The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siegfried Sassoon

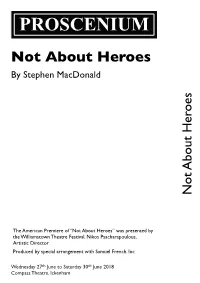

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

Sassoon, Siegfried (1886-1967) by Tina Gianoulis

Sassoon, Siegfried (1886-1967) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Siegfried Sassoon in 1916. The grueling, seemingly endless years of World War I brought a quick education in devastation and futility to hundreds of thousands of young British men, including those who grew up in privilege. One of these was the gay "war poet," Siegfried Sassoon. Brought up in the leisured life of a country gentleman, Sassoon enlisted in the military just as the war was beginning. His poetry reflects the evolution of his attitudes towards war, beginning with a vision of combat as an exploit reflecting glory and nobility, and ending with muddy, bloody realism and bitter recrimination towards those who profited from the destruction of young soldiers. Sassoon came of age during a sort of golden period of Western homosexual intelligentsia, and his friends and lovers were some of the best-known writers, artists, and thinkers of the period. Born on September 8, 1886 in Weirleigh, England, in the county of Kent, Siegfried Louvain (some give his middle name as Loraine, or Lorraine) Sassoon was the son of a Sephardic Jewish father and a Catholic mother. His parents divorced when young Siegfried was five, and his father died of tuberculosis within a few years. While still a teenager, Sassoon experienced his first crush on another boy, a fellow student at his grammar school. He studied both law and history at Clare College, Cambridge, but did not receive a degree. He did, however, meet other gay students at Cambridge, and would later count among his friends such writers associated with Cambridge as his older contemporary E. -

Ergotherapy and the Doctor Who Cured Wilfred Owen

‘Re-education’, ergotherapy and the doctor who cured Wilfred Owen The end of 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of Wilfred Owen’s war poems being published posthumously.1 A quarter of Owen’s poems and fragments were written or updated in late 1917 when he was a ‘shell-shock’ patient in Edinburgh’s Craiglockhart War Hospital. Here he penned his most remembered verse. Without Craiglockhart and the care of Edinburgh doctor, Dr Arthur John Brock, we may never have read Owen’s words on ‘the pity of war’.2 A century on, Brock’s ‘ergotherapy’ treatments may have resonance and applicability as we care for mental health issues emanating from current global crises. In 1917 Owen saw action in the Somme area of the Western Front. He became a casualty having fallen into a shell hole. Recovering from concussion he was later blown up by a trench mortar and reportedly spent days unconscious. On regaining consciousness, Owen found himself surrounded by the remains of a fellow officer. Owen was transferred to one of the two reception centres for ‘shell-shock’, the Royal Victoria Hospital (the Welsh Hospital, Netley), where he was diagnosed as suffering from ‘war neuroses’ by doctors there. He was then moved to one of Britain’s six ‘shell-shock’ hospitals for officers - Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh. There he was placed under the care of Dr Brock. Brock believed in purging what caused the shock before a programme of ‘re-education’3 whereby patients were returned to normal living and working. This involved ‘ergotherapy’ activities. ‘Ergotherapy’ is the use of physical exertion as a treatment4 or as Brock described it more widely, “cure by functioning.”5 His prescribed activities were both physical and active artistic engagement, stimulating the body and mind. -

Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette E

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2017 Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette E. Sebock Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Sebock, Juliette E., "Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War" (2017). Student Publications. 588. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/588 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Abstract Though Robert Graves is remembered primarily for his memoir, Good-bye to All That, his First World War poetry is equally relevant. Comparably to the more famous writings of Sassoon and Owen, Graves' war poems depict the trauma of the trenches, marked by his repressed neurasthenia (colloquially, shell-shock), and foreshadow his later remarkable poetic talents. Keywords Robert Graves, poetry, great war, World War I, shell-shock Disciplines Cultural History | European History | Literature in English, British Isles | Military History Comments Written for HIST 219: The Great War. Creative Commons License Creative ThiCommons works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This student research paper is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ student_scholarship/588 Neurasthenia, Robert Graves, and Poetic Therapy in the Great War Juliette Sebock By 1914, hysterical disorders were easily recognisable, in both civilian and military life. -

War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Undergraduate Projects Undergraduate Student Projects Spring 2019 War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One Holly Fleshman Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/undergradproj Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Fleshman, Holly, "War Poetry: Impacts on British Understanding of World War One" (2019). All Undergraduate Projects. 104. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/undergradproj/104 This Undergraduate Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Student Projects at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Undergraduate Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….. 2 Body………..………………………………………………………………….. 3 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 20 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………….. 24 End Notes ……………………………………………………………………... 28 1 Abstract The military and technological innovations deployed during World War I ushered in a new phase of modern warfare. Newly developed technologies and weapons created an environment which no one had seen before, and as a result, an entire generation of soldiers and their families had to learn to cope with new conditions of shell shock. For many of those affected, poetry offered an outlet to express their thoughts, feelings and experiences. For Great Britain, the work of Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and Robert Graves have been highly recognized, both at the time and in the present. Newspaper articles and reviews published by prominent companies of the time make it clear that each of these poets, who expressed strong opinions and feelings toward the war, deeply influenced public opinion. -

Boston College Collection of Siegfried Sassoon Before 1930-1964 MS.1986.051

Boston College collection of Siegfried Sassoon before 1930-1964 MS.1986.051 https://hdl.handle.net/2345.2/MS1986-051 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 I: Manuscript ............................................................................................................................................... 6 II: Correspondence ...................................................................................................................................... 6 III: Printed works ....................................................................................................................................... -

Private Cooper's War 1918-2018

Private Cooper’s War PRIVATE COOPER’S WAR 1918-2018 Stephen Cooper Copyright Stephen Cooper, 2014 The right of Stephen Cooper to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 1 Private Cooper’s War ARTHUR COOPER 1886-1918 Arthur’s medals and identity disc; and the medallion sent to his widow in 1921 2 Private Cooper’s War For Arthur’s great-great grandsons, William & Toby born 2012 and 2014 3 Private Cooper’s War CONTENTS 1 ‘BLOWN TO BITS’ 2 THE KING’S LIVERPOOL REGIMENT 3 KAISERSCHLACHT, 1918 4 POST-WAR Bibliography Illustrations 4 Private Cooper’s War 1 ‘BLOWN TO BITS’ Links to the Past My grandfather Arthur Cooper (b. 1886) was killed on the Western Front, on or around 12 April 1918. I have two letters about him, written to me by my aunt Peg some 40 years ago, when I was young and she was already old.1 I have no letters written by Arthur himself, nor postcards. Did he write any? The answer may be no, because he was only in France and Flanders a short time, though that would not explain any failure to write home from Norfolk, where he spent some months. Certainly, no letters or postcards have survived; but Paul Fussell’s book The Great War and Modern Memory makes it clear that I am probably not missing much. All letters and postcards written by the troops were censored; and in Old Soldiers Never Die Frank Richards tells how the men were ‘not allowed to say what part of the Front [they] were on, or casualties, or the conditions [they] were living in, or the names of the villages or towns [they] were staying in.’ In any event the Tommies communicated in clichés, partly because - true to the national stereotype - they were phlegmatic; and partly because there was a widely shared view that it didn’t do any good, and certainly didn’t cheer the family up, to complain about one’s lot. -

T. E. Lawrence Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8bg2tr0 No online items T. E. Lawrence Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, April 30, 2009. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2009 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. T. E. Lawrence Papers: Finding mssTEL 1-1277 1 Aid Overview of the Collection Title: T. E. Lawrence Papers Dates (inclusive): 1894-2006 Bulk dates: 1911-2000 Collection Number: mssTEL 1-1277 Creator: Lawrence, T. E. (Thomas Edward), 1888-1935. Extent: 8,707 pieces. 86 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection consists of papers concerning British soldier and author T.E. Lawrence (1888-1935) including manuscripts (by and about Lawrence), correspondence (including over 150 letters by Lawrence), photographs, drawings, reproductions and ephemera. Also included in the collection is research material of various Lawrence collectors and scholars. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Boxes 82-86 -- Coin & Fine Art, Manuscript & Rare Book Dealers. Restricted to staff use only. These boxes include provenance, price and sale information; please see Container List for an item-level list of contents. Publication Rights All photocopies, for which the Huntington does not own the original manuscript, may not be copied in any way, as noted in the Container List and on the folders. -

[email protected] / 07919 936313 INVERNESS / GLASGOW

[email protected] / 07919 936313 www.kenneth-macleod.com INVERNESS / GLASGOW THE METAMORPHOSIS SET & COSTUME DESIGNER BASED ON THE STORY BY F. KAFKA VANISHING POINT / TRON THEATRE WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY SCOTTISH TOUR / ITALIAN TOUR MATT LENTON 2020 / 2021 RAPUNZEL SCENIC DESIGNER OOR WULLIE SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY JOHNNY MACROBERT ARTS CENTRE WRITTEN BY NOISEMAKER DIRECTED BY DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MCKNIGHT DECEMBER 2019 ANDREW PANTON DECEMBER 2019 KES SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE COOK , THE THIEF, HIS PRODUCTION DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ROBERT ALAN EVANS PERTH THEATRE WIFE & HER LOVER FAENA MIAMI / UNIGRAM DIRECTED BY LU KEMP OCTOBER 2019 WRITTEN BY SCOTT GILMOUR OCTOBER 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON THE DARK CARNIVAL SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE YELLOW IN THE BROOM SET & COSTUME DESIGNER WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY VANISHING POINT / CITIZENS THEATRE WRITTEN BY ANNE DOWNIE DUNDEE REP / SCOTTISH TOUR MATT LENTON FEBRUARY 2019 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 NOMINATED BEST DESIGN, CRITICS AWARD FOR THEATRE SCOTLAND 2019 BRIGHT YOUNG THINGS VIDEO DESIGNER SPRING AWAKENING SET & COSTUME DESIGNER natIONAL YOUTH BALLET SADLERS WELLS THEATRE SATER / SHEIK ROYAL CONSERVATOIRE / DUNDEE REP DIRTECTED BY MIKAH SMILIE AUGUST 2018 DIRECTED BY ANDREW PANTON AUGUST 2018 THE RETURN SET & COSTUME DESIGNER THE OUTSIDER SCENIC/ VIDEO DESIGNER WRITTEN BY ELLIE STEWART EDEN COURT THEATRE, SCOTTISH TOUR KANDER / EBB CUNARD, MS QUEEN ELIZABETH DIRECTED BY PHILLIP HOWARD MARCH 2018 DIRECTED BY TIM WELTON JANUARY 2018 CHICK WHITTINGTON SCENIC -

Ts Eliot “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

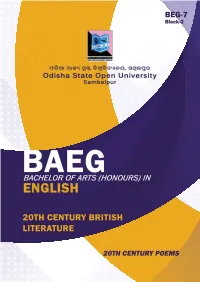

THE COURSE MATERIAL IS DESIGNED AND DEVELOPED BY INDIRA GANDHI NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY (IGNOU), NEW DELHI, OSOU HAS BEEN PERMITTED TO USE THE MATERIAL. BESIDES, A FEW REFERENCES ARE ALSO TAKEN FROM SOME OPEN SOURCES THAT HAS BEEN ACKNOWLEGED IN THE TEXT. BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONOURS) IN ENGLISH (BAEG) BEG-7 20th Century British literature Block-2 20th Century Poems Unit 1 T.S. Eliot “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” Unit 2 W.B. Yeats : “Second Coming” Unit 3 Wilfred Owen: “Strange Meeting” Unit 4 Siegfried Sassoon, “Suicide in The Trenches” UNIT 1: T.S. ELIOT “LOVE SONG OF J. ALFRED PRUFROCK” Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 About T.S. Eliot 1.3 Poem 1.4 Analysis 1.5 Check Your Progress 1.6 Let us Sum up 1.0 OBJECTIVE After reading this poem you will be able to: Examine the tortured psyche of the prototypical modern man—overeducated, eloquent, neurotic, and emotionally stilted. Prufrock, the poem’s speaker, seems to be addressing a potential lover, with whom he would like to “force the moment to its crisis” by somehow consummating their relationship. But Prufrock knows too much of life to “dare” an approach to the woman: In his mind he hears the comments others make about his inadequacies, and he chides himself for “presuming” emotional interaction could be possible at all. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The poem moves from a series of fairly concrete (for Eliot) physical settings—a cityscape (the famous “patient etherised upon a table”) and several interiors (women’s arms in the lamplight, coffee spoons, fireplaces)—to a series of vague ocean images conveying Prufrock’s emotional distance from the world as he comes to recognize his second-rate status (“I am not Prince Hamlet’). -

Masculinity, Repression, and British Patriotism, 1914-1917

1 Masculinity, Repression, and British Patriotism, 1914-1917 Sharon Xiangting Feng Department of History, Barnard College Senior Thesis Seminar Professor Matthew Vaz April 19, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………………..……… 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………..……………….. 4 Chapter One “Athleticism, Masculinity, and Repression” …………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…….. 7 Chapter Two “Masculinity During the War and Further Repression” …………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…….. 15 Chapter Three “Shell-shock and Male Protest” …………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…….. 27 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…….. 39 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………………..………………………….…….. 42 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Matthew Vaz, for all the help and advice along the way and for always being patient despite my constant procrastination. Thank you to Professor Joel Kaye, for introducing me to historical theory and method. Your seminar is among the top 3 of all classes I have taken at Barnard and Columbia. Professor Lisa Tiersten, also my major advisor, thank you for supporting me when I struggled the most in my junior year. I also want to thank Professor Mark Mazower and Professor Susan Pedersen at Columbia, for introducing me to the twentieth century European history and British history in particular. Lastly and most importantly, I would like to thank my parents and my sister, who always provide me with unconditional support and allow me to follow my instinct, even at the times when you have no idea what I am doing. 4 INTRODUCTION When Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, immediate domestic response to the declaration was full of “gaiety and exhilaration.”1 The mobilization for the Great War in Britain was quite unusual. As Adrian Gregory has noted, at the turn of the century, Britain’s strategic interests were mainly in its colonies. -

National Qualifications Curriculum Support

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT English and Communication Using Scottish Texts Support Notes and Bibliographies [MULTI-LEVEL] Edited by David Menzies INTRODUCTION First published 1999 Electronic version 2001 © Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum 1999 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledge this contribution to the Higher Still support programme for English. The help of Gordon Liddell is acknowledged in the early stages of this project. Permission to quote the following texts is acknowledged with thanks: ‘Burns Supper’ by Jackie Kay, from Two’s Company (Blackie, 1992), is reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; ‘War Grave’ by Mary Stewart, from Frost on the Window (Hodder, 1990), is reproduced by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; ‘Stealing’, from Selling Manhattan by Carol Ann Duffy, published by Anvil Press Poetry in 1987; ‘Ophelia’, from Ophelia and Other Poems by Elizabeth Burns, published by Polygon in 1991. ISBN 1 85955 823 2 Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY www.LTScotland.com HISTORY 3 CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction (David Menzies) 1 Section 2: General works and background reading (David Menzies) 4 Section 3: Dramatic works (David Menzies) 7 Section 4: Prose fiction (Beth Dickson) 30 Section 5: Non-fictional prose (Andrew Noble) 59 Section 6: Poetry (Anne Gifford) 64 Section 7: Media texts (Margaret Hubbard) 85 Section 8: Gaelic texts in translation (Donald John MacLeod) 94 Section 9: Scots language texts (Liz Niven) 102 Section 10: Support for teachers (David Menzies) 122 ENGLISH III INTRODUCTION HISTORY 5 INTRODUCTION SECTION 1 Introduction One of the significant features of the provision for English in the Higher Still Arrangements is the prominence given to the study of Scottish language and literature.