Writing War: Owen, Spender, Poetic Forms and Concerns for a World in Turmoil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Poets Anthology

,The War Poets An Anthology if the War Poetry -of the 20th Century . Edited with :an Introduction by Oscar Williams \\ . [, l , The]ohn Day Company • New York Virginia Commonwealth Univers~ty library :,\ " . P/1" I::}J$ Contents COPYRIGHT, 1945, BY OSCAR WILLIAMS W5~" , Introduction 3 All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission. ,,Comments by the Poets. 12 Poems must not be reprinted without permission E. E. Cummings, 12; Geoffrey Grigson, 13; John Mani from the poets, their publishers or theiro agents. fold, 14; Donald Stau!fer, 15; Vernon Watkins, 16; Mark Van Doren, 17; Julian Symons, 17; Richard Eberhart, 18; Henry Treece, 20; Frederic Prokosch, ,21; Selden Rod Second Impression man, 22; Wallace Stevens, 23; Alan Ross, 24; Muriel Rukeyser, '25; Edwin Muir, 26; Karl Shapiro, 26; Hubert Creekmore, 27; Gavin Ewart, 28; John Pudney, 29; John Be"yman,29. , , , ' ;,THOMAS HARDY S POEM ON THE TURN OF THE . I CENTURY: The Darkling Thrush 31 ,'1 THE POETRY OF WORLD WAR I The Pity of It,' by THOMAs HARDY 33 WILFRED OWEN , Greater Love, 35; Arms and the Boy, 35; Inspection, 36; Anthem for Doomed Youth, 36; Dulce Et Decorum Est 37; Exposure, 38; Disabled,. 39; The Show, 40; Memai Cases, 41; Insensibility, 42; A Terre, 44; Strange Meeting 46. ' RUPERT BROOKE The Soldier; 48; The Great Lover, 48. E. E. CUMMINGS I Sing of Olaf, 51; my sweet old etcetera, 52. ROBERT GRAVES Recalling War, 54; Defeat of the Rebels, 55. HERBERT READ The End of a War, 56. -

Statement of Thomas Witt in Opposition to SB 56 House Committee on the Judiciary February 2, 2016

Statement of Thomas Witt In Opposition to SB 56 House Committee on the Judiciary February 2, 2016 Good afternoon Mr. Chairman and members of the committee. I am here today to speak in opposition to SB 56, and I thank you for the opportunity to do so. I am Thomas Witt, Executive Director of Equality Kansas, which works to eliminate discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. However, today I am not speaking on behalf of Equality Kansas. In fact, I am speaking only for myself and my family. My husband is a public school teacher who is certified to teach English, French, and German to middle school and high school students. I have attached to my testimony today a list of 153 books that have been either banned or proposed for ban by activists across the United States. Many of the books on the list before you have been required reading material in courses he has taught. In some cases, he has selected the materials. In others, he has been required to use them in his curriculum. In all cases, the books he has used have been approved by school district and building administration. I have one question for this committee. Whether he’s required to use these titles by his employer, or makes his own selections from approved curricula, which books on this list will send him to jail? That’s all we want to know. How does he do his job without risk of incarceration? Thank you for your time and attention. Title Author A Day No Pigs Would Die Robert Newton Peck A Light in the Attic Shel Silverstein A Prayer for Owen Meany John Irving A Time to Kill John Grisham A Wrinkle in Time Madeleine L’Engle Alice (series) Phyllis Reynolds Naylor Always Running Luis Rodriguez America: A Novel E.R. -

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-Off Things a Little Learning

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-off Things A Little Learning I have not been in a battle; not near one, nor heard one from afar, nor seen the aftermath. I have questioned people who have been in battle - my father and father-in-law among them; have walked over battlefields, here in England, in Belgium, in France and in America; have often turned up small relics of the fighting - a slab of German 5.9 howitzer shell on the roadside by Polygon Wood at Ypres, a rusted anti-tank projectile in the orchard hedge at Gavrus in Normandy, left there in June 1944 by some highlander of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands; and have sometimes brought my more portable finds home with me (a Minie bullet from Shiloh and a shrapnel ball from Hill 60 lie among the cotton-reels in a painted papier-mache box on my drawing-room mantelpiece). I have read about battles, of course, have talked about battles, have been lectured about battles and, in the last four or five years, have watched battles in progress, or apparently in progress, on the television screen. I have seen a good deal of other, earlier battles of this century on newsreel, some of them convincingly authentic, as well as much dramatized feature film and countless static images of battle: photographs and paintings and sculpture of a varying degree of realism. But I have never been in a battle. And I grow increasingly convinced that I have very little idea of what a battle can be like. Neither of these statements and none of this experience is in the least remarkable. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. For more on the Romanticism and Classicism debate in the maga- zines, see David Goldie’s Critical Difference: T. S. Eliot and John Middleton Murry in English Literary Criticism, 1918–1929 (69– 127). Harding’s discussion in his book on Eliot’s Criterion of the same debate is also worth reviewing, especially his chapter on Murry’s The Adelphi; see 25–43. 2. Esty suggests that the “relativization of England as one culture among many in the face of imperial contraction seems to have entailed a relativization of literature as one aspect of culture . [as] the late modernist generation absorbed the potential energy of a contracting British state and converted it into the language not of aesthetic decline but of cultural revival” (8). In a similar fashion, despite Jason Harding’s claim that Eliot’s periodical had a “self-appointed role as a guardian of European civilization,” his extensive study of the magazine, The “Criterion”: Cultural Politics and Periodical Networks in Inter-War Britain, as the title indicates, takes Criterion’s “networks” to exist exclusively within Britain (6). 3. See Suzanne W. Churchill, The Little Magazine Others and the Renovation of Modern American Poetry; Eric White, Transat- lantic Avant-Gardes: Little Magazines and Localist Modernism; Adam McKible, The Space and Place of Modernism: The Russian Revolution, Little Magazines, and New York; Mark Morrisson, The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audience, and Reception, 1905–1920; Faith Binckes, Modernism, Magazines, and the Avant-Garde: Reading “Rhythm,” 1910–1914. 4. Thompson writes, “Making, because it is a study in an active process, which owes as much to agency as to conditioning. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Siegfried Sassoon

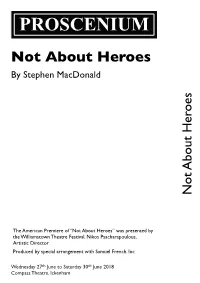

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales

Volume 3 │ Issue 1 │ 2018 The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales McKinley Terry Abilene Christian University Texas Psi Chapter Vol. 3(1), 2018 Article Title: The Bard of the Black Chair: Ellis Evans and Memorializing the Great War in Wales DOI: 10.21081/AX0173 ISSN: 2381-800X Key Words: Wales, poets, 20th Century, World War I, memorials, bards This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Author contact information is available from the Editor at [email protected]. Aletheia—The Alpha Chi Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship • This publication is an online, peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary undergraduate journal, whose mission is to promote high quality research and scholarship among undergraduates by showcasing exemplary work. • Submissions can be in any basic or applied field of study, including the physical and life sciences, the social sciences, the humanities, education, engineering, and the arts. • Publication in Aletheia will recognize students who excel academically and foster mentor/mentee relationships between faculty and students. • In keeping with the strong tradition of student involvement in all levels of Alpha Chi, the journal will also provide a forum for students to become actively involved in the writing, peer review, and publication process. • More information and instructions for authors is available under the publications tab at www.AlphaChiHonor.org. Questions to the editor may be directed to [email protected]. Alpha Chi is a national college honor society that admits students from all academic disciplines, with membership limited to the top 10 percent of an institution’s juniors, seniors, and graduate students. -

W. H. Auden and His Quest for Love Poems of 1930S a Thesis

W. H. Auden and His Quest for Love Poems of 1930s A Thesis Presented to The Graduate School of Language and Culture Hiroshima Jogakuin Unxversity In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree Master of Artぷ by Hiromi Ito January 1998 CONTENTS Intro du ction "1929" II "The Wanderer" 23 Ill "A Summer Night {To Geoffrey Hoyland)〟 from Look, Stranger! 30 IV "0 what Is That Sound〝 from Look, Stranger! 42 "On This Island〝 from Look, Stranger! SB VI " Lullaby" 55 Conclusion . 61 Notes 63 Biblio grap hy 64 Intro duc tio n First of all, the writer would like to introduce a brief survey of W. H. Auden's biography. WysLern Hugh Auden was born on the t∬enty-first of February, 1907. in the city of York in the northern part of England. He is the third and last child of George Augustus Auden and Constance Rosalie Brickenell. They two are devout Chrxstians of the Church of England. Wystern was the youngest of three boys. In 1915, he entered St. Edmund School, where he first met Chrxstopher Isherwood. a colleague of his in his later years. Isherwood was three years ahead of Auden in school. Then he want on to Gresham′s school in Holt, Norfolk. He majored in biology, aiming to be a technical expert. He started to write poems in 1922 when his friend, Robert Medley asked him "Do you want to write a poem?" In 1925. he graduated from Gresham′s school, and then entered Christ Church College, Oxford University. He was an honor student majoring in natural sciences, and later he switched off Lo English literature. -

Tate Papers - the 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h

Tate Papers - The 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/05autumn/walke... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL The 'Comic Sublime': Eileen Agar at Ploumanac'h Ian Walker Fig.1 Eileen Agar 'Rockface', Ploumanach 1936 Black and white photograph reproduced from original negative Tate Archive Photographic Collection 5.4.3 © Tate Archive 2005 On Saturday 4 July 1936, the International Surrealist Exhibition in London came to an end. In that same month, the Architectural Review magazine announced a competition. In April, they had published Paul Nash's article 'Swanage or Seaside Surrealism'.1 Now, in July, the magazine offered a prize for readers who sent in their own surrealist holiday photographs – 'spontaneous examples of surrealism discerned in English holiday resorts'. The judges would be Nash and Roland Penrose .2 At face value, this could be taken as a demonstration of the irredeemable frivolity of surrealism in England (it is difficult to imagine a surrealist snapshot competition in Paris judged by André Breton and Max Ernst ). But in a more positive light, it exemplifies rather well the interest that the English had in popular culture and in pleasure. Holidays were very important in English surrealism and some of its most interesting work was made during them. This essay will examine closely one particular set of photographs made by Eileen Agar in that month of July 1936 which illustrate this relationship between surrealism in England and pleasure. Eileen Agar had been one of the English stars of the surrealism exhibition, even though she had apparently not thought of herself as a 'surrealist' until the organizers of the show – Roland Penrose and Herbert Read – came to her studio and declared her to be one. -

The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry

The Hilltop Review Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring Article 4 June 2017 Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry Rebecca E. Straple Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/hilltopreview Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Preferred Citation Style (e.g. APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) Chicago This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Hilltop Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. 14 Rebecca Straple Glorious and Execrable: The Dead and Their Bodies in World War I Poetry “Unburiable bodies sit outside the dug-outs all day, all night, the most execrable sights on earth: In poetry, we call them the most glorious.” – Wilfred Owen, February 4, 1917 Rebecca Straple Winner of the first place paper Ph.D. in English Literature Department of English Western Michigan University [email protected] ANY critics of poetry written during World War I see a clear divide between poetry of the early and late years of the war, usually located after the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Af- ter this event, poetic trends seem to move away from odes Mto courageous sacrifice and protection of the homeland, toward bitter or grief-stricken verses on the horror and pointless suffering of the conflict. This is especially true of poetry written by soldier poets, many of whom were young, English men with a strong grounding in Classical literature and languages from their training in the British public schooling system. -

Sidney Keyes: the War-Poet Who 'Groped for Death'

PINAKI ROY Sidney Keyes: The War-Poet Who ‘Groped For Death’ f the Second World War (1939-45) was marked by the unforeseen annihilation of human beings—with approximately 60 million military and civilian deaths (Mercatante 3)—the second global belligerence was also marked by an Iunforeseen scarcity in literary commemoration of the all-destructive belligerence. Unlike the First World War (1914-18) memories of which were recorded mellifluously by numerous efficient poets from both the sides of the Triple Entente and Central Powers, the period of the Second World War witnessed so limited a publication of war-writing in its early stages that the Anglo-Irish litterateur Cecil Day-Lewis (1904-72), then working as a publications-editor at the English Ministry of Information, was galvanised into publishing “Where are the War Poets?” in Penguin New Writing of February 1941, exasperatedly writing: ‘They who in folly or mere greed / Enslaved religion, markets, laws, / Borrow our language now and bid / Us to speak up in freedom’s cause. / It is the logic of our times, / No subject for immortal verse—/ That we who lived by honest dreams / Defend the bad against the worse’. Significantly, while millions of Europeans and Americans enthusiastically enlisted themselves to serve in the Great War and its leaders were principally motivated by the ideas of patriotism, courage, and ancient chivalric codes of conduct, the 1939-45 combat occurred amidst the selfishness of politicians, confusing international politics, and, as William Shirer notes, by unsubstantiated feelings of defeatism among world powers like England and France, who could have deterred the offensive Nazis at the very onset of hostilities (795-813). -

Sharpe, Tony, 1952– Editor of Compilation

more information - www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT W. H. Auden is a giant of twentieth-century English poetry whose writings demonstrate a sustained engagement with the times in which he lived. But how did the century’s shifting cultural terrain affect him and his work? Written by distinguished poets and schol- ars, these brief but authoritative essays offer a varied set of coor- dinates by which to chart Auden’s continuously evolving career, examining key aspects of his environmental, cultural, political, and creative contexts. Reaching beyond mere biography, these essays present Auden as the product of ongoing negotiations between him- self, his time, and posterity, exploring the enduring power of his poetry to unsettle and provoke. The collection will prove valuable for scholars, researchers, and students of English literature, cultural studies, and creative writing. Tony Sharpe is Senior Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. He is the author of critically acclaimed books on W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Vladimir Nabokov, and Wallace Stevens. His essays on modernist writing and poetry have appeared in journals such as Critical Survey and Literature and Theology, as well as in various edited collections. W. H. AUDen IN COnteXT edited by TONY SharPE Lancaster University cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521196574 © Cambridge University Press 2013 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press.