14.11-From Perestroika to Putin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

02 Intro.Indd

AUGUST 1991 Introduction: Coup de Grâce? Ann E. Robertson The collapse of the Soviet N August 4, 1991, Soviet president Mikhail Gor- Obachev left for the Crimea, to relax at his newly con- Union was the product of a structed dacha in Foros. Russian president Boris Yeltsin retired to his dacha, a two-story building outside Moscow. multifaceted struggle for power Both leaders planned to return to work by August 20 to between the center (Moscow) sign a controversial new Union treaty. At the same time, opponents of the treaty were meet- and the extensive periphery. ing in secret near Moscow, debating whether to pre-empt the ceremony. These men held high-ranking positions in The August putsch was the all-Union institutions, such as the military, police, and critical tipping point at which intelligence services, and their power bases would be drastically reduced under the new confederal union. With the advantage shifted from the August 20 deadline looming, they resolved to seize power, overthrow Gorbachev, and preserve the Soviet Gorbachev to Yeltsin. Union. They failed on all counts. After the attempted coup failed, the editors of Problems of Communism solicited contributions for a special issue focusing on the August events. Starting from the assump- tion that “the swift, bloodless collapse of this abortive ‘state of emergency’ accelerated the very processes that the plotters hoped to block or reverse and effectively administered the coup de grâce to seven decades of Bol- shevik rule,”1 seven noted scholars were asked to analyze the August events and “reflect on the political, economic, social, and foreign policy ramifications of the disintegra- tion of the Soviet Union.”2 Their studies covered events through mid-October, when the November/December 1991 issue went to press. -

2 Russia and Democracy

RUSSIA AND 2 DEMOCRACY By Jeremy Kinsman, 2013 INTRODUCTION: UNDERSTANDING THE RUSSIAN EXPERIENCE he Russian struggle to transform from a totalitarian system to a homegrown T democracy has been fraught with challenges. Today, steps backward succeed and compete with those going forward. Democratic voices mingle with the boorish claims of presidential spokesmen that the democratic phase in Russia is done with, in favour of a patriotic authoritarian hybrid regime under the strong thumb of a charismatic egotist. Meanwhile, excluded by Russian government fat from further direct engagement in support of democratic development, Western democracies back away, though they are unwilling to abandon solidarity with Russia’s democrats and members of civil society seeking to widen democratic space in their country. Russia’s halting democratic transition has now spanned more than a quarter of a century. The Russian experience can teach much about the diffculties of transition to democratic governance, illuminating the perils of overconfdence surrounding the way developed democracies operated with regard to other countries’ experiences 20 years ago. This Russian case study is more about the policies of democratic governments than about the feld practice of diplomats. It is a study whose amendment in coming years and decades will be constant. RUSSIAN EXCEPTIONALISM As the Handbook insists, each national trajectory is unique. Russia’s towering exceptionalism is not, as US scholar Daniel Treisman (2012) reminds us, because the country has a particularly -

Thesis Full Manuscript Revised 2011V2

Regime Transition and Foreign Policy: The Case of Russia’s Approach to Central Asia (1991-2008) Glen Hazelton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2011 Abstract In 1991, Russian embarked on an ambitious regime transition to transform the country from communism to democracy. This would be a massive transformation, demanding economic, political, institutional, and social change. It was also expected that the transition would result in significant foreign policy adaptation, as Russia’s identity, direction and fundamental basis for policy-making was transformed. However, it was an unknown quantity how transition in the domestic environment would interact with foreign policy and what the nature of these changes would be. This thesis examines the relationship between regime transition and Russia’s foreign policy. It begins with an examination of literature on regime transition and the types of changes that potentially impact policy-making in a democratising state. It then moves to examining the policy environment and its impact on the contours of policy in each of the Yeltsin and Putin periods, drawing links between domestic changes and their expression in foreign policy. How these changes were expressed specifically is demonstrated through a case study of Russia’s approach to Central Asia through the Yeltsin and Putin periods. The thesis finds clearly that a domestic transitional politics was a determining factor in the nature, substance and style of Russia’s foreign relations. Under Yeltsin, sustained economic decline, contested visions of what Russia’s future should be and where its interests lay, as well as huge institutional flux, competition, an unstructured expansion of interests, conflict, and the inability to function effectively led to an environment of policy politicisation, inconsistency, and turmoil. -

Perestroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1993 Contracts in Conflict: erP estroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy Karl Glenn Hokenmaier Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hokenmaier, Karl Glenn, "Contracts in Conflict: erP estroika and the Decline of Soviet Legitimacy" (1993). Master's Theses. 775. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/775 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRACTS IN CONFLICT: PERESTROIKA AND THE DECLINE OF SOVIET LEGITIMACY by Karl Glenn Hokenmaier A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1993 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CONTRACTS IN CONFLICT: PERESTROIKA AND THE DECLINE OF SOVIET LEGITIMACY Karl Glenn Hokenmaier, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1993 Gorbachev’s perception of the Soviet Union’s socio-economic crisis and his subsequent actions to correct the economy and reform the political system were linked with attempts to renegotiate the social contract between the state and the Soviet people. However, reformulation of the social contract was incompatible with the conditions of a second arrangement between the leadership and the nomenklatura-the Soviet ruling class. -

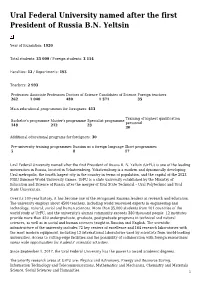

Ural Federal University Named After the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin Year of foundation: 1920 Total students: 35 000 / Foreign students: 3 114 Faculties: 12 / Departments: 193 Teachers: 2 993 Professors Associate Professors Doctors of Science Candidates of Science Foreign teachers 262 1 040 480 1 571 35 Main educational programmes for foreigners: 413 Training of highest qualification Bachelor's programme Master's programme Specialist programme personnel 148 212 23 30 Additional educational programs for foreigners: 30 Pre-university training programmes Russian as a foreign language Short programmes 5 8 17 Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B. N. Yeltsin (UrFU) is one of the leading universities in Russia, located in Yekaterinburg. Yekaterinburg is a modern and dynamically developing Ural metropolis, the fourth largest city in the country in terms of population, and the capital of the 2023 FISU Summer World University Games. UrFU is a state university established by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia after the merger of Ural State Technical – Ural Polytechnic and Ural State Universities. Over its 100-year history, it has become one of the recognized Russian leaders in research and education. The university employs about 4500 teachers, including world renowned experts in engineering and technology, natural, social and human sciences. More than 35,000 students from 101 countries of the world study at UrFU, and the university's alumni community exceeds 380 thousand people. 12 institutes provide more than 450 undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate programs in technical and natural sciences, as well as in social and human sciences taught in Russian and English. -

By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup

1 MEDIA AND MYSTERY IN. THE RUSSIAN COUP; By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup: Tbe Trutb and tbe Lessons~ By Mikhail Gorbachev. HarperCollins. 127 pp. $18.00 Tbe Future Belongs to Freedom~ By EduardShevardnadze. New York: The Free ,Press, 1991. 237 pp. Eyewitness; A Personal Account of the Unraveling of tbe Soviet Union. By Vladimir Pozner. Random House. 220 pp. $20.00 . Seven Days Tbat Sbooktbe World;Tbe Collapse of soviet communism. by stuart H. Loory and Ann Imse. Introduction by Hedrick Smith. CNN Report, Turner Publishing, Inc. 255 pp. Boris Yeltsin: From Bolsbevik to Democrat. By John Morrison. Dutton. 303pp. $20. Boris Yeltsin, A Political Biograpby. By Vladimir Solvyov and Elena Klepikova. Putnam. 320 pp. $24.95 We remember the Russian coup of A~gust 1991 as a quixotic attempt, doomed to failure, engineered by fools and thwarted by a spontaneous uprising. As Vladimir Pozner's Eyewitness puts it, our imag~ of the coup leaders is that of "faceless party hacks ••• Hollywood-cast to fit the somehow gross, repulsive, and yet somewhat comical image" of the typical Communist bureaucrat.(p. 10) Well, that image is false. More than that, it obscures the big story of the coup .and its consequences for Russia and the world. By falling back on a cold-war caricature ' and . accepting what Shevardnadze calls "the export version" of perestroika, the U.s. press, and Western media generally, may have missed the story of the decade. .' The men who struck on August 19, : 1991 were, as Pozner himself · argues,,"far from inept ,and, indeed, ' ready to do whatever was necessary to win. -

International and European Union Law

MYKOLAS ROMERIS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF LAW INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN UNION LAW OLESIA GORBUN (INTERNATIONAL LAW) THE STATUS OF THE KERCH STRAIT Master thesis Supervisor – prof. dr. Saulius Katuoka Consultant – dr. Skirmantė Klumbytė Vilnius, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... 9 1. THE GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE KERCH STRAIT ................................................................... 10 1.1. The Kerch Strait Before Occupation in 2014 .............................................................................. 10 1.2. The Kerch Strait After Occupation in 2014 and its Consequences ............................................. 14 2. CRITERIA FOR THE DETERMINATION THE KERCH STRAIT AS A “STRAIT USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION” ........................................................................................................ 25 2.1.Geographical criteria .................................................................................................................... 25 2.2. Functional criteria ....................................................................................................................... 28 3. LEGAL REGIME APPLICABLE IN THE KERCH STRAIT ............................................................... 30 3.1. The -

Russian Federation in the Era of Multipolarism

LA COMUNITÀ INTERNAZIONALE Rivista Trimestrale della Società Italiana per l’Organizzazione Internazionale QUADERNO 19 The Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation in the Era of Multipolarism: Practical Application of the Primakov Doctrine EDITORIALE SCIENTIFICA Napoli LA COMUNITÀ INTERNAZIONALE RIVISTA TRIMESTRALE DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA PER L’ORGANIZZAZIONE INTERNAZIONALE QUADERNI (Nuova Serie) 19 COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Pietro Gargiulo, Cesare Imbriani, Giuseppe Nesi, Adolfo Pepe, Attila Tanzi SOCIETÀ ITALIANA PER L’ORGANIZZAZIONE INTERNAZIONALE THE FOREIGN POLICY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IN THE ERA OF MULTIPOLARISM: PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE PRIMAKOV DOCTRINE EDITORIALE SCIENTIFICA Napoli Il presente Report è stato realizzato con il contributo dell’Unità di Analisi, Programmazione, Statistica e Documentazione Storica del Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, ai sensi dell’art. 23 bis del d.P.R. 18/1967. Le posizioni contenute nella presente pubblicazione sono espressione esclusivamente degli Autori e non rappresentano necessariamente le posizioni del Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale. Proprietà letteraria riservata Copyright 2020 Editoriale Scientifica srl Via San Biagio dei Librai, 39 89138 – Napoli ISBN 978-88-9391-752-0 INDICE FRANCO FRATTINI, President of the Italian Society for International Organisation (SIOI) and of the Institute for Eurasian Studies – Some Preliminary Considerations ……………….…….….……….…...…..……………………………. 7 ANDREA GIANNOTTI, Lecturer of History of International -

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1989

The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev 1989 Donated by A.S. Chernyaev to The National Security Archive Translated by Anna Melyakova Edited by Svetlana Savranskaya http://www.nsarchive.org Translation © The National Security Archive, 2009 The Diary of Anatoly S. Chernyaev, 1989 http://www.nsarchive.org January 1, 1989. The New Year has come. M.S.’1 speech was rather boring. The most important thing is that he did not make any sweet promises; but he could have given a more interesting analysis of the year. There was an open letter to Gorbachev from Ulyanov, Baklanov, Gelman, Klimov, Sagdeev, and Granin in the Moskovskie Novosti [Moscow News]. It is a new genre. We already know about the letters to Stalin, Dear Nikita Sergeyevich and Leonid Ilyich. But this letter has a position and voices demands. By the way, they remind him that back in the day, anybody at any leadership position who conducted the Party line sloppily, against personal convictions, and strained to make the bare minimum effort would be removed, if not shot. During the perestroika, however, we allow the vast majority to operate like this. January 15, 1989. Today the list of candidates for the CPSU People’s Deputies was published in newspapers. My last name is on the list. It was a great surprise to me to see my name among the “suggestions” that were handed out at registration to the CC Plenum participants. I am the only one of the General Secretary’s assistants who is among that hundred of guaranteed candidates. People noticed this. Moreover, I am the only one from the CC apparatus. -

Russian Politics and Society, Fourth Edition

Russian Politics and Society Having been fully revised and updated to reflect the considerable changes in Russia over the last decade, the fourth edition of this classic text builds on the strengths of the previous editions to provide a comprehensive and sophisticated analysis on Russian politics and society. In this edition, Richard Sakwa seeks to evaluate the evidence in a balanced and informed way, denying simplistic assumptions about the inevitable failure of the democratic exper- iment in Russia while avoiding facile generalisations on the inevitable triumph of global integration and democratisation. New to this edition: • Extended coverage of electoral laws, party development and regional politics • New chapter on the ‘phoney democracy’ period, 1991–3 • Historical evaluation of Yeltsin’s leadership • Full coverage of Putin’s presidency • Discussion of the development of civil society and the problems of democratic consolidation • Latest developments in the Chechnya conflict • More on foreign policy issues such as Russia’s relationship with NATO and the EU after enlargement, Russia’s relations with other post-Soviet states and the problem of competing ‘near abroads’ for Russia and the West • The re-introduction of the Russian constitution as an appendix • An updated select bibliography • More focus on the challenges facing Russia in the twenty-first century Written in an accessible and lively style, this book is packed with detailed information on the central debates and issues in Russia’s difficult transformation. This makes it the best available textbook on the subject and essential reading for all those concerned with the fate of Russia, and with the future of international society. -

On December 31, 1999,Yeltsin's Russia Became Putin's Russia

PROLOGUE n December 31, 1999,Yeltsin’s Russia became Putin’s Russia. Boris Yeltsin—a political maverick who until the end tried to Oplay the mutually exclusive roles of democrat and tsar, who made revolutionary frenzy and turmoil his way of survival—unexpect- edly left the Kremlin and handed over power, like a New Year’s gift, to Vladimir Putin, an unknown former intelligence officer who had hardly ever dreamed of becoming a Russian leader. Yeltsin—tired and sick, disoriented and having lost his stamina— apparently understood that he could no longer keep power in his fist. It was a painful and dramatic decision for a politician for whom nonstop struggle for power and domination was the substance of life and his main ambition. His failing health and numerous heart attacks, however, were not the main reasons behind his unexpected resignation. The moment came when Yeltsin could not control the situation much longer and—more important—he did not know how to deal with the new challenges Russia was facing. He had been accustomed to making breakthroughs, to defeating his enemies, to overcoming obstacles. He was not prepared for state building, for the effort of everyday governance, for consensus making, for knitting a new national unity. By nature he was a terminator, not a transformational leader. It was time for him to gra- ciously bow out and hand over power to his successor. And Russia had to live through a time of real suspense while the Kremlin was preparing the transfer of power. The new Russian leader Vladimir Putin has become a symbol of a staggering mix of continuity and change. -

Vladimir Putin and Russia's Newest

Association of Former Intelligence Officers The Intelligencer Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies 7700 Leesburg Pike Ste 324, Falls Church, VA 22043. Volume 22 • Number 2 • $15.00 single copy price Fall 2016 From AFIO's The Intelligencer Web: www.afio.com. Email: [email protected] Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Volume 22 • Number 2 • $15 single copy price Fall 2016 © 2016 AFIO - Association of Former Intelligence Officers, All • Karl Bauman – tried in 1937 and shot. Rights Reserved AAcAcAcAcAcctctcctttiiiivvvveveveveveveeeMMMeeeeeeaeaeaaasssssuuurrerererereeeeesssss • Grigory Sokolnikov (member first Politburo)– CoCouunntnttteeringring FFFaaalsselsehoodslsehohooooodsodss,,, DDiissttotoorrtrttteeedd Meeessssssaaagggeesess, arrested in 1937 (“Trial of 17”). Killed in prison and PrPProrooppapagaaggananddaa InInformation Wnfoformrmaattion WaWaarfare/Activerrfafarere/e/A/AcAccttiviveve Measures Measasurerees— — OverduerdrdueOverdue OvOveve ••• CouCounterntnteterringCountering tthethe VViirrtutuatalVirtual by the NKVD. CaCaCaliphaliphaattete •A• SA StratStrtrarategyratatteegyegy forgy foforr WinninWiWinningnningg WoWoWWorldorldrrldWWWaaar IVr IVIVV••• StSSttalin'staalialin'sn's's DiDiscDisciplissciplplee: Ve:Vladaddimimir VladVl ir PPutin andaandnd We"WPututin """WWeeett Affairs"AAffffafairAffairs"rs"s" ••• CIACIAIACIA ClandestineClandClandestineeesstine BroadcastingBroBroadroadcastingaddccasassting•• • Early EEaEaarlyrrlyly WWaWaarningarningtornrningo tot PoPoland TeTe•eaching acachingTPoland Intelligence: Intntetelligencce: Five FivFiveiveve