The First World War in British Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Littlewood Education Pack in Association with Essentialdrama.Com Joan Littlewood Education Pack

in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan LittlEWOOD Education pack in association with Essentialdrama.com Joan Littlewood Education PAck Biography 2 Artistic INtentions 5 Key Collaborators 7 Influences 9 Context 11 Productions 14 Working Method 26 Text Phil Cleaves Nadine Holdsworth Theatre Recipe 29 Design Phil Cleaves Further Reading 30 Cover Image Credit PA Image Joan LIttlewood: Education pack 1 Biography Early Life of her life. Whilst at RADA she also had Joan Littlewood was born on 6th October continued success performing 1914 in South-West London. She was part Shakespeare. She won a prize for her of a working class family that were good at verse speaking and the judge of that school but they left at the age of twelve to competition, Archie Harding, cast her as get work. Joan was different, at twelve she Cleopatra in Scenes from Shakespeare received a scholarship to a local Catholic for BBC a overseas radio broadcast. That convent school. Her place at school meant proved to be one of the few successes that she didn't ft in with the rest of her during her time at RADA and after a term family, whilst her background left her as an she dropped out early in 1933. But the outsider at school. Despite being a misft, connection she made with Harding would Littlewood found her feet and discovered prove particularly infuential and life- her passion. She fell in love with the changing. theatre after a trip to see John Gielgud playing Hamlet at the Old Vic. Walking to Find Work Littlewood had enjoyed a summer in Paris It had me on the edge of my when she was sixteen and decided to seat all afternoon. -

How to Buy DVD PC Games : 6 Ribu/DVD Nama

www.GamePCmurah.tk How To Buy DVD PC Games : 6 ribu/DVD Nama. DVD Genre Type Daftar Game Baru di urutkan berdasarkan tanggal masuk daftar ke list ini Assassins Creed : Brotherhood 2 Action Setup Battle Los Angeles 1 FPS Setup Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth 1 Adventure Setup Call Of Duty American Rush 2 1 FPS Setup Call Of Duty Special Edition 1 FPS Setup Car and Bike Racing Compilation 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Mater-National Championship 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars Toon: Mater's Tall Tales 1 Racing Simulation Setup Cars: Radiator Springs Adventure 1 Racing Simulation Setup Casebook Episode 1: Kidnapped 1 Adventure Setup Casebook Episode 3: Snake in the Grass 1 Adventure Setup Crysis: Maximum Edition 5 FPS Setup Dragon Age II: Signature Edition 2 RPG Setup Edna & Harvey: The Breakout 1 Adventure Setup Football Manager 2011 versi 11.3.0 1 Soccer Strategy Setup Heroes of Might and Magic IV with Complete Expansion 1 RPG Setup Hotel Giant 1 Simulation Setup Metal Slug Anthology 1 Adventure Setup Microsoft Flight Simulator 2004: A Century of Flight 1 Flight Simulation Setup Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian 1 Action Setup Naruto Ultimate Battles Collection 1 Compilation Setup Pac-Man World 3 1 Adventure Setup Patrician IV Rise of a Dynasty (Ekspansion) 1 Real Time Strategy Setup Ragnarok Offline: Canopus 1 RPG Setup Serious Sam HD The Second Encounter Fusion (Ekspansion) 1 FPS Setup Sexy Beach 3 1 Eroge Setup Sid Meier's Railroads! 1 Simulation Setup SiN Episode 1: Emergence 1 FPS Setup Slingo Quest 1 Puzzle -

Prince All Albums Free Download Hitnrun: Phase Two

prince all albums free download HITnRUN: Phase Two. Following quickly on the heels of its companion, HITnRUN: Phase Two is more a complement to than a continuation of its predecessor. Prince ditches any of the lingering modern conveniences of HITnRUN: Phase One -- there's nary a suggestion of electronics and it's also surprisingly bereft of guitar pyrotechnics -- in favor of a streamlined, even subdued, soul album. Despite its stylistic coherence, Prince throws a few curve balls, tossing in a sly wink to "Kiss" on "Stare" and opening the album with "Baltimore," a Black Lives Matter protest anthem where his outrage is palpable even beneath the slow groove. That said, even the hardest-rocking tracks here -- that would be the glammy "Screwdriver," a track that would've been an outright guitar workout if cut with 3rdEyeGirl -- is more about the rhythm than the riff. Compared to the relative restlessness of HITnRUN: Phase One, not to mention the similarly rangy Art Official Age, this single-mindedness is initially overwhelming but like any good groove record, HITnRUN: Phase Two winds up working best over the long haul, providing elegant, supple mood music whose casualness plays in its favor. Prince isn't showing off, he's settling in, and there are considerable charms in hearing a master not trying so hard. Prince all albums free download. © 2021 Rhapsody International Inc., a subsidiary of Napster Group PLC. All rights reserved. Napster and the Napster logo are registered trademarks of Rhapsody International Inc. Napster. Music Apps & Devices Blog Pricing Artist & Labels. About Us. Company Info Careers Developers. -

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate

The History/Literature Problem in First World War Studies Nicholas Milne-Walasek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Nicholas Milne-Walasek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT In a cultural context, the First World War has come to occupy an unusual existential point half- way between history and art. Modris Eksteins has described it as being “more a matter of art than of history;” Samuel Hynes calls it “a gap in history;” Paul Fussell has exclaimed “Oh what a literary war!” and placed it outside of the bounds of conventional history. The primary artistic mode through which the war continues to be encountered and remembered is that of literature—and yet the war is also a fact of history, an event, a happening. Because of this complex and often confounding mixture of history and literature, the joint roles of historiography and literary scholarship in understanding both the war and the literature it occasioned demand to be acknowledged. Novels, poems, and memoirs may be understood as engagements with and accounts of history as much as they may be understood as literary artifacts; the war and its culture have in turn generated an idiosyncratic poetics. It has conventionally been argued that the dawn of the war's modern literary scholarship and historiography can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s—a period which the cultural historian Jay Winter has described as the “Vietnam Generation” of scholarship. -

Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain by Benjamin Zenas Cannon Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Prof

Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Kent Puckett Professor Andrew Shanken Spring 2014 Disappearing Walls: Literature and Architecture in Victorian Britain © 2014 By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Abstract Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Prof. Ian Duncan, Chair From Discipline and Punish and The Madwoman in the Attic to recent work on urbanism, display, and material culture, criticism has regularly cast nineteenth-century architecture not as a set of buildings but as an ideological metastructure. Seen primarily in terms of prisons, museums, and the newly gendered private home, this “grid of intelligibility” polices the boundaries not only of physical interaction but also of cultural values and modes of knowing. As my project argues, however, architecture in fact offered nineteenth-century theorists unique opportunities to broaden radically the parameters of aesthetic agency. A building is generally not built by a single person; it is almost always a corporate effort. At the same time, a building will often exist for long enough that it will decay or be repurposed. Long before literature asked “what is an author?” Victorian architecture theory asked: “who can be said to have made this?” Figures like John Ruskin, Owen Jones, and James Fergusson radicalize this question into what I call a redistribution of intention, an ethically charged recognition of the value of other makers. -

Siegfried Sassoon

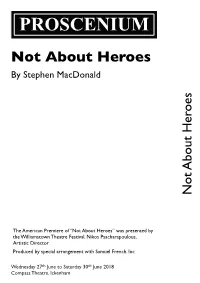

PROSCENIUM Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Not About Heroes About Not The American Premiere of “Not About Heroes” was presented by the Williamstown Theatre Festival, Nikos Psacharapoulous, Artistic Director Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc Wednesday 27th June to Saturday 30th June 2018 Compass Theatre, Ickenham Not About Heroes By Stephen MacDonald Siegfried Sassoon ..................................................... Ben Morris Wilfred Owen .................................................... James Stephen Directed by ........................................................ Richard Kessel Stage Manager .................................................. Keith Cochrane Assisted By ...................................................... Crystal Anthony Technical Assistance ....................................... Charles Anthony Lighting Operation ................................................ Roger Turner Sound Operation ................................................Richard Kessel The Action From a room in Sassoon’s country house in Wiltshire, late at night on 3rd November 1932, Sassoon re-lives incidents that happened between August 1917 and November 1918. In sequence they take place in: • A quiet corner of the Conservative Club in Edinburgh (3rd November 1917) • Two rooms in the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Nervous Disorders, Edinburgh (August-October 1917) • The countryside near Milnathort, Scotland (October 1917) • Owen’s room in Scarborough, Yorkshire (January 1918) • Sassoon’s room in the American -

Download Original 5.98 MB

MAUY HEMENWAY HALL WELLESLEY, MASS., FEBRUARY 26, 1942 D~ Hu Shih To Address 1942 President's Wife·. Senate· Approves Plans For · · E . Outlines College At Commencement xerc1ses Role In Defense New College Radio Station __________.......__<e> Studio to Broadcast From Cbina Ambassador To Talk~ Mrs. Fl'ilnklin D. Roosevelt, who On Anniversary of Mme. Liliom Promises is to speak at Wellesley March 27 Pendleton Hall to All Chiang Kai-shek, '17 Dramatic Triumph during Forum's intercollegiate con Campus Dormitories ference, has issued the following Members of the class of 1942 statement to undergraduates: The College Senate took official will leave Wellesley twenty-five What -could be better spring action in a meeting Monday eve "The role of the colleg·e student years after the graduation of tonic than Spring Formals? ning, February 23, to approve in Civilian Defense is extremely plans, presented by Rosam.rnd Wil Madame Chiang Kai Shek. To em- Barnswallows' final production of important. As far as possible, it phasize her connection with Wel- fley '42, for establishing a Tadio seems to me there should be a lesley the peaker at the com the season, Franz Molnar's Liliom, station at Wellesley. One of forty duplication on the campuses of all mencement exercises this June complete with a Wellesley-Harvard colleges belonging to the network the services which would be re will be His Excellency, DL Hu of the Intercollegiate Broadcasting cast and more of Mr. Daniel Sat- quired of a citizen in his commu Shih, Ambassador from China System, the new • station will be to ler's famous scenery, including an nity, so that on the campus the the United States. -

July 1914: BEFORE IT’S TOO LATE…

JULY 2014 YEAR VI NUMBER 7 The memory of the Great War still creates a divide. understand the July crisis: for both Germany and acquisition of new territories, but also as regards And that’s not all: even one hundred years later, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, “taking the risk was economic and commercial relations. the events in July 2014 remain a historiographical rational” because both Empires felt the urgency of The Septemberprogramm was the manifesto of problem for scholars. Talking about the outbreak solving a strategic dilemma, by striking first, before the German hegemony over Europe. It reads: of WW1 with Gian Enrico Rusconi was not only it was too late. For the centuries-old Habsburg “A Central European economic association is a privilege and honour for us at Telos, it was a monarchy, humiliating Serbia meant not only to be constructed through common customs unique opportunity to review some of the issues reaping an advantage from stabilising the Balkans, agreements, to comprise France, Belgium, Holland, and try to find our way among so many possible it also meant attacking Slavic nationalism, forcefully Denmark, Austria-Hungary, Poland and possibly interpretations. The chain of events which a month protected by Russia, which the Austrians regarded Italy, Sweden and Norway. This association will after the assassination of the heir to the Austro- as a threat to the very survival of their empire. From have no common constitutional supreme authority Hungarian throne led to the involvement of all the their side, the Germans considered their support and will provide for ostensible equality among its great powers in Europe was avoidable. -

Prince Sign "O" the Times Mp3, Flac, Wma

Prince Sign "O" The Times mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul / Pop Album: Sign "O" The Times Country: Europe Released: 1987 Style: Synth-pop, Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1138 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1181 mb WMA version RAR size: 1255 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 234 Other Formats: WMA MOD AAC TTA MIDI RA MPC Tracklist A1 Sign "O" The Times 5:02 A2 Play In The Sunshine 5:05 A3 Housequake 4:38 A4 The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker 4:04 B1 It 5:10 B2 Starfish And Coffee 2:51 B3 Slow Love 4:18 B4 Hot Thing 5:39 B5 Forever In My Life 3:38 C1 U Got The Look 3:58 C2 If I Was Your Girlfriend 4:54 C3 Strange Relationship 4:04 C4 I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man 6:31 D1 The Cross 4:46 D2 It's Gonna Be A Beautiful Night 8:59 D3 Adore 6:29 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – NPG Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – NPG Records Licensed To – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Published By – Controversy Music Recorded At – Paisley Park Studios Recorded At – Sunset Sound Recorded At – Dierks Studio Mobile Trucks Mastered At – Cohearent Audio Pressed By – Record Industry – 16823 Credits Arranged By [Strings] – Claire Fischer* (tracks: B3) Arranged By, Composed By, Performer, Producer – Prince Art Direction – Laura LiPuma Drums – Sheila E. (tracks: C1) Engineer – Coke Johnson, Prince, Susan Rogers Guitar – Wendy* (tracks: B3) Lead Guitar – Mico Weaver (tracks: D2) Lead Vocals – Camille (tracks: A3, C2, C3) Lead Vocals [Co-lead Voice] – Jill Jones (tracks: D2), Susannah (tracks: D2) Lyrics By [Co-written] – Carole Raphaell Davis* (tracks: B3), Susannah (tracks: B2) Mastered By [Originally Mastered By] – Bernie Grundman Mastered By [Vinyl] – KPG@CA* Music By [Co-written] – Dr. -

J. M. Barrie's Literary Approach to Adolescent Psychology

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1947 J. M. Barrie's Literary Approach to Adolescent Psychology Richard F. Burnham Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Burnham, Richard F., "J. M. Barrie's Literary Approach to Adolescent Psychology" (1947). Master's Theses. 81. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1947 Richard F. Burnham J. M. BARRRIE'S LITERARY APPROACH TO ADOLESCENT PSYCHOLOGY BY RIC~AP~ F. BURNHAM, S.J. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FtJLFILLMENT OF THE REQ'CTREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOY0LA tJNIVERSITY AUGUST 1947 VITA AUCTORIS Richard Francis Burnham, son of Norbert and Mary Short Burnham, was born in Chicago, Illinois, April 3, 1920. He rec8iVed his elementary schbol education at St. Ita's parochial schbol in Chicago and at the Scottville Public Schbol in Scott ville, Michigan. His first year high school was ~pent at the Scottville High School, and the latter three years at Nicholas Senn ITigh School in Chicago, from which he graduated in June, 1937 In September, 1937, he entered Wright Junior Colloge in Chicago and in June, 1939, finished his two year pre-legal course. -

Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain by Benjamin Zenas Cannon a Dissertation Submitted in Partia

Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Kent Puckett Professor Andrew Shanken Spring 2014 Disappearing Walls: Literature and Architecture in Victorian Britain © 2014 By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Abstract Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain By Benjamin Zenas Cannon Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Prof. Ian Duncan, Chair From Discipline and Punish and The Madwoman in the Attic to recent work on urbanism, display, and material culture, criticism has regularly cast nineteenth-century architecture not as a set of buildings but as an ideological metastructure. Seen primarily in terms of prisons, museums, and the newly gendered private home, this “grid of intelligibility” polices the boundaries not only of physical interaction but also of cultural values and modes of knowing. As my project argues, however, architecture in fact offered nineteenth-century theorists unique opportunities to broaden radically the parameters of aesthetic agency. A building is generally not built by a single person; it is almost always a corporate effort. At the same time, a building will often exist for long enough that it will decay or be repurposed. Long before literature asked “what is an author?” Victorian architecture theory asked: “who can be said to have made this?” Figures like John Ruskin, Owen Jones, and James Fergusson radicalize this question into what I call a redistribution of intention, an ethically charged recognition of the value of other makers. -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects.