization of weapons (heavy artillery, tanks), the use of poison gas, the long stalemate on the Western Front, and trench warfare, all of which resulted in the massive loss of human life.