Visual Media Use and Intermediality in Shakespeare Productions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Five Children and It

Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Released Friday 15 October 2004 - Scotland Only Released Friday 22 October 2004 - Nationwide For further information please contact: Emily Carr [email protected] Victoria Keeble [email protected] Bella Gubay [email protected] 020 7426 5700 Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Capitol Films and the UK Film Council present in association with the Isle of Man Film Commission and in association with Endgame Entertainment a Jim Henson Company Production a Capitol Films / Davis Films Production Written by: David Solomons Produced by: Nick Hirschkorn Lisa Henson Samuel Hadida Directed by: John Stephenson FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Cast List It .............................................................................. Eddie Izzard Cyril......................................................................... Jonathan Bailey Anthea...................................................................... Jessica Claridge Robert ...................................................................... Freddie Highmore Jane.......................................................................... Poppy Rogers The Lamb................................................................. Alec & Zak Muggleton Horace...................................................................... Alexander Pownall Uncle Albert............................................................. Kenneth Branagh Martha...................................................................... Zoë Wanamaker Father...................................................................... -

Jan Pester 10X40 Neo`Noir TV Comedy Starring:- Uma Thurman

Jan Pester Director of Photography Features & Television Drama PRODUCTION DIRECTOR COMPANY FEATURES & MAJOR TELEVISION Adam Brooks Universal Cable Prod IMPOSTERS for Bravo 10x40 Neo`Noir TV Comedy Starring:- Uma Thurman, Inbar Lavi,Rob Heaps THE LADY IN THE VAN Nicholas Hytner BBC Films 2nd Unit Feature Film- Comedy Starring:- Dame Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent James Corden, Alex Jennings,Dominic Cooper THE SECRET AGENT BBC 2nd Unit Charles 2 x 60 Mins McDougall Starring:- Toby Jones, Ash Hunter, Vicky McClure SWANSONG Douglas Ray Contented Productions Feature Film Productions M Comedy Thriller Starrng:- Eva Birthistle, Paul Hilton Antonia Campbell-Hughes, Matt Berry GARY: TANK COMMANDR Comedy drama series Starring: Greg McHugh, Scott Fletcher THE WICKER TREE Robert Hardy British Lion Films Horror Feature – RED 4k Part of Robin Hardy’s “Wicker Man Trilogy” based on his eerie 1973 film The “Wicker Man” Starring: Sir Christopher Lee, Suzie Amy, Honeysuckle Weeks, Brittania Nicol, Henry Garrett, Graham McTavish http://thewickertreemovie.com DINOSAPIEN David Winning Alberta Filmworks / BBC Major International Drama series shot on HD in Alberta Brendon Canada. Sheppard Starring: Brittney Wilson, Alexandra Gingras, Brendan Dean Bennett Meyer Pat Williams EMMY Nomination “Outstanding Achievement in Single Camera Camera Photography” Winner, Gold, Worldfest, Houston, 2007 Winner, Silver Plaque, Chicago, 2007 Hugo Television Awards HOGFATHER Vadim Jean The Mob Film Co High Profile Fantasy Action Drama Shot on Arri D20 for Sky One Starring: David -

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Digital Playbill

IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE Little Gem BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE CHARLOTTE MOORE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | CIARÁN O’REILLY, PRODUCING DIRECTOR A PERFORMANCE ON SCREEN LITTLE GEM BY ELAINE MURPHY DIRECTED BY MARC ATKINSON BORRULL STARRING BRENDA MEANEY, LAUREN O'LEARY AND MARSHA MASON scenic design costume design lighting design sound design & original music sound mix MEREDITH CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL RYAN M.FLORIAN RIES METZGER O'CONNOR RUMERY STAAB edited by production coordinator production coordinator SARAH ARTHUR REBECCA NICHOLS ATKINSON MONROE casting press representatives general manager DEBORAH BROWN MATT ROSS LISA CASTING PUBLIC RELATIONS FANE TIME & PLACE North Dublin, 2008 Running Time: 90 minutes, no intermission. SPECIAL THANKS Irish Repertory Theatre wishes to thank Henry Clarke, Olivia Marcus, Melanie Spath, and the Howard Gilman Foundation. Little Gem is produced under the SAG-AFTRA New Media Contract. THE ORIGINAL 2019 PRODUCTION OF LITTLE GEM ALSO FEATURED PROPS BY SVEN HENRY NELSON AND SHANNA ALISON AS ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER. THIS PRODUCTION IS MADE POSSIBLE WITH PUBLIC FUNDS FROM THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, THE NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, AND OTHER PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS AND CORPORATIONS, AND WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE MANY GENEROUS MEMBERS OF IRISH REPERTORY THEATRE’S PATRON’S CIRCLE. WHO’S WHO IN THE CAST MARSHA MASON (Kay) has summer 2019, Marsha starred in Irish received an Outer Critics Rep’s acclaimed production of Little Gem Circle Award and 4 Academy and directed a reading of The Man Who Awards nominations for her Came to Dinner with Brooke Shields and roles in the films “The Goodbye Walter Bobbie at the Bucks County Girl,” “Cinderella Liberty,” Playhouse and WP Theater in NYC. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Biographies (396.2

ANTONELLO MANACORDA conducteur italien • Formation o études de violon entres autres avec Herman Krebbers à Amsterdam o puis, à partir de 2002, deux ans de direction d’orchestre chez Jorma Panula. • Orchestres o 1997 : il crée, avec Claudio Abbado, le Mahler Chamber Orchestra o 2006 : nommé chef permanent de l’ensemble I Pomeriggi Musicali à Milaan o 2010 : nommé chef permanent du Kammerakademie Potsdam o 2011 : chef permanent du Gelders Orkest o Frankfurt Radio Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Sydney Symphony, Orchestra della Svizzera Italia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Stavanger Symphony, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Hamburger Symphoniker, Staatskapelle Weimar, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse & Gothenburg Symphony • Fil rouge de sa carrière o collaboration artistique de longue durée avec La Fenice à Venise • Pour la Monnaie o dirigeerde in april 2016 het Symfonieorkest van de Munt in werk van Mozart en Schubert • Projets récents et futurs o Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Don Giovanni & L’Africaine à Frankfort, Lucio Silla & Foxie! La Petite Renarde rusée à la Monnaie, Le Nozze di Figaro à Munich, Midsummer Night’s Dream à Vienne et Die Zauberflöte à Amsterdam • Discographie sélective o symphonies de Schubert avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical - courroné par Die Welt) o symphonies de Mendelssohn également avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical) • Pour en savoir plus o http://www.inartmanagement.com o http://www.antonello-manacorda.com CHRISTOPHE COPPENS Artiste et metteur -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Noteworthy Spring 2016

noteworthy news from the university of toronto libraries Spring 2016 Lana Peters is the name adopted by Svetlana Alliluyeva, daughter of Josef Stalin IN THIS ISSUE Spring 2016 12 “35 years of Degrassi” event exhorts audience to “just do it” [ 3 ] Taking Note [ 11 ] Other Events [ 4 ] Going for Gold: 50 Years of the University of Toronto Archives [ 12 ] Friends of the Libraries Lecture Series [ 5 ] Understanding Canada’s Oldest Profession [ 12 ] Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library Events [ 6 ] Eureka! U of T Music Librarian Chances on Long-lost Treasure [ 14 ] Supporting Scientific Research [ 6 ] Ursula Franklin Collection at UTARMS [ 15 ] Exhibitions and Events [ 7 ] Renowned Philosopher Donates Books and Archives to UTL Special Collections [ 8 ] Rare Times at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library Cover image: Letters written by Josef Stalin’s daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva. Above: Degrassi’s Linda Schuyler hams it up with fans at a Friends of the Libraries Lecture. [ 2 ] TAKING NOTE noteworthy news from the university of toronto libraries WELCOME TO THE SPRING ISSUE In 2009, the founder of the worldwide Chief Librarian of Noteworthy. Our cover presents a fascinat- web, Tim Berners-Lee, gave a TED talk Larry P. Alford ing recent acquisition of the letters of about Linked Data, essentially calling for Editor Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, to a action on the transition from documents to Megan Campbell friend over a couple of decades before her data on the web. In practical terms, this death, through which the devastating means publishing information online in a Designer Maureen Morin effects of her father’s legacy may be under- way that can connect to other web resources. -

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2014 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Tom McCamus, Seana McKenna Support for the 2014 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by Karon Bales & Charles Beall Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast ............................................................................................... 10 Lesson Plans and Activities Creating Atmosphere .......................................................................................... 11 Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition! ........................................................ 14 Discussion Topics .............................................................................................. -

Samantha Saltzman Resume

3569 Broadway, Apt 4E, New York, NY 10031 - (781) 354-0402 - [email protected] www.samanthasaltzman.com Broadway/Off-Broadway/Touring The King & I Directed by Shelley Butler 2nd National Tour Assistant Director Based on original direction by Bartlett Sher • Participated in character conversations with new principals and taught blocking in preparation for rehearsals with the director • Assisted in the recreation of original staging and dramaturgy from prompt book and documentation • Coached child actors on acting intention, review of blocking, and accent reinforcement • Trained understudies and stand-by principals and ran their rehearsals and put-ins • Sent out at regular intervals to check on and maintain the production and performances Lady in the Dark Directed by Ted Sperling New York City Center Associate Director • Oversaw and advised on Tech process and implementation, including scheduling and prioritizing creative needs in limited time frame • Responsible for taking and distributing notes to creative team and actors • Advised script adaptation and oversaw collation and implementation of changes Matilda the Musical Directed by Matthew Warchus 1st National Tour Resident Director • Traveled with the show for six months • Trained over 40 understudies and new cast members and ran rehearsals and put-ins for new cast • Regularly maintained child cast with notes and brush up rehearsals • Responsible for show coverage, including Matildas’ pre-show warm-ups and delivery of notes between shows and in rehearsals to full company Assistant -

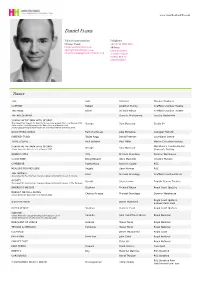

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard