The Fate of the Russian State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism

Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism MARK R. BEISSINGER Abstract This article examines the role of nationalism in the collapse of communism in the late 1980s and early 1990s, arguing that nationalism (both in its presence and its absence, and in the various conflicts and disorders that it unleashed) played an important role in structuring the way in which communism collapsed. Two institutions of international and cultural control in particular – the Warsaw Pact and ethnofederalism – played key roles in determining which communist regimes failed and which survived. The article argues that the collapse of communism was not a series of isolated, individual national stories of resistance but a set of interrelated streams of activity in which action in one context profoundly affected action in other contexts – part of a larger tide of assertions of national sovereignty that swept through the Soviet empire during this period. That nationalism should be considered among the causes of the collapse of communism is not a view shared by everyone. A number of works on the end of communism in the Soviet Union have argued, for instance, that nationalism played only a minor role in the process – that the main events took place within official institutions in Moscow and had relatively little to do with society, or that nationalism was a marginal motivation or influence on the actions of those involved in key decision-making. Failed institutions and ideologies, an economy in decline, the burden of military competition with the United States and instrumental goals of self-enrichment among the nomenklatura instead loom large in these accounts.1 In many narratives of the end of communism, nationalism is portrayed merely as a consequence of communism’s demise, as a phase after communism disintegrated – not as an autonomous or contributing force within the process of collapse itself. -

Federalism in Eastern Europe During and After Communism

James Hughes Federalism in Eastern Europe during and after Communism Book section Original citation: Originally published in Fagan, Adam and Kopecký, Petr, (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of East European Politics. Routledge, London, UK. ISBN 9781138919754 © 2018 Routledge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/69642/ Available in LSE Research Online: March 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Federalism in Eastern Europe during and after Communism James Hughes Chapter 10 Forthcoming in Adam Fagan and Petr Kopecky eds. The Routledge Handbook of East European Politics. Routledge 2017 One of the earliest political visionaries of federalism in Eastern Europe,interwar Polish leader Józef Piłsudski, famously remarked to former socialist comrades that “we both took -

The South Caucasus 2018

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS 2018 FACTS, TRENDS, FUTURE SCENARIOS Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) is a political foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany. Democracy, peace and justice are the basic principles underlying the activities of KAS at home as well as abroad. The Foundation’s Regional Program South Caucasus conducts projects aiming at: Strengthening democratization processes, Promoting political participation of the people, Supporting social justice and sustainable economic development, Promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Supporting the region’s rapprochement with European structures. All rights reserved. Printed in Georgia. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Regional Program South Caucasus Akhvlediani Aghmarti 9a 0103 Tbilisi, Georgia www.kas.de/kaukasus Disclaimer The papers in this volume reflect the personal opinions of the authors and not those of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation or any other organizations, including the organizations with which the authors are affiliated. ISBN 978-9941-0-5882-0 © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V 2013 Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER I POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION: SHADOWS OF THE PAST, FACTS AND ANTICIPATIONS The Political Dimension: Armenian Perspective By Richard Giragosian .................................................................................................. 9 The Influence Level of External Factors on the Political Transformations in Azerbaijan since Independence By Rovshan Ibrahimov -

02 Intro.Indd

AUGUST 1991 Introduction: Coup de Grâce? Ann E. Robertson The collapse of the Soviet N August 4, 1991, Soviet president Mikhail Gor- Obachev left for the Crimea, to relax at his newly con- Union was the product of a structed dacha in Foros. Russian president Boris Yeltsin retired to his dacha, a two-story building outside Moscow. multifaceted struggle for power Both leaders planned to return to work by August 20 to between the center (Moscow) sign a controversial new Union treaty. At the same time, opponents of the treaty were meet- and the extensive periphery. ing in secret near Moscow, debating whether to pre-empt the ceremony. These men held high-ranking positions in The August putsch was the all-Union institutions, such as the military, police, and critical tipping point at which intelligence services, and their power bases would be drastically reduced under the new confederal union. With the advantage shifted from the August 20 deadline looming, they resolved to seize power, overthrow Gorbachev, and preserve the Soviet Gorbachev to Yeltsin. Union. They failed on all counts. After the attempted coup failed, the editors of Problems of Communism solicited contributions for a special issue focusing on the August events. Starting from the assump- tion that “the swift, bloodless collapse of this abortive ‘state of emergency’ accelerated the very processes that the plotters hoped to block or reverse and effectively administered the coup de grâce to seven decades of Bol- shevik rule,”1 seven noted scholars were asked to analyze the August events and “reflect on the political, economic, social, and foreign policy ramifications of the disintegra- tion of the Soviet Union.”2 Their studies covered events through mid-October, when the November/December 1991 issue went to press. -

Ethnic Violence in the Former Soviet Union Richard H

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Ethnic Violence in the Former Soviet Union Richard H. Hawley Jr. (Richard Howard) Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES ETHNIC VIOLENCE IN THE FORMER SOVIET UNION By RICHARD H. HAWLEY, JR. A Dissertation submitted to the Political Science Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Richard H. Hawley, Jr. defended this dissertation on August 26, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Heemin Kim Professor Directing Dissertation Jonathan Grant University Representative Dale Smith Committee Member Charles Barrilleaux Committee Member Lee Metcalf Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my father, Richard H. Hawley, Sr. and To my mother, Catherine S. Hawley (in loving memory) iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who made this dissertation possible, and I extend my heartfelt gratitude to all of them. Above all, I thank my committee chair, Dr. Heemin Kim, for his understanding, patience, guidance, and comments. Next, I extend my appreciation to Dr. Dale Smith, a committee member and department chair, for his encouragement to me throughout all of my years as a doctoral student at the Florida State University. I am grateful for the support and feedback of my other committee members, namely Dr. -

Thesis Full Manuscript Revised 2011V2

Regime Transition and Foreign Policy: The Case of Russia’s Approach to Central Asia (1991-2008) Glen Hazelton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2011 Abstract In 1991, Russian embarked on an ambitious regime transition to transform the country from communism to democracy. This would be a massive transformation, demanding economic, political, institutional, and social change. It was also expected that the transition would result in significant foreign policy adaptation, as Russia’s identity, direction and fundamental basis for policy-making was transformed. However, it was an unknown quantity how transition in the domestic environment would interact with foreign policy and what the nature of these changes would be. This thesis examines the relationship between regime transition and Russia’s foreign policy. It begins with an examination of literature on regime transition and the types of changes that potentially impact policy-making in a democratising state. It then moves to examining the policy environment and its impact on the contours of policy in each of the Yeltsin and Putin periods, drawing links between domestic changes and their expression in foreign policy. How these changes were expressed specifically is demonstrated through a case study of Russia’s approach to Central Asia through the Yeltsin and Putin periods. The thesis finds clearly that a domestic transitional politics was a determining factor in the nature, substance and style of Russia’s foreign relations. Under Yeltsin, sustained economic decline, contested visions of what Russia’s future should be and where its interests lay, as well as huge institutional flux, competition, an unstructured expansion of interests, conflict, and the inability to function effectively led to an environment of policy politicisation, inconsistency, and turmoil. -

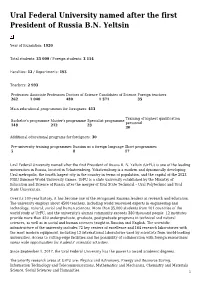

Ural Federal University Named After the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin Year of foundation: 1920 Total students: 35 000 / Foreign students: 3 114 Faculties: 12 / Departments: 193 Teachers: 2 993 Professors Associate Professors Doctors of Science Candidates of Science Foreign teachers 262 1 040 480 1 571 35 Main educational programmes for foreigners: 413 Training of highest qualification Bachelor's programme Master's programme Specialist programme personnel 148 212 23 30 Additional educational programs for foreigners: 30 Pre-university training programmes Russian as a foreign language Short programmes 5 8 17 Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B. N. Yeltsin (UrFU) is one of the leading universities in Russia, located in Yekaterinburg. Yekaterinburg is a modern and dynamically developing Ural metropolis, the fourth largest city in the country in terms of population, and the capital of the 2023 FISU Summer World University Games. UrFU is a state university established by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia after the merger of Ural State Technical – Ural Polytechnic and Ural State Universities. Over its 100-year history, it has become one of the recognized Russian leaders in research and education. The university employs about 4500 teachers, including world renowned experts in engineering and technology, natural, social and human sciences. More than 35,000 students from 101 countries of the world study at UrFU, and the university's alumni community exceeds 380 thousand people. 12 institutes provide more than 450 undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate programs in technical and natural sciences, as well as in social and human sciences taught in Russian and English. -

International and European Union Law

MYKOLAS ROMERIS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF LAW INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN UNION LAW OLESIA GORBUN (INTERNATIONAL LAW) THE STATUS OF THE KERCH STRAIT Master thesis Supervisor – prof. dr. Saulius Katuoka Consultant – dr. Skirmantė Klumbytė Vilnius, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... 9 1. THE GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE KERCH STRAIT ................................................................... 10 1.1. The Kerch Strait Before Occupation in 2014 .............................................................................. 10 1.2. The Kerch Strait After Occupation in 2014 and its Consequences ............................................. 14 2. CRITERIA FOR THE DETERMINATION THE KERCH STRAIT AS A “STRAIT USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION” ........................................................................................................ 25 2.1.Geographical criteria .................................................................................................................... 25 2.2. Functional criteria ....................................................................................................................... 28 3. LEGAL REGIME APPLICABLE IN THE KERCH STRAIT ............................................................... 30 3.1. The -

Russian Federation in the Era of Multipolarism

LA COMUNITÀ INTERNAZIONALE Rivista Trimestrale della Società Italiana per l’Organizzazione Internazionale QUADERNO 19 The Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation in the Era of Multipolarism: Practical Application of the Primakov Doctrine EDITORIALE SCIENTIFICA Napoli LA COMUNITÀ INTERNAZIONALE RIVISTA TRIMESTRALE DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA PER L’ORGANIZZAZIONE INTERNAZIONALE QUADERNI (Nuova Serie) 19 COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Pietro Gargiulo, Cesare Imbriani, Giuseppe Nesi, Adolfo Pepe, Attila Tanzi SOCIETÀ ITALIANA PER L’ORGANIZZAZIONE INTERNAZIONALE THE FOREIGN POLICY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION IN THE ERA OF MULTIPOLARISM: PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE PRIMAKOV DOCTRINE EDITORIALE SCIENTIFICA Napoli Il presente Report è stato realizzato con il contributo dell’Unità di Analisi, Programmazione, Statistica e Documentazione Storica del Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale, ai sensi dell’art. 23 bis del d.P.R. 18/1967. Le posizioni contenute nella presente pubblicazione sono espressione esclusivamente degli Autori e non rappresentano necessariamente le posizioni del Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale. Proprietà letteraria riservata Copyright 2020 Editoriale Scientifica srl Via San Biagio dei Librai, 39 89138 – Napoli ISBN 978-88-9391-752-0 INDICE FRANCO FRATTINI, President of the Italian Society for International Organisation (SIOI) and of the Institute for Eurasian Studies – Some Preliminary Considerations ……………….…….….……….…...…..……………………………. 7 ANDREA GIANNOTTI, Lecturer of History of International -

Russian Politics and Society, Fourth Edition

Russian Politics and Society Having been fully revised and updated to reflect the considerable changes in Russia over the last decade, the fourth edition of this classic text builds on the strengths of the previous editions to provide a comprehensive and sophisticated analysis on Russian politics and society. In this edition, Richard Sakwa seeks to evaluate the evidence in a balanced and informed way, denying simplistic assumptions about the inevitable failure of the democratic exper- iment in Russia while avoiding facile generalisations on the inevitable triumph of global integration and democratisation. New to this edition: • Extended coverage of electoral laws, party development and regional politics • New chapter on the ‘phoney democracy’ period, 1991–3 • Historical evaluation of Yeltsin’s leadership • Full coverage of Putin’s presidency • Discussion of the development of civil society and the problems of democratic consolidation • Latest developments in the Chechnya conflict • More on foreign policy issues such as Russia’s relationship with NATO and the EU after enlargement, Russia’s relations with other post-Soviet states and the problem of competing ‘near abroads’ for Russia and the West • The re-introduction of the Russian constitution as an appendix • An updated select bibliography • More focus on the challenges facing Russia in the twenty-first century Written in an accessible and lively style, this book is packed with detailed information on the central debates and issues in Russia’s difficult transformation. This makes it the best available textbook on the subject and essential reading for all those concerned with the fate of Russia, and with the future of international society. -

Boris Yeltsin and the Failure of Shock Therapy Christopher Huygen

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: Boris Yeltsin and the Failure of Shock Therapy Christopher Huygen Abstract The collapse of the Soviet Union created unprecedented dilemmas for the leaders of the new independent Russia. Shedding the communist past, Boris Yeltsin embarked on an ambitious program to reorganize Russia‟s political and economic systems. Known as „shock therapy,‟ Yeltsin advocated a rapid transition from state planning to a market economy while simultaneously introducing democracy to Russia. Expecting a short period of hardship as economic reforms opened Russia to world markets, followed by prolonged growth and prosperity, Yeltsin‟s societal upheaval left Russia a prostrate state, mired in a depression that left many longing for a return to socialism. This paper argues that the economic policies of shock therapy were an unmitigated failure. Four overarching factors will be analyzed to provide a foundational understanding of the social, economic, and international circumstances that made shock therapy‟s methods ineffective. Adopted before Russia was institutionally and politically prepared, the simultaneous transition to capitalism and democracy hindered the Russian state‟s ability to ensure a stable atmosphere to conduct business, while old guard communists obstructed progress by resisting radical change. Economic instability engendered by shock therapy reverberated throughout Russian society, creating political anxiety and lowering living standards that undermined the popular support crucial to the program‟s success. Shortsighted policies and inept privatization practices allowed a small conglomerate of business elites to gain control of Russia‟s most profitable industries, creating a class of oligarchs uninterested in reinvesting capital but skilled in circumventing Russia‟s tax laws. -

Breakthrough to Freedom

The International Foundation for SocioEconomic and Political Studies (The Gorbachev Foundation) BREAKTHROUGH TO FREEDOM PERESTROIKA: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS R.VALENT PUBLISHERS 2009 Compiled by Viktor Kuvaldin, Professor, Doctor of History Executive Editor: Aleksandr Veber, CONTENTS Doctor of History Translation: Tatiana Belyak, Konstantin Petrenko To the Reader . .5 Page makeup: Viktoriya Kolesnichenko Art design: R.Valent Publishers PART I. Seven Years that Changed the Country and the World Publisher’s Acknowledgement: Special thanks to Mr. Mikhail Selivanov, Vadim Medvedev. Perestroika’s Chance of Success . .8 who helped make this book possible. Stephen F. Cohen. Was the Soviet System Reformable? . .22 ISBN 9785934392629 Archie Brown. Perestroika and the Five Transformations . .40 Aleksandr Galkin. The Place of Perestroika in the History of Russia . .58 Viktor Kuvaldin. Three Forks in the Road of Gorbachev’s Perestroika . .73 Breakthrough to Freedom. Perestroika: A Critical Analysis. Aleksandr Veber. Perestroika and International Social Democracy . .95 M., R.Valent Publishers, 2009, — 304 pages. Boris Slavin. Perestroika in the Mirror of Modern Interpretations . .111 Jack F. Matlock, Jr. Perestroika as Viewed from Washington, 19851991 . .126 Copyright © 2009 by the International PART II. Our Times and Ourselves Foundation for SocioEconomic and Political Studies (The Gorbachev Foundation) Aleksandr Nekipelov. Is It Easy to Catch a Black Cat in a Dark Room, Copyright © R.Valent Publishers Even If It Is There? . .144 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means Oleg Bogomolov. A Turning Point in History: without written permission of the copyright Reflections of an EyeWitness . .152 holders. Nikolay Shmelev. Bloodshed Is Not Inevitable .