The Function of the Pellichus Sequence at Lucian Philopseudes 18-20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Morals, Vol. 2 [1878]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6509/the-morals-vol-2-1878-146509.webp)

The Morals, Vol. 2 [1878]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Plutarch, The Morals, vol. 2 [1878] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. LIBERTY FUND, INC. -

A History of Cynicism

A HISTORY OF CYNICISM Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com A HISTORY OF CYNICISM From Diogenes to the 6th Century A.D. by DONALD R. DUDLEY F,llow of St. John's College, Cambrid1e Htmy Fellow at Yale University firl mll METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street, Strand, W.C.2 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com First published in 1937 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com PREFACE THE research of which this book is the outcome was mainly carried out at St. John's College, Cambridge, Yale University, and Edinburgh University. In the help so generously given to my work I have been no less fortunate than in the scenes in which it was pursued. I am much indebted for criticism and advice to Professor M. Rostovtseff and Professor E. R. Goodonough of Yale, to Professor A. E. Taylor of Edinburgh, to Professor F. M. Cornford of Cambridge, to Professor J. L. Stocks of Liverpool, and to Dr. W. H. Semple of Reading. I should also like to thank the electors of the Henry Fund for enabling me to visit the United States, and the College Council of St. John's for electing me to a Research Fellowship. Finally, to• the unfailing interest, advice and encouragement of Mr. M. P. Charlesworth of St. John's I owe an especial debt which I can hardly hope to repay. These acknowledgements do not exhaust the list of my obligations ; but I hope that other kindnesses have been acknowledged either in the text or privately. -

12Th Grade Senior English IV and Dual Enrollment 2021 Summer

Summer Reading List: Senior English and Dual Enrollment Pride and Prejudice 1. Read and annotate this novel. Take note of literary elements, characterization, plot, setting, tone, and vocabulary. 2. Choose one of the following options below. The piece must be 500 words (about two pages, typed, double-spaced, 12-point Times New Roman) Due date: This assignment will be submitted electronically via TEAMS as well as TurnItIn.com during the first week of school. Be sure the assignment is completed when you arrive the first day of classes so that you are able to submit it as soon as TEAMS and TurnItIn.com are launched. a. Quote, cite, and analyze three passages from the novel that represent or discuss gender, social norms, or class and status-based ideas addressed in the novel. b. Write an original letter from any character to another character that reveals his or her personality, fears, desires, prejudices, and/or ways of dealing with conflict. c. Write a skit or scene based on your own rendition of the customs and values of the time and place in which the novel takes place. This would be an added scene in the story. Make sure you inform me where this scene would take place if it were actually in the novel. d. Write an original poem (30-line minimum) about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennet family or the society in which people live. Examples: the soldiers, fate, religion, upper class, etc. Mythology by Edith Hamilton 1. Read the novel. You do not have to annotate. -

The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley

The Rôle of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr.1 Stanley, Keith Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1976; 17, 4; ProQuest pg. 305 The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley APPHO'S Hymn to Aphrodite, standing so near to the beginning of Sour evidence for the religious and poetic traditions it embodies, remains a locus of disagreement about the function of the goddess in the poem and the degree of seriousness intended by Sappho's plea for her help. Wilamowitz thought sparrows' wings unsuited to the task of drawing Aphrodite's chariot, and proposed that Sappho's report of her epiphany described a vision experienced ovap, not v7rap.l Archibald Cameron ventured further, suggesting that the description of Aphrodite's flight was couched not in the language of "the real religious tradition of epiphany and its effect on mortals" but was "Homeric and conventional"; and that the vision was not, therefore, the record of a genuine religious experience, but derived rather from "the bright world of Homer's fancy."2 Thus he judged the tone of the ode to be one of seriousness tempered by "a vein of prettiness and almost of playfulness" and concluded that there was no special ur gency in Sappho's petition itself. While more recent opinion has tended to regard the episode as a poetic fiction which serves to 'mythologize' a genuine emotion, Sir Denys Page has not only maintained that Aphrodite's descent is a "flight of fancy, with much detail irrelevant to her present theme," but argued further that the poem as a whole is a lightly ironic melange of passion and self-mockery.3 Despite a con- 1 Sappho und Simonides (Berlin 1913) 45, with Der Glaube der Hellenen 3 II (Basel 1959) 109; so also J. -

The Medici Aphrodite Angel D

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite Angel D. Arvello Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Arvello, Angel D., "A Hellenistic masterpiece: the Medici Aphrodite" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2015. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A HELLENISTIC MASTERPIECE: THE MEDICI APRHODITE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Angel D. Arvello B. A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 1996 May 2005 In Memory of Marcel “Butch” Romagosa, Jr. (10 December 1948 - 31 August 1998) ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to acknowledge the support of my parents, Paul and Daisy Arvello, the love and support of my husband, Kevin Hunter, and the guidance and inspiration of Professor Patricia Lawrence in addition to access to numerous photographs of hers and her coin collection. I would also like to thank Doug Smith both for his extensive website which was invaluable in writing chapter four and for his permission to reproduce the coin in his private collection. -

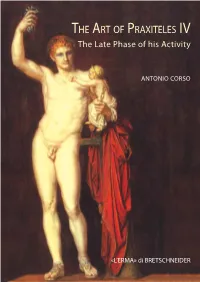

SEAT of the WORLD of Beautiful and Gentle Tales Are Discovered and Followed Through Their Development

The book is focused on the late production of the 4th c. BC Athenian sculptor Praxiteles and in particular 190 on his oeuvre from around 355 to around 340 BC. HE RT OF RAXITELES The most important works of this master considered in this essay are his sculptures for the Mausoleum of T A P IV Halicarnassus, the Apollo Sauroctonus, the Eros of Parium, the Artemis Brauronia, Peitho and Paregoros, his Aphrodite from Corinth, the group of Apollo and Poseidon, the Apollinean triad of Mantinea, the The Late Phase of his Activity Dionysus of Elis, the Hermes of Olympia and the Aphrodite Pseliumene. Complete lists of ancient copies and variations derived from the masterpieces studied here are also provided. The creation by the artist of an art of pleasure and his visual definition of a remote and mythical Arcadia SEAT OF THE WORLD of beautiful and gentle tales are discovered and followed through their development. ANTONIO CORSO Antonio Corso attended his curriculum of studies in classics and archaeology in Padua, Athens, Frank- The Palatine of Ancient Rome furt and London. He published more than 100 scientific essays (articles and books) in well refereed peri- ate Phase of his Activity Phase ate odicals and series of books. The most important areas covered by his studies are the ancient art criticism L and the knowledge of classical Greek artists. In particular he collected in three books all the written tes- The The timonia on Praxiteles and in other three books he reconstructed the career of this sculptor from around 375 to around 355 BC. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48147-2 — Scale, Space and Canon in Ancient Literary Culture Reviel Netz Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48147-2 — Scale, Space and Canon in Ancient Literary Culture Reviel Netz Index More Information Index Aaker, Jennifer, 110, 111 competition, 173 Abdera, 242, 310, 314, 315, 317 longevity, 179 Abel, N. H., 185 Oresteia, 197, 200, 201 Academos, 189, 323, 324, 325, 337 papyri, 15 Academy, 322, 325, 326, 329, 337, 343, 385, 391, Persians, 183 399, 404, 427, 434, 448, 476, 477–8, 512 portraits, 64 Achilles Tatius, 53, 116, 137, 551 Ptolemaic era, 39 papyri, 16, 23 Aeschylus (astronomer), 249 Acta Alexandrinorum, 87, 604 Aesop, 52, 68, 100, 116, 165 adespota, 55, 79, 81–5, 86, 88, 91, 99, 125, 192, 194, in education, 42 196, 206, 411, 413, 542, 574 papyri, 16, 23 Adkin, Neil, 782 Aethiopia, 354 Adrastus, 483 Aetia, 277 Adrastus (mathematician), 249 Africa, 266 Adrianople, 798 Agatharchides, 471 Aedesius (martyr), 734, 736 Agathocles (historian), 243 Aegae, 479, 520 Agathocles (peripatetic), 483 Aegean, 338–43 Agathon, 280 Aegina, 265 Agias (historian), 373 Aelianus (Platonist), 484 agrimensores, 675 Aelius Aristides, 133, 657, 709 Ai Khanoum, 411 papyri, 16 Akhmatova, Anna, 186 Aelius Herodian (grammarian), 713 Albertus Magnus, 407 Aelius Promotus, 583 Albinus, 484 Aenesidemus, 478–9, 519, 520 Alcaeus, 49, 59, 61–2, 70, 116, 150, 162, 214, 246, Aeolia, 479 see also Aeolian Aeolian, 246 papyri, 15, 23 Aeschines, 39, 59, 60, 64, 93, 94, 123, 161, 166, 174, portraits, 65, 67 184, 211, 213, 216, 230, 232, 331 Alcidamas, 549 commentaries, 75 papyri, 16 Ctesiphon, 21 Alcinous, 484 False Legation, 22 Alcmaeon, 310 -

Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron's Letters

The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters Michel Briand To cite this version: Michel Briand. The Girlfriends’ Letters : Poikilia in the Book 4 of Alciphron’s Letters. The Letters of Alciphron : To Be or not To be a Work ?, Jun 2016, Nice, France. hal-02522826 HAL Id: hal-02522826 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02522826 Submitted on 27 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THE GIRLFRIENDS’ LETTERS: POIKILIA IN THE BOOK 4 OF ALCIPHRON’S LETTERS Michel Briand Alciphron, an ambivalent post-modern Like Lucian of Samosata and other sophistic authors, as Longus or Achilles Tatius, Alciphron typically represents an ostensibly post-classical brand of literature and culture, which in many ways resembles our post- modernity, caught in permanent tension between virtuoso, ironic, critical, and distanced meta-fictionality, on the one hand, and a conscious taste for outspoken and humorous “bad taste”, Bakhtinian carnavalesque, social and moral margins, convoluted plots and sensational plays of immersion and derision, or realism and artificiality: the way Alciphron’s collection has been judged is related to the devaluation, then revaluation, the Second Sophistic was submitted to, according to inherently aesthetical and political arguments, quite similar to those with which one often criticises or defends literary, theatrical, or cinematographic post- 1 modernity. -

Marsyas in the Garden?

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Habetzeder, J. (2010) Marsyas in the garden?: Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Opuscula: Annual of the Swedish Institutes at Athens and Rome, 3: 163-178 https://doi.org/10.30549/opathrom-03-07 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-274654 MARSYAS IN THE GARDEN? • JULIA HABETZEDER • 163 JULIA HABETZEDER Marsyas in the garden? Small-scale sculptures referring to the Marsyas in the forum Abstract antiquities bought in Rome in the eighteenth century by While studying a small-scale sculpture in the collections of the the Swedish king Gustav III. This collection belongs today Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, I noticed that it belongs to a pre- to the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. It is currently being viously unrecognized sculpture type. The type depicts a paunchy, thoroughly published and a number of articles on the col- bearded satyr who stands with one arm raised. To my knowledge, four lection have previously appeared in Opuscula Romana and replicas exist. By means of stylistic comparison, they can be dated to 3 the late second to early third centuries AD. Due to their scale and ren- Opuscula. dering they are likely to have been freestanding decorative elements in A second reason why the sculpture type has not previ- Roman villas or gardens. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01205-9 — Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World Nathanael J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01205-9 — Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World Nathanael J. Andrade Index More Information Index Maccabees, , , , Armenian tiara and Persian dress, Maccabees, , , , , as Roman citizen, Commagene as hearth, Abgar X (c. –), , , compared with Herod I, Abgarid dynasty of Edessa, culture and cult sustained by gods, Abidsautas, Aurelios (Beth Phouraia), , dexiosis, , , Galatians, , Achaemenid Persians, , , , , , , , Greek and Persian divinities, , , , , Greek, Persian, and Armenian ancestry, , Acts of the Apostles, Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), , , hierothesion at Nemrud Dag,˘ , , Agrippa, Marcus Vipsanius, , hybridity, , , Akkadian cuneiform, , , , , , , Nemrud DagasDelphi,˘ Alexander III of Macedon (the Great) (– organizes regional community, , , bce), , , , , , , , , , priests in Persian clothing, , , , , , , sacred writing of, Alexander of Aboniteichos (false prophet), , statues of himself, ancesters, and gods, successors patronize poleis, Alexander, Markos Aurelios of Markopolis, trends of his reign, , Anath/Anathenes, , , , , , , Tych¯e, , Antiochus I, Seleucid (– bce), , , Antioch among the Jerusalemites (Jerusalem), Antiochus II, Seleucid (– bce), , , , , , , , , , Antiochus III, Seleucid (– bce), , , Antioch at Daphne, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , Antiochus IV of Commagene (– ce), , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , Antiochus IV, Seleucid (– bce), , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , bilingual/multilingual Alexander, , , , , , , , , -

View / Download 2.4 Mb

Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by David William Frierson Stifler 2019 Abstract This dissertation investigates ancient language ideologies constructed by Greek and Latin writers of the second and third centuries CE, a loosely-connected movement now generally referred to the Second Sophistic. It focuses on Lucian of Samosata, a Syrian “barbarian” writer of satire and parody in Greek, and especially on his works that engage with language-oriented topics of contemporary relevance to his era. The term “language ideologies”, as it is used in studies of sociolinguistics, refers to beliefs and practices about language as they function within the social context of a particular culture or set of cultures; prescriptive grammar, for example, is a broad and rather common example. The surge in Greek (and some Latin) literary output in the Second Sophistic led many writers, with Lucian an especially noteworthy example, to express a variety of ideologies regarding the form and use of language. -

The Ptolemaic Sea Empire

chapter 5 The Ptolemaic Sea Empire Rolf Strootman Introduction: Empire or “Overseas Possessions”? In 1982, archaeologists of the State Hermitage Museum excavated a sanctu- ary at the site of Nymphaion on the eastern shore of the Crimea. The sanctu- ary had been in use from ca. 325 bce until its sudden abandonment around 250 bce.1 An inscription found in situ associates the site with Aphrodite and Apollo, and with a powerful local dynasty, the Spartokids.2 Built upon a rocky promontory overlooking the Kimmerian Bosporos near the port of Panti- kapaion (the seat of the Spartokids), the sanctuary clearly was linked to the sea. Most remarkable among the remains were two polychrome plastered walls covered with graffiti depicting more than 80 ships—both war galleys and cargo vessels under sail— of varying size and quality, as well as images of animals and people. The most likely interpretation of the ship images is that they were connected to votive offerings made to Aphrodite (or Apollo) in return for safe voyages.3 Most noticeable among the graffiti is a detailed, ca. 1.15 m. wide drawing of a warship, dated by the excavators to ca. 275–250, and inscribed on its prow with the name “Isis” (ΙΣΙΣ).4 The ship is commonly 1 All dates hereafter will be Before Common Era. I am grateful to Christelle Fischer-Bovet’s for her generous and critical comments. 2 SEG xxxviii 752; xxxix 701; the inscription mentions Pairisades ii, King of the Bosporos (r. 284/3– 245), and his brother. Kimmerian Bosporos is the ancient Greek name for the Chan- nel now known as the Strait of Kerch, and by extension the entire Crimea/ Sea of Azov region; see Wallace 2012 with basic bibliography.