Fiscal Decentralization in Practice: Jordan's Nascent Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

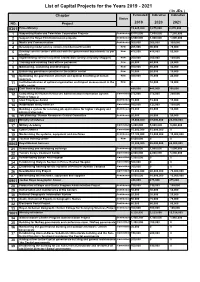

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-System of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (Sesos)

Entrepreneurship in Jordan: the Eco-system of the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) Amani Jarrar ( [email protected] ) Philadelphia University, Department of Development Studies Research Keywords: Entrepreneurship, Social Entrepreneurship, Eco-system, Jordan Posted Date: March 22nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-334076/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/50 Abstract This study aims at assessing the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs) in Jordan with an updated eco-system reecting the better resourced Social Entrepreneurship eco-system characterized with comprehensive information; covering the stakeholders’ identication data, ongoing projects and initiatives, work scope, and their targeted groups, accurate data based on a well-developed survey and analysis of the survey data by our experts. This study also aims at assessing the SESOs capacity by coincide their desired needs and their actual needs, and limit the social innovation concept variation among the different institutions in the ecosystem. This study provides a survey analysis for the Social Entrepreneurship Support Organizations (SESOs), and an attempt to identify their characteristics and roles in Jordan by adopting the qualitative and quantitative analysis approach as its methodology. Results show that (57.89%) of the SESO’s in Jordan have dedicated programs that focus on women's inclusion, and that (68.42%) are hiring more than 50% in their staff. Besides that, results also show that (59.65%) of the SESO’s in Jordan did not dedicate programs for people with disability (PWD); which is a high portion in neglecting this segment of people. -

Amman, Jordan

MINISTRY OF WATER AND IRRIGATION WATER YEAR BOOK “Our Water situation forms a strategic challenge that cannot be ignored.” His Majesty Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein “I assure you that the young people of my generation do not lack the will to take action. On the contrary, they are the most aware of the challenges facing their homelands.” His Royal Highness Hussein bin Abdullah Imprint Water Yearbook Hydrological year 2016-2017 Amman, June 2018 Publisher Ministry of Water and Irrigation Water Authority of Jordan P.O. Box 2412-5012 Laboratories & Quality Affairs Amman 1118 Jordan P.O. Box 2412 T: +962 6 5652265 / +962 6 5652267 Amman 11183 Jordan F: +962 6 5652287 T: +962 6 5864361/2 I: www.mwi.gov.jo F: +962 6 5825275 I: www.waj.gov.jo Photos © Water Authority of Jordan – Labs & Quality Affairs © Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Authors Thair Almomani, Safa’a Al Shraydeh, Hilda Shakhatreh, Razan Alroud, Ali Brezat, Adel Obayat, Ala’a Atyeh, Mohammad Almasri, Amani Alta’ani, Hiyam Sa’aydeh, Rania Shaaban, Refaat Bani Khalaf, Lama Saleh, Feda Massadeh, Samah Al-Salhi, Rebecca Bahls, Mohammed Alhyari, Mathias Toll, Klaus Holzner The Water Yearbook is available online through the web portal of the Ministry of Water and Irrigation. http://www.mwi.gov.jo Imprint This publication was developed within the German – Jordanian technical cooperation project “Groundwater Resources Management” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Implemented by: Foreword It is highly evident and well known that water resources in Jordan are very scarce. -

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly, and when the reproduction is for educational and non-commercial purposes, without a fee, subject to such attributions and notices as we may reasonably require. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The contents of this work are intended for general informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, securities, or investment advice, an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment, or a solicitation of any type. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties (including named herein. -

Jordan's National Dish

MIDDLE EAST Briefing Amman/Brussels, 8 October 2003 THE CHALLENGE OF POLITICAL REFORM: JORDANIAN DEMOCRATISATION AND REGIONAL INSTABILITY This briefing is one of a series of occasional ICG briefing papers and reports that will address the issue of political reform in the Middle East and North Africa. The absence of a credible political life in most parts of the region, while not necessarily bound to produce violent conflict, is intimately connected to a host of questions that affect its longer-term stability: Ineffective political representation, popular participation and government responsiveness often translate into inadequate mechanisms to express and channel public discontent, creating the potential for extra- institutional protests. These may, in turn, take on more violent forms, especially at a time when regional developments (in the Israeli-Palestinian theatre and in Iraq) have polarised and radicalised public opinion. In the long run, the lack of genuine public accountability and transparency hampers sound economic development. While transparency and accountability are by no means a guarantee against corruption, their absence virtually ensures it. Also, without public participation, governments are likely to be more receptive to demands for economic reform emanating from the international community than from their own citizens. As a result, policy-makers risk taking insufficient account of the social and political impact of their decisions. Weakened political legitimacy and economic under-development undermine the Arab states’ ability to play an effective part on the regional scene at a time of crisis when their constructive and creative leadership is more necessary than ever. The deficit of democratic representation may be a direct source of conflict, as in the case of Algeria. -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

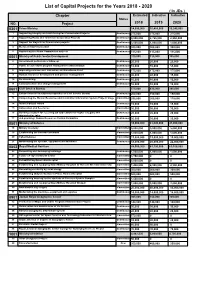

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2018 - 2020 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2018 2019 2020 0301 Prime Ministry 14,090,000 10,455,000 10,240,000 1 Supporting Integrity and Anti-Corruption Commission Projects Continuous 275,000 275,000 275,000 2 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 9,900,000 8,765,000 8,550,000 3 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 4 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 5 Supporting the Media Commission projects Continuous 115,000 115,000 115,000 0501 Ministry of Public Sector Development 310,000 310,000 305,000 6 Government performance follow up Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 7 Public sector reform program management administration Continuous 55,000 55,000 55,000 8 Improving services and Innovation and Excellence Fund Continuous 175,000 175,000 175,000 9 Human resources development and policies management Continuous 40,000 40,000 35,000 10 Re-structuring Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 11 Communication and change management Continuous 10,000 10,000 10,000 0601 Civil Service Bureau 575,000 435,000 345,000 12 Enhancement of institutional capacities of Civil Service Bureau Continuous 200,000 150,000 150,000 13 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Project/ Stage Committed 290,000 200,000 110,000 2 14 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 15 Automation and E-services Committed 30,000 30,000 30,000 16 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 20,000 20,000 20,000 administrative jobs. -

THE STARTUP GUIDE Business in Jordan

Your complete guide to registering and licensing a small THE STARTUP GUIDE business in Jordan Find out what to do, where to go and what fees are required to formalize your small business in this simple, step-by-step guide Contents WHY SHOULD I REGISTER AND LICENSE MY BUSINESS? ........................................................................................ 2 WHAT ARE THE STEPS I NEED TO TAKE IN ORDER TO FORMALIZE MY BUSINESS? ............................................... 3 HOW DO I KNOW WHAT TYPE OF BUSINESS TO REGISTER? ................................................................................. 4 HOW DO I CHOOSE A BUSINESS STRUCTURE THAT’S RIGHT FOR ME? ................................................................. 6 I’VE CHOSEN MY BUSINESS STRUCTURE… WHAT NEXT? ...................................................................................... 8 I’VE GOTTEN MY PRE-APPROVALS. HOW DO I REGISTER MY BUSINESS? ............................................................. 9 A) REGISTERING AN INDIVIDUAL ESTABLISHMENT ........................................................................................ 10 B) REGISTERING A GENERAL PARTNERSHIP OR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP COMPANY ...................................... 13 C) REGISTERING A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY ........................................................................................... 16 D) REGISTERING A PRIVATE SHAREHOLDING COMPANY................................................................................ 20 I’VE REGISTERED MY BUSINESS. HOW CAN I SET -

Role of Museums Within Jordanian Local Communities: Case Studies

Koji Oyama Koji Oyama Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) JICA Jordan Office PO Box 926355 Role of Museums Within Jordanian Local Amman 11190 Communities: Case Studies of the Karak Jordan Archaeological Museum, Historic Old Salt Museum and Dead Sea Museum Introduction Potential Role of Regional Museums within Since 1999, the Ministry of Tourism and Local Communities Antiquities (MOTA) in Jordan and the Japan Regional museums have a potentially International Cooperation Agency (JICA) have important social role within local communities. implemented the Tourism Sector Development With rich local collections, regional museums Project (TSDP)1. The geographical foci of this can be centers of education, study and local project include Amman, Karak, Salt and the heritage for local people. Potential roles for Dead Sea region. As part of the project, four regional museums include: museums, viz. the Jordan Museum (National Museum) in Amman, Karak Archaeological Museum, Historic Old Salt Museum and Dead Sea Museum (FIG. 1), were newly established or renovated. The JICA cooperation includes construction of these four museums, as well as preparation of the museum exhibitions, enhancement of the museum operation management systems and activities in the field of collection management, conservation and education. In this paper, of the four museums in which JICA has been involved, it is the three regional museums, viz. the Karak Archaeological Museum, Historic Old Salt Museum and Dead Sea Museum, which are discussed. The exhibition and community -

Consultative Process Report Consultative Meetings in the Kingdom Governorates

Consultative Process Report Consultative meetings in the Kingdom governorates Author MCA-Jordan team Millennium Challenge Account - Jordan P.O. Box 80 Amman 11180 Jordan March 2009 Prime Ministry Table Of Contents Executive Summary 3 1. General Background 10 1.1 Introduction 10 1.2 Millennium Challenge Unit - Jordan 11 1.3 Millennium Challenge Corporation 14 2. Consultative Process 16 2.1 Consultative Meetings in the Kingdom Governorates 18 2.2 Methodology 21 3. The Consultative Meetings Results in the Kingdom Governorates 30 3.1 Balqa Governorate 30 3.2 Irbid Governorate 35 3.3 Ajlun Governorate 41 3.4 Zarqa Governorate 46 3.5 Mafraq Governorate 52 3.6 Karak Governorate 57 3.7 Madaba Governorate 62 3.8 Tafileh Governorate 67 3.9 Ma’an Governorate 74 3.10 Aqaba Governorate 80 3.11 Jerash Governorate 85 3.12 The Capital Governorate 89 Appendices 96 A.1 Millennium Challenge Account (MCA – Jordan) Team 97 A.2 Jordan River Foundation Team 97 A.3 Participants in Consultative Meetings 98 A.4 Consultative Meetings Agenda 120 A.5 List of the Materials Distributed During the Meeting 121 A.6 Power point presentation on the Millennium Challenge Account- 121 Jordan Millennium Challenge Account-Joradn/ Consultative Process report 2 24/4/2008-26/5/2008 Prime Ministry Executive Summary Introduction Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) is an institution under the U.S. government which was established in 2004 to work with some of the low-income countries in the world. MCC relies on the principle that aid becomes more effective when it promotes good governance, economic liberalization and investment in people who seek to achieve economic growth and eradicate the extreme cases of poverty. -

Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2009

Jordan 2009 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey Population and Family Health Survey 2009 THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2009 Department of Statistics Amman, Jordan ICF Macro Calverton, Maryland, USA May 2010 CONTRIBUTORS DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS Dr. Haidar Fraihat Fathi Nsour Ikhlas Aranki Kamal Saleh Wajdi Akeel Zeinab Dabbagh Ahmad Hiyari MINISTRY OF HEALTH Dr. Adel Belbeisi Dr. Bassam Hijawi UNIVERSITY OF JORDAN Dr. Issa Masarweh ICF MACRO Bernard Barrère Lyndsey Wilson-Williams Mohamed Ayad Nourredine Abderrahim This report summarizes the findings of the 2009 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS) carried out by the Department of Statistics (DoS). The survey was funded by the government of Jordan. Additional funding was provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). ICF Macro provided technical assistance through the MEASURE DHS program. The JPFHS is part of the worldwide Demographic and Health Surveys Program, which is designed to collect data on fertility, family planning, and maternal and child health. Additional information about the Jordan survey may be obtained from the Department of Statistics, P.O. Box 2015, Amman 11181, Jordan (Telephone (962) 6-5-300-700; Fax (962) 6-5- 300-710; e-mail [email protected]). Additional information about the MEASURE DHS program may be obtained from ICF Macro, 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300, Calverton, MD 20705 (Telephone 301-572-0200; Fax 301-572-0999; e-mail [email protected]). Suggested citation: Department of Statistics [Jordan] and ICF Macro. 2010. Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2009. -

Development of the Road Network in the City of Salt in 2004 and 2016 Using GIS

Modern Applied Science; Vol. 13, No. 10; 2019 ISSN 1913-1844 E-ISSN 1913-1852 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Development of the Road Network in the City of Salt in 2004 and 2016 Using GIS Dr. Deaa Al-Deen Amjad Qtaishat1, Dr. Abd Al Azez Hdoush2 & Eng. Loiy Qasim Alzu’Bi3 1Faculty member at the Arab University College of Technology, Amman, Jordan 2 Lecturer, Jordan University, Jordan 3 Lecturer, Jerash University, Jordan Correspondence: Dr. Deaa Al-Deen Amjad Qtaishat, Faculty member at the Arab University College of Technology, Amman, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 20, 2019 Accepted: September 18, 2019 Online Published: September 19, 2019 doi:10.5539/mas.v13n10p94 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v13n10p94 Abstract The aim of this study is to analyze the structure of the road network in As-Salt City in the period between 2004 and 2016, in order to identify the road employability in terms of the degree of connectivity, rotation, accessibility, and density. The relationship between the social properties and road distribution are also examined through analysis of the network characteristics concerning population distribution. The data used in this study was based on the As-Salt City Municipality Database supported with fieldwork done in 2016. The network analysis approach using GIS was used to calculate the roads employability. The study compares between the results of the analysis using the cognitive model of the road network for the years 2004 and 2016, knowing that the number of nodes in 2004 and 2016 was constant indicating the number of neighborhoods is 20, while the number of links changed from 42 links in 2004 to 50 links in 2016 and the average center of roads was determined, and it was estimated that the average road center is located near the municipality of As-Salt The study indicates that the road network suffers from a low degree of communication and rotation and the standard distance of road sites in the study area.