Technical Developments Among Mberi Blacksmiths, the Nya Division, Logone Oriental Region (CHAD)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paper Submitted for Presentation at UNU-WIDER’S Conference, Held in Maputo on 5-6 July 2017

DRAFT WIDER Development Conference Public economics for development 5-6 July 2017 | Maputo, Mozambique This is a draft version of a conference paper submitted for presentation at UNU-WIDER’s conference, held in Maputo on 5-6 July 2017. This is not a formal publication of UNU-WIDER and may refl ect work-in-progress. THIS DRAFT IS NOT TO BE CITED, QUOTED OR ATTRIBUTED WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM AUTHOR(S). The impact of oil exploitation on wellbeing in Chad Abstract This study assesses the impact of oil revenues on wellbeing in Chad. Data used come from the two last Chad Household Consumption and Informal Sector Surveys ECOSIT 2 & 3 conducted in 2003 and 2011 by the National Institute of Statistics and Demographic Studies. A synthetic index of multidimensional wellbeing (MDW) is first estimated using a multiple components analysis based on a large set of welfare indicators. The Difference-in-Difference approach is then employed to assess the impact of oil revenues on the average MDW at departmental level. Results show that departments receiving intense oil transfers increased their MDW about 35% more than those disadvantaged by the oil revenues redistribution policy. Also, the farther a department is from the capital city N’Djamena, the lower its average MDW. Economic inclusion may be better promoted in Chad if oil revenues fit local development needs and are effectively directed to the poorest departments. Keys words: Poverty, Multidimensional wellbeing, Oil exploitation, Chad, Redistribution policy. JEL Codes: I32, D63, O13, O15 Authors Gadom -

Assistance Pour Un Mois

Impact COVID-19 2ème niveau Population Total population 3ème niveau administratif Population totale en Assistance pour un mois administratif totale en Phase en insécurité Phase 2 3 à 5 grand centre alimentaire Céréales huile (bidon sucre Niébé rural urbains (tonne) de 20 litre) (tonne) (tonne) Batha Batha Est 58 380 18 575 7 805 26 380 11 676 7 805 220 4 397 110 44 Batha Batha Ouest 87 276 61 093 11 668 72 761 17 455 11 668 606 12 127 303 121 Batha Fitri 40 613 9 747 5 430 15 177 8 123 5 430 126 2 529 63 25 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Nord 29 142 24 589 3 896 28 485 5 828 3 896 237 4 747 119 47 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Ouest 27 847 19 891 3 723 23 614 5 569 3 723 197 3 936 98 39 Barh El Gazal Bahr El Gazal Sud 74 851 60 297 10 007 70 304 14 970 10 007 586 11 717 293 117 Borkou Borkou Yala 9 275 8 533 1 240 9 773 1 855 1 240 81 1 629 41 16 Borkou Borkou 45 271 28 169 6 052 34 221 9 054 6 052 285 5 703 143 57 Chari-Baguirmi Baguirmi 49 375 0 6 601 6 601 9 875 6 601 55 1 100 28 11 Chari-Baguirmi Chari 24 222 0 3 238 3 238 4 844 3 238 27 540 13 5 Chari-Baguirmi Loug-Chari 32 807 0 4 386 4 386 6 561 4 386 37 731 18 7 Guera Guera 50 749 30 449 6 785 37 234 10 150 6 785 310 6 206 155 62 Guera Abtouyour 64 050 41 879 8 563 50 442 12 810 8 563 420 8 407 210 84 Guera Mangalmé 25 137 13 965 3 361 17 326 5 027 3 361 144 2 888 72 29 Guera Barh Signaka 30 480 15 240 4 075 19 315 6 096 4 075 161 3 219 80 32 Hajer Lamis Dababa 63 866 20 168 8 538 28 706 12 773 8 538 239 4 784 120 48 Hajer Lamis Dagana 60 971 16 629 8 151 24 780 12 194 8 151 206 4 -

République Du Tchad

Enquête Nationale Post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des Ménages Ruraux du Tchad République du Tchad Février 2012 Données de novembre/décembre 2011 Enquête Nationale post-récoltes sur la Sécurité Alimentaire des ménages ruraux du Tchad Pour plus d’informations, contacter : Bureau de pays du PAM Tchad Unité VAM/M&E, Section Programme : [email protected] Anne-Claire Mouilliez, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] Wilfred Nkwambi, Bureau du PAM Tchad: [email protected] © Programme Alimentaire Mondial, Service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM), février 2012 Programme alimentaire mondial des Nations Unies (PAM) Siège social : Via C.G. Viola 68, Parco de Medici, 00148, Rome, Italie Toutes les informations sur le service de l’Analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire (VAM) et les rapports en format électronique sur http://www.wfp.org/food-security ou [email protected] 2 Table des matières LISTE DES TABLEAUX ................................................................................................................................................ 6 LISTE DES FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... 6 LISTE DES CARTES ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 LISTE DES ANNEXES .................................................................................................................................................. -

Chapter 1 Present Situation of Chad's Water Development and Management

1 CONTEXT AND DEMOGRAPHY 2 With 7.8 million inhabitants in 2002, spread over an area of 1 284 000 km , Chad is the 25th largest 1 ECOSI survey, 95-96. country in Africa in terms of population and the 5th in terms of total surface area. Chad is one of “Human poverty index”: the poorest countries in the world, with a GNP/inh/year of USD 2200 and 54% of the population proportion of households 1 that cannot financially living below the world poverty threshold . Chad was ranked 155th out of 162 countries in 2001 meet their own needs in according to the UNDP human development index. terms of essential food and other commodities. The mean life expectancy at birth is 45.2 years. For 1000 live births, the infant mortality rate is 118 This is in fact rather a and that for children under 5, 198. In spite of a difficult situation, the trend in these three health “monetary poverty index” as in reality basic indicators appears to have been improving slightly over the past 30 years (in 1970-1975, they were hydraulic infrastructure respectively 39 years, 149/1000 and 252/1000)2. for drinking water (an unquestionably essential In contrast, with an annual population growth rate of nearly 2.5% and insufficient growth in agricultural requirement) is still production, the trend in terms of nutrition (both quantitatively and qualitatively) has been a constant insufficient for 77% of concern. It was believed that 38% of the population suffered from malnutrition in 1996. Only 13 the population of Chad. -

Tchad: Situations De Conflits, Inondations Et Ennemis Des Cultures Mise À Jour Du 9 Octobre 2017

Tchad: situations de conflits, inondations et ennemis des cultures Mise à jour du 9 octobre 2017 Légendes Tibesti Ouest TIBESTI Inondations Tibesti Est Conflits éleveurs Oiseaux granivores Chenilles légionnaires Fada ENNEDI OUEST Am-Djarass Borkou Yala ENNEDI EST 7 oct. à Koundjourou BORKOU (Dpt de Batha Ouest) Destruction des Borkou cultures par les Mourtcha oiseaux granivores à 14.000 ha envahies, Wadi Hawar 6.241,8 t détruites et Nord Kanem Kobé 4.964 ménages KANEM WADI FIRA Mégri touchés Biltine Barh-El-Gazel Nord 7 oct. Dar-Tama Batha Ouest à Ouaddi Faman Kanem BARH-EL-GAZEL Fouli (18.108 habitants) BATHA Batha Est Barh-El-Gazel Sud Ouara Assoungha dans la sous- Kaya LAC Wadi Bissam OUADDAÏ Wayi Barh-El-Gazel Ouest préfecture d’Arada Mamdi (Dpt de Biltine). Dagana Abdi Fitri Conflits ente HADJER-LAMIS Mangalmé Haraze-Al-Biar éleveurs 4 oct. N’Djamena Dababa Djourf Al Ahmar N'Djaména Guéra SILA 3 morts. Invasion de champ Abtouyour dans la banlieue de N'DJAMENA Kimiti Chari Baguirmi et du champ de GUÉRA Aboudéia maïs de l’ITRAD par CHARI-BAGUIRMI Inondations: Bahr-Azoum les chenilles Mayo-Lemié Barh-Signaka Salamat: Barh Azoum: env. 388,5 ha SALAMAT légionnaires détruites Loug-Chari Mayo-Boneye Mandoul: Mandoul Oriental: 42 villages, MAYO-KEBBI EST 1.445 personnes touchées, 1.453 ha. Pas Mayo-Binder Mont Illi Haraze-Mangueigne de données sur le Mandoul Oriental et Lac Léré Lac Iro Kabbia Tandjilé Est Bahr-Köh Barh Sara affectés aussi MAYO-KEBBI OUEST Tandjile OuestTANDJILÉ MOYEN-CHARI Tandjilé Centre Logone Oriental: Dpt de Nya Pende: Mayo-Dallah Mandoul Oriental Guéni Ngourkosso La Pendé 465 ha détruites – pas de ménages Lac Wey Dodjé MANDOUL touchés estimés La NyaMandoul Occidental LOGONE OCCIDENTAL Grande Sido Kouh Est Nya, Kouh-Est, Pende: pas de données LOGONE ORIENTAL Barh-Sara Kouh Ouest sur les personnes et superficies Monts de Lam La Nya Pendé Affectées Moyen Chari: Grande Sido: env. -

Chad Food Security Update: July, 2000 Summary 1

Chad Food Security Update: July, 2000 Summary The month of July was characterized by a satisfactory situation overall, in both the Sudanian and Sahelian zones of Chad. Highly food insecure populations in the Sahelian zone constituted an important exception. People there had to intensify their income-generating activities (such as working for others and selling cattle) in order to buy their basic food staples. The agricultural season is underway, although it started late this year in most cantons compared to last year. Pasture conditions are good in the Sudanian zone while the Sahelian zone only started greening up during the third dekad (10-day period) of July. Livestock health is also good. Millet and sorghum prices remain affordable, although higher than prices last year in the Sahelian zone. Prices in Kanem and parts of Ouaddaï Prefectures in the Sahelian zone increased during the past quarter, though this is normal for the pre-harvest period. 1. Agrometeorological Situation The Inter-topical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) oscillates between 17º N and 19º N, between the cities of Fada and Ounianga Kebir (Borkou and Ennedi Sub-prefectures). Large quantities of rainfall were recorded south of the ITCZ during the third dekad of July, notably in the Sahelian zone. According to the Directorate of Water Resources and Meteorology (DREM), total dekadal rainfall during July was less than the rainfall during the same period last year, except for several rain stations. Rainfall during the third dekad exceeded long-term average levels (1961-1990) in most locations. Satellite images analyzed by FEWS NET/Chad corroborate rain station data showing that third dekad rainfall varied between average and very good in the Sahel and Sudanian zones. -

Caractéristiques Du Pays Et Méthodologie De L'enquête

CARACTÉRISTIQUES DU PAYS ET MÉTHODOLOGIE DE L’ENQUÊTE 1 Bandoumal Ouagadjio 1.1 CARACTÉRISTIQUES DU PAYS 1.1.1 Géographie et climat Le Tchad est situé entre les 7e et 24e degrés de latitude Nord et les 13e et 24e degrés de longitude Est. Il couvre une superficie de 1 284 000 km2 ; il est le cinquième pays le plus vaste d’Afrique après le Soudan, l’Algérie, le Zaïre et la Libye. Du Nord au Sud, il s’étend sur 1 700 km et, de l’Est à l’Ouest, sur 1 000 km. Il partage ses frontières avec, au Nord, la Libye, à l’Est, le Soudan, au Sud, la République Centrafricaine et, à l’Ouest, le Cameroun, le Nigeria et le Niger. De par sa position géographique, au Sud du Tropique du Cancer et au cœur du continent africain, le Tchad est marqué par une continentalité accentuée dont l’étranglement économique est l’une des conséquences. En effet, le pays est dépourvu de toute façade maritime. Le port le plus proche est Port Harcourt (Nigéria), à 1 700 km de N’Djaména. Cet enclavement extérieur est accentué par une insuffisance des réseaux routiers qui rend difficile la circulation durant une bonne partie de l’année. Le pays appartient politiquement et économiquement à l’Afrique Centrale, mais en raison des similitudes des conditions climatiques, il est rattaché également aux pays sahéliens. Sur le plan climatique, on distingue trois zones principales : • la zone saharienne qui couvre environ 50 % de la superficie du pays et qui comprend les régions du BET, le nord de la région du Kanem et une partie de la région du Batha. -

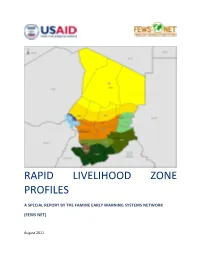

Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad

RAPID LIVELIHOOD ZONE PROFILES A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 The Uses of the Profiles ............................................................................................................................ 4 Key Concepts ............................................................................................................................................. 5 What is in a Livelihood Profile .................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad ....................................................................................................... 9 National Overview .................................................................................................................................... 9 Zone 1: South cereals and cash crops ..................................................................................................... 13 Zone 2: Southwest Rice Dominant ......................................................................................................... -

June 1988 Vulnerability Assessment

FEWS Country Report JUNE 1988 CHAD VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM Produced by the Office of Technical Resources - Africa Bureau - USAID FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM The Famine Early Warning System (FEWS) is ax, Agency-wide effort coordinated by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)'s Africa Bureau. Its mission is to assemble, analyze and report on the complex conditions which may ead to famine in any one of the following drought-prone countries in Africa: e Burkina * Chad a Ethiopia a Mali o Mauritania * Mozambique a Niger * Sudan FEWS reflects the Africa Bureau's commitment to providing relia!-e and timely information to decision-makers within the Agency, within the eight countries, and among the broader donor community, so that they can take appropriate actions to avert a famine. FEWS relies on information it obtains from a wide variety of sources including: USAID Missions, host governments, pAvate voluntary organizations, international donor and relief agencies, and the remote sensing and academic communities. In addition, the FEWS system obtains information directly from FEWS Field Representatives currently assigned to six USAID Missions. FEWS analyzes the information it collects, crosschecks and analyzes the data, and systematically disseminates its findings through the following publicaticns: " FEWS Country Reports -produced monthly during the growing season, and bimonthly during the rest of the year (for more information on FEWS publications turn to the back inside cover of this report); ar-d " FEWS Bulletins -produced every ten days duing the growing season. In addition, FEWS serves the USAID staff by. * preparing FEWS Alert Memoranda for distribution to top USAID dexision-makers when dictated by fast-breaking events; * preparing Sp-clal Reports, maps, briefings, analyses, etc. -

Situation in Numbers UNICEF Appeal 2021 US$ 59.5 Million

Chad Humanitarian Situation Report No. 01, 2021 Photo credit: UNICEF /2020/Ndah-lah Situation in Numbers Reporting Period: 1 January to 31 March 2021 3,100,000 children in need of humanitarian assistance Highlights • During the reporting period, 57,526 malnourished children were admitted and treated in the supported health centres with a cure rate of 94.6 per cent. 6,400,000 people in need • 3,245 children had access to psychosocial support sessions, in child -friendly (revised OCHA HRP 2020) spaces in the provinces of Lac, Borkou Ouaddai and Guera. • 9,740 people (5,064 women and 4,676 men) in need had access to 401,090 appropriately designed and managed latrines in the province of Lac, Salamat, under 5 children with SAM Logone Occidental and Mandoul (OCHA HNO 2021) • 253,214 people were reached with COVID-19 prevention measures through 236,426 a partnership with 12 community radios and community relays in the internally displaced people provinces of Mayo Kebbi Est, Mayo Kebbi Ouest, Tandjile, Logone (revised OCHA HRP 2020) Occidental, Logone Oriental, Mandoul and Lac. • 7,290 crisis-affected children have been provided with access to education through distance learning in the provinces of Lac, Mandoul and Moyen Chari. UNICEF’s Response (as of March 2021) UNICEF Appeal 2021 US$ 59.5 million SAM admissions 20% Funding Status (in US$) Nutrition Measles vaccination 14% Health Funds received, Carry- Safe water access 0% $4M WASH forward, $9.8M MHPSS access 11% Child Protection 3-17 years boys and girls affected by the 30% Funding crisis receive school materials gap, Education $45.7M PLWHIV on ART 3% HIV/AIDS Non-Food Items 3% Emergency 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% Humanitarian Action for Children: Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF is requesting US$ 59.5 million to meet the emergency needs of nearly 1.1 million vulnerable children and women in Chad in 2021. -

Provinces Du Logone Occidental Et Du Logone Oriental Mars 2021

TCHAD Provinces du Logone Occidental et du Logone Oriental Mars 2021 15°30'0"E 16°0'0"E 16°30'0"E 17°0'0"E 17°30'0"E Louagi Bero Mola Zabogo Garbian Mangse Dabgue Ngolo Gaberi Manai II Gouri Mankoulade Birboti Mahim Damala Gadjimbati Mahim II Zabogo Mongli Mangse Bembok Mangse Guidari Kihangala Dabgue Mbassa Kaselem Kelo Tchagra TANDJILÉ CENTRE Tamian Ngolo Midjar Ourouni Kablade Mindi-Lati Kahinga Toki M A Y O - K E B B I E S T Marbelem Lamge Kaselem Guessa Moussoum Koukwala KABBIA Bero Ndigou Bero Mangassou Manga Barmin Marbelem Kokro Gueni Tandjile Delimdi Melpongo Tedjere Koumabodan Bemangara Bemia Tchedoum Kaga Mbassa Dono-Manga Bebala Kokarti Goli Golt Ngara Kasselem Baimon Kaselem Mbaymou Guissa Kila Kolmade Tsia Mandjir Mouroum Touloum Tcher Dono Manga Mahim III Kouroukoutou Guediti Marbelem Pindjing Lao Boulmanddje Zagoni Gergendeng Mere Mogolo Tchagra Darandje Tamion Mbassa Kara Doa Babrou Maingone Bidakiro Nantissa Nantissa Kalite Kokarti Maita Maitate Dangara Mere Sibge Pa Bako Be Moula Koli Ngangara Broum Langue Nangda Banangourou Bodo Kakrai Marbelem Mogolo Dale Baoul Saoudji Djindra Bayam Babelo Beli Kouara Grabe Kariadeboum Kaga Palpaye Mbo Karoayan Bambo Magnia Kakoyo Koukar Yamb Maloum Kongermi Delbian Bouroumti Samango Ndilati Dobo Nangda Balkomia Berem Mbasa Disoua Gaidro Manga Balbal Kagde Bilma Tchaouen Ba Kaliin Belimdi Be Doumo Mokolo Kembati Karoya Dilati Mbakassa Yamba Tchangsou Tchagra Meretchinde Dogobara Kademane Kombotou Mbaya Delbian Kaidolo Kouara Gambaye Mointoro Kaga Tetelngar Nangasou Kali Bodo Mandal -

The Impact of the Oil Revenues Redistribution Policy

____________________ Région et Développement n° 44-2016 _________________ CROSS-COUNTY POVERTY COMPARISONS IN CHAD: THE IMPACT OF THE OIL REVENUES REDISTRIBUTION POLICY Gadom DJAL-GADOM* Armand MBOUTCHOUANG KOUNTCHOU** Abstract - This paper analyses the determinants of cross-county poverty dispar- ities in Chad within the context of oil exploitation. Data is provided from the last Chad Household Consumption and Informal Sector Survey (ECOSIT 3) and from the College for Control and Monitoring of Oil Revenues (CCSRP). The incidence of poverty is separately estimated for two groups of counties, accord- ing to the amount of oil revenues received with respect to their demographic weights. The difference between the poverty estimates is decomposed into char- acteristics and coefficients effects following the generalization of Oaxaca-type decomposition for poverty analysis. Results highlight the existence of a highly significant poverty disparity between the two groups of counties. The county- group with a relatively low share of oil revenues has a higher poverty rate than the other group. The effect of county characteristics explains 78.3% of this dif- ference in poverty, while 21.7% is explained by the return effect due to the dif- ferential impact of the characteristics over counties. It is expected that to better promote economic inclusion in Chad, the oil revenues redistribution policy should fit the specific local development needs. Keywords - CHAD, POVERTY INCIDENCE, LOCAL DISPARITIES, OIL EXPLOITATION, OAXACA DECOMPOSITION, DELTA METHOD JEL Classification - C20, D63, I30, O13, Q32 We wish to express our deep appreciation to the African Economic Research Consorti- um (AERC) for their financial support. We are also grateful to the resource persons and members of AERC’s thematic group A for various comments and suggestions that helped this study to undergo completion since its inception.