Russian Federation in the Era of Multipolarism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

02 Intro.Indd

AUGUST 1991 Introduction: Coup de Grâce? Ann E. Robertson The collapse of the Soviet N August 4, 1991, Soviet president Mikhail Gor- Obachev left for the Crimea, to relax at his newly con- Union was the product of a structed dacha in Foros. Russian president Boris Yeltsin retired to his dacha, a two-story building outside Moscow. multifaceted struggle for power Both leaders planned to return to work by August 20 to between the center (Moscow) sign a controversial new Union treaty. At the same time, opponents of the treaty were meet- and the extensive periphery. ing in secret near Moscow, debating whether to pre-empt the ceremony. These men held high-ranking positions in The August putsch was the all-Union institutions, such as the military, police, and critical tipping point at which intelligence services, and their power bases would be drastically reduced under the new confederal union. With the advantage shifted from the August 20 deadline looming, they resolved to seize power, overthrow Gorbachev, and preserve the Soviet Gorbachev to Yeltsin. Union. They failed on all counts. After the attempted coup failed, the editors of Problems of Communism solicited contributions for a special issue focusing on the August events. Starting from the assump- tion that “the swift, bloodless collapse of this abortive ‘state of emergency’ accelerated the very processes that the plotters hoped to block or reverse and effectively administered the coup de grâce to seven decades of Bol- shevik rule,”1 seven noted scholars were asked to analyze the August events and “reflect on the political, economic, social, and foreign policy ramifications of the disintegra- tion of the Soviet Union.”2 Their studies covered events through mid-October, when the November/December 1991 issue went to press. -

Thesis Full Manuscript Revised 2011V2

Regime Transition and Foreign Policy: The Case of Russia’s Approach to Central Asia (1991-2008) Glen Hazelton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2011 Abstract In 1991, Russian embarked on an ambitious regime transition to transform the country from communism to democracy. This would be a massive transformation, demanding economic, political, institutional, and social change. It was also expected that the transition would result in significant foreign policy adaptation, as Russia’s identity, direction and fundamental basis for policy-making was transformed. However, it was an unknown quantity how transition in the domestic environment would interact with foreign policy and what the nature of these changes would be. This thesis examines the relationship between regime transition and Russia’s foreign policy. It begins with an examination of literature on regime transition and the types of changes that potentially impact policy-making in a democratising state. It then moves to examining the policy environment and its impact on the contours of policy in each of the Yeltsin and Putin periods, drawing links between domestic changes and their expression in foreign policy. How these changes were expressed specifically is demonstrated through a case study of Russia’s approach to Central Asia through the Yeltsin and Putin periods. The thesis finds clearly that a domestic transitional politics was a determining factor in the nature, substance and style of Russia’s foreign relations. Under Yeltsin, sustained economic decline, contested visions of what Russia’s future should be and where its interests lay, as well as huge institutional flux, competition, an unstructured expansion of interests, conflict, and the inability to function effectively led to an environment of policy politicisation, inconsistency, and turmoil. -

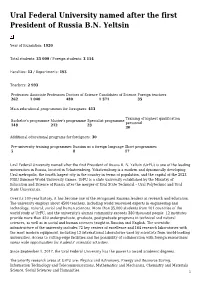

Ural Federal University Named After the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin Year of foundation: 1920 Total students: 35 000 / Foreign students: 3 114 Faculties: 12 / Departments: 193 Teachers: 2 993 Professors Associate Professors Doctors of Science Candidates of Science Foreign teachers 262 1 040 480 1 571 35 Main educational programmes for foreigners: 413 Training of highest qualification Bachelor's programme Master's programme Specialist programme personnel 148 212 23 30 Additional educational programs for foreigners: 30 Pre-university training programmes Russian as a foreign language Short programmes 5 8 17 Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B. N. Yeltsin (UrFU) is one of the leading universities in Russia, located in Yekaterinburg. Yekaterinburg is a modern and dynamically developing Ural metropolis, the fourth largest city in the country in terms of population, and the capital of the 2023 FISU Summer World University Games. UrFU is a state university established by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia after the merger of Ural State Technical – Ural Polytechnic and Ural State Universities. Over its 100-year history, it has become one of the recognized Russian leaders in research and education. The university employs about 4500 teachers, including world renowned experts in engineering and technology, natural, social and human sciences. More than 35,000 students from 101 countries of the world study at UrFU, and the university's alumni community exceeds 380 thousand people. 12 institutes provide more than 450 undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate programs in technical and natural sciences, as well as in social and human sciences taught in Russian and English. -

International and European Union Law

MYKOLAS ROMERIS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF LAW INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN UNION LAW OLESIA GORBUN (INTERNATIONAL LAW) THE STATUS OF THE KERCH STRAIT Master thesis Supervisor – prof. dr. Saulius Katuoka Consultant – dr. Skirmantė Klumbytė Vilnius, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................... 9 1. THE GENERAL OVERVIEW OF THE KERCH STRAIT ................................................................... 10 1.1. The Kerch Strait Before Occupation in 2014 .............................................................................. 10 1.2. The Kerch Strait After Occupation in 2014 and its Consequences ............................................. 14 2. CRITERIA FOR THE DETERMINATION THE KERCH STRAIT AS A “STRAIT USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION” ........................................................................................................ 25 2.1.Geographical criteria .................................................................................................................... 25 2.2. Functional criteria ....................................................................................................................... 28 3. LEGAL REGIME APPLICABLE IN THE KERCH STRAIT ............................................................... 30 3.1. The -

Russian Politics and Society, Fourth Edition

Russian Politics and Society Having been fully revised and updated to reflect the considerable changes in Russia over the last decade, the fourth edition of this classic text builds on the strengths of the previous editions to provide a comprehensive and sophisticated analysis on Russian politics and society. In this edition, Richard Sakwa seeks to evaluate the evidence in a balanced and informed way, denying simplistic assumptions about the inevitable failure of the democratic exper- iment in Russia while avoiding facile generalisations on the inevitable triumph of global integration and democratisation. New to this edition: • Extended coverage of electoral laws, party development and regional politics • New chapter on the ‘phoney democracy’ period, 1991–3 • Historical evaluation of Yeltsin’s leadership • Full coverage of Putin’s presidency • Discussion of the development of civil society and the problems of democratic consolidation • Latest developments in the Chechnya conflict • More on foreign policy issues such as Russia’s relationship with NATO and the EU after enlargement, Russia’s relations with other post-Soviet states and the problem of competing ‘near abroads’ for Russia and the West • The re-introduction of the Russian constitution as an appendix • An updated select bibliography • More focus on the challenges facing Russia in the twenty-first century Written in an accessible and lively style, this book is packed with detailed information on the central debates and issues in Russia’s difficult transformation. This makes it the best available textbook on the subject and essential reading for all those concerned with the fate of Russia, and with the future of international society. -

The Fate of the Russian State

The Fate of the Russian State THOMAS E. GRAHAM, JR. T he key to the resurrection and developmenl: of Russia lies today in the state- political sphere. Russia needs a strong state and it must have one," Russian president Vladimir Putin wrote in an essay entitled "Russia at the Turn of the Mil- lennium," released in the last week of December 1999, before he was elected pres- ident.) In a television interview shortly after he became acting president, he reit- erated that point: "I am absolutely convinced that we will not solve any problems, any economic or social problems, while the state is disintegrating"2 Putin has it right, for the defining feature of Russian developments for the past decade or more has not been progress or setbacks on the path of reform, the focus of so much Western commentary, but the fragmentation, degenera- tion, and erosion of state power. During that time, a fragile Russian state of uncertain legitimacy has grown even weaker as a consequence of deliberate, if misguided, policies, bitter and debilitating struggles for political power, and simple theft of state assets. The erosion of the state has reached such depths that the central state apparatus, or the center, as it is commonly called in Rus- sia, has little remaining capacity to mobilize resources for national purposes, either at home or abroad, while most regional and local governments lack the resources-and in some cases the desire-to govern effectively. The obvious weakness of the state has, not surprisingly, fueled fears about Russia's stabili- ty, integrity, and for some Russians, its survival. -

Boris Yeltsin and the Failure of Shock Therapy Christopher Huygen

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: Boris Yeltsin and the Failure of Shock Therapy Christopher Huygen Abstract The collapse of the Soviet Union created unprecedented dilemmas for the leaders of the new independent Russia. Shedding the communist past, Boris Yeltsin embarked on an ambitious program to reorganize Russia‟s political and economic systems. Known as „shock therapy,‟ Yeltsin advocated a rapid transition from state planning to a market economy while simultaneously introducing democracy to Russia. Expecting a short period of hardship as economic reforms opened Russia to world markets, followed by prolonged growth and prosperity, Yeltsin‟s societal upheaval left Russia a prostrate state, mired in a depression that left many longing for a return to socialism. This paper argues that the economic policies of shock therapy were an unmitigated failure. Four overarching factors will be analyzed to provide a foundational understanding of the social, economic, and international circumstances that made shock therapy‟s methods ineffective. Adopted before Russia was institutionally and politically prepared, the simultaneous transition to capitalism and democracy hindered the Russian state‟s ability to ensure a stable atmosphere to conduct business, while old guard communists obstructed progress by resisting radical change. Economic instability engendered by shock therapy reverberated throughout Russian society, creating political anxiety and lowering living standards that undermined the popular support crucial to the program‟s success. Shortsighted policies and inept privatization practices allowed a small conglomerate of business elites to gain control of Russia‟s most profitable industries, creating a class of oligarchs uninterested in reinvesting capital but skilled in circumventing Russia‟s tax laws. -

Russian Civil Society Symposium: SESSION REPORT Building Bridges 531 to the Future

Russian Civil Society Symposium: SESSION REPORT Building Bridges 531 to the Future Session 531 Salzburg, April 1 to 4, 2014 Russian Civil Society Symposium: Building Bridges Report author: Orysia Lutsevych to the Future with contributions from: Louise Hallman Thought paper authors: Polina Filippova, Svetlana Makovetskaya, Marina Pisklakova-Parker, Elena Topoleva-Soldunova, and Denis Volkov Photos: Ela Grieshaber Session 531 | Russian Civil Society Symposium: Building Bridges to the Future Table of Contents 05 Introduction 07 Perspectives on Russian Civil Society 12 Taking Measure of Russian Civil Society 16 Improving the Key Markers 18 Legal Matters 21 Resourcing the Sector 23 Building Bridges to... Where and When? 28 Specific Ideas for Change 31 Conclusion APPENDICES 32 I: Thought Papers 32 Polina Filippova, Director for Programmes and Donor Relations, CAF Russia 35 Svetlana Makovetskaya, Director, Grani Foundation 40 Marina Pisklakova-Parker, President, ANNA – Center for Prevention of Violence 44 Elena Topoleva-Soldunova, Director, Agency for Social Information 47 Denis Volkov, Analyst, Levada-Center 51 II: Features and Interviews 52: III: Session Participants 4 Introduction In April 2014, Salzburg Global Seminar, in cooperation with the Yeltsin Presidential Center and Yeltsin Foundation, hosted the Russian Civil Society Symposium: Building Bridges to the Future to address the challenges and opportunities currently facing civil society in Russia as a means to understand the needs and perspectives of Russian civil society groups and to consider new approaches to international civil society engagement with Russia. Since the 1990s, a more active and open civil society sector has developed across the Russian Federation. While civil society institutions and civic engagement in Russia are not new, the growth of the sector in recent years created hopes that Russian civil society could become the voice for a more effective democratic system, more efficient social services, and a check against corruption and centralized power. -

Interest Representation in Sverdlovsk and the Ascendancy of Regional Corporatism

Interest Representation in Sverdlovsk and the Ascendancy of Regional Corporatism LYNN D. NELSON AND IRINA Y. K UZES mong the most significant features of Russia’s current economic and politi- Acal transition that gained increasing prominence during the Gorbachev years has been the crystallization of corporate-administrative “clan” interests that evolved out of the preexisting Soviet system. Pressure for fundamental change intensified under Gorbachev as those who supported the preservation of social- ism were challenged by others favoring radical transformation. Moves away from central planning and state ownership in the economic sphere were accompanied with growing urgency by calls for democratization in the political sphere. Three distinct clusters of economic interests became clearly evident as this clash of per- spectives intensified during the 1980s. Conservatives were opposed by active pro- ponents of two contrasting visions for Russia. One interest grouping favored pri- vatization of state property and assets in a strongly corporatized context. Another advocated broad democratization and the building of institutions that would sup- port open market relations and provide a hospitable environment for new busi- ness ventures. This article focuses on Sverdlovsk in examining the dimensions of that contest at the regional level and in analyzing the basis for the ultimate suc- cess of corporate-administrative clan interests over their competitors.1 Early in the Gorbachev period, when the focus was predominantly on scien- tific and technological development and the improvement of Soviet production, Sverdlovsk oblast enterprises in the military-industrial complex seemed to be well suited to benefit. But with the policy shift that soon followed, it became clear that the prime beneficiaries of perestroika in Sverdlovsk would be those who con- trolled resources that could be competitive in the market. -

Playing-For-Power Layout 1

Playing for Power: The Agents Who Derailed the Soviet Union A CARNEGIE ETHICS STUDIO STUDY GUIDE A series of complex power plays brought down the Soviet Union. Mikhail Gorbachev’s long-term vision of change opened the door to a range of players, from democratic Russian reformers, to hardline Soviet communists, to conservative U.S. activists. These players competed for power and influence. The winners destroyed the Soviet Union and constructed a flawed democracy in its place. During this hour-long TV show, the Carnegie Ethics Studio introduces the characters who wrestled for control and sets out the lessons the world can take from this turbulent period. KEY PLAYERS RUSSIANS Political Actors ■ Mikhail Gorbachev • General secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union; head of state of the Soviet Union • Has a long-term vision of reform for the Soviet Union, which he begins to implement in the late 1980s with two programs: perestroika (reform) and glasnost (openness) • These reforms are soon seen by the left as an affront to communism and by the right as overly cautious; his policies of openness allow detractors to loudly voice their opinions ■ Boris Yeltsin • 1st president of the Russian Federation, 1991–1999 • Originally a Gorbachev supporter, Yeltsin emerged as a powerful political opponent • As president, becomes increasingly authoritarian and resigns on New Year’s Eve, 1999 ■ Alexander Urmanov • Yeltsin campaign manager • Attends democratization training run by Americans Paul Weyrich and Robert Krieble of the Free Congress Foundation -

Constructing a New Political Process: the Hegemonic Presidency and the Legislature, 28 J

UIC Law Review Volume 28 Issue 4 Article 3 Summer 1995 Constructing a New Political Process: The Hegemonic Presidency and the Legislature, 28 J. Marshall L. Rev. 787 (1995) John P. Willerton Alexsei A. Shulus Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Courts Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation John P. Willerton & Alexsei A. Shulus, Constructing a New Political Process: The Hegemonic Presidency and the Legislature, 28 J. Marshall L. Rev. 787 (1995) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol28/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTING A NEW POLITICAL PROCESS: THE HEGEMONIC PRESIDENCY AND THE LEGISLATURE JOHN P. WILLERTON* AND ALEKSEI A. SHULUS** INTRODUCTION Even a cursory examination of contemporary Russian politics would suggest to the observer continued institution building but confused governance at all levels of authority. Since the late 198- Os, the Russian political system, reflective of the broader society and economy, has been in a state of dynamic transition. Democra- tization and privatization have brought significant institutional and policy changes. Yet, important questions still linger as to the strength and durability of the current political arrangements. In the political realm, the most important struggles have revolved around new divisions of power and authority, as well as the delineation of new formal and informal rules which govern the behavior of decisionmakers.' Both Moscow and the locales have experienced these struggles. -

9 CALDWELL Legacy of German Reunification

The Legacy of German Reunification and the End of the Cold War on the Russian Identity: 1991-1995 Hayley Caldwell, University of Winnipeg German reunification was one of the most dramatic events in the collapse of the inferential communist system; however, it was by no means the final act. In the two years that followed the collapse of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the rest of the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe began abandoning the communist system, a process that by December 1991 came to an end with the complete dissolution of the USSR. Russia, however, as the largest and leading constituent of the Soviet Union, was arguably the most impaired by the chain of events as it became caught in a political impasse between dictatorship and democracy. Indeed, in light of Putin’s policies, it would seem that Russia has yet to overcome the legacy of Soviet authoritarianism. As Mikhail Gorbachev reflected in his memoirs in 2000, “Russia has not yet found a reliable, democratic, and truly free road of development; it is still burdened with authoritarianism. It has not yet found a road that would enrich its citizens, not ruin them, a road that ensure their political and damaged social rights, rather than restrict and limit them.”1 This essay will explore the path that Russia undertook between 1991 and 1995 following German Reunification to redefine itself politically, economically, militarily, and socially. It will conclude that during this period Russia proved much better at tearing down old institutions than in building new ones. From Dictatorship to Democracy: Brief Political Overview (1991-1995) Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985 and forever changed the face of the Soviet Union.