Glimpses of History in the Cemetery of Charsadda (Ancient Pushkalavati)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

Mohmad Agency Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL FATA (MOHMAND AGENCY) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH MOHMAND AGENCY 466,984 48,118 AMBAR UTMAN KHEL TEHSIL 62,109 6,799 AMBAR UTMAN KHEL TRIBE 62,109 6799 BAZEED KOR SECTION 21,174 2428 BAHADAR KOR 4,794 488 082050106 695 50 082050107 515 54 082050108 256 33 082050109 643 65 082050110 226 35 082050111 326 39 082050112 425 55 082050113 837 64 082050114 192 24 082050115 679 69 BAZID KOR 8,226 943 082050116 689 71 082050117 979 80 082050118 469 45 082050119 1,062 128 082050120 1,107 145 082050121 655 72 082050122 845 123 082050123 1,094 111 082050124 455 60 082050125 871 108 ISA KOR 3,859 490 082050126 753 93 082050127 1,028 104 082050128 947 118 082050129 715 106 082050130 416 69 KOT MAINGAN 673 79 082050105 673 79 WALI BEG 3,622 428 082050101 401 49 082050102 690 71 082050103 1,414 157 082050104 1,117 151 MAIN GAN SECTION 40,935 4371 AKU KOR 5,478 583 082050223 1,304 117 082050224 154 32 082050225 490 41 082050226 413 40 082050227 1,129 106 082050228 1,988 247 BANE KOR 8,626 1012 Page 1 of 12 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL FATA (MOHMAND AGENCY) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 082050214 1,208 121 082050215 1,363 141 082050216 672 67 082050217 901 99 082050218 1,117 175 082050219 1,507 174 082050220 448 76 082050221 839 79 082050222 571 80 KHORWANDE 1,907 184 082050229 1,714 159 082050230 193 25 MAIN GAN 11,832 1182 082050201 1,209 114 082050202 1,105 124 082050203 1,322 128 082050204 1,387 138 082050205 1,043 75 082050206 774 71 082050207 763 75 082050208 -

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs/ Province: Zabul April 13, 2009 Governor: Mohammad Ashraf Nasseri Provincial Police Chief: Colonel Mohammed Yaqoub Population Estimate: Urban: 9,200 Rural: 239,9001 249,100 Area in Square Kilometers: 17,343 Capital: Qalat (formerly known as Qalat-i Ghilzai) Names of Districts: Arghandab, Baghar, Day Chopan, Jaldak, Kaker, Mizan, Now Bahar, Qalat, Shah Joy, Shamulza’i, Shinkay Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religions: Tribal Groups: Tokhi & Hotaki Majority Pashtun Predominately Sunni Ghilzais, Noorzai &Panjpai Islam Durranis Occupation of Population Major: Agriculture (including opium), labor, Minor: Trade, manufacturing, animal husbandry smuggling Crops/Farming/ Poppy, wheat, maize, barley, almonds, Sheep, goat, cow, camel, donkey Livestock:2 grapes, apricots, potato, watermelon, cumin Language: Overwhelmingly Pashtu, although some Dari can be found, mostly as a second language Literacy Rate Total: 1% (1% male, a few younger females)3 Number of Educational Primary & Secondary: 168 (98% all Colleges/Universities: None, although Institutions: 80 male) 35272 student (99% male), some training centers do exist for 866 teachers (97% male) vocational skills Number of Security Incidents, January: 3 May: 6 September: 7 2007:774 February: 4 June: 8 October: 7 March: 3 July: 8 November: 10 April: 11 August: 5 December: 5 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2006: 3,210ha 2007: 1,611ha NGOs Active in Province: Ibn Sina, Vara, ADA, Red Crescent, CADG Total PRT Projects: 40 Other Aid Projects: 573 Planned Cost: $8,283,665 Planned Cost: $19,983,250 Total Spent: $2,997,860 Total Spent: $1,880,920 Transportation: 1 Airstrip in Primary Roads: The ring road from Ghazni to Kandahar passes through Qalat and Qalat “PRT Air” – 2 flights Shah Joy. -

Pistol Or Revolver

It is hard to believe that the idea of publishing a first-ever digital shooting magazine in Pakistan is becoming a reality. All over the world, shooting as a sport is evolving at a rapid pace. In Pakistan, there is a need for a platform, designed to share knowledge, experiences and opinions of the shooting community. The 1st edition of Pak Shooting Magazine is primarily focused on hardcore shooting related articles as well as preservation of wildlife and habitat management/ restoration through focused efforts including responsible hunting. To make this happen, number of volunteer community-based and volunteer organizations are already playing a part, however, the need of the time is to create awareness especially among hunting community as well as other stakeholders to promote responsible practices. Moreover, I am grateful to the shooters for their input/ contributions. I extend my special thanks to our dedicated editorial and graphics design team for making the 1st edition of this magazine possible. This idea could never had been accomplished alone, so I would like to thank the Patron in Chief and all of our contributors for their guidance and valuable suggestions. I am looking forward to a healthy and mutually beneficial participation of the shooting community in Pakistan to further refine upcoming issues of this magazine. Shahid Raza i ii C ntents Special Feature 1 Stalking Experience in Misgar (Northern Areas) An Unforgetable Experience The Spirit of MAJOSC 6 Step by Step Guide for Selecting your First Firearam 13 Introduction to F Class Shooting 21 2nd Muhammad Ali Jinnah Open Shooting Championship 25 Bringing the Wildlife Back from the Brink 31 Hunting Calibers Currently in Use in Pakistan 35 Fundamentals of Pistol Shooting 46 Habitat Conservation in Takatu Balochistan 52 Product Review (AK-12) 57 My 60 Years of Shikar Experience in Pakistan 63 Hunting Ethics and Regulations 70 Information given in the articles is the personal knowledge and views of the authors. -

Issues and Challenges to Academic Journalism and Mass Communication in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Volume 6 number 3 Journalism Education page 53 Issues and challenges to academic journalism and mass communication in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Sajjad Ali, University of Swat, KPK, Pakistan; Muhammad Shahid, University of Peshawar, Pakistan; Muhammad Saeed, The Islamia University of Bahawlpur, Pakistan; Muhammad Tariq, The Islamia University of Bahawlpur, Pakistan. Abstract Through this study, the researchers aim to explore the his- tory of Journalism and Mass Communication education in Pakistan in general and the evolution of academic disci- pline in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) in particular. The study also explores the problems and prospects of the Journal- ism and Mass Communication Departments in KPK. The re- searchers used qualitative method and collected the data though secondary resources as well as conducted in-depth interviews with the chairpersons and in-charge of the de- partments. The researchers developed five questions and six objectives to explore the history of academic journal- ism in KPK and highlight the problems of the concerned de- partments. The study disclosed that the academic Journal- ism and Mass Communication started as discipline in 1974 and presently there are seven departments in government universities and one in a private sector university. The Articles Page 54 Journalism Education Volume 6 number 3 study found out the answers of the designed questions and proved the objective that the departments of journal- ism and Mass Communication are facing academic, profes- sional, curricula, administrative, technical, lack of research culture, lack of coordination with other journalism depart- ments and media organizations, printing, broadcasting, telecasting, online journalism, practical journalism, educa- tion system, lack of research environment, administrative, technical and financial resources for the development of research journal publication. -

Afridi Tribe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Center on Contemporary Conflict Center for Contemporary Conflict (CCC) Publications 2016 Afridi Tribe Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/49867 Program for Culture and Conflict Studies AFRIDI TRIBE The Program for Culture & Conflict Studies Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, CA Material contained herein is made available for the purpose of peer review and discussion and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. PRIMARY LOCATION Khyber Agency, Peshawar District MAJOR TOWNS The headquarters for the Political Agent is in Peshawar, but Assistant Political Agents may be found in Bara, Jamrud, and Landi Kotal. There is also a government presence (Customs house) at Torkham on the Durand Line. TERRAIN AND CLIMATE TERRAIN FATA is situated between the latitudes of 31° and 35° North, and the longitudes of 69° 15' and 71° 50' East, stretching for maximum length of approximately 450 kilometers and spanning more than 250 kilometers at its widest point. Spread over a reported area of 27,220 square kilometers, it is bounded on the north by the district of Lower Dir in the NWFP, and on the east by the NWFP districts of Bannu, Charsadda, Dera Ismail Khan, Karak, Kohat, Lakki Marwat, Malakand, Nowshera and Peshawar. On the south-east, FATA joins the district of Dera Ghazi Khan in the Punjab province, while the Musa Khel and Zhob districts of Balochistan are situated to the south. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum Is a Rich Repository of the Unique Art Pieces of Gandhara Art in Stone, Stucco, Terracotta and Bronze

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Peshawar Museum is a rich repository of the unique art pieces of Gandhara Art in stone, stucco, terracotta and bronze. Among these relics, the Buddhist Stone Sculptures are the most extensive and the amazing ones to attract the attention of scholars and researchers. Thus, research was carried out on the Gandharan Stone Sculptures of the Peshawar Museum under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Ihsan Ali, the then Director of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP, currently Vice Chancellor Hazara University and Muhammad Naeem Qazi, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar. The Research team headed by the authors included Messrs. Syed Ayaz Ali Shah, Muhammad Ashfaq, Abdul Hameed Chitrali, Muhammad Zahir, Asad Raza, Shahid Khan, Muhammad Imran Khan, Asad Ali, Muhammad Haroon, Ubaidullah Afghani, Kaleem Jan, Adnan Ahmad, Farhana Waqar, Saima Afzal, Farkhanda Saeed and Ihsanullah Jan, who contributed directly or indirectly to the project. The hard working team with its coordinated efforts usefully assisted for completion of this research project and deserves admiration for their active collaboration during the period. It is great privilege to offer our sincere thanks to the staff of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums Govt. of NWFP, for their outright support, in the execution of this research conducted during 2002-06. Particular mention is made here of Mr. Saleh Muhammad Khan, the then Curator of the Peshawar Museum, currently Director of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP. The pioneering and relevant guidelines offered by the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Govt. of NWFP deserve appreciation for their technical support and ensuring the availability of relevant art pieces. -

A Case Study of Mahsud Tribe in South Waziristan Agency

RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY By MUHAMMAD IRFAN MAHSUD Ph.D. Scholar DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (SESSION 2011 – 2012) RELIGIOUS MILITANCY AND TRIBAL TRANSFORMATION IN PAKISTAN: A CASE STUDY OF MAHSUD TRIBE IN SOUTH WAZIRISTAN AGENCY Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE (December, 2018) DDeeddiiccaattiioonn I Dedicated this humble effort to my loving and the most caring Mother ABSTRACT The beginning of the 21st Century witnessed the rise of religious militancy in a more severe form exemplified by the traumatic incident of 9/11. While the phenomenon has troubled a significant part of the world, Pakistan is no exception in this regard. This research explores the role of the Mahsud tribe in the rise of the religious militancy in South Waziristan Agency (SWA). It further investigates the impact of militancy on the socio-cultural and political transformation of the Mahsuds. The study undertakes this research based on theories of religious militancy, borderland dynamics, ungoverned spaces and transformation. The findings suggest that the rise of religious militancy in SWA among the Mahsud tribes can be viewed as transformation of tribal revenge into an ideological conflict, triggered by flawed state policies. These policies included, disregard of local culture and traditions in perpetrating military intervention, banning of different militant groups from SWA and FATA simultaneously, which gave them the raison d‘etre to unite against the state and intensify violence and the issues resulting from poor state governance and control. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

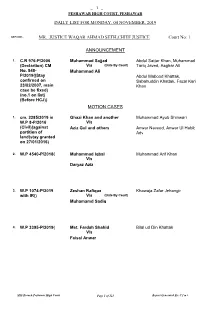

Single Bench List for 04-11-2019

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. C.R 976-P/2006 Muhammad Sajjad Abdul Sattar Khan, Muhammad (Declartion) CM V/s (Date By Court) Tariq Javed, Asghar Ali No. 848- Muhammad Ali P/2019((Stay Abdul Mabood Khattak, confirned on Sabahuddin Khattak, Fazal Karim 23/02/2007, main Khan case be fixed) (no.1 on list) (Before HCJ)) MOTION CASES 1. cm. 2285/2019 in Ghazi Khan and another Muhammad Ayub Shinwari W.P 8-P/2016 V/s (Civil)(against Aziz Gul and others Anwar Naveed, Anwar Ul Habib partition of Adv land(stay granted on 27/01/2016) 2. W.P 4540-P/2018() Muhammad Iqbal Muhammad Arif Khan V/s Daryaz Aziz 3. W.P 1074-P/2019 Zeshan Rafique Khawaja Zafar Jehangir with IR() V/s (Date By Court) Muhamamd Sadiq 4. W.P 3395-P/2019() Mst. Fardah Shahid Bilal ud Din Khattak V/s Faisal Anwar MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 121 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 5. W.P 4300-P/2019() Afzal Imran Ali Mohmand V/s Mst. Rashida i W.P 4716/2019 Mst Rashida Abid Ayub V/s Afzal 6. Cr.M(BCA) 3065- The State Waqas Khan Chamkani P/2019() V/s Noor Dad Khan 7. Cr.M(BCA) 3100- Muhammad Yousaf Syed Abdul Fayaz P/2019() V/s Abdullah Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 8.