02 Intro.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Geopolitical Storylines and Public Opinion in the Wake of 9–11: a Critical Geopolitical Analysis and National Survey

Communist and Post-Communist Studies 37 (2004) 281–318 www.elsevier.com/locate/postcomstud Russian geopolitical storylines and public opinion in the wake of 9–11: a critical geopolitical analysis and national survey John O’Loughlin a,Ã, Gearoid O´ Tuathail b, Vladimir Kolossov c a Department of Geography and Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Campus Box 487, Boulder, CO80309-0487, USA b Government and International Affairs, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Alexandria Center, VA 22314–2979, USA c Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Abstract Examination of the speeches, writings and editorials by the Putin Administration in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks showed a consistent storyline that equated Russia’s war against Chechen terrorists with the subsequent US attack on the Tali- ban and Al Qaeda. The storyline made a strong case for a Russian alliance with the US and the West against those who were attacking the ‘civilized world’. Two alternative storylines also emerged. The centrist-liberal storyline was skeptical of the benefits accruing to Russia from its support of the Bush Administration’s policy, while the national patriotic-Communist storyline concentrated on the ‘imperialist’ drive of the United States to control the resources of Eurasia. The resonance of the dominant Putin storyline and its skeptical and suspicious alternatives among the Russian public is tested by analysis of the responses to a representa- tive national survey of 1800 adults conducted in April 2002. Significant socio-demographic differences appear in responses to eight questions. The Putin storyline is accepted by the rich supporters of the Edinstvo party, males, ‘Westernizers’, residents of Siberia, singles and young adults, while the oppositional storylines are supported by Communist party suppor- ters, the elderly, Muslims, women, the poor, and residents of Moscow and St. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation

Organized Crime and the Russian State Challenges to U.S.-Russian Cooperation J. MICHAEL WALLER "They write I'm the mafia's godfather. It was Vladimir Ilich Lenin who was the real organizer of the mafia and who set up the criminal state." -Otari Kvantrishvili, Moscow organized crime leader.l "Criminals Nave already conquered the heights of the state-with the chief of the KGB as head of a mafia group." -Former KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin.2 Introduction As the United States and Russia launch a Great Crusade against organized crime, questions emerge not only about the nature of joint cooperation, but about the nature of organized crime itself. In addition to narcotics trafficking, financial fraud and racketecring, Russian organized crime poses an even greater danger: the theft and t:rafficking of weapons of mass destruction. To date, most of the discussion of organized crime based in Russia and other former Soviet republics has emphasized the need to combat conven- tional-style gangsters and high-tech terrorists. These forms of criminals are a pressing danger in and of themselves, but the problem is far more profound. Organized crime-and the rarnpant corruption that helps it flourish-presents a threat not only to the security of reforms in Russia, but to the United States as well. The need for cooperation is real. The question is, Who is there in Russia that the United States can find as an effective partner? "Superpower of Crime" One of the greatest mistakes the West can make in working with former Soviet republics to fight organized crime is to fall into the trap of mirror- imaging. -

KGB Boss Says Robert Maxwell Was the Second Kissinger

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 32, August 12, 1994 boss says Robert axwe KGB M ll was the second Kissinger by Mark Burdman On the evening of July 28, Germany's ARD television net Margaret Thatcher, who was frantically trying to prevent work broadcast an extraordinary documentary on the life German reunification. and death of the late Robert Maxwell, the British publishing Stanislav Sorokin was one of several top-level former magnate and sleazy wheeler-and-dealer who died under mys Soviet intelligence and political insiders who freely com terious circumstances, his body found floating in the waters mented on Maxwell during the broadcast. For their own rea off Tenerife in the Canary Islands, on Nov. 5, 1991. The sons, these Russians are evidently intent on provoking an show, "Man Overboard," was co-produced by the firm Mit international discussion of, and investigation into, the mys teldeutscher Rundfunk, headquartered in Leipzig in eastern teries of capital flight operations out of the U.S.S.R. in the Germany, and Austria's Oesterreicher Rundfunk. It relied late 1980s-early 1990s. Former Soviet KGB chief Vladimir primarily on interviews with senior officials of the former Kryuchkov, a partner of Maxwell in numerous underhanded Soviet KGB and GRU intelligence services, who helped ventures who went to jail for his role in the failed August build the case that the circumstances of Maxwell's death 1991 putsch against Gorbachov, suggests in the concluding must have been intimately linked to efforts to cover up sensi moments of the broadcast, that f'the English-American [sic] tive Soviet Communist Party capital flightand capital transfer secret services, who are experienced enough, could, if they to the West in the last days of the U.S.S.R. -

The Soviet Coup: a Command, Control, and Communications Analysis

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1992-03 The Soviet coup: a command, control, and communications analysis Herbert, Joseph Howard Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/24041 DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOO! MONTEREY CA 93943-5101 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS THE SOVIET COUP: A COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNICATIONS ANALYSIS by Joseph Howard Herbert March, 1992 Principal Advisor: R. Mitchell Brown III Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited UINULASSIMIDD SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE la REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb. RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS UNCLASSIFIED 2a SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY OF REPORT Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 2b DECLASSIFICATION/DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE 4 PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5. MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 6a NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b OFFICE SYMBOL 7a. NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School (If applicable) Naval Postgraduate School 55 6c ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b. ADDRESS (Crty, State, and ZIP Code) Monterey, CA 93943-5000 Monterey, CA 93943-5000 8a. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING 8b. OFFICE SYMBOL 9. PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If applicable) 8c ADDRESS (Crty, State, and ZIP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS Program Element No Work Unit Acce&iion Number 1 1 TITLE (Include Security Classification) THE SOVIET COUP: A COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNICATIONS ANALYSIS 12 PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Herbert, Joseph, Howard 13a. TYPE OF REPORT 13b TIME COVERED 14. DATE OF REPORT (year, month, day) 15 PAGE COUNT Master's Thesis From To 92 March 79 16 SUPPLEMENTARY NOTATION The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. -

Domestic and Foreign Problems of the Brezhnev Era CHAPTER 5 Domestic and Foreign Problems of the Brezhnev Era

Chapter 5: Domestic and foreign problems of the Brezhnev era CHAPTER 5 Domestic and foreign problems of the Brezhnev era This chapter analyses Leonid Brezhnev’s rule of the USSR until his death in 1982. The extent to which this was an era of political, economic and social stagnation is fully explored. Soviet foreign policy in the 1970s is also discussed, in particular the reasons for the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and its consequences. You need to consider the following questions throughout this chapter: + What were the key features of the USSR’s politics, society and economy under Brezhnev? + Was Brezhnev’s leadership to blame for Soviet stagnation from 1964 to 1982? + What challenges did Soviet foreign policy face in the Brezhnev era? + To what extent were the USSR’s aims achieved in Afghanistan? + Why did the USSR invade Afghanistan? + How serious were the socio-economic and political problems confronting the USSR by the time of Brezhnev’s death? 1 Politics, economy and society under Brezhnev Key question: What were the key features of the USSR’s politics, society and economy under Brezhnev? By 1964, Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of KEY TERM the Soviet Union (CPSU), was viewed by senior party members as increasingly unable to exercise the necessary leadership and stability Presidium Dominant, required for the USSR to uphold its world position. policy-making body within the CPSU formed by the Khrushchev was removed from party leadership following a plot by Council of Ministers, members of the Presidium, in which Leonid Brezhnev played a leading part. -

The Fifteenth Anniversary of the End of the Soviet Union: Recollections and Perspectives Conference Proceedings Edited by Markian Dobczansky

The Fifteenth Anniversary of the End of the Soviet Union: Recollections and Perspectives Conference Proceedings Edited by Markian Dobczansky Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars OCCASIONAL PAPER #299 KENNAN One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW INSTITUTE Washington, DC 20004-3027 Tel. (202) 691-4100 Fax (202) 691-4247 www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan ISBN 1-933549-34-3 The Kennan Institute is a division of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Through its programs of residential scholarships, meetings, and publications, the Institute encourages scholarship on the successor states to the Soviet Union, embracing a broad range of fields in the social sciences and humanities. The Kennan Institute is supported by contributions from foundations, corporations, individuals, and the United States Government. Kennan Institute Occasional Papers The Kennan Institute makes Occasional Papers available to all those interested. Occasional Papers are submitted by Kennan Institute scholars and visiting speakers. Copies of Occasional Papers and a list of papers currently available can be obtained free of charge by contacting: Occasional Papers Kennan Institute One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 (202) 691-4100 Occasional Papers published since 1999 are available on the Institute’s web site, www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan. This Occasional Paper has been produced with the support of the Program for Research and Training on Eastern Europe and the Independent States of the Former Soviet Union of the U.S. Department of State (fund- ed by the Soviet and East European Research and Training Act of 1983, or Title VIII). The Kennan Institute is most grateful for this support. -

Thesis Full Manuscript Revised 2011V2

Regime Transition and Foreign Policy: The Case of Russia’s Approach to Central Asia (1991-2008) Glen Hazelton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2011 Abstract In 1991, Russian embarked on an ambitious regime transition to transform the country from communism to democracy. This would be a massive transformation, demanding economic, political, institutional, and social change. It was also expected that the transition would result in significant foreign policy adaptation, as Russia’s identity, direction and fundamental basis for policy-making was transformed. However, it was an unknown quantity how transition in the domestic environment would interact with foreign policy and what the nature of these changes would be. This thesis examines the relationship between regime transition and Russia’s foreign policy. It begins with an examination of literature on regime transition and the types of changes that potentially impact policy-making in a democratising state. It then moves to examining the policy environment and its impact on the contours of policy in each of the Yeltsin and Putin periods, drawing links between domestic changes and their expression in foreign policy. How these changes were expressed specifically is demonstrated through a case study of Russia’s approach to Central Asia through the Yeltsin and Putin periods. The thesis finds clearly that a domestic transitional politics was a determining factor in the nature, substance and style of Russia’s foreign relations. Under Yeltsin, sustained economic decline, contested visions of what Russia’s future should be and where its interests lay, as well as huge institutional flux, competition, an unstructured expansion of interests, conflict, and the inability to function effectively led to an environment of policy politicisation, inconsistency, and turmoil. -

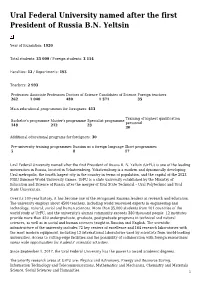

Ural Federal University Named After the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin Year of foundation: 1920 Total students: 35 000 / Foreign students: 3 114 Faculties: 12 / Departments: 193 Teachers: 2 993 Professors Associate Professors Doctors of Science Candidates of Science Foreign teachers 262 1 040 480 1 571 35 Main educational programmes for foreigners: 413 Training of highest qualification Bachelor's programme Master's programme Specialist programme personnel 148 212 23 30 Additional educational programs for foreigners: 30 Pre-university training programmes Russian as a foreign language Short programmes 5 8 17 Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B. N. Yeltsin (UrFU) is one of the leading universities in Russia, located in Yekaterinburg. Yekaterinburg is a modern and dynamically developing Ural metropolis, the fourth largest city in the country in terms of population, and the capital of the 2023 FISU Summer World University Games. UrFU is a state university established by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia after the merger of Ural State Technical – Ural Polytechnic and Ural State Universities. Over its 100-year history, it has become one of the recognized Russian leaders in research and education. The university employs about 4500 teachers, including world renowned experts in engineering and technology, natural, social and human sciences. More than 35,000 students from 101 countries of the world study at UrFU, and the university's alumni community exceeds 380 thousand people. 12 institutes provide more than 450 undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate programs in technical and natural sciences, as well as in social and human sciences taught in Russian and English. -

By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup

1 MEDIA AND MYSTERY IN. THE RUSSIAN COUP; By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup: Tbe Trutb and tbe Lessons~ By Mikhail Gorbachev. HarperCollins. 127 pp. $18.00 Tbe Future Belongs to Freedom~ By EduardShevardnadze. New York: The Free ,Press, 1991. 237 pp. Eyewitness; A Personal Account of the Unraveling of tbe Soviet Union. By Vladimir Pozner. Random House. 220 pp. $20.00 . Seven Days Tbat Sbooktbe World;Tbe Collapse of soviet communism. by stuart H. Loory and Ann Imse. Introduction by Hedrick Smith. CNN Report, Turner Publishing, Inc. 255 pp. Boris Yeltsin: From Bolsbevik to Democrat. By John Morrison. Dutton. 303pp. $20. Boris Yeltsin, A Political Biograpby. By Vladimir Solvyov and Elena Klepikova. Putnam. 320 pp. $24.95 We remember the Russian coup of A~gust 1991 as a quixotic attempt, doomed to failure, engineered by fools and thwarted by a spontaneous uprising. As Vladimir Pozner's Eyewitness puts it, our imag~ of the coup leaders is that of "faceless party hacks ••• Hollywood-cast to fit the somehow gross, repulsive, and yet somewhat comical image" of the typical Communist bureaucrat.(p. 10) Well, that image is false. More than that, it obscures the big story of the coup .and its consequences for Russia and the world. By falling back on a cold-war caricature ' and . accepting what Shevardnadze calls "the export version" of perestroika, the U.s. press, and Western media generally, may have missed the story of the decade. .' The men who struck on August 19, : 1991 were, as Pozner himself · argues,,"far from inept ,and, indeed, ' ready to do whatever was necessary to win. -

International and European Union Law

MYKOLAS ROMERIS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF LAW INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN UNION LAW OLESIA GORBUN (INTERNATIONAL LAW) THE STATUS OF THE KERCH STRAIT Master thesis Supervisor – prof. dr. Saulius Katuoka Consultant – dr. Skirmantė Klumbytė Vilnius, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... 9 1. THE GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE KERCH STRAIT ................................................................... 10 1.1. The Kerch Strait Before Occupation in 2014 .............................................................................. 10 1.2. The Kerch Strait After Occupation in 2014 and its Consequences ............................................. 14 2. CRITERIA FOR THE DETERMINATION THE KERCH STRAIT AS A “STRAIT USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION” ........................................................................................................ 25 2.1.Geographical criteria .................................................................................................................... 25 2.2. Functional criteria ....................................................................................................................... 28 3. LEGAL REGIME APPLICABLE IN THE KERCH STRAIT ............................................................... 30 3.1. The -

Click Here to Download the PDF File

FROM SOVIET DICTATORSHIP TO RUSSIAN DERMO-CRATIA: TOWARD A THEORY OF POLITICAL JUSTICE BY YANA GOROKHOVSKAIA, B.A. (HONS) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Law Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario August 2009 ©2009, Yana Gorokhovskaia Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your We Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60308-6 Our file Notre r&ference ISBN: 978-0-494-60308-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.