2.1 Transportation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To: Ashley Nguyen, Project Manager Metropolitan Transportation Commission Dear Ms

From: Terry Abrams Sent: Wednesday, June 24, 2015 5:05 PM To: MTC Info Subject: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Access Improvement Project To: Ashley Nguyen, Project Manager Metropolitan Transportation Commission Dear Ms. Nguyen and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, I am writing in support of adding the Richmond‐San Rafael Bridge Access Improvement Project to Plan Bay Area and to the 2015 Transportation Improvement Program. By prioritizing the re‐opening of the third lane on the Richmond‐San Rafael Bridge during peak evening commute hours, we will make a big difference in cutting traffic, reducing air pollution, and improving the quality of life in the North Bay. Thank you. Terry L. Abrams ABRAMS CONSULTING Management Consultants www.abramsconsulting.net 1 From: Jeff Alpert Sent: Wednesday, June 24, 2015 1:14 PM To: MTC Info Subject: Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Access Improvement Project To: Ashley Nguyen, Project Manager Metropolitan Transportation Commission Dear Ms. Nguyen and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, I am writing in support of adding the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge Access Improvement Project to Plan Bay Area and to the 2015 Transportation Improvement Program. By prioritizing the re-opening of the third lane on the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge during peak evening commute hours, we will make a big difference in cutting traffic, reducing air pollution, and improving the quality of life in the North Bay. Thank you. Jeffrey D.Alpert Managing Partner Milestone Trailer Leasing LLC Ph Cell 1 From: Shannon Appelcline Sent: Monday, July 20, 2015 11:57 AM To: MTC Info Cc: Subject: Support for Richmond/San Rafael Bridge Access Improvement Project I am writing to express my strong support for a bike lane across the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge. -

Cache Creek Annual Status Report 2010

CACHE CREEK ANNUAL STATUS REPORT 2010 Prepared by: Cache Creek Technical Advisory Committee: Dr. Eric Larsen, Geomorphologist, Chair Dr. Tim Horner, Hydrologist Erik Ringelberg, Riparian Biologist In Consultation with: Cindy Tuttle, Natural Resources Manager Heidi Tschudin, Program Consultant Vic Randall, Natural Resources Program Coordinator October 11, 2011 Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 4 1.2 ACCOMPLISHMENTS 4 1.3 SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS 6 1.4 NOTABLE VARIATIONS FROM PREVIOUS YEARS 6 1.5 RECOMMENDATIONS 6 1.5.1 Review of Prior Recommendations 6 1.5.2 New Recommendations 7 1.5.3 Channel Improvement Priorities 8 2 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY 9 2.1 RIVER FLOW AND STREAM HYDROGRAPHS 9 2.2 FLOOD MONITORING 11 2.3 SURFACE WATER QUALITY 11 2.4 METHYLMERCURY AND BIOACCUMULATION 27 2.5 GROUNDWATER LEVELS AND ANALYSIS 27 2.6 OVERVIEW OF GROUNDWATER AND SURFACE WATER PATTERNS BY REACH 30 3 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND CHANNEL HYDRAULICS 31 3.1 OVERVIEW 31 3.2 FLOOD CAPACITY 32 3.2.1 Flood Capacity Summary 32 3.2.2 Flood Capacity Analysis 32 3.3 BED MATERIAL SIZE 35 3.4 SEDIMENT TRANSPORT, SUSPENDED SEDIMENT, AND BED LOAD 35 3.5 ANNUAL SEDIMENT REPLENISHMENT 38 3.5.1 Annual Sediment Replenishment Analysis 41 3.6 ARMORING 43 3.7 MATERIAL EXTRACTED IN-CHANNEL 44 3.8 REACH OBSERVATIONS 44 3.8.1 Reach Overview 44 3.8.2 Reach Delineation 44 3.8.3 Reach “River Miles” 44 3.8.4 Longitudinal Water Surface Profiles (Slopes) By Reach 46 3.9 REACH BY REACH COMPARISONS 48 3.9.1 Capay Reach (RM 28.45 to 26.35) 48 3.9.2 Hungry -

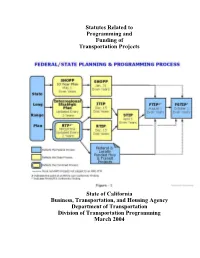

2004 Transportation Programming Statute Book

Statutes Related to Programming and Funding of Transportation Projects State of California Business, Transportation, and Housing Agency Department of Transportation Division of Transportation Programming March 2004 PREFACE STATUTES BOOK This book is a collection of statutes related to programming and funding of transportation projects. It is an auxiliary tool that is meant to provide easy access to current, relevant statutes. The 2004 edition of the Statutes Book incorporates all relevant legislation passed and signed into law up to January 1, 2004. All bills, with the exception of bills that are urgency statutes, become effective January 1st of the year following the end of the session. All bills passed in the 2003 legislative session become effective January 1, 2004. Bills that are urgency statutes become effective immediately upon signing into law by the Governor. At the end of certain sections of the book, you will find a row of asterisks. These asterisks indicate there is additional legislation in this chapter, however, it was omitted as it did not pertain to programming or funding. CALIFORNIA CODES California Law consists of 29 codes which cover the State Constitution and the California Statutes. As defined, California Statutes are bills that have been chaptered by the Secretary of State after the bill has passed through the Assembly and Senate and subsequently signed by the Governor, or becomes law without the Governor’s signature. INTERNET ACCESS The Programming Statutes Book is accessible on the internet at the following address: http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/transprog/reports.htm The Legislative Counsel of California is required by law to maintain the World Wide Web (www) site where the complete California Codes are located. -

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide

Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide A Complete Compendium Of RV Dump Stations Across The USA Publiished By: Covenant Publishing LLC 1201 N Orange St. Suite 7003 Wilmington, DE 19801 Copyrighted Material Copyright 2010 Covenant Publishing. All rights reserved worldwide. Ultimate RV Dump Station Guide Page 2 Contents New Mexico ............................................................... 87 New York .................................................................... 89 Introduction ................................................................. 3 North Carolina ........................................................... 91 Alabama ........................................................................ 5 North Dakota ............................................................. 93 Alaska ............................................................................ 8 Ohio ............................................................................ 95 Arizona ......................................................................... 9 Oklahoma ................................................................... 98 Arkansas ..................................................................... 13 Oregon ...................................................................... 100 California .................................................................... 15 Pennsylvania ............................................................ 104 Colorado ..................................................................... 23 Rhode Island ........................................................... -

PW Case 2011-021

STATE OF CALIFORNIA GAVIN NEWSOM, Governor DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS Office of the Director 1515 Clay Street, 17th Floor Oakland, CA 94612 Tel: (510) 286-7087 Fax: (510) 622-3265 To All Interested Parties: Re: Public Works Case No. 2011-021 Westrust Nut Tree Project City of Vacaville and Vacaville Redevelopment Agency The Decision on Administrative Appeal, dated June 25, 2015, in PW 2011-021, Westrust Nut Tree Project – City of Vacaville and Vacaville Redevelopment Agency, was affirmed in an unpublished First District Court of Appeal opinion issued on March 15, 2019. (See Nut Tree Holdings, LLC v. Baker (Mar. 15, 2019, A150087) 2019 WL 1219454 [nonpub. opn.].) STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS DECISION ON ADMINISTRATIVE APPEAL RE: PUBLIC WORKS CASE NO. 2011-021 WESTRUST NUT TREE PROJECT CITY OF VACAVILLE AND VACAVILLE REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY I. INTRODUCTION On August 8, 2014, the Director of the Department of Industrial Relations (the “Director”) issued a public works coverage determination (the “Determination”) in the above- referenced matter finding that the Westrust Nut Tree Project was funded in part with public monies and is therefore a public work subject to the California prevailing wage requirements. On September 4, 2014, Nut Tree Holdings, LLC (“Nut Tree Holdings”) timely filed a notice of appeal of the Determination (“Appeal”), which included a request for a hearing. All interested parties were thereafter given an opportunity to provide legal argument and any additional supporting evidence. Nut Tree Holdings filed opening and reply submissions in support of the Appeal, and the Northern California Carpenters Regional Council (“NCCRC”) filed an opposition.1 The Director has sole discretion to decide whether to hold a hearing. -

Options for a Bay Area Transportation Network Manager

Governing Transit Seamlessly: Options for a Bay Area Transportation Network Manager A report by Seamless Bay Area April 2021 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: Poor Outcomes, Root Causes, and Solutions 11 Poor outcomes 11 Root causes 13 Solutions 16 Increased investment 16 Transit-supportive land uses 16 Reformed transportation institutions 16 Chapter 3: Network Manager Key Considerations & Conceptual Models 18 Functions a network manager should oversee 18 Conceptual models of network management 19 Geographical coverage considerations 20 Governing board considerations 21 Approach to geographical representation on boards 22 Relationship to existing institutions 24 Chapter 4: Network Manager Alternative Options 26 Option A: Altered MTC Network Manager 27 Option B: Regional Transit Agency Network Manager 31 Option C: Universal Transit Agency Network Manager 38 Option D: Enhanced Executive Board 43 Chapter 5: Evaluation 46 Chapter 6: Conclusions & Next Steps 49 Conclusions 49 Next Steps 51 Acknowledgments 53 Seamless Bay Area Board 53 2 Executive Summary “If you want to get people to do something, make it easy,” Nobel-prize winning behavioral economist Richard Thaler oen says. “Remove the obstacles." Seamless transit is about making transit easy so more people use it - giving people from all backgrounds true freedom of movement to live their fullest lives. It’s the reason why Principle #1 in the Seamless Transit Principles, endorsed by dozens of organizations and cities, is Run all Bay Area transit as one easy-to-use system. Easy-to-use transit isn’t a luxury that only matters to some people - transit that is easy is fundamentally also accessible, usable, and equitable. -

Redevelopment Agency of the City of Oakland Broadway/Macarthur/San Pablo Project Tax Allocation Bonds, Series

NEW ISSUE-BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: Moody’s: Aaa (Baa2 underlying) S&P: AAA (BBB+ underlying) (See “Ratings” herein) In the opinion of Jones Hall, A Professional Law Corporation, San Francisco, Bond Counsel, subject, however to certain qualifications, under existing law, the interest on the Series 2006C-TE Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes and such interest is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations, although for the purpose of computing the alternative minimum tax imposed on certain corporations, such interest is taken into account in determining certain income and earnings. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Series 2006C-TE Bonds and the Series 2006C-T Bonds is exempt from California personal income taxes. Interest on the Series 2006C-T Bonds is subject to all applicable federal income taxation. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. $4,945,000 $12,325,000 REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY OF THE CITY OF OAKLAND CITY OF OAKLAND BROADWAY/MACARTHUR/ SAN PABLO BROADWAY/MACARTHUR/ SAN PABLO REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT TAX ALLOCATION BONDS TAX ALLOCATION BONDS SERIES 2006C-TE SERIES 2006C-T (FEDERALLY TAXABLE) Dated: Date of Delivery Due: September 1, as shown on inside cover page This cover page contains certain information for quick reference only. It is not a summary of this issue. Investors are advised to read the entire Official Statement to obtain information essential to the making -

Directions from Meadowood to Sacramento Airport Daly City

Directions to Meadowood Directions to Meadowood Directions to Meadowood Middletown Directions to Meadowood Directions to Meadowood from San Francisco International from San Francisco International from San Francisco International from Sacramento Airport from Oakland Airport Geyserville Airport via the Golden Gate Bridge Airport via the Golden Gate Bridge Airport via the Bay Bridge Take Interstate 5 south approximately 5 miles. Take From Oakland Airport, follow all signs to Interstate 880 and Santa Rosa Calistoga the Interstate 80 exit toward San Francisco, west. north. Continue on Interstate 880 north for 8 miles Take Highway 101 north staying to the left at fork. Travel 1 Take Highway 101 north, (staying to the right) toward St. Helena Winters Continue on Interstate 80 through Fairfield. Take the to Interstate 80 east. Take Interstate 80 east toward mile taking Interstate 380 west toward Interstate 280 (San San Francisco. Travel 6 miles. Highway 101 then merges Highway 12 exit toward Napa. Continue on Highway 12 Berkeley/Vallejo/Sacramento for approximately 25 miles, Take Highway 101 north staying left at the fork. Travel 1 mile Santa Rosa Bruno). Travel 1 mile then take I-280 north toward San into Interstate 80. Follow signs to Bay Bridge/Oakland. Rutherford To approximately 6 miles to Highway 29. Turn right following all signs to Vallejo. You will cross the Carquinez Francisco. Take Highway 1 toward 19th Ave./Golden Gate taking Interstate 380 west toward Interstate 280 (San Bruno). Cross Bay Bridge and stay in left lanes following signs to Sacramento (north), and continue 25 miles through the towns of Bridge, where you will need to pay a $5 toll. -

1963 1963 the the of of of of Description Description

e y ~ 'rte ~ 4 ~ ~~~. ~ ~ ~L +i's 's' ~ *" a~t,y'" J ^ ,..,T+s d az' ~ 8a•. ~r ~ ~Y. r~ ,~ } ~„ ~"' y s'~ ~- ~- N ~, 4 r ~ ts~ 0 ~ i~° e~ ~" t ~ y ~ _ ~ ~ y ^: *} ~ }t. ~ `/ ~ 6~ Y ~p S d~Y R" vW # ' `i ti r n' ke~s ~ J ~ ~ ~~ +3 ~ y t ~r x. t' ~ ~~ ~i _ ~.~y ~g x ,. 9~ :~ ~ x aaa+ra.. "' ~$ .;~w~.v 'Y~1se~n ~+~.~-*a fir;.: ~. ,... §~~`" u, a ., .. ~.: w Letters of Transmittal December 9, 1963 December 9, 1963 JOHN ERRECA EDMUND G. BROWN Director of Public Works Governor of California State of California My dear Governor: Dear Sir: The 17th Annual Report of the Division of Highways, Depart- In compliance with Section 143 of the Streets and Highways ment of Public Works, which I am pleased to submit to you, Code, the 17th Annual Report of the Division of Highways for presents a broad picture of the state highway program during the fiscal year ending June 30, 1963, is submitted herewith fiscal year 1962-63. It describes the steady progress in planning for your approval and transmittal to Governor Edmund G. and constructing today for tomorrow's transportation needs, as Brown. well as the activities of the division's various units. The report contains information on the construction program Your attention is invited to the comments contained in the through the end of 1963 and a description of the projects in enclosed letter of transmittal from the State Highway Engineer the budget for fiscal year 1964-65 which the California High- regarding progress on the interstate system and on the network way Commission adopted in October. -

Iowa City a Collection of Curious Communities Destination Planner Welcome Contents

IOWA CITY A COLLECTION OF CURIOUS COMMUNITIES DESTINATION PLANNER WELCOME CONTENTS AN EASTERN IOWA WELCOME 4 WHY IOWA CITY Thank you for considering the Iowa City area for your next event! I have been very fortunate 5 TRAVEL to help lead the destination marketing efforts of our community for almost 18 years. I am as honored today as I was when first provided this opportunity and the reasons are clear. Iowa City, 6 MEETING SERVICES Coralville, North Liberty, Johnson County and the University of Iowa make up a very special place. We are a cultured and diverse community. A place where critical discourse is truly revered. 8 MEETING FACILITIES Collaboration is a way of life in this community where hard work is honored. 20 ADDITIONAL HOTELS Our team here at the Convention & Visitors Bureau along with our truly fantastic community partners will settle for nothing less than providing you and your group an exceptional experience. As Iowans, we are, by nature, an incredibly generous and inviting people and it is our goal that 38 ALTERNATE MEETING VENUES you return home in agreement. We look forward to the opportunity to serve and please don’t hesitate to reach out directly if our team can be of more assistance. 40 DINING ESTABLISHMENTS 41 AREA MAP Josh Schamberger, President 43 CONTACT INFORMATION OUR CURIOUS COMMUNITIES TESTIMONIALS Iowa City is a center for art, culture, education and recreation. It boasts a vibrant, bike- and pedestrian-friendly downtown with many bars, restaurants, boutique shops a blend of new urban and historic neighborhoods. Home of the University of Iowa, world class health care and a rich literary heritage, the city continues to be recognized on a national scale. -

ENTRIX Report Template

DRAFT Environmental Impact Report for the Granite Esparto Mining and Reclamation Project Long-Term Mining Permit Application Zone File Number: 2007-071 December 2009 SCH Number: 2009022036 Prepared by Prepared for COUNTY OF YOLO YOLO COUNTY PARKS AND RESOURCES DEPARTMENT NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY AND PUBLIC HEARING for the DRAFT PROGRAM ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT on the GRANITE ESPARTO MINING AND RECLAMATION PROJECT DATE: December 11, 2009 TO: Interested Agencies and Individuals FROM: Yolo County Parks and Resources Department The Draft Program Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) (SCH #2009022036) for the Granite Esparto Mining and Reclamation Project is now available for review. Public comment on this document is invited for a 46-day period extending from December 14, 2009 through January 28, 2010. More information is provided herein. The property is located on 390 acres in central Yolo County, adjoining County Road 87, approximately one mile north of the town of Esparto. The project site is comprised of two adjacent parcels, APN 048-220-022 (286.4 acres) on the north and APN 048-220-015 (103.6 acres) on the south. The site encompasses the active channel of Cache Creek and a portion of the relatively flat terrace north of the creek. Aggregate mining and processing is proposed on 313 acres of the 390-acre total. The applicant, Granite Construction Company, proposes the mining of about 30 million tons (26.1 million tons sold maximum) of aggregate over a 30-year period at a rate of about one million tons per year (870,000 tons sold maximum). -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate.