The Great War and the European Avant-Garde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Futurism's Obsession with Speed in 1960S

Deus (ex) macchina: The Legacy of Futurism’s Obsession with Speed in 1960s Italy Adriana M. Baranello University of California, Los Angeles Il Futurismo si fonda sul completo rinnovamento della sensibilità umana avvenuto per effetto delle grandi scoperte scientifiche.1 In “Distruzione di sintassi; Imaginazione senza fili; Parole in lib- ertà” Marinetti echoes his call to arms that formally began with the “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” in 1909. Marinetti’s loud, attention grabbing, and at times violent agenda were to have a lasting impact on Italy. Not only does Marinetti’s ideology reecho throughout Futurism’s thirty-year lifespan, it reechoes throughout twentieth-century Italy. It is this lasting legacy, the marks that Marinetti left on Italy’s cultural subconscious, that I will examine in this paper. The cultural moment is the early Sixties, the height of Italy’s boom economico and a time of tremendous social shifts in Italy. This paper will look at two specific examples in which Marinetti’s social and aesthetic agenda, par- ticularly the nuova religione-morale della velocità, speed and the car as vital reinvigorating life forces.2 These obsessions were reflected and refocused half a century later, in sometimes subtly and sometimes surprisingly blatant ways. I will address, principally, Dino Risi’s 1962 film Il sorpasso, and Emilio Isgrò’s 1964 Poesia Volkswagen, two works from the height of the Boom. While the dash towards modernity began with the Futurists, the articulation of many of their ideas and projects would come to frui- tion in the Boom years. Leslie Paul Thiele writes that, “[b]reaking the chains of tradition, the Futurists assumed, would progressively liberate humankind, allowing it to claim its birthright as master of its world.”3 Futurism would not last to see this ideal realized, but parts of their agenda return continually, and especially in the post-war period. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity Matilde Marcolli 2015 • Mythopoesis: the capacity of the human mind to spontaneously generate symbols, myths, metaphors, ::: • Psychology (especially C.G. Jung) showed that the human mind (especially the uncon- scious) continuously generates a complex lan- guage of symbols and mythology (archetypes) • Religion: any form of belief that involves the supernatural • Mythopoesis does not require Religion: it can be symbolic, metaphoric, lyrical, visionary, without any reference to anything supernatural • Visionary Modernity has its roots in the Anarcho-Socialist mythology of Progress (late 19th early 20th century) and is the best known example of non-religious mythopoesis 1 Part 1: Futurist Trains 2 Trains as powerful symbol of Modernity: • the world suddenly becomes connected at a global scale, like never before • trains collectively drive humankind into the new modern epoch • connected to another powerful symbol: electricity • importance of the train symbolism in the anarcho-socialist philosophy of late 19th and early 20th century (Italian and Russian Futurism avant garde) 3 Rozanova, Composition with Train, 1910 4 Russolo, Dynamism of a Train, 1912 5 From a popular Italian song: Francesco Guccini \La Locomotiva" ... sembrava il treno anch'esso un mito di progesso lanciato sopra i continenti; e la locomotiva sembrava fosse un mostro strano che l'uomo dominava con il pensiero e con la mano: ruggendo si lasciava indietro distanze che sembravano infinite; sembrava avesse dentro un potere tremendo, la stessa forza della dinamite... ...the train itself looked like a myth of progress, launched over the continents; and the locomo- tive looked like a strange monster, that man could tame with thought and with the hand: roaring it would leave behind seemingly enor- mous distances; it seemed to contain an enor- mous might, the power of dynamite itself.. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, 1900-45 by Owen HEATHCOTE and DAVID Loose LEY, Lecturersinfrenchstudiesat the University Ofbradford

French Studies THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, 1900-45 By OwEN HEATHCOTE and DAVID LoosE LEY, LecturersinFrenchStudiesat the University ofBradford I. EssAYs, STUDIES Angles, Circumnavigations, posthumously reprints articles on, among others, Alain, Aragon, Claudel, Copeau, Drieu la Rochelle, Du Bos, Fernandez, Gide, Giono, Larbaud, Paulhan, Riviere, Supervielle, Valery. Shari Benstock, Women of the Left Bank: Paris, rgoo-1940, Austin, Texas U.P., 5I8 pp., is an original study which, though chiefly concerned with the lives and works of American expatriates (Colette is an exception), sheds light on the modernist culture of literary Paris by investigating the contribution of women to it and the specificity of their experience within it. Claudel Studies, I 3, no. 2, I I I pp., subtitled 'Satan, Devil, or Mephistopheles?', addresses the problem of evil conceived as existing independently of the individual: A. Espiau de la Maestre on Satan in Claudel's theatre, S. Maddux on Bernanos, M. M. Nagy on Valery, C. S. Brosman on Gide, L. M. Porter on Mauriac's Les Anges noirs, P. Brady on Proust and Des vignes, M.G. Rose on Green, and B. Stiglitz on Malraux. Hommage Dicaudin is a rich volume focusing on the birth of the modern and straddling I 9th and 20th cs. Of relevance to our period are the third section, 'de !'esprit nouveau', the fourth, devoted naturally to Apollinaire, and the fifth, 'derives de l'esprit nouveau', containing pieces on the unconscious in Soupault, and on Apollinaire andjouve. Others figuring here arejammes, Cendrars, Reverdy, and Aragon. Hommages Petit•contains inidits by Green, Claude!, and Mauriac and eight articles on C. -

Contents Preface Vii Acknowledgments Ix Part I

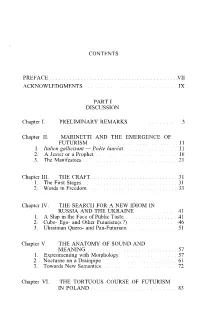

CONTENTS PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX PART I DISCUSSION Chapter I. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 3 Chapter II. MARINETTI AND THE EMERGENCE OF FUTURISM 11 1. Italien gallicisant — Poète lauréat 11 2. A Jester or a Prophet 16 3. The Manifestoes 21 Chapter III. THE CRAFT 31 1. The First Stages 31 2. Words in Freedom 33 Chapter IV. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW IDIOM IN RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE 41 1. A Slap in the Face of Public Taste 41 2. Cubo- Ego- and Other Futurism(s ?) 46 3. Ukrainian Quero- and Pan-Futurism 51 Chapter V. THE ANATOMY OF SOUND AND MEANING 57 1. Experimenting with Morphology 57 2. Nocturne on a Drainpipe 61 3. Towards New Semantics 72 Chapter VI. THE TORTUOUS COURSE OF FUTURISM IN POLAND 83 XII FUTURISM IN MODERN POETRY Chapter VII. THE FURTHER EXPANSION OF THE FUTURIST IDEAS 97 1. Futurism in Czech and Slovak Poetry 97 2. Slovenia 102 3. Spain and Portugal 107 4. Brazil 109 Chapter VIII. CONCLUSION 117 PART II A SELECTION OF FUTURIST POETRY I. ITALY 125 A. FREE VERSE 125 Libero Altomare Canto futurista 126 A Futurist Song 127 A un aviatore 130 To an Aviator 131 Enrico Cardile Ode alia violenza 134 Ode to Violence 135 Enrico Cavacchioli Fuga in aeroplano 142 Flight in an Aeroplane 143 Auro D'Alba II piccolo re 146 The Little King 147 Luciano Folgore L'Elettricità 150 Electricity 151 F.T. Marinetti À l'automobile de course 154 To a Racing Car 155 Armando Mazza A Venezia 158 To Venice 159 Aldo Palazzeschi E lasciatemi divertire 164 And Let Me Have Fun 165 B. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

![Free Art As the Basis of Life: Harmony and Dissonance (On Life, Death, Etc.) [Extracts], 1908](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3227/free-art-as-the-basis-of-life-harmony-and-dissonance-on-life-death-etc-extracts-1908-763227.webp)

Free Art As the Basis of Life: Harmony and Dissonance (On Life, Death, Etc.) [Extracts], 1908

The works of genius and mediocrity—the latter are justified because they have historic interest. The painting of those who have long since decayed (who they were is forgotten, a riddle, a mystery)—how you upset the nineteenth century. Until the 1830s, the age of Catherine was enticing, alluring, and delightful: pre- cise and classical. Savage vulgarization. The horrors of the Wanderers—general deterio- ration—the vanishing aristocratic order—hooligans of the palette a la Ma- kovsky 1 and Aivazovsky,2 etc. Slow development, new ideals—passions and terrible mistakes! Sincejhg first exhibition of the World of Art, in 1899, there has beenja.. new era. Aitigtg lnoK ft? fresh wind.blows away Repin's chaffy spirit, the bast shoe of the Wanderers loses its apparent strength. But it's not Serov, not Levitan, not Vrubel's 3 vain attempts at genius, not the literary Diaghilevans, but the Blue Rose, those who have grouped around The Golden Flee ce and later the Russian imptv^jpnist^ niirhireH on Western mCSels, those who trembled at the sight of Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cezanne _ (the synthesis of French trends in painting)—these are the hopes for the rebirth of Russian painting. " ""— NIKOLAI KULBIN Free Art as the Basis of Life: Harmony and Dissonance (On Life, Death, etc.) [Extracts], 1908 Born St. Petersburg, 1868; died St. Petersburg, 1917. Professor at the St. Petersburg Military Academy and doctor to the General Staff; taught himself painting; IQO8: organized the Impressionist groupj lecturer and theoretician; 1909: group broke up, dissident members contributing to the founding of the Union of Youth, opened for- mally in February 1910; 1910 on: peripheral contact with the Union of Youth; close to the Burliuks, Vladimir Markov, Olga Rozanova; ca. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

Écrits Sur Bergson

Écrits sur Bergson 1890 Georges Lechalas. “Le Nombre et le temps dans leur rapport avec l’espace, à propos de Les Données immédiates. ” Annales de Philosophie Chrétienne, N.S. 23 (1890): 516-40. Print. Eng. trans. “Number and Time in Relation to Space, as Concerns Time and Free Will .” 1893 Maurice Blondel. L’action. Essai d’une critique de la vie et d’une science de la pratique . Paris: Alcan, 1893, 495. (Bibliographie de Philosophie Contemporaine) Eng. trans. Action . This item is republished in 1950, Presses Universitaires de France. 1894 Jean Weber. “Une étude réaliste de l’acte et ses conséquences morales.” Revue de métaphysique et de morale . 2.6, 1894, 331-62. Eng. trans. “A Realist Study of the Act and its Moral Consequences.” 1897 Gustave Belot. “Un Nouveau Spiritualisme.” Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Etranger , 44.8 (August 1897): 183-99. The author sees a danger of materialism in Matter and Memory. Print. Eng. trans. “A New Spiritualism.” Victor Delbos. “Matière et mémoire, étude critique.” Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale , 5 (1897): 353- 89. Print. Eng. trans. “ Matter and Memory , A Critical Study.” Frédéric Rauh. “La Conscience du devenir.” Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale , 4 (1897): 659-81; 5 (1898): 38-60. Print. Eng. trans. “The Awareness of Becoming.” L. William Stern. “Die psychische Präsenzzeit.” Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane 13 (1897): 326-49. The author strongly criticizes the concept of the point-like present moment. Print. Eng. trans. “The Psychological Present.” 1901 Émile Boutroux. “Letter to Xavier Léon. July 26, 1901” in Lettere a Xavier Léon e ad altri. -

Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald De Andrade

Modernist Poetics between France and Brazil: Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald de Andrade Sarah Lazur Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 1 © 2019 Sarah Lazur All rights reserved 2 ABSTRACT Modernist Poetics between France and Brazil: Influence and Cannibalism in the Works of Blaise Cendrars and Oswald de Andrade Sarah Lazur This dissertation examines the collegial and collaborative relationship between the Swiss-French writer Blaise Cendrars and the Brazilian writer Oswald de Andrade in the 1920s as an exemplar of shifting literary influence in the international modernist moment and examines how each writer’s later accounts of the modernist period diminished the other’s influential role, in revisionist histories that shaped later scholarship. In analyzing a broad range of source texts, published poems, fiction and essays as well as personal correspondence and preparatory materials, I identify several areas of likely mutual influence or literary cannibalism that defied contemporaneous expectations for literary production from European cultural capitals or from the global south. I argue that these expectations are reinforced by historical circumstances, including political and economic crises and cultural nationalism, and by tracing the changes in the authors’ accounts, I give a fuller narrative that is lacking in studies approaching either of the authors in a monolingual context. 3 Table of Contents Abbreviations ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – Foreign Paris 20 Chapter 2 – Primitivisms and Modernity 57 Chapter 3 – Collaboration and Cannibalism 83 Chapter 4 – Un vaste malentendu 121 Conclusion 166 Bibliography 170 i Abbreviations ABBC A Aventura Brasileira de Blaise Cendrars: Eulalio and Calil’s major anthology of articles, correspondence, essays, by all major participants in Brazilian modernism who interacted with Cendrars. -

Biblioteca Di Studi Di Filologia Moderna – 37 –

BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI DI FILOLOGIA MODERNA – 37 – DIPARTIMENTO DI LINGUE, LETTERATURE E STUDI INTERCULTURALI Università degli Studi di Firenze Coordinamento editoriale Fabrizia Baldissera, Fiorenzo Fantaccini, Ilaria Moschini Donatella Pallotti, Ernestina Pellegrini, Beatrice Töttössy BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI DI FILOLOGIA MODERNA Collana Open Access del Dipartimento di Lingue, Letterature e Studi Interculturali Direttore Beatrice Töttössy Comitato scientifico internazionale Enza Biagini (Professore Emerito), Nicholas Brownlees, Martha Canfield, Richard Allen Cave (Emeritus Professor, Royal Holloway, University of London), Piero Ceccucci, Massimo Ciaravolo (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia), John Denton, Anna Dolfi, Mario Domenichelli (Professore Emerito), Maria Teresa Fancelli (Professore Emerito), Massimo Fanfani, Fiorenzo Fantaccini (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Paul Geyer (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn), Ingrid Hennemann, Sergej Akimovich Kibal’nik (Institute of Russian Literature [the Pushkin House], Russian Academy of Sciences; Saint-Petersburg State University), Ferenc Kiefer (Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; Academia Europaea), Michela Landi, Murathan Mungan (scrittore), Stefania Pavan, Peter Por (CNRS Parigi), Gaetano Prampolini, Paola Pugliatti, Miguel Rojas Mix (Centro Extremeño de Estudios y Cooperación Iberoamericanos), Giampaolo Salvi (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest), Ayşe Saraçgil, Rita Svandrlik, Angela Tarantino (Università degli Studi di Roma ‘La Sapienza’), Maria