Strata Vol1 JORDAN BIRENBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRISM::Advent3b2 8.25

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 39th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 39e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Monday, April 3, 2006 Le lundi 3 avril 2006 11:00 a.m. 11 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 39th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Ms. Audrey première session de la 39e législature, pour l'expédition des O'Brien, Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. Marc Bosc, Deputy affaires. Mme Audrey O'Brien, greffière de la Chambre des Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. R. R. Walsh, Law Clerk and communes, M. Marc Bosc, sous-greffier de la Chambre des Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons, and Ms. Marie- communes, M. R. R. Walsh, légiste et conseiller parlementaire de Andrée Lajoie, Clerk Assistant of the House of Commons, la Chambre des communes, et Mme Marie-Andrée Lajoie, greffier Commissioners appointed per dedimus potestatem for the adjoint de la Chambre des communes, commissaires nommés en purpose of administering the oath to Members of the House of vertu d'une ordonnance, dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter Commons, attending according to their duty, Ms. Audrey O'Brien serment aux députés de la Chambre des communes, sont présents laid upon the Table a list of the Members returned to serve in this dans l'exercice de leurs fonctions. Mme Audrey O'Brien dépose sur Parliament received by her as Clerk of the House of Commons le Bureau la liste des députés qui ont été proclamés élus au from and certified under the hand of Mr. -

Torture of Afghan Detainees Canada’S Alleged Complicity and the Need for a Public Inquiry

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives | Rideau Institute on International Affairs September 2015 Torture of Afghan Detainees Canada’s Alleged Complicity and the Need for a Public Inquiry Omar Sabry www.policyalternatives.ca RESEARCH ANALYSIS SOLUTIONS About the Author Omar Sabry is a human rights researcher and ad- vocate based in Ottawa. He has previously worked in the Office of the Co-Investigating Judges at the United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Tri- als, for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Lebanon, and for Human Rights Watch in Egypt. He holds a Master of Arts in International Politics (with a focus on International Law) from the University of Ottawa, and a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy from the University of Toronto. ISBN 978-1-77125-231-7 Acknowledgements This report is available free of charge at www. policyalternatives.ca. Printed copies may be or- Peggy Mason, President of the Rideau Institute; dered through the CCPA National Office for $10. Paul Champ, lawyer at Champ & Associates; and Alex Neve, Secretary General of Amnesty Interna- PleAse mAke A donAtIon... tional Canada, provided feedback in the produc- Help us to continue to offer our tion of this report. Meera Chander and Fawaz Fakim, publications free online. interns at the Rideau Institute, provided research assistance. Maude Downey and Janet Shorten pro- With your support we can continue to produce high vided editing assistance. quality research — and make sure it gets into the hands of citizens, journalists, policy makers and progres- sive organizations. Visit www.policyalternatives.ca or call 613-563-1341 for more information. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

The Bloc Québécois As a Party in Parliament a Thesis Submitted To

A New Approach to the Study of a New Party: The Bloc Québécois as a Party in Parliament A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Arts In the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By James Cairns September 2003 Copyright James Cairns, 2003. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Graduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professors who supervised my thesis work, or in their absence, by the Head of the Department of Political Studies or the Dean of the College of Graduate Studies and Research. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii ABSTRACT Since forming a parliamentary party in 1994, the Bloc Québécois has been interpreted exclusively as the formal federal manifestation of the Québec separatist movement. -

Printable PDF Version

For enquiries, please contact: Public Enquiries Unit Elections Canada 257 Slater Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0M6 Tel.: 1-800-463-6868 Fax: 1-888-524-1444 (toll-free) TTY: 1-800-361-8935 www.elections.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Elections Canada Report of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada following the September 17, 2007, by-elections held in Outremont, Roberval–Lac-Saint-Jean and Saint-Hyacinthe–Bagot Text in English and French on inverted pages. Title on added t.p.: Rapport du directeur général des élections du Canada sur les élections partielles tenues le 17 septembre 2007 dans Outremont, Roberval–Lac-Saint-Jean et Saint-Hyacinthe–Bagot. ISBN: 978-0-662-05433-7 Cat. No.: SE1-2/2007-2 1. Canada. Parliament — Elections, 2007. 2. Elections — Quebec (province). I. Title. II. Title: Rapport du directeur général des élections du Canada sur les élections partielles tenues le 17 septembre 2007 dans Outremont, Roberval–Lac-Saint-Jean et Saint-Hyacinthe–Bagot. JL193.E43 2008 324.971’07309714 2008980067-2E © Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, 2008 All rights reserved Printed in Canada March 31, 2008 The Honourable Peter Milliken Speaker of the House of Commons Centre Block House of Commons Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 Dear Mr. Speaker: I have the honour to submit this report, which covers the administration of the by-elections held on September 17, 2007, in the electoral districts of Outremont, Roberval–Lac-Saint-Jean and Saint-Hyacinthe–Bagot. I have prepared the report in accordance with subsection 534(2) of the Canada Elections Act (S.C. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline. -

Martine Tremblay, La Rébellion Tranquille. Une Histoire Du Bloc Québécois (1990-2011), Montréal, Québec/Amérique, 2015, 631 P

Document generated on 09/29/2021 11:48 p.m. Bulletin d'histoire politique Martine Tremblay, La rébellion tranquille. Une histoire du Bloc québécois (1990-2011), Montréal, Québec/Amérique, 2015, 631 p. Réjean Pelletier Des marges et des normes : réflexions et témoignages sur la carrière de Jean-Marie Fecteau (1949-2012) Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2016 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1037425ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1037425ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Association québécoise d'histoire politique VLB éditeur ISSN 1201-0421 (print) 1929-7653 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Pelletier, R. (2016). Review of [Martine Tremblay, La rébellion tranquille. Une histoire du Bloc québécois (1990-2011), Montréal, Québec/Amérique, 2015, 631 p.] Bulletin d'histoire politique, 25(1), 198–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1037425ar Tous droits réservés © Association québécoise d'histoire politique et VLB This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Éditeur, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Martine Tremblay, La rébellion tranquille. Une histoire du Bloc québécois (1990-2011), Montréal, Québec/ Amérique, 2015, 631 p. Réjean Pelletier Université Laval Le Bloc québécois a été un acteur important de la scène politique fédérale durant vingt ans. -

Caucus & Critic

CAUCUS &CRITIC RESPONSIBILITIES / 69 CAUCUS &CRITIC RESPONSIBILITIES Ed Komarnicki, Parliamentary Secretary....32 FINANCE A complete list of caucus and critic Liberal Conservative Party responsibilities at the federal level. Omar Alghabra, Critic.................................34 Diane Ablonczy, Parliamentary Secretary ..30 For each area of responsibility, lists New Democratic Party Jim Flaherty, Minister .................................36 the appropriate Liberal, Olivia Chow, Deputy Critic.........................35 Liberal Conservative, Bloc Québécois, and Bill Siksay, Critic ........................................29 John McCallum, Critic ................................38 New Democratic Party Members of New Democratic Party Parliament. Turn to the page DEMOCRATIC REFORM indicated for complete Judy Wasylycia-Leis, Critic ........................33 information on a particular MP. Conservative Party Tom Lukiwski, Parliamentary Secretary.....32 FISHERIES AND OCEANS Rob Nicholson, Minister responsible for ....38 Bloc Québécois AGRICULTURE AND AGRI-FOOD Peter Van Loan, Minister ............................40 Jean-Yves Roy, Critic..................................45 Bloc Québécois Liberal Conservative Party Louis Plamondon, Critic..............................45 Stephen Owen, Critic ..................................29 Loyola Hearn, Minister ...............................48 Conservative Party Randy Kamp, Parliamentary Secretary .......29 Jacques Gourde, Parliamentary Secretary ...43 DEPUTY LEADER Liberal Christian Paradis, Secretary of -

Monday, October 5, 1998

CANADA VOLUME 135 S NUMBER 132 S 1st SESSION S 36th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, October 5, 1998 Speaker: The Honourable Gilbert Parent CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire'' at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 8729 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, October 5, 1998 The House met at 11 a.m. told that unanimous consent by the House and the NDP would be forthcoming only if the motion were not votable. _______________ The Deputy Speaker: Is there unanimous consent of the House Prayers that the opposition motion tabled with the Journals Branch on Friday, October 2, 1998 by Mr. Brien, the hon. member for _______________ Témiscamingue, be debated today under Business of Supply, Government Orders? D (1105) [English] [Translation] Mr. Bill Blaikie: Mr. Speaker, with the understanding that it is POINTS OF ORDER not votable. OPPOSITION MOTION The Deputy Speaker: The motion that I proposed to the House was only that it be debated, not that it be votable. Is that agreed? Mr. Michel Gauthier (Roberval, BQ): Mr. Speaker, I would Some hon. members: Agreed. like to seek the unanimous consent of the House that the opposition motion tabled with the Journals Branch on Friday, October 2, 1998 _____________________________________________ by Mr. Brien, the hon. member for Témiscamingue, be debated today under Business of Supply, Government Orders. [English] PRIVATE MEMBERS’ BUSINESS Mr. Bill Blaikie (Winnipeg—Transcona, NDP): Mr. Speaker, I [English] rise on a point of order. I understand that this motion is necessary because the motion was not in on time. -

Core 1..31 Journal (PRISM::Advent3b2 7.00)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 38th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 38e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 4 No 4 Thursday, October 7, 2004 Le jeudi 7 octobre 2004 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEES OF THE WHOLE VICE-PRÉSIDENT DES COMITÉS PLÉNIERS Pursuant to Order made Tuesday, October 5, 2004, the Speaker Conformément à l’ordre adopté le mardi 5 octobre 2004, le proposed that Mr. Proulx (Hull—Aylmer) be the candidate for the Président propose que M. Proulx (Hull—Aylmer) soit le candidat position of Deputy Chair of Committees of the Whole. au poste de vice-président des comités pléniers. Accordingly, the motion “That Mr. Proulx (Hull—Aylmer) be En conséquence, la motion « Que M. Proulx (Hull—Aylmer) appointed Deputy Chair of Committees of the Whole” was deemed soit nommé vice-président des comités pléniers » est réputée to have been moved and seconded. proposée et appuyée. The question was put on the motion and it was agreed to. La motion, mise aux voix, est agréée. ASSISTANT DEPUTY CHAIR OF COMMITTEES OF THE VICE-PRÉSIDENT ADJOINT DES COMITÉS PLÉNIERS WHOLE Pursuant to Order made Tuesday, October 5, 2004, the Speaker Conformément à l’ordre adopté le mardi 5 octobre 2004, le proposed that Ms. Augustine (Etobicoke—Lakeshore) be the Président propose que Mme Augustine (Etobicoke—Lakeshore) candidate for the position of Assistant Deputy Chair of soit la candidate au poste de vice-présidente adjointe des comités Committees of the Whole. pléniers. Accordingly, the motion “That Ms. Augustine (Etobicoke— En conséquence, la motion « Que Mme Augustine (Etobicoke Lakeshore) be appointed Assistant Deputy Chair of Committees of —Lakeshore) soit nommée vice-présidente adjointe des comités the Whole” was deemed to have been moved and seconded. -

Federal Government

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ◆ MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT ◆ HOUSE &SENATE COMMITTEES ◆ SENATORS ◆ FEDERAL MINISTRIES ◆ CAUCUS & CRITIC ◆ AGENCIES / CROWN RESPONSIBILITIES CORPORATIONS ◆ CANADIAN EMBASSIES ABROAD ◆ EMBASSIES TO CANADA 42 / FEDERAL RIDINGS FEDERAL RIDINGS Federal Statistics Alberta Total number of seats..............308 Total number of seats..............28 Conservative Party...................125 Conservative Party...................28 Liberal .......................................101 Calgary Centre ......................................Lee Richardson................................49 Bloc Québécois........................51 Calgary Centre-North............................Jim Prentice .....................................49 New Democratic Party .............29 Calgary East ..........................................Deepak Obhrai.................................49 Independent..............................2 Calgary Northeast .................................Art Hanger.......................................48 Calgary Southeast .................................Jason Kenney...................................49 Calgary Southwest ................................Stephen Harper ................................48 British Columbia Calgary West.........................................Rob Anders......................................48 Calgary-Nose Hill .................................Diane Ablonczy...............................48 Total number of seats..............36 Crowfoot ...............................................Kevin Sorenson ...............................49 -

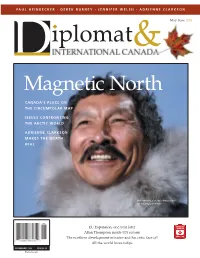

Diplomat MAY 05 FOR

P AUL HEINBECKER • DEREK BURNEY • JENNIFER WELSH • ADRIENNE CLARKSON May–June 2005 Magnetic North CANADA'S PLACE ON THE CIRCUMPOLAR MAP ISSUES CONFRONTING THE ARCTIC WORLD ADRIENNE CLARKSON MAKES THE NORTH REAL Jack Anawak, Canada's Ambassador for Circumpolar Affairs EU Expansion, one year later Allan Thompson inside UN reform The northern development minister and his critic face off All the world loves tulips ESTABLISHED 1989 CDN $5.95 PM 40957514 P AUL HEINBECKER • DEREK BURNEY • JENNIFER WELSH • ADRIENNE CLARKSON May–June 2005 Magnetic North CANADA'S PLACE ON THE CIRCUMPOLAR MAP ISSUES CONFRONTING THE ARCTIC WORLD ADRIENNE CLARKSON MAKES THE NORTH REAL Jack Anawak, Canada's Ambassador for Circumpolar Affairs EU Expansion, one year later Allan Thompson inside UN reform The northern development minister and his critic face off All the world loves tulips ESTABLISHED 1989 CDN $5.95 PM 40957514 Volume 16, Number 3 PUBLISHER Lezlee Cribb EDITOR Table of Jennifer Campbell ART DIRECTOR Paul Cavanaugh CONTRIBUTING EDITORS CONTENTS Daniel Drolet George Abraham DIPLOMATICA| CULTURE EDITOR Margo Roston Letters . 2 COPY EDITOR News and Culture . 5 Roger Bird Beyond the Headlines . 7 CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Recent Arrivals . 8 Jack Anawak Stephen Beckta Questioning James Bartleman . 9 Margaret Dickenson How Norway got autonomy . 10 Heather Exner Diplo-dates . 12 Michel Gauthier Ingvard Havnen Paul Heinbecker DISPATCHES| J.G. van Hellenberg Hubar Arctic Circles Gerard Kenney Lynette Murray Adrienne Clarkson’s northern eloquence . 14 Christina Spencer U Arctic: A worldly school . 16 Greg Poelzer New northern thinking . 17 Jim Prentice Face-off: Andy Scott and Jim Prentice . 18 Andy Scott Allan Thompson Peter Zimonjic Opposing Views .