It's Time to Modernize the Office Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

If It's Broke, Fix It: Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule Of

If it’s Broke, Fix it Restoring Federal Government Ethics and Rule of Law Edited by Norman Eisen The editor and authors of this report are deeply grateful to several indi- viduals who were indispensable in its research and production. Colby Galliher is a Project and Research Assistant in the Governance Studies program of the Brookings Institution. Maya Gros and Kate Tandberg both worked as Interns in the Governance Studies program at Brookings. All three of them conducted essential fact-checking and proofreading of the text, standardized the citations, and managed the report’s production by coordinating with the authors and editor. IF IT’S BROKE, FIX IT 1 Table of Contents Editor’s Note: A New Day Dawns ................................................................................. 3 By Norman Eisen Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 President Trump’s Profiteering .................................................................................. 10 By Virginia Canter Conflicts of Interest ............................................................................................... 12 By Walter Shaub Mandatory Divestitures ...................................................................................... 12 Blind-Managed Accounts .................................................................................... 12 Notification of Divestitures .................................................................................. 13 Discretionary Trusts -

Annual Report 2017

fa What is CAPI? Corruption costs taxpayers trillions of dollars a year worldwide that could be better spent on social, health, education, and other programs to improve the lives of citizens worldwide. Despite the pervasiveness of corruption, finding, stopping and preventing it is daunting. There are anti-corruption offices in place across the country and globe, but the system overall is relatively young and largely decentralized. Individual corruption-fighting offices are often disparate and adrift, unconnected to peers and experts in other jurisdictions. These offices face common challenges and can benefit greatly from active collaboration and shared best practices. In 2013, the New York City Department of Investigation partnered with Columbia Law School to create the Center for the Advancement of Public Integrity (CAPI). Over the past nearly five years, CAPI has grown into a platform through which public integrity professionals can connect with each other and provides the resources to help them succeed. Executive Director Jennifer Rodgers CAPI is a nonprofit resource center dedicated to bolstering anti-corruption research, promoting key tools and best practices, and cultivating a professional network to share new developments and lessons learned, both online and through live events. Unique in its municipal focus, CAPI’s work emphasizes practical lessons and practitioner needs. Through this network, in which anti-corruption practitioners and agencies can share their insights, methods, and successes, CAPI seeks to support the fight against corruption in all its forms. We strive to create an environment where members of our community learn from one another to better promote public integrity and good governance. -

Office of Government Ethics (OGE) Emails Containing the Word Goya, 2020

Description of document: Office of Government Ethics (OGE) Emails containing the word Goya, 2020 Requested date: 15-17-July-2020 Release date: 29-December-2020 Posted date: 11-January-2021 Source of document: FOIA request OGE FOIA Officer Office of Government Ethics Suite 500 1201 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20005-3917 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. UNITED STATES OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT ETHICS * December 29, 2020 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL ONLY Tracking No: OGE FOIA FY 20/061 & OGE FOIA FY 20/062 This is in response to your Freedom oflnformation Act (FOIA) requests, which were received by the OGE FOIA Office on July 15, 2020 and July 17, 2020. -

13 Policy Areas Critical to an Effective, Ethical, and Accountable Government

REPORT THE BAKER’S DOZEN: 13 Policy Areas Critical to an Effective, Ethical, and Accountable Government February 18, 2021 Acknowledgements EDITOR Liz Hempowicz CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Katherine Hawkins Dylan Hedtler-Gaudette Rebecca Jones Jake Laperruque Sean Moulton Mandy Smithberger Timothy Stretton Sarah Turberville ADVISORS Scott Amey Danielle Brian COPY-EDITING AND FACT-CHECKING Danni Downing Neil Gordon Mia Steinle DESIGN Leslie Garvey THE PROJECT ON GOVERNMENT OVERSIGHT (POGO) is a nonpartisan independent watchdog that investigates and exposes waste, corruption, abuse of power, and when the government fails to serve the public or silences those who report wrongdoing. 1100 G Street NW, Suite 500 We champion reforms to achieve a more effective, Washington, DC 20005 ethical, and accountable federal government that WWW.POGO.ORG safeguards constitutional principles. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 5 Promoting Accountability When Government Officials Commit Wrongdoing ............. 7 ▌ Recommendations for Legislative Action ....................................................... 11 ▌ Recommendations for Executive Action ......................................................... 14 Promoting an Executive Branch Ethics Framework that Protects the Public Interest ........................................................................................................... 15 ▌ Recommendations for Legislative Action ....................................................... -

Experts Say Conway May Have Broken Ethics Rule by Touting Ivanka Trump'

From: Tyler Countie To: Contact OGE Subject: Violation of Government Ethics Question Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 11:26:19 AM Hello, I was wondering if the following tweet would constitute a violation of US Government ethics: https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/829356871848951809 How can the President of the United States put pressure on a company for no longer selling his daughter's things? In text it says: Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump My daughter Ivanka has been treated so unfairly by @Nordstrom. She is a great person -- always pushing me to do the right thing! Terrible! 10:51am · 8 Feb 2017 · Twitter for iPhone Have a good day, Tyler From: Russell R. To: Contact OGE Subject: Trump"s message to Nordstrom Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:03:26 PM What exactly does your office do if it's not investigating ethics issues? Did you even see Trump's Tweet about Nordstrom (in regards to his DAUGHTER'S clothing line)? Not to be rude, but the president seems to have more conflicts of interest than someone who has a lot of conflicts of interests. Yeah, our GREAT leader worrying about his daughters CLOTHING LINE being dropped, while people are dying from other issues not being addressed all over the country. Maybe she should go into politics so she can complain for herself since government officials can do that. How about at least doing your jobs, instead of not?!?!? Ridiculous!!!!!!!!!!!! I guess it's just easier to do nothing, huh? Sincerely, Russell R. From: Mike Ahlquist To: Contact OGE Cc: Mike Ahlquist Subject: White House Ethics Date: Wednesday, February 08, 2017 1:23:01 PM Is it Ethical and or Legal for the Executive Branch to be conducting Family Business through Government channels. -

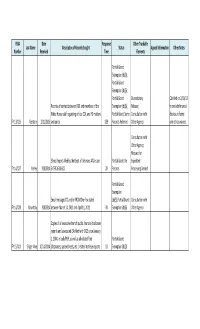

FOIA Number Last Name Date Received Description of Records

FOIA Date Response Other Trackable Last Name Description of Records Sought Status Appeal Information Other Notes Number Received Time Elements Partial Grant: Exemption (b)(3); Partial Grant: Exemption (b)(5); Partial Grant: Discretionary Clarified on 2/19/13 Records of contact between OGE and members of the Exemption (b)(6); Release; to exclude financial White House staff regarding ethics, COI, and FD matters Partial Grant: Some Consultation with disclosure forms FY 13/023 Gerstein 2/11/2013 and policy 559 Records Referred Other Agency and ethics waivers. Consultation with Other Agency; Request for Ethics Reports filed by the Dept. of Veterans Affairs per Partial Grant: No Expedited FY 14/027 Kelley 9/8/2014 5 CFR 2638.602 20 Records Processing Denied Partial Grant: Exemption Email messages TO and/or FROM Don Fox dated (b)(5);Partial Grant: Consultation with FY 14/028 Ravnitzky 9/8/2014 between March 14, 2011 and April 11, 2011 30 Exemption (b)(6) Other Agency Copies of all executive branch public financial disclosure reports and associated EAs filed with OGE since January 1, 2004, in bulk/PDF, as well as all related filed Partial Grant: FY 15/001 Singer‐Vine 10/14/2014 (databases, spreadsheets, etc.) related to these reports 18 Exemption (b)(3) Possible Frequent Request; Request List of correspondences between the OGE and for Expedited members of Congress and their offices from Jan. 2007 Processing ‐ Granted FY 15/002 Lowande 10/16/2014 to Jan. 2014 8 Full Grant (No adjudication) Finanial disclosure statement year 2006‐ 2014 of Judge Clarence Copper and Judge Richard W. -

The Trump Adminis- Tration’S Oversight of the Trump Inter- National Hotel Lease

LANDLORD AND TENANT: THE TRUMP ADMINIS- TRATION’S OVERSIGHT OF THE TRUMP INTER- NATIONAL HOTEL LEASE (116–33) HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, PUBLIC BUILDINGS, AND EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 25, 2019 Printed for the use of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure ( Available online at: https://www.govinfo.gov/committee/house-transportation?path=/ browsecommittee/chamber/house/committee/transportation U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 41–130 PDF WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:50 Sep 14, 2020 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 P:\HEARINGS\116\ED\9-25-2~1\TRANSC~1\41130.TXT JEAN TRANSPC154 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon, Chair ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, SAM GRAVES, Missouri District of Columbia DON YOUNG, Alaska EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas ERIC A. ‘‘RICK’’ CRAWFORD, Arkansas ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland BOB GIBBS, Ohio RICK LARSEN, Washington DANIEL WEBSTER, Florida GRACE F. NAPOLITANO, California THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina STEVE COHEN, Tennessee SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey RODNEY DAVIS, Illinois JOHN GARAMENDI, California ROB WOODALL, Georgia HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia JOHN KATKO, New York ANDRE´ CARSON, Indiana BRIAN BABIN, Texas DINA TITUS, Nevada GARRET GRAVES, Louisiana SEAN PATRICK MALONEY, New York DAVID ROUZER, North Carolina JARED HUFFMAN, California MIKE BOST, Illinois JULIA BROWNLEY, California RANDY K. WEBER, SR., Texas FREDERICA S. WILSON, Florida DOUG LAMALFA, California DONALD M. PAYNE, JR., New Jersey BRUCE WESTERMAN, Arkansas ALAN S. -

May 4, 2018 the Honorable Trey Gowdy Chairman Committee On

May 4, 2018 The Honorable Trey Gowdy Chairman Committee on Oversight and Government Reform U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 Dear Mr. Chairman: This week, President Donald Trump and his attorney, Rudy Giuliani, made a stunning revelation—Donald Trump, while serving as the sitting President, personally “funneled” money through his attorney, Michael Cohen, disguised as a “retainer” for legal services they admit were never provided, to reimburse a secret payment of $130,000 to Stephanie Clifford, the adult film star known as Stormy Daniels, in exchange for her silence before the election. As a preliminary matter, this revelation appears to directly contradict President Trump’s statements on Air Force One on April 5, 2018, that he knew nothing about this payment.1 Although President Trump and Mr. Giuliani appear to be arguing against potential prosecution for illegal campaign donations, they have now opened up an entirely new legal concern—that the President may have violated federal law when he concealed the payment to Ms. Clifford and his reimbursements for this payment by omitting them from his annual financial disclosure form. Congress passed the Ethics in Government Act in 1978 to require federal officials to publicly disclose financial liabilities that could affect their decision-making on behalf of the American people. The applicable disclosure requirements “include a full and complete statement with respect to ... [t]he identity and category of value of the total liabilities owed to any creditor ... which exceed $10,000 at any time during the preceding calendar year.”2 The Office of Government Ethics, the federal office charged with implementing and overseeing this law, has issued regulations that require federal officials to disclose any liability over $10,000 “owed to any creditor at any time during the reporting period,” as well as the 1 Trump Says He Didn’t Know About Stormy Daniels Payment, CNN (Apr. -

Nominations of Gilbert B. Kaplan, Matthew Bassett, and Robert Charrow

S. HRG. 115–290 NOMINATIONS OF GILBERT B. KAPLAN, MATTHEW BASSETT, AND ROBERT CHARROW HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE NOMINATIONS OF GILBERT B. KAPLAN, TO BE UNDER SECRETARY FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE, DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE; MATTHEW BASSETT, TO BE AS- SISTANT SECRETARY FOR LEGISLATION, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES; AND ROBERT CHARROW, TO BE GENERAL COUNSEL, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES AUGUST 3, 2017 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Finance U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–926—PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 15:32 Aug 01, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 R:\DOCS\30926.000 TIM COMMITTEE ON FINANCE ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa RON WYDEN, Oregon MIKE CRAPO, Idaho DEBBIE STABENOW, Michigan PAT ROBERTS, Kansas MARIA CANTWELL, Washington MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN CORNYN, Texas ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey JOHN THUNE, South Dakota THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia SHERROD BROWN, Ohio ROB PORTMAN, Ohio MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania DEAN HELLER, Nevada MARK R. WARNER, Virginia TIM SCOTT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri BILL CASSIDY, Louisiana CHRIS CAMPBELL, Staff Director JOSHUA SHEINKMAN, Democratic Staff Director (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 15:32 Aug 01, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 R:\DOCS\30926.000 TIM C O N T E N T S OPENING STATEMENTS Page Hatch, Hon. -

Office of Government Ethics FOIA Request Log, FY 2017

Office of Government Ethics FOIA request log, FY 2017 Brought to you by AltGov2 www.altgov2.org/FOIALand FY17 FOIA Log ‐ Current through 10/1/17 Descriptions do not always contain the exact request language APPEAL APPEAL APPEAL Request Description of Days Initially Days Exemption(s) Number Records Sought Allowed Received Perfected Completed Tolled Disposition Applied Other Date Received Date Closed Disposition All Appointment Calendars for the Director of the OGE for the years 2014, 2015 16/086 and 2016 to date. 30 9/28/2016 9/28/2016 11/10/2016 Partial Grant/Partial Denial (b)(6) Correspondence exchanged between OGE personnel and representatives of presidential candidates Trump & Clinton, 8/1/2016 17/001 to present 20 10/3/2016 10/3/2016 10/18/2016 Partial Grant/Partial Denial (b)(5), (b)(6) A copy of the Freedom of Information Act APPEALS Log for the Office of Government Ethics for the 17/002 time period since 2006. 20 10/31/2016 10/31/2016 11/4/2016 Partial Grant/Partial Denial (b)(6) October 29, 2016 complaint against FBI 17/003 Director. 20 10/31/2016 10/31/2016 11/30/2016 Partial Grant/Partial Denial (b)(6) All personal financial disclosure reports filed by Antonio Weiss, counselor 17/004 to the Treasury Secretary. 20 11/7/2016 11/7/2016 11/7/2016 Full Denial Based on Exemptions (b)(3) Records referred by State Dept. in response to request for emails between Cheryl Mills and 17/005 various individuals. 20 11/7/2016 11/7/2016 11/29/2016 Partial Grant/Partial Denial (b)(3), (b)(6) Internal OGE FOIA 17/006 procedures guide. -

Anuary 18, 2017 10:25:59 AM Attachments: OGE Form 278E Excel Ver.Xls FOIA

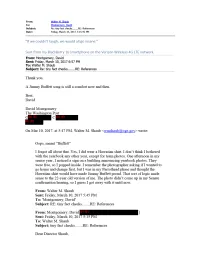

From: David J. Apol To: Heather A. Jones; Deborah J. Bortot (b)(3) 278e Cc: Elaine Newton reports are not Subject: FW: Draft SF-278 for Jared Kushner available through Date: Wednesday, January 18, 2017 10:25:59 AM Attachments: OGE Form 278e Excel ver.xls FOIA Anything you want me to add to this before I send? (b)(5) draft language of a proposed email re CD request Nonresponsive email from outside OGE Nonresponsive email from outside OGE Brandon A. Steele From: Deborah J. Bortot Sent: Wednesday, January 18, 2017 10:41 AM To: David J. Apol; Heather A. Jones Cc: Elaine Newton Subject: RE: Draft SF-278 for Jared Kushner Dave, Once we get the request, there will be additional questions. Thanks, Deb From: David J. Apol Sent: Wednesday, January 18, 2017 10:26 AM To: Heather A. Jones; Deborah J. Bortot Cc: Elaine Newton Subject: FW: Draft SF-278 for Jared Kushner Anything you want me to add to this before I send? UNITED STATES OFFICE OF GOVERNMENT ETHICS * JAN 2 6 2017 Stefan C. Passantino Deputy Counsel to the President The White House Office Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. Passantino: In response to your request of January 25, 2017, enclosed are Certificates of Divestiture OGE-2017-002 for Jared C. Kushner, Senior Advisor to the President, White House Office; OGE-2017-003 for lvanka Trump as trustee for the lvanka Trump Revocable Trust; OGE-2017-004 for dependent minor child of Jared C. Kushner; OGE-2017-005 for ependent minor child of Jared C. Kushner; and OGE-2017-006 for dependent minor child of Jared C. -

Responsive Records

Just checking a few things. *I noticed in the JMU yearbook that most of the young men have suits and ties for their senior photos, but it appears as though you went with a Hawaiian shirt. As a flash of personality, I thought I would mention it in passing. I forgot all about that. Yes, I did wear a Hawaiian shirt. I don’t think I bothered with the yearbook any other year, except for team photos. One afternoon in my senior year, I noticed a sign on a building announcing yearbook photos. They were free, so I popped inside. I remember the photographer asking if I wanted to go home and change first, but I was in my Parrothead phase and thought the Hawaiian shirt would have made Jimmy Buffet proud. That sort of logic made sense to the 22-year old version of me. The photo didn’t come up in my Senate confirmation hearing, so I guess I got away with it until now. *On your Form 278e, I noticed the everyman detail that you are still paying a student loan, which I thought I would mention, without saying the amount or other detail. It’s a publicly available form, so that’s not a secret. *Is it correct that your five-year term is up in January 2018 (as opposed to some other month?) Yes. The last day of the term is January 8, 2018. (Not sure if that should be written as “ends on January 8” or “ends after January 8”) Thank you. Best, david David Montgomery The Washington Post w (b) (6) c(b) (6) (b) (6) From: Walter M.