Das Rheingold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner's Opera Cycle

Inside the Ring: Essays on Wagner’s Opera Cycle John Louis DiGaetani Professor Department of English and Freshman Composition James Morris as Wotan in Wagner’s Die Walküre. Photo: Jennifer Carle/The Metropolitan Opera hirty years ago I edited a book in the 1970s, the problem was finding a admirer of Hitler and she turned the titled Penetrating Wagner’s Ring: performance of the Ring, but now the summer festival into a Nazi showplace An Anthology. Today, I find problem is finding a ticket. Often these in the 1930s and until 1944 when the myself editing a book titled Ring cycles — the four operas done festival was closed. But her sons, Inside the Ring: Essays on within a week, as Wagner wanted — are Wieland and Wolfgang, managed to T Wagner’s Opera Cycle — to be sold out a year in advance of the begin- reopen the festival in 1951; there, published by McFarland Press in spring ning of the performances, so there is Wieland and Wolfgang’s revolutionary 2006. Is the Ring still an appropriate clearly an increasing demand for tickets new approaches to staging the Ring and subject for today’s audiences? Absolutely. as more and more people become fasci- the other Wagner operas helped to In fact, more than ever. The four operas nated by the Ring cycle. revive audience interest and see that comprise the Ring cycle — Das Wagnerian opera in a new visual style Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Political Complications and without its previous political associ- Götterdämmerung — have become more ations. Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner and more popular since the 1970s. -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Spring 2008-Final

Wagneriana Endloser Grimm! Ewiger Gram! Spring 2008 Der Traurigste bin ich von Allen! Volume 5, Number 2 —Die Walküre From the Editor ven though the much-awaited concert of the Wagner/Liszt piano transcriptions was canceled due to un- avoidable circumstances (the musicians were unable to obtain a visa), the winter and early spring months E brought several stimulating events. On January 19, Vice President Erika Reitshamer gave an audiovisual presentation on Wagner’s early opera Das Liebesverbot. This well-attended event was augmented by photocopies of extended excerpts from the libretto, with frequently amusing commentary by the presenter on Wagner’s influences and foreshadowings of his future operas. February 23 brought the excellent talk by Professor Hans Rudolf Vaget of Smith College. Professor Vaget spoke about Wagner’s English biographer Ernest Newman, whose seminal four-volume book The Life of Richard Wagner has never been surpassed in its thoroughness. In the early part of the twentieth century, the music critic Newman served as a counterbalance to his fellow countryman Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Wagner’s son-in-law and an ardent Nazi. The talk also included aspects of Thomas Mann’s fictional writings on Wagner, as well as the philoso- pher and musician Theodor Adorno and Wagner’s other son-in-law Franz Beidler. On April 19 we learned the extent of Buddhism’s influence on Wagner’s operas thanks to a lecture and book signing by Paul Schofield, author of The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring. The audience members were so interested in what Mr. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

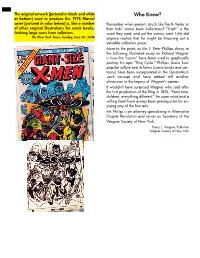

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

Ebook Download Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around

WAGNERS RING TURNING THE SKY AROUND - AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Owen Lee | 9780879101862 | | | | | Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around - An Introduction to the Ring of the Nibelung 1st edition PDF Book It is even possible for the orchestra to convey ideas that are hidden from the characters themselves—an idea that later found its way into film scores. Unfamiliarity with Wagner constitutes an ignorance of, well, Wagnerian proportions. Some of my friends have seen far more than these. This section does not cite any sources. Digital watches chime the hour in half-diminished seventh chords. The daughters of the Rhine come up and pull Hagen into the depth of the Rhine. The plot synopses were helpful, but some of the deep psychological analysis was a bit boring. Next he encounters Wotan his grandfather , quarrels with him and cuts Wotan's staff of power in half. The next possessor of the ring, the giant Fafner, consumed with greed and lust for power, kills his brother, Fasolt, taking the spoils to the deep forest while the gods enter Valhalla to some of the most glorious and ironically triumphant music imaginable. Has underlining on pages. John shares his recipe for Nectar of the Gods. April Learn how and when to remove this template message. It's actually OK because that's what Wotan decreed for her anyway: First one up there shall have you. See Article History. Politics and music often go together. It left me at a whole new level of self-awareness, and has for all the years that have followed given me pleasures and insights that have enriched my life. -

Notes on Wagner's Ring Cycle

THE RING CYCLE BACKGROUND FOR NC OPERA By Margie Satinsky President, Triangle Wagner Society April 9, 2019 Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle includes four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walkure, Siegfried, and Gotterdammerung. What’s so special about the Ring Cycle? Here’s what William Berger, author of Wagner without Fear, says: …the Ring is probably the longest chunk of music and/or drama ever put before an audience. It is certainly one of the best. There is nothing remotely like it. The Ring is a German Romantic view of Norse and Teutonic myth influenced by both Greek tragedy and a Buddhist sense of destiny told with a sociopolitical deconstruction of contemporary society, a psychological study of motivation and action, and a blueprint for a new approach to music and theater.” One of the most fascinating characteristics of the Ring is the number of meanings attributed to it. It has been seen as a justification for governments and a condemnation of them. It speaks to traditionalists and forward-thinkers. It is distinctly German and profoundly pan-national. It provides a lifetime of study for musicologists and thrilling entertainment. It is an adventure for all who approach it. SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE RING CYCLE Wagner was extremely critical of the music of his day. Unlike other composers, he not only wrote the music and the libretto, but also dictated the details of each production. The German word for total work of art, Gesamtkunstwerk, means the synthesis of the poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts with music subsidiary to drama. As a composer, Wagner was very interested in themes, and he uses them in The Ring Cycle in different ways. -

Old Norse Mythology and the Ring of the Nibelung

Declaration in lieu of oath: I, Erik Schjeide born on: July 27, 1954 in: Santa Monica, California declare, that I produced this Master Thesis by myself and did not use any sources and resources other than the ones stated and that I did not have any other illegal help, that this Master Thesis has not been presented for examination at any other national or international institution in any shape or form, and that, if this Master Thesis has anything to do with my current employer, I have informed them and asked their permission. Arcata, California, June 15, 2008, Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung Master Thesis zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades “Master of Fine Arts (MFA) New Media” Universitätslehrgang “Master of Fine Arts in New Media” eingereicht am Department für Interaktive Medien und Bildungstechnologien Donau-Universität Krems von Erik Schjeide Krems, July 2008 Betreuer/Betreuerin: Carolyn Guertin Table of Contents I. Abstract 1 II. Introduction 3 III. Wagner’s sources 7 IV. Wagner’s background and The Ring 17 V. Das Rheingold: Mythological beginnings 25 VI. Die Walküre: Odin’s intervention in worldly affairs 34 VII. Siegfried: The hero’s journey 43 VIII. Götterdämmerung: Twilight of the gods 53 IX. Conclusion 65 X. Sources 67 Appendix I: The Psychic Life Cycle as described by Edward Edinger 68 Appendix II: Noteworthy Old Norse mythical deities 69 Appendix III: Noteworthy names in The Volsung Saga 70 Appendix IV: Summary of The Thidrek Saga 72 Old Norse Mythology and The Ring of the Nibelung I. Abstract As an MFA student in New Media, I am creating stop-motion animated short films. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera.