Movement‐Based Influence: Resource Mobilization, Intense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Vita Futurista

ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΗΜΙΟ ΘΕΑΛΙΑ ΦΟΛΗ ΕΠΙΣΗΜΩΝ ΣΟΤ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΟΤ ΣΜΗΜΑ ΙΣΟΡΙΑ, ΑΡΦΑΙΟΛΟΓΙΑ ΚΑΙ ΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΚΗ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΟΛΟΓΙΑ Γιάννης Πέτκος Vita Futurista Γενεαλογίες του φουτουριστικού ο κινητισμού στον 19 αιώνα Διπλωματική εργασία Μεταπτυχιακό Πρόγραμμα Σπουδών «Διεπιστημονικές Προσεγγίσεις στις Ιστορικές, Αρχαιολογικές και Ανθρωπολογικές Σπουδές» Επόπτες Καθηγητές Επίκ. Καθ.: Μήτσος Μπιλάλης Επίκ. Καθ.: Ιωάννα Λαλιώτου Βόλος 2015 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 Σ’ αυτούς που τολμούν να ονειρευτούν και ν’ αποτύχουν 1 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 2 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 Ζ άκεζε απηνπαξαηήξεζε απέρεη πνιχ απφ ην λα καο νδεγεί ζηελ απηνγλσζία: ρξεηαδφκαζηε ηελ ηζηνξία δηφηη ην παξειζφλ ζπλερίδεη λα θπιά κέζα καο κε εθαηφ θχκαηα. Φ. Νίηζε 3 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 4 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 Περιεχόμενα Ευχαριστίες 7 Ένας κόσμος σε κίνηση 9 Προβληματική της κίνησης 17 Μοντέρνα αντίληψη: μια κινούμενη εικόνα 23 Περπατώντας (και καυγαδίζοντας) στο Παρίσι 28 Από τις οπτικές ψευδαισθήσεις στην 4η διάσταση 40 Cinématism 58 Υουτουριστική σύνοψη 83 Εξομολογητική αποφώνηση υπό τη μορφή συλλογής 85 απομνημονευμάτων Πηγές εικόνων 87 Βιβλιογραφία 93 Υιλμογραφία 105 5 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 6 Institutional Repository - Library & Information Centre - University of Thessaly 10/01/2018 01:46:45 EET - 137.108.70.7 Ευχαριστίες Αλ αξρίζσ λα ςάρλσ απαξρέο απφ δσ, ζα πξέπεη πξψηα λα επραξηζηήζσ ηνπο κεγάινπο επεξγέηεο ηεο δσήο κνπ: ηε κεηέξα κνπ, ηνπο Metallica θαη ηνλ Νίηζε. -

URBAN ISLANDS Vol 1

Urban Island (n): a post industrial site devoid of program or inhabitants; a blind spot in the contemporary city; an iconic ruin; dormant infrastructure awaiting cultural inhabitation. ii iii iv v vi CUTTINGS URBAN ISLANDS vol 1 EDITED BY JOANNE JAKOVICH Copyright URBAN ISLANDS vol 1 : CUTTINGS Published by SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library www.sup.usyd.edu.au © 2006 Urban Islands Project: Joanne Jakovich , Olivia Hyde, Thomas Rivard © of individual chapters is retained by the contributors Editor: Joanne Jakovich [email protected] Preface: GEOFF BAILEY Assistant Editors: Jennifer Gamble, Jane HYDE layout: Joanne Jakovich photography: kota arai Cover Design: Olivia Hyde Cover Photo: Samantha Hanna PART III Design: Nguyen Khang Tran (Sam) URBAN ISLANDS PROJECT WWW.URBANISLANDS.INFO I NAUGURAL URBAN ISLANDS STUDIO , REVIEW + SYMPOSIUM ORGANISED BY : OLIVIA HYDE, THOMAS RIVARD, JOANNE JAKOV ICH & I NGO KUMIC, AUGUST 2006 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes : Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may b e reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University viii Copyright Press at the address b elow: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] ISBN 1–920898–55–7 Individual papers are available electronically through the Sydney e-Scholarship Repository at: ses.library.usyd.edu.au Printed in Australia at the University Publishing Service, University of Sydney. ix PREFACE Describing Cockatoo Island as a post-industrial site is a little like examining a Joseph Cornell box and not noticing its contents. -

The City Rises and the Futurist City

The City Rises and the Futurist City ROSS JENNER University of Auckland Despite its offering littleactual technical information (what is being built cannot even bededuced) and few cluesas to locality otherthan the new metropolitan reality that rises from the violent industrialisation and urbanisation ofthe outskirts (the reality that dominates the Futurist poetic), Boccioni's painting,Tlle Cig Rises, nevertheless, offers key glimpses into Futurist thinking about architecture. The building site depicted is more than a setting of work, it is a setting to work, the building of a site. Boccioni strains towards a future through an image of labor and traffic that sets to work every molecule within the confines of the canvas. The figures and animals strain to pull components but are themselves pulled into a swirling world of force lines that leaves no detached viewpoint or frame. The site of the future is being built. Totally immersed in urban life the city was the source of Futurist inspiration. In that it condensed and produced a new reality from it, Futurism was the first avant garde movement directly toconfront the problematic of urban development and make the city the privileged site of modernity. klarinetti eulogised this city in his Founding Fig. 1. Boccioni The City Rues (La citti che sale), 1909-10. Manifesto of I C)W: We will sing of great croads excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; ue will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we mill sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and -

The Legacy of Antonio Sant'elia: an Analysis of Sant'elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism During the Fascist Era

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2014 The Legacy of Antonio Sant'Elia: An Analysis of Sant'Elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism during the Fascist Era Ashley Gardini San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Gardini, Ashley, "The Legacy of Antonio Sant'Elia: An Analysis of Sant'Elia's Posthumous Role in the Development of Italian Futurism during the Fascist Era" (2014). Master's Theses. 4414. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.vezv-6nq2 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4414 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LEGACY OF ANTONIO SANT’ELIA: AN ANALYSIS OF SANT’ELIA’S POSTHUMOUS ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF ITALIAN FUTURISM DURING THE FASCIST ERA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Art and Art History San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Ashley Gardini May 2014 © 2014 Ashley Gardini ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled THE LEGACY OF ANTONIO SANT’ELIA: AN ANALYSIS OF SANT’ELIA’S POSTHUMOUS ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF ITALIAN FUTURISM DURING THE FASCIST ERA by Ashley Gardini APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ART AND ART HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2014 Dr. -

A Century of Futurist Architecture: from Theory to Reality

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 27 December 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201812.0322.v1 A century of Futurist Architecture: From Theory to Reality Farhan Asim Venu Shree M.Arch Student (Sustainable Architecture) Assistant Professor NIT Hamirpur, India NIT Hamirpur, India +91-8948318668 +91-7018620827 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract— The Italian Architect Antonio Sant’Elia is considered the father of Futurist Architecture, the one who envisioned the future II. FUTURISTIC ARCHITECTURE: IDEAS, ORIGIN & FATE of cities on the basis of the native population’s work culture and habitual traits. It has been a century since his ideas were introduced The new generation of futurists hypothesized about in his ‘L-Architettura Futurista - Manifesto’ and later circulated by the vision for new metropolises and megalopolis with F.T. Marinetti, today they are making a prodigious impact on the flexible and more useful urban environments. The Avant- architecture style of the entire world. His revolutionary ideas Garde ideas of futurists stayed as an inherent part of modern percolated through the murky aftermath of 19th & 20th century art movements. His out-worldly pre-modernist principles gave rise to the architectural edification. The futurist idea of development notion of exclusive habitats for generations and started the post-war was to disregard history and come up with new ideologies trend of housing typologies as an industrialized and fast track and structure that could formulate the future cities and medium -

Pre-Bauhaus Europe Table of Contents

Pre-Bauhaus Europe Table of Contents Understanding the Bauhaus 1 Modernism 2 Formalism and Expressionism 2 Post Impressionism 3 Fauvism 5 Die Brucke 5 Der Blaue Reiter 6 Cubism 6 Analytic Cubism 8 Synthetic Cubism 9 Response to Cubism 11 Towards Abstraction 11 Italian Futurism 11 Russian Response 12 Rayonism 12 Supermatism 12 Constructivism 13 Architecture 15 Art Nouveau 15 Early Modernist 16 Impact of World War I 16 De Stijl 16 French Purism 18 The Metaphysical School 18 Dada 19 Intersecting Paths 20 Pre-Bauhaus Europe Theo understand pre-Bauhaus Europe, one must first understand Bauhaus and the pholophy behind it. The “House of Building,” or Bauhaus, was the creation of Walter Gropius (1883-1969) during 1919 to 1933. Gropius was an admirer of the Bauhutten, the medieval building guilds of Germany, and wished to resurrect them through the union of modern art and industry. In a time of innumerable transformations Gropius wished to unite the efforts of architects, artists and designers into what he called “cultural synthesis.” The Bauhaus The Bauhaus was born in 1919 after Gropius was permitted to combine the schools of art and craft in Weimar, Germany. Ordinary craftsmen as well as famous artists such as Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky were hired to teach. Gropius felt that an understanding of materials, which was taught in workshops that included metalwork, carpentry, interior design, construction, and furniture making, must be mastered before architecture. His goal was to create: “A clear, organic architecture, whose inner logic will be radiant and naked, unencumbered by lying facades and trickeries; we want an architecture adapted to our world of machines, radios and fast motor cars, and architecture whose function is clearly recognizable in the relation of its forms” (Stokstad 1081). -

Iakov Chernikhov and His Time

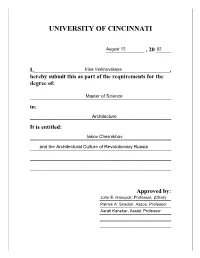

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ IAKOV CHERNIKHOV AND THE ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE OF REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the college of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2002 by Irina Verkhovskaya Diploma in Architecture, Moscow Architectural Institute, Moscow, Russia 1999 Committee: John E. Hancock, Professor, M.Arch, Committee Chair Patrick A. Snadon, Associate Professor, Ph.D. Aarati Kanekar, Assistant Professor, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The subject of this research is the Constructivist movement that appeared in Soviet Russia in the 1920s. I will pursue the investigation by analyzing the work of the architect Iakov Chernikhov. About fifty public and industrial developments were built according to his designs during the 1920s and 1930s -

Italian Futurism 1909–1944 Reconstructing the Universe February 21–September 1, 2014 Italian Futurism 1909–1944 Reconstructing the Universe

ITALIAN FUTURISM 1909–1944 RECONSTRUCTING THE UNIVERSE FEBRUARY 21–SEPTEMBER 1, 2014 ITALIAN FUTURISM 1909–1944 RECONSTRUCTING THE UNIVERSE Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit A NOTE TO TEACHERS Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe is the first comprehensive overview of Italian Futurism to be presented in the United States. This multidisciplinary exhibition examines the historical sweep of Futurism, one of Europe’s most important twentieth-century avant-garde movements. This Resource Unit focuses on several of the disciplines that Futurists explored and provides techniques for connecting with both the visual arts and other areas of the curriculum. This guide is also available on the museum’s website at www.guggenheim.org/artscurriculum with images that can be downloaded or projected for classroom use. The images may be used for education purposes only and are not licensed for commercial applications of any kind. Before bringing your class to the Guggenheim, we invite you to visit the exhibition and/or the exhibition website, read the guide, and decide which aspects of the exhibition are most relevant to your students. For more information and to schedule a visit for your class, please call 212 423 3637. This curriculum guide is made possible by The Robert Lehman Foundation. This exhibition is made possible by Support is provided in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and the David Berg Foundation, with additional funding from the Juliet Lea Hillman Simonds Foundation and the New York State Council on the Arts. The Leadership Committee for Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe is also gratefully acknowledged for its generosity, including the Hansjörg Wyss Charitable Endowment; Stefano and Carole Acunto; Giancarla and Luciano Berti; Ginevra Caltagirone; Massimo and Sonia Cirulli Archive; Daniela Memmo d’Amelio; Achim Moeller, Moeller Fine Art; Pellegrini Legacy Trust; and Alberto and Gioietta Vitale. -

ELCS6005: Raging Broom of Madness: Futurism and Modernity | University College London

09/30/21 ELCS6005: Raging Broom of Madness: Futurism and Modernity | University College London ELCS6005: Raging Broom of Madness: View Online Futurism and Modernity Not all books listed are in the UCL Library. You may need to use the library at the Estorick Gallery or the Art History Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum. I can issue students letters for these institutions on request. Altshuler B, ‘Chapter 2 Cubism Meets the Public’, The avant-garde in exhibition: new art in the 20th century (Harry N Abrams 1994) ——, ‘Chapter 5 The Last Futurist Exhibition, Petrograd, December 1915-January 1916’, The avant-garde in exhibition: new art in the 20th century (Harry N Abrams 1994) ——, ‘Les Peintres Futuristes Italiens, Paris, 1912’, Salon to biennial: exhibitions that made art history : 1863-1959 (Phaidon 2008) Antliff M and Leighten PD, Cubism and Culture, vol World of art (Thames & Hudson 2001) Antonello PP, ‘Beyond Futurism: Bruno Munari’s “Useless Machines”’, Futurism and the technological imagination, vol Avant garde critical studies (Rodopi 2009) Apollinaire G, ‘L’anti-Tradition Futuriste’, Marinetti e i futuristi, vol Strumenti di studio (1 ed, Garzanti 1994) Apollonio U, Futurist Manifestos, vol [The world of art library ; modern movements] (Thames and Hudson 1973) Balla G and others, Balla, Depero: Ricostruzione Futurista Dell’universo (Fonte d’Abisso edizioni 1989) Balla G and Depero F, ‘Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe’, Futurist manifestos, vol [The world of art library ; modern movements] (Thames and Hudson 1915) Banham -

A Bonfire of Vanities: Futurism and the Second Reformation

A Bonfire of Vanities: Futurism and the Second Reformation Why do so few books on twentieth century art history pay attention to futurism? Or to put it differently, why do so many books pay so little attention to futurism? Possibly because it was a short-lived movement, dying with the deaths of two of its main practitioners and theorists in WWI; possibly because the spokesperson who did not die became affiliated with Mussolini and so there has been a tendency to associate futurism with a type of pre-fascist mind-set, possibly because in the eyes of some critics and historians it appears to be derivative of cubism with nothing new to offer. If we go against the grain and decide to include futurism, what reasons do we have for doing this? Possibly because of the ways in which futurism is precisely unlike cubism: although cubism did not eliminate the real world from its content and Picasso did use his art as a form of social commentary, this moderately political use of his art has always been elusive and hard to perceive. In contrast, the futurists centralized the social-political thematic to such a degree, we have to see this movement as being a social revolution before being an aesthetic one. Umberto Boccioni: Development of a Bottle in Development of a Bottle (from a slightly different Space, 1912 angle) A cmparison between these two works may illuminate the differences between the movements and foreground the futurist experience. The Bottle has been cut open and the forms have been peeled off and juxtaposed in such a way that the viewer cannot logically put them together. -

Milka Bliznakov the City of the Russian Futurists

MILKA BLIZNAKOV THE CITY OF THE RUSSIAN FUTURISTS "We look at their nothingness from the heights of skyscrapers! ..." A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, December, 1912 Futurist architecture and urbanism transcend the confining categories and fixed time periods of their artistic counterparts. Although Futurism was an international phenomenon, only one architect, Antonio Sant' Elia (1888- 1916) aligned himself with the Futurists. Sant' Elia was a latecomer to the movement and the "Manifesto of Futurist Architecture" was the last prin- cipal Futurist manifesto to be published (July, 1914). Hence, Filippo Tom- maso Marinetti (1876-1944), the founder of Italian Futurism, did not have an architect among his followers when he visited Russia at the beginning of 1914 (January 26 to February 15). Thus, Sant' Elia's architectural manifesto was not among those published in Russian translations during 1914 and, in fact, was never translated into Russian. Furthermore, no Russian architect, plan- ner, or urban designer called himself a Futurist, and none joined the Futurist groups such as Hylaea or Centrifuge which, in any case, were founded by po- ets, painters, and composers. The works of the members of these groups, however, their proclamations and theoretical premises, their social and aes- thetic commitments, had a lasting impact on the development of avant- garde architecture and city planning. The aim of this study is to demonstrate that the architects borrowed the legacy of the artists and carried its develop- ment further, well after Futurism in the arts had declined. One may even con- clude that the only logical expansion of Futurism, Suprematism, and Con- structivism is to be found in architecture and urban design.