Changing Patterns of Acceptance. International Criminal Justice After the Rwandan Genocide Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORIGINAL: ENGLISH TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Erik Møse

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda ORIGINAL: ENGLISH TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Erik Møse, presiding Judge Jai Ram Reddy Judge Sergei Alekseevich Egorov Registrar: Adama Dieng Date: 18 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. Théoneste BAGOSORA Gratien KABILIGI Aloys NTABAKUZE Anatole NSENGIYUMVA Case No. ICTR-98-41-T JUDGEMENT AND SENTENCE Office of the Prosecutor: Counsel for the Defence: Barbara Mulvaney Raphaël Constant Christine Graham Allison Turner Kartik Murukutla Paul Skolnik Rashid Rashid Frédéric Hivon Gregory Townsend Peter Erlinder Drew White Kennedy Ogetto Gershom Otachi Bw’Omanwa The Prosecutor v. Théoneste Bagosora et al., Case No. ICTR-98-41-T TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 1 1. Overview ................................................................................................................... 1 2. The Accused ............................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Théoneste Bagosora ................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Gratien Kabiligi ....................................................................................................... 10 2.3 Aloys Ntabakuze ...................................................................................................... 10 2.4 Anatole Nsengiyumva ............................................................................................. -

ICTR-2001-73-T the PROSECUTOR CHAMBER III of the TRIBUNAL V

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA CASE NO. : ICTR-2001-73-T THE PROSECUTOR CHAMBER III OF THE TRIBUNAL v. PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO MONDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2005 1502H TRIAL Before the Judges: Inés Monica Weinberg de Roca, Presiding Lee Gacuiga Muthoga Khalida Rachid Khan For the Registry: Mr. Constant K. Hometowu Mr. Sheha Mussa For the Prosecution: Mr. Hassan Bubacar Jallow Mr. Wallace Kapaya Ms. Gina Butler Mr. Iskander Ismail For the Accused Protais Zigiranyirazo: Mr. John Philpot Mr. Peter Zaduk Court Reporters: Ms. Ann Burum Ms. Sherri Knox Ms. Jean Baigent Ms. Judith Baverstock ZIGIRANYIRAZO MONDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2005 I N D E X WITNESS For the Prosecution: ZUHDI JANBEK Examination-in-chief by Mr. Kapaya .......................................................................................................... 21 EXHIBITS Exhibit No. P. 1E and P. 1F ....................................................................................................................... 25 Exhibit No. P. 2 .......................................................................................................................................... 26 ANN BURUM - ICTR - TRIAL CHAMBER III - page i ZIGIRANYIRAZO MONDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2005 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 MADAM PRESIDENT: 3 Mr. Jallow. 4 MR. JALLOW: 5 Thank you very much. If it pleases the Court, My Lords, the Accused who is -- stands before us today, 6 Protais Zigiranyirazo, is charged with conspiracy to commit genocide, with genocide or, in the 7 alternative, complicity in genocide, crimes against humanity by extermination and murder, by virtue of 8 his responsibility under Article 6(1) of the statute of the Tribunal. 9 10 Your Honours, genocide and conspiracy to commit it and complicity in it are never an act of a single 11 individual but one of several, even many, individuals. This particular article obliges us, the Prosecution, 12 to prove individual responsibility of the Accused, and this we expect to do through the witnesses whom 13 we will be presenting before the Court. -

Downloaded License

journal of international peacekeeping 22 (2018) 40-59 JOUP brill.com/joup Rwanda’s Forgotten Years Reconsidering the Role and Crimes of Akazu 1973–1993 Andrew Wallis University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract The narrative on the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda has become remark- able in recent years for airbrushing the responsibility of those at its heart from the tragedy. The figure of President Juvenal Habyarimana, whose 21-year rule, along with the unofficial network based around his wife and family, the Akazu, has been largely marginalised. Yet to understand April 1994 requires a far longer-term understanding. Those responsible had grown their power, influence and ambition for decades inside every part of Rwandan society after seizing power in their coup of 1973; they had estab- lished personal and highly lucrative bonds with European and North American coun- tries, financial institutions and the Vatican, all of whom variously assisted with finan- cial, political, diplomatic and military support from 1973 into 1994. This chapter seeks to outline how Akazu built its powerbase, influence and ambition in the two decades before 1994 and the failure of its international backers to respond to repeated warning signs of a tragedy foretold. Keywords genocide – Akazu – Habyarimana – Parmehutu – Network Zero The official Independence Day celebrations that got underway on Sunday 1 July 1973 came as Rwanda teetered on the edge of an expected coup. Eleven years after independence the one party regime of President Grégoire Kayiban- da was imploding. Hit by economic and political stagnation, notably the dam- aging failure to share the trappings of power with those outside his central © Andrew Wallis, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18754112-0220104004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded License. -

1'}..13 1&3 -I"'O~ ~ International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda

rc.,7/i- J!XJI ..:??-Z 5-'I.. ~C3 1'}..13 1&3 -I"'O~ ~ INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA Case No. ICTR·2001·73·I ~{ c.::::> THE PROSECUTOR ~ AGAINST PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO ANNOTATED AMENDED INDICTMENT The Prosecutor of the International Tribunal for Rwanda, pursuant to the authority stipulated in Article 17 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (the "Statute of the Tribunal") charges PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO with I CONSPIRACY TO COMMIT GENOCIDE in terms of Article 2(3)(b) of the Statute of the Tribunal; II GENOCIDE, pursuant to Article 2(3)(a) of the Statute of the Tribunal; alternatively III COMPLICITY IN GENOCIDE, pursuant to Article 2(3)(e) of the Statute of the Tribunal; IV EXTERMINATION, as a CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY pursuant to Article 3(a) of the Statute of the Tribunal; and V MURDER, as a CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY, pursuant to Article 3(b) of the Statute of the Tribunal. THE ACCUSED 1 Protais ZIGIRANYIRAZO, alias Mr. "Z", was born in 1938 in Giciye commune, Gisenyi Prefecture, Rwanda. Giciye together with the adjoining commune of Karago constitutes Bushiro which is also the birthplace of former President of Rwanda Juvenal HABYARIMANA and his wife, Agathe KANZIGA. Protais ZIGIRANYIRAZO is Agathe KANZIGA's brother, hence the brother-in-law of President HABYARIMANA. 1 2 Protais ZIGIRANYIRAZO served the 2nd Republic MRND government of Juvenal HABYARIMANA as prefet of Ruhengeri prefecture from 1974 to 1989. During the events cited in this indictment he was a businessman in Giciye commune. THE CHARGES 3 At all times referred to in this indictment there existed in Rwanda a minority ethnic group known as Tutsis, officially identified as such by the government. -

Appeals Judgement

Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron, Presiding Judge Mehmet Güney Judge Fausto Pocar Judge Liu Daqun Judge Carmel Agius Registrar: Mr. Adama Dieng Judgement of: 16 November 2009 PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO v. THE PROSECUTOR Case No. ICTR-01-73-A JUDGEMENT Counsel for Protais Zigiranyirazo: Mr. John Philpot Mr. Peter Zaduk Ms. Fiona Gray Mr. Kyle Gervais The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Hassan Bubacar Jallow Mr. Alex Obote-Odora Ms. Christine Graham Ms. Linda Bianchi Ms. Béatrice Chapaux Mr. Alfred Orono Orono I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................. 1 B. THE APPEALS ............................................................................................................................... 2 II. STANDARDS OF APPELLATE REVIEW ............................................................................... 3 III. APPEAL OF PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO ........................................................................... 5 A. ALLEGED ERRORS IN EVALUATING THE ALIBI (GROUNDS 6 AND 12) ........................................... 5 1. Burden of Proof in the Assessment of Alibi ............................................................................ 5 2. Alleged Errors in Evaluating -

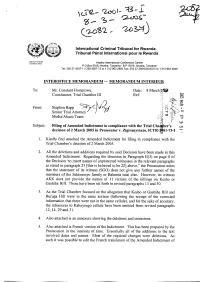

Amended Indictment of 31 August2004 Without the Needto Sendthe New Amendedindictment of the Languagesection

InternationalCriminal Tribunal for Rwanda TribunalPénal Internationalpour le Rwanda UNITEDNATIONS NATIONSUNIES ArushaInternational Conference Centre P.O.Box6016, Arusha, Tanzania - B.P.6016, Arusha, Tanzanie Tel:255 27 4207-11/2504367-72 or 1 212 963 2850Fax: 255 27 2504000/4373or 1 212 963 2848 INTEROFFICE MEMORANDUM -- MEMORANDUM INTERIEUR To" Mr. ConstantHometowu Date: 8 March~{~1~ U Coordinator,Trial Chamber III Ref: () ! From: StëPô:TrîâïPtto~’e~y~(~, )~¢ . r2J ~ Media/AkazuTeam J~,53 -0 Subject: Filingof AmendedIndictment in compliancewith the TrialCha~tber’s o’i decisionof 2 March2005 in Prosecutorv. Zigiranyirazo,ICTR-~01-73-I -- oe 1. Kindlyfind attached the AmendedIndictment for filingin compliancewith the TrialChamber’s decision of 2 March2005. 2. Ailthe deletions and additions required by saidDecision have been made in this AmendedIndictment. Regarding the directionin ParagraphII(3) on page8 theDecision "to insert names of unprotectedwitnesses in therelevant paragraphs as statedin paragraph25 [thisis believedto be 22]above," the Prosecution notes thatthe statementof its witness(SGO) does not giveany furthernames of the membersof the Sekimonyofamily or Bahomatutsi clan. However, its witness AKK does not providethe namesof 11 victimsof the killingson Keshoor GashiheHill. These have been set forth in revisedparagraphs 13 and30. 3. As the TrialChamber focused on theallegation that Kesho or GashiheHill and RumgaHill were in the samesecteur (following the receiptof the corrected informationthat there were not in thesame cellule), and for the sake of accuracy, the referencesto Kabayengocellule have been omitted from revised paragraphs 12,14, 29 and31. 4, Alsoattached is an annexureshowing the deletions and omissions. 5. Alsoattached is Frenchversion of theIndictment. This has been prepared by the Prosecutionin the interests of time.Essentially ail of theadditions to thetext involveddates and names.Most of the requiredchanges were deletions. -

General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/62/284–S/2007/502 General Assembly Distr.: General 21 August 2007 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-second session Sixty-second year Item 76 of the provisional agenda* Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens Responsible for Genocide and Other Such Violations Committed in the Territory of Neighbouring States between 1 January and 31 December 1994 Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens Responsible for Genocide and Other Such Violations Committed in the Territory of Neighbouring States between 1 January and 31 December 1994 Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly and to the members of the Security Council the twelfth annual report of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Genocide and Other Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Rwanda and Rwandan Citizens Responsible for Genocide and Other Such Violations Committed in the Territory of Neighbouring States between 1 January and 31 December 1994, submitted by the President of the International Tribunal for Rwanda in accordance with article 32 of its statute (see Security Council resolution 955 (1994), annex), which states: “The President of the International Tribunal for Rwanda shall submit an annual report of the International Tribunal for Rwanda to the Security Council and to the General Assembly.” __________________ * A/62/150. -

Updates from the International and Internationalized Criminal Courts Shaleen Brunsdale American University Washington College of Law

Human Rights Brief Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 7 2009 Updates from the International and Internationalized Criminal Courts Shaleen Brunsdale American University Washington College of Law Kara Karlson American University Washington College of Law Jennifer Goldsmith American University Washington College of Law Laura Jarvis American University Washington College of Law Megan Chapman American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hrbrief Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Brunsdale, Shaleen, Kara Karlson, Jennifer Goldsmith, Laura Jarvis, and Megan Chapman." Updates from the International and Internationalized Criminal Courts." Human Rights Brief 16, no.2 (2009): 40-44. This Column is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Rights Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brunsdale et al.: Updates from the International and Internationalized Criminal Cou UPDATES FROM INTERNATIONAL AND INTERNATIONALIZED CRIMINAL COURTS & TRIBUNALS INTERNATIONA L CRI M INA L commander Radislav Krstic´. He related them victimized only because of their TRIBUNA L FOR THE his experience of being captured by the ethnicity. This ICTY initiative will serve FOR M ER YUGOS L AVIA Bosnian Serb army, the Vojska Repub- as a useful tool for understanding and lika Srpska (VRS), while he was hiding appreciating the atrocities which occurred A New Face in a forest during an attempted escape in the former Yugoslavia and support the from Srebrenica. -

Rwanda's Forgotten Years

journal of international peacekeeping 22 (2018) 40-59 JOUP brill.com/joup Rwanda’s Forgotten Years Reconsidering the Role and Crimes of Akazu 1973–1993 Andrew Wallis University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract The narrative on the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda has become remark- able in recent years for airbrushing the responsibility of those at its heart from the tragedy. The figure of President Juvenal Habyarimana, whose 21-year rule, along with the unofficial network based around his wife and family, the Akazu, has been largely marginalised. Yet to understand April 1994 requires a far longer-term understanding. Those responsible had grown their power, influence and ambition for decades inside every part of Rwandan society after seizing power in their coup of 1973; they had estab- lished personal and highly lucrative bonds with European and North American coun- tries, financial institutions and the Vatican, all of whom variously assisted with finan- cial, political, diplomatic and military support from 1973 into 1994. This chapter seeks to outline how Akazu built its powerbase, influence and ambition in the two decades before 1994 and the failure of its international backers to respond to repeated warning signs of a tragedy foretold. Keywords genocide – Akazu – Habyarimana – Parmehutu – Network Zero The official Independence Day celebrations that got underway on Sunday 1 July 1973 came as Rwanda teetered on the edge of an expected coup. Eleven years after independence the one party regime of President Grégoire Kayiban- da was imploding. Hit by economic and political stagnation, notably the dam- aging failure to share the trappings of power with those outside his central © Andrew Wallis, 2020 | doi:10.1163/18754112-0220104004 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded License. -

Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity

GENOCIDE, WAR CRIMES HUMAN AND CRIMES RIGHTS AGAINST HUMANITY WATCH A Digest of the Case Law of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity A Digest of the Case Law of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-586-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org ii GENOCIDE, WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: A DIGEST OF THE CASE LAW OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR RWANDA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................... iv DEDICATION ....................................................................................................... v FOREWORD ........................................................................................................ -

Appeal Judgement, Para

Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Theodor Meron, Presiding Judge Mehmet Güney Judge Fausto Pocar Judge Liu Daqun Judge Carmel Agius Registrar: Mr. Adama Dieng Judgement of: 16 November 2009 PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO v. THE PROSECUTOR Case No. ICTR-01-73-A JUDGEMENT Counsel for Protais Zigiranyirazo: Mr. John Philpot Mr. Peter Zaduk Ms. Fiona Gray Mr. Kyle Gervais The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Hassan Bubacar Jallow Mr. Alex Obote-Odora Ms. Christine Graham Ms. Linda Bianchi Ms. Béatrice Chapaux Mr. Alfred Orono Orono I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................. 1 B. THE APPEALS ............................................................................................................................... 2 II. STANDARDS OF APPELLATE REVIEW ............................................................................... 3 III. APPEAL OF PROTAIS ZIGIRANYIRAZO ........................................................................... 5 A. ALLEGED ERRORS IN EVALUATING THE ALIBI (GROUNDS 6 AND 12) ........................................... 5 1. Burden of Proof in the Assessment of Alibi ............................................................................ 5 2. Alleged Errors in Evaluating -

Judge Inés Mónica Weinberg De Roca, Presiding Judge Khalida Rachid Khan Judge Lee Gacuiga Muthoga

International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES OR: ENG TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Inés Mónica Weinberg de Roca, presiding Judge Khalida Rachid Khan Judge Lee Gacuiga Muthoga Registrar: Adama Dieng Date: 18 December 2008 THE PROSECUTOR v. Protais ZIGIRANYIRAZO Case No. ICTR-01-73-T JUDGEMENT Office of the Prosecutor: Wallace Kapaya Charity Kagwi-Ndungu Gina Butler Iskandar Ismail Jane Mukangira Counsel for the Accused: John Philpot Peter Zaduk The Prosecutor v. Protais Zigiranyirazo, Case No. ICTR-01-73-T TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 4 1. THE TRIBUNAL AND ITS JURISDICTION ....................................................................... 4 2. THE ACCUSED ............................................................................................................ 4 3. INDICTMENT ............................................................................................................... 5 4. SUMMARY OF PROCEDURAL HISTORY ........................................................................ 5 5. OVERVIEW OF THE CASE ............................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER II: FACTUAL FINDINGS ....................................................................... 7 1. PRELIMINARY MATTERS ............................................................................................. 7 1.1. Judicial Notice ....................................................................................................