Ivo Van Hove's Theatre Laid Bare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

Biographies (396.2

ANTONELLO MANACORDA conducteur italien • Formation o études de violon entres autres avec Herman Krebbers à Amsterdam o puis, à partir de 2002, deux ans de direction d’orchestre chez Jorma Panula. • Orchestres o 1997 : il crée, avec Claudio Abbado, le Mahler Chamber Orchestra o 2006 : nommé chef permanent de l’ensemble I Pomeriggi Musicali à Milaan o 2010 : nommé chef permanent du Kammerakademie Potsdam o 2011 : chef permanent du Gelders Orkest o Frankfurt Radio Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Sydney Symphony, Orchestra della Svizzera Italia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Stavanger Symphony, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Hamburger Symphoniker, Staatskapelle Weimar, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse & Gothenburg Symphony • Fil rouge de sa carrière o collaboration artistique de longue durée avec La Fenice à Venise • Pour la Monnaie o dirigeerde in april 2016 het Symfonieorkest van de Munt in werk van Mozart en Schubert • Projets récents et futurs o Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Don Giovanni & L’Africaine à Frankfort, Lucio Silla & Foxie! La Petite Renarde rusée à la Monnaie, Le Nozze di Figaro à Munich, Midsummer Night’s Dream à Vienne et Die Zauberflöte à Amsterdam • Discographie sélective o symphonies de Schubert avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical - courroné par Die Welt) o symphonies de Mendelssohn également avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical) • Pour en savoir plus o http://www.inartmanagement.com o http://www.antonello-manacorda.com CHRISTOPHE COPPENS Artiste et metteur -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 02-269.24.19 Cats - 10.6.19 Cover Blue- Retro.indd Man Group 1 @ Pantages 9-6.indd 1 9/10/199/10/19 10:18 1:19 AMPM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE BMGNET Touring, LLC presents Written by JONATHAN KNIGHT MICHAEL DAHLEN BLUE MAN GROUP Composers ANDREW SCHNEIDER JEFF TURLIK Blue Men MERIDIAN MIKE BROWN STEVEN WENDT ADAM ZUICK Musicians CORKY GAINSFORD ROBERT GOMEZ JERRY KOPS Set Designer Lighting Designer Costume Designer Sound Designer JASON ARDIZZONE-WEST JEN SCHRIEVER EMILIO SOSA CREST FACTOR Video Designer Blue Man Character Costumes SFX Designer LUCY MACKINNON PATRICIA MURPHY BILL SWARTZ Creative Director Production Stage Manager Music Director JONATHAN KNIGHT RICHARD HERRICK BYRON ESTEP Company Manager Production Stage Manager Head Carpenter STACY MYERS ANNA K. RAINS ZACHARY FEIVOU General Management Tour Booking, Marketing Production Management GENTRY & ASSOCIATES and Publicity Direction NETWORKS PRESENTATIONS GREGORY VANDER PLOEG BOND THEATRICAL GROUP WALKER WHITE Line Producer Executive Producers JENNIE RYAN BENOIT MATHIEU & SETH WENIG Directed by JENNY KOONS Original Creators - MATT GOLDMAN, PHIL STANTON, CHRIS WINK A CIRQUE DU SOLEIL Entertainment Group and NETWORKS Presentation Additional Music Composer and Collaborators - Lotic, Holly Original Direction by Blue Man Group and Marlene Swartz Original Executive Producer - Maria Di Dia Original Associate Producers - Akie Kimura Topal & Broadway Line Company Original New York production presented in a workshop production at La MaMa E.T.C. blueman.com 4 PLAYBILL 9.24.19 - 10.6.19 Blue Man Group @ Pantages 9-6.indd 2 9/10/19 1:19 PM WHO’S WHO MERIDIAN (Blue Man Captain) received his company. -

Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 Nationaltheatre.Org.Uk Find Us Online How to Book the Plays

This cover was created with the Lighting Department. Lighting is used to create moments of stage magic. The choices a Lighting Designer makes about how a set and actors are lit have a major impact on the mood and atmosphere of a scene. The National’s Lighting department deploys everything from flood or spotlight to complex automated lights, controlled via a lighting data network. Sep 16 – Feb 17 020 7452 3000 nationaltheatre.org.uk Find us online How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm See p29 for Sunday and holiday opening times Hedda Gabler LOVE Amadeus Playing from 5 December 6 December – 10 January Playing from 19 October Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm for the following week’s performances Day Tickets £15 / £18 tickets available in person on the day of the performance No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Peter Pan The Red Barn A Pacifist’s Guide to Playing from 16 November 6 October – 17 January the War on Cancer 14 October – 29 November Access symbols used in this brochure Captioned Touch Tour British Sign Language Relaxed Performance Audio-Described TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre NT Future is Partner for Sponsored by in partnership -

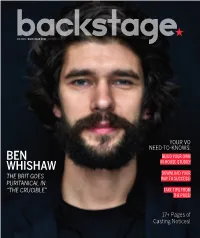

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

The Tragedies: V. 2 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE TRAGEDIES: V. 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Shakespeare,Tony Tanner | 770 pages | 07 Oct 1993 | Everyman | 9781857151640 | English | London, United Kingdom The Tragedies: v. 2 PDF Book Many people try to keep them apart, and several lose their lives. Often there are passages or characters that have the job of lightening the mood comic relief , but the overall tone of the piece is quite serious. The scant evidence makes explaining these differences largely conjectural. The play was next published in the First Folio in Distributed Presses. Officer involved with Breonna Taylor shooting says it was 'not a race thing'. Share Flipboard Email. Theater Expert. In tragedy, the focus is on the mind and inner struggle of the protagonist. Ab Urbe Condita c. The 10 Shakespeare plays generally classified as tragedy are as follows:. University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 6 January President Kennedy's sister, Rosemary Kennedy , had part of her brain removed in in a relatively new procedure known as a prefrontal lobotomy. The inclusion of comic scenes is another difference between Aristotle and Shakespearean tragedies. That is exactly what happens in Antony and Cleopatra, so we have something very different from a Greek tragedy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, , An Aristotelian Tragedy In his Poetics Aristotle outlines tragedy as follows: The protagonist is someone of high estate; a prince or a king. From the minute Bolingbroke comes into power, he destroys the faithful supporters of Richard such as Bushy, Green and the Earl of Wiltshire. Shakespearean Tragedy: Shakespearean tragedy has replaced the chorus with a comic scene. The Roman tragedies— Julius Caesar , Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus —are also based on historical figures , but because their source stories were foreign and ancient they are almost always classified as tragedies rather than histories. -

Leisure, Idleness, and Virtuous Activity in Shakespearean Drama Ed Taft Marshall University, [email protected]

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Literary Magazines Conference November 2014 Leisure, Idleness, and Virtuous Activity in Shakespearean Drama Ed Taft Marshall University, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Taft, Ed (2008) "Leisure, Idleness, and Virtuous Activity in Shakespearean Drama," Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference: Vol. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc/vol2/iss2008/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Literary Magazines at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Leisure, Idleness, and Virtuous Activity in Shakespearean Drama Unhae Langis Leisure, Idleness, and Virtuous Activity in Shakespearean Drama by Unhae Langis The topoi leisure and idleness abound in Shakespearean drama in complex manifestations, replete with class and gender inflections. The privileged term, leisure, modeled after Greek skolé, refers to the “opportunity afforded by freedom from occupations” (OED 2a), as enjoyed by the nobles who, excused from sustenance labor, could ideally devote themselves to “the development of virtue and the performance of political duties” (Aristotle, Politics VII.9.1328b33-a2). -

THE MYSTERY of LOVE & SEX Cast Announcement

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE MAMOUDOU ATHIE, DIANE LANE, GAYLE RANKIN, TONY SHALHOUB TO BE FEATURED IN LINCOLN CENTER THEATER’S PRODUCTION OF “THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX” A new play by BATHSHEBA DORAN Directed by SAM GOLD PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2015 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, MARCH 2, 2015 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop, Producing Artistic Director) has announced that Mamoudou Athie, Diane Lane, Gayle Rankin, and Tony Shalhoub will be featured in its upcoming production of THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX, a new play by Bathsheba Doran. The production, which will be directed by Sam Gold, will begin previews Thursday, February 5 and open on Monday, March 2 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Deep in the American South, Charlotte and Jonny have been best friends since they were nine. She's Jewish, he's Christian, he's black, she's white. Their differences intensify their connection until sexual desire complicates everything in surprising, compulsive ways. An unexpected love story about where souls meet and the consequences of growing up. THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX will have sets by Andrew Lieberman, costumes by Kaye Voyce, lighting by Jane Cox, and original music and sound by Daniel Kluger. BATHSHEBA DORAN’s plays include Kin, also directed by Sam Gold (Playwrights Horizons), Parent’s Evening (Flea Theater), Ben and the Magic Paintbrush (South Coast Repertory Theatre), Living Room in Africa (Edge Theater), Nest, Until Morning, and adaptations of Dickens’ Great Expectations, Maeterlinck’s The Blind, and Peer Gynt. -

Rome in Shakespeare's Tragedies

Chronotopos A Journal of Translation History Angela Tiziana Tarantini & Christian Griffiths Introduction to by De Lorenzo. How Shakespearean Material was appropriated by Translators and Scholars during Romethe Fascist in Shakespeare’s Period. Tragedies 2/2019 Abstract DOI: 10.25365/cts-2019-1-2-8 Herausgegeben am / Éditée au / What follows is a prefatory commentary and an English Edited at the: Zentrum für translation of the critical introduction to the text Roma Translationswissenschaft der nelle tragedie di Shakespear Universität Wien Tragedies) published in Italy in 1924. The book contains the translations of Julius Caesare (Rome and inCoriolanus Shakespeare’s, both ISSN: 2617-3441 carried out by Ada Salvatore, and an introductory essay written by Giuseppe De Lorenzo. Our aim in translating the introductory essay by De Lorenzo is to raise awareness among non-Italian speaking scholars of how Shakespearian material was appropriated through translation by translators and intellectuals during the Fascist era. Keywords: translation, Shakespeare, fascism, Italy Zum Zitieren des Artikels Tarantini, Angela Tiziana & Griffiths, Christian (2019): Introduction to by De Lorenzo. How Shakespearean/ Pour Material citer l’article was appropriate / To cite thed by article: Translators and Scholars during the Fascist Period, Chronotopos 2 (1), 144-177. DOI: 10.25365/cts-2019-1-2-8 Rome in Shakespeare’s Tragedies Angela Tiziani Tarantini & Christian Griffiths: Introduction to Rome in Shakespeare’s Tragedies by DeLorenzo. Angela Tiziana Tarantini & Christian Griffiths Introduction to Rome in Shakespeare’s Tragedies by De Lorenzo. How Shakespearean Material was appropriated by Translators and Scholars during the Fascist Period Abstract What follows is a prefatory commentary and an English translation of the critical introduction to the text Roma nelle tragedie di Shakespeare (Rome in Shakespeare’s Tragedies) published in Italy in 1924. -

Contents. the Tragedy of Cleopatra by Samuel Daniel. Edited by Lucy Knight Editing a Renaissance Play Module Code: 14-7139-00S

Contents. The tragedy of Cleopatra By Samuel Daniel. Edited by Lucy Knight Editing a Renaissance Play Module Code: 14-7139-00S Submitted towards MA English Studies January 11th, 2011. 1 | P a g e The Tragedy of Cleopatra Front matter Aetas prima canat veneres, postrema tumultus.1 To the most noble Lady, the Lady Mary Countess of Pembroke.2 Behold the work which once thou didst impose3, Great sister of the Muses,4 glorious star5 Of female worth, who didst at first disclose Unto our times what noble powers there are In women’s hearts,6 and sent example far, 5 To call up others to like studious thoughts And me at first from out my low repose7 Didst raise to sing of state and tragic notes8, Whilst I contented with a humble song Made music to myself that pleased me best, 10 And only told of Delia9 and her wrong And praised her eyes, and plain’d10 mine own unrest, A text from whence [my]11 Muse had not digressed Had I not seen12 thy well graced Antony, Adorned by thy sweet style in our fair tongue 15 1 ‘Let first youth sing of Venus, last of civil strife’ (Propertius, 2.10.7). This quote is a reference to the Classical ‘Cursus,’ which state that you graduate from writing poetry to writing tragedy. Daniel is saying he wrote love poetry in his youth but now Mary Sidney has given him the courage to aspire to greater things, i.e. tragedy. 2 Mary Sidney. See Introduction, ‘Introductory dedication: Mary Sidney and family’.