Chapter 7.1 Notes I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru

Tearing Down Old Walls in the New World: Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru Megan Proffitt The country of Peru is an interesting area, bordered by mountains on one side and the ocean on the other. This unique environment was home to numerous pre-Columbian cultures, several of which are well- known for their creativity and technological advancements. These cul- tures include such groups as the Chavin, Nasca, Inca, and Moche. The last of these, the Moche, flourished from about 0-800 AD and more or less dominated Peru’s northern coast. During the 2001 summer archaeological field season, I was granted the opportunity to travel to Peru and participate in the excavation of the Huaca de Huancaco, a Moche palace. In recent years, as Dr. Steve Bourget and his colleagues have conducted extensive research and fieldwork on the site, the cul- tural identity of its inhabitants have come into question. Although Huancaco has long been deemed a Moche site, Bourget claims that it is not. In this paper I will give a general, widely accepted description of the Moche culture and a brief history of the archaeological work that has been conducted on it. I will then discuss the site of Huancaco itself and my personal involvement with it. Finally, I will give a brief account of the data that have, and have not, been found there. This information is crucial for the necessary comparisons to other Moche sites required by Bourget’s claim that Huancaco is not a Moche site, a claim that will be explained and supported in this paper. -

The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us About Northern Textile Production?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Universidad Complutense de Madrid Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Jiménez Díaz, María Jesús, "The Evolution and Changes of Moche Textile Style: What Does Style Tell Us about Northern Textile Production?" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 403. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/403 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE EVOLUTION AND CHANGES OF MOCHE TEXTILE STYLE: WHAT DOES STYLE TELL US ABOUT NORTHERN TEXTILE PRODUCTION? María Jesús Jiménez Díaz Museo de América de Madrid / Universidad Complutense de Madrid Although Moche textiles form part of the legacy of one of the best known cultures of pre-Hispanic Peru, today they remain relatively unknown1. Moche culture evolved in the northern valleys of the Peruvian coast (Fig. 1) during the first 800 years after Christ (Fig. 2). They were contemporary with other cultures such us Nazca or Lima and their textiles exhibited special features that are reflected in their textile production. Previous studies of Moche textiles have been carried out by authors such as Lila O'Neale (1946, 1947), O'Neale y Kroeber (1930), William Conklin (1978) or Heiko Pruemers (1995). -

The Moche Lima Beans Recording System, Revisited

THE MOCHE LIMA BEANS RECORDING SYSTEM, REVISITED Tomi S. Melka Abstract: One matter that has raised sufficient uncertainties among scholars in the study of the Old Moche culture is a system that comprises patterned Lima beans. The marked beans, plus various associated effigies, appear painted by and large with a mixture of realism and symbolism on the surface of ceramic bottles and jugs, with many of them showing an unparalleled artistry in the great area of the South American subcontinent. A range of accounts has been offered as to what the real meaning of these items is: starting from a recrea- tional and/or a gambling game, to a divination scheme, to amulets, to an appli- cation for determining the length and order of funerary rites, to a device close to an accountancy and data storage medium, ending up with an ‘ideographic’, or even a ‘pre-alphabetic’ system. The investigation brings together structural, iconographic and cultural as- pects, and indicates that we might be dealing with an original form of mnemo- technology, contrived to solve the problems of medium and long-distance com- munication among the once thriving Moche principalities. Likewise, by review- ing the literature, by searching for new material, and exploring the structure and combinatory properties of the marked Lima beans, as well as by placing emphasis on joint scholarly efforts, may enhance the studies. Key words: ceramic vessels, communicative system, data storage and trans- mission, fine-line drawings, iconography, ‘messengers’, painted/incised Lima beans, patterns, pre-Inca Moche culture, ‘ritual runners’, tokens “Como resultado de la falta de testimonios claros, todas las explicaciones sobre este asunto parecen in- útiles; divierten a la curiosidad sin satisfacer a la razón.” [Due to a lack of clear evidence, all explana- tions on this issue would seem useless; they enter- tain the curiosity without satisfying the reason] von Hagen (1966: 157). -

Moche Culture As Political Ideology

1 HE STRUCTURALPARADOX: MOCHECULTURE AS POLITICALIDEOLOGY GarthBawden In this article I demonstrate the utility of an historical study of social change by examining the development of political authority on the Peruvian north coast during the Moche period through its symbols of power. Wetoo often equate the mater- ial record with "archaeological culture,^^assume that it reflects broad cultural realityXand interpret it by reference to gener- al evolutionary models. Here I reassess Moche society within its historic context by examining the relationship between underlying social structure and short-termprocesses that shaped Moche political formation, and reach very different con- clusions. I see the "diagnostic" Moche material recordprimarily as the symbolic manifestationof a distinctivepolitical ide- ology whose character was historically constituted in an ongoing cultural tradition.Aspiring rulers used ideology to manip- ulate culturalprinciples in their interests and thus mediate the paradox between exclusive power and holistic Andean social structure which created the dynamicfor change. A historic study allows us to identify the symbolic and ritual mechanisms that socially constituted Moche ideologyXand reveals a pattern of diversity in time and space that was the product of differ- ential choice by local rulers, a pattern that cannot be seen within a theoretical approach that emphasizes general evolution- ary or materialistfactors. En este articulo demuestro la ventaja de un estudio historico sobre la integraciony el cambio social, a traves de un examen del caracter del poder politico en la costa norte del Peru durante el periodo Moche. Con demasiadafrecuencia equiparamos el registro material con "las culturas arqueologicas "; asumimos que este refleja la realidad cultural amplia y la interpreta- mos con referencia a modelos evolutivos generales. -

EXPRESSIONS and SEVERITY of DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASES: a COMPARATIVE STUDY of JOINT PATHOLOGY in the LAMBAYEQUE REGION, NORTH COAST PERU By

EXPRESSIONS AND SEVERITY OF DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF JOINT PATHOLOGY IN THE LAMBAYEQUE REGION, NORTH COAST PERU by Michelle L. Yockey A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Anthropology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA “Expressions and Severity of Degenerative Joint Diseases: A Comparative Study of Joint Pathology in the Lambayeque Region, North Coast Peru” A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University By Michelle L. Yockey Bachelor of Arts Ball State University, 2016 Director: Haagen D. Klaus Department of Sociology and Anthropology Spring Semester 2019 George Mason University Fairfax, VA DEDICATION This work is dedicated to extremely supporting and loving partner, Anthony. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everyone who had a part in supporting me through this process. My supporting partner, Anthony, helped me immensely by talking though ideas with me and helping me through the writer’s block. My parents, Douglas and Nancy, for loving and pushing me to get this far. My colleague, Liz, for being a great friend and listener throughout the drafting of this thesis. Dr. Haagen Klaus, for helping me throughout every process of this paper and mentoring me through this process. I’d also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Daniel Temple and Dr. Cortney Hughes Rinker. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page Dedication .......................................................................................................................... -

Peoples and Civilizations of the Americas

PeoplesPeoples and and Civilizations Civilizations of of thethe Americas Americas 600600--15001500 TeotihuacanTeotihuacan TeotihuacanTeotihuacan waswas aa largelarge MesoamericanMesoamerican citycity atat thethe heightheight ofof itsits powerpower inin 450450––600600 c.ec.e.. TheThe citycity hadhad aa populationpopulation ofof 125,000125,000 toto 200,000200,000 inhabitantsinhabitants DominatedDominated byby religiousreligious structuresstructures PyramidsPyramids andand templestemples wherewhere humanhuman sacrificesacrifice waswas carriedcarried out.out. TheThe growth growth of of Teotihuacan Teotihuacan MadeMade possiblepossible byby forcedforced relocationrelocation ofof farmfarm familiesfamilies toto thethe citycity ByBy agriculturalagricultural innovationsinnovations includingincluding irrigationirrigation worksworks andand chinampaschinampas ((““floatingfloating gardensgardens””)) thatthat ThisThis increasedincreased foodfood productionproduction andand thusthus supportedsupported aa largerlarger populationpopulation ChinampasChinampas ApartmentApartment--likelike stonestone buildingsbuildings housedhoused commoners,commoners, includingincluding thethe artisansartisans whowho mademade potterypottery andand obsidianobsidian toolstools andand weaponsweapons forfor exportexport TheThe elite:elite: LivedLived inin separateseparate residentialresidential compoundscompounds ControlledControlled thethe statestate bureaucracy,bureaucracy, taxtax collection,collection, andand commerce.commerce. WhoWho controlled controlled Teotihuacan Teotihuacan -

Chapter Summary

0033-wh10a-CIB-02 11/13/2003 12:07 PM Page 33 Name Date CHAPTER CHAPTERS IN BRIEF The Americas: A Separate World, 9 40,000 B.C.–A.D. 700 Summary CHAPTER OVERVIEW Long ago, huge ice sheets cover the land. The level of the oceans goes down, and a once-underwater bridge of land connects Asia and the Americas. Asian hunters cross this bridge and become the first Americans. They spread down the two continents. They develop more complex societies and new civilizations. The earliest of these new cultures are found in central Mexico and in the high Andes Mountains. 1 The Earliest Americans with thick, long hair to protect it from the bitter KEY IDEA The first Americans were separated from cold of the Ice Age. It was so large that one animal other parts of the world. Nevertheless, they developed in alone gave enough meat, hide, and bones to feed, similar ways. clothe, and house many people. orth and South America form a single stretch Over time, all the mammoths died, and the peo- Nof land that reaches from the freezing cold ple were forced to look for other food. They began of the Arctic Circle in the north to the icy waters to hunt smaller animals such as rabbits and deer around Antarctica in the south. Two oceans on and to fish. They also began to gather plants and either side of these land masses separate them fruits to eat. Because they no longer had to roam from Africa, Asia, and Europe. over large areas to search for the mastodon, they That was not always the case, though. -

Ancash, Peru), Ad 400–800

Fortifications as Warfare Culture Fortifications as Warfare Culture: the Hilltop Centre of Yayno (Ancash, Peru), ad 400–800 George F. Lau This article evaluates defensive works at the ancient hilltop centre of Yayno, Pomabamba, north highlands, Peru. Survey, mapping and sampling excavations show that its primary occupation dates to cal. ad 400–800, by groups of the Recuay tradition. At the centre of a network articulating small nearby farming villages, Yayno features an impressive series of natural and built defensive strategies. These worked in concert to protect the community from outsiders and keep internal groups physically segregated. The fortifications are discussed in relation to local political organization and a martial aesthetic in northern Peru during the period. Recuay elite identity and monumentalism arose out of local corporate traditions of hilltop dwelling and defence. Although such traditions are now largely absent in contemporary patterns of settlement, an archaeology of warfare at Yayno has repercussions for local understandings of the past. By now, it is axiomatic, albeit still highly provocative, promote recognition and judicious understandings of to assert that armed conflict contributed significantly warfare culture by describing the logic and historical to shaping the cultures of many past and present place of its practice. human societies (Keeley 1996; LeBlanc 2003). Quite This article examines the defensive works at rightly, it remains a sensitive topic for living descend- Yayno, a fortified centre in Peru’s north-central high- ants of groups and source communities, whose past lands, Department of Ancash (Fig. 1). It was very likely and histories are characterized as warlike or their cul- the seat of a powerful chiefly society in the Recuay tures under scrutiny as having related practices such tradition, cal. -

The Pyramid of Doom: an Ancient Murder Mystery

to master the science of irrigation. Where else in the world is irrigation Sciences in Roanoke, Virginia, a page on “Human Sacrifices at the practiced? Have you ever seen an irrigated field? How is irrigation done? Huaca de la Luna.” • It has been estimated that the Pyramid of the Sun contains more than 50 million adobe bricks. How do you think the Moche were able to Other Resources accomplish such a feat? What does that tell you about the way in which their society was organized? Does the fact that some Moche burials For students: were done with a level of luxury that far surpassed other Moche burials Alva, Walter. “The Moche of Ancient Peru. New Tomb of Royal indicate to you that the Moche lords had unusual power? Splendor,” National Geographic Magazine, 177, 6 (1990), pp. 2-15. •One of the largest problems faced by archaeologists today is the Boehm, David A. Peru in Pictures. Lerner, 1997. activities of looters who find archaeological sites before the Falconer, Kieran. Peru (Cultures of the World). Benchmark, 1996. archaeologists do and remove the treasures. Since these treasures are King, David C. Peru : Lost Cities, Found Hopes (Exploring Cultures of eventually sold, what harm do looters do? What are some ways that the World). Benchmark, 1997. looting can be discouraged? MUMMIES AND PYRAMIDS: •Archaeologists were able to learn about what Moche customs may have For adults: EGYPT AND BEYOND been by observing a ritual combat among Andean villagers in 1995. How Bawden, Garth. The Moche. Blackwell Publishers, 1996. do you think this custom was preserved for such a long time? In what Bonavia, Duccio. -

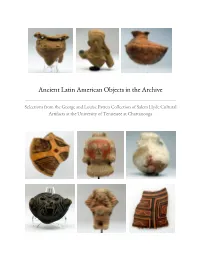

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive

Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Ancient Latin American Objects in the Archive: Selections from the George and Louise Patten Collection of Salem Hyde Cultural Artifacts at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga An exhibition catalog authored by students enrolled in Professor Caroline “Olivia” M. Wolf’s Latin American Visual Culture from Ancient to Modern class in Spring 2020. ● Heather Allen ● Abby Kandrach ● Rebekah Assid ● Casper Kittle ● Caitlin Ballone ● Jodi Koski ● Shaurie Bidot ● Anna Lee ● Katlynn Campbell ● Peter Li ● McKenzie Cleveland ● Sammy Mai ● Keturah Cole ● Amber McClane ● Kyle Cumberton ● Silvey McGregor ● Morgan Craig ● Brcien Partin ● Mallory Crook ● Kaitlyn Seahorn ● Nora Fernandez ● Cecily Salyer ● Briana Fitch ● Stephanie Swart ● Aaliyah Garnett ● Cameron Williams ● Hailey Gentry ● Lauren Williamson ● Riley Grisham ● Hannah Wimberly Lowe ● Chelsey Hall © 2020 by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 5 A Collaborative Approach to Undergraduate Research 6 A Note on the Collection 7 Animal Figures 8 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Figure 10 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Monkey Figurine 11 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Sherd 12 Pre-Columbian Ceramic Bird-Shaped Whistle 13 Anthropomorphic Ceramics 14 Pre-Columbian Vessel Sherd 15 Pre-Columbian Handle Sherd 17 Pre-Columbian Panamanian Ceramic Vessel with Decorated -

Chapter Introduction

Chapter 1: New World Beginnings Chapter Introduction ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning Chapter Introduction I have come to believe that this is a mighty continent which was hitherto unknown. Your Highnesses have an Other World here. Chritopher Columu , 1498 Several billion years ago, that whirling speck of cosmic dust known as the earth, fifth in size among the planets, came into being. About six thousand years ago—only a minute in geological time—recorded history of the Western world began. Certain peoples of the Middle East, developing a written culture, gradually emerged from the haze of the past. Five hundred years ago—only a few seconds figuratively speaking—European explorers stumbled on the Americas. This dramatic accident forever altered the future of both the Old World and the New, and of Africa and Asia as well (see Figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 The Arc of Time © 2016 Cengage Learning Chapter 1: New World Beginnings Chapter Introduction ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning © 2016 Cengage Learning Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may by reproduced or used in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, or in any other manner - without the written permission of the copyright holder. Chapter 1: New World Beginnings: 1.1 The Shaping of North America ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning 1.1 The Shaping of North America Planet earth took on its present form slowly. -

Lost Languages of the Peruvian North Coast LOST LANGUAGES LANGUAGES LOST

12 Lost Languages of the Peruvian North Coast LOST LANGUAGES LANGUAGES LOST ESTUDIOS INDIANA 12 LOST LANGUAGES ESTUDIOS INDIANA OF THE PERUVIAN NORTH COAST COAST NORTH PERUVIAN THE OF This book is about the original indigenous languages of the Peruvian North Coast, likely associated with the important pre-Columbian societies of the coastal deserts, but poorly documented and now irrevocably lost Sechura and Tallán in Piura, Mochica in Lambayeque and La Libertad, and further south Quingnam, perhaps spoken as far south as the Central Coast. The book presents the original distribution of these languages in early colonial Matthias Urban times, discusses available and lost sources, and traces their demise as speakers switched to Spanish at different points of time after conquest. To the extent possible, the book also explores what can be learned about the sound system, grammar, and lexicon of the North Coast languages from the available materials. It explores what can be said on past language contacts and the linguistic areality of the North Coast and Northern Peru as a whole, and asks to what extent linguistic boundaries on the North Coast can be projected into the pre-Columbian past. ESTUDIOS INDIANA ISBN 978-3-7861-2826-7 12 Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Preußischer Kulturbesitz | Gebr. Mann Verlag • Berlin Matthias Urban Lost Languages of the Peruvian North Coast ESTUDIOS INDIANA 12 Lost Languages of the Peruvian North Coast Matthias Urban Gebr. Mann Verlag • Berlin 2019 Estudios Indiana The monographs and essay collections in the Estudios Indiana series present the results of research on multiethnic, indigenous, and Afro-American societies and cultures in Latin America, both contemporary and historical.