PW Case 2011-021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cache Creek Annual Status Report 2010

CACHE CREEK ANNUAL STATUS REPORT 2010 Prepared by: Cache Creek Technical Advisory Committee: Dr. Eric Larsen, Geomorphologist, Chair Dr. Tim Horner, Hydrologist Erik Ringelberg, Riparian Biologist In Consultation with: Cindy Tuttle, Natural Resources Manager Heidi Tschudin, Program Consultant Vic Randall, Natural Resources Program Coordinator October 11, 2011 Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 4 1.2 ACCOMPLISHMENTS 4 1.3 SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS 6 1.4 NOTABLE VARIATIONS FROM PREVIOUS YEARS 6 1.5 RECOMMENDATIONS 6 1.5.1 Review of Prior Recommendations 6 1.5.2 New Recommendations 7 1.5.3 Channel Improvement Priorities 8 2 HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY 9 2.1 RIVER FLOW AND STREAM HYDROGRAPHS 9 2.2 FLOOD MONITORING 11 2.3 SURFACE WATER QUALITY 11 2.4 METHYLMERCURY AND BIOACCUMULATION 27 2.5 GROUNDWATER LEVELS AND ANALYSIS 27 2.6 OVERVIEW OF GROUNDWATER AND SURFACE WATER PATTERNS BY REACH 30 3 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND CHANNEL HYDRAULICS 31 3.1 OVERVIEW 31 3.2 FLOOD CAPACITY 32 3.2.1 Flood Capacity Summary 32 3.2.2 Flood Capacity Analysis 32 3.3 BED MATERIAL SIZE 35 3.4 SEDIMENT TRANSPORT, SUSPENDED SEDIMENT, AND BED LOAD 35 3.5 ANNUAL SEDIMENT REPLENISHMENT 38 3.5.1 Annual Sediment Replenishment Analysis 41 3.6 ARMORING 43 3.7 MATERIAL EXTRACTED IN-CHANNEL 44 3.8 REACH OBSERVATIONS 44 3.8.1 Reach Overview 44 3.8.2 Reach Delineation 44 3.8.3 Reach “River Miles” 44 3.8.4 Longitudinal Water Surface Profiles (Slopes) By Reach 46 3.9 REACH BY REACH COMPARISONS 48 3.9.1 Capay Reach (RM 28.45 to 26.35) 48 3.9.2 Hungry -

ENTRIX Report Template

DRAFT Environmental Impact Report for the Granite Esparto Mining and Reclamation Project Long-Term Mining Permit Application Zone File Number: 2007-071 December 2009 SCH Number: 2009022036 Prepared by Prepared for COUNTY OF YOLO YOLO COUNTY PARKS AND RESOURCES DEPARTMENT NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY AND PUBLIC HEARING for the DRAFT PROGRAM ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT on the GRANITE ESPARTO MINING AND RECLAMATION PROJECT DATE: December 11, 2009 TO: Interested Agencies and Individuals FROM: Yolo County Parks and Resources Department The Draft Program Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) (SCH #2009022036) for the Granite Esparto Mining and Reclamation Project is now available for review. Public comment on this document is invited for a 46-day period extending from December 14, 2009 through January 28, 2010. More information is provided herein. The property is located on 390 acres in central Yolo County, adjoining County Road 87, approximately one mile north of the town of Esparto. The project site is comprised of two adjacent parcels, APN 048-220-022 (286.4 acres) on the north and APN 048-220-015 (103.6 acres) on the south. The site encompasses the active channel of Cache Creek and a portion of the relatively flat terrace north of the creek. Aggregate mining and processing is proposed on 313 acres of the 390-acre total. The applicant, Granite Construction Company, proposes the mining of about 30 million tons (26.1 million tons sold maximum) of aggregate over a 30-year period at a rate of about one million tons per year (870,000 tons sold maximum). -

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 233/Monday, December 4, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 233 / Monday, December 4, 2000 / Notices 75771 2 departures. No more than one slot DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION In notice document 00±29918 exemption time may be selected in any appearing in the issue of Wednesday, hour. In this round each carrier may Federal Aviation Administration November 22, 2000, under select one slot exemption time in each SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION, in the first RTCA Future Flight Data Collection hour without regard to whether a slot is column, in the fifteenth line, the date Committee available in that hour. the FAA will approve or disapprove the application, in whole or part, no later d. In the second and third rounds, Pursuant to section 10(a)(2) of the than should read ``March 15, 2001''. only carriers providing service to small Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. hub and nonhub airports may L. 92±463, 5 U.S.C., Appendix 2), notice FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: participate. Each carrier may select up is hereby given for the Future Flight Patrick Vaught, Program Manager, FAA/ to 2 slot exemption times, one arrival Data Collection Committee meeting to Airports District Office, 100 West Cross and one departure in each round. No be held January 11, 2000, starting at 9 Street, Suite B, Jackson, MS 39208± carrier may select more than 4 a.m. This meeting will be held at RTCA, 2307, 601±664±9885. exemption slot times in rounds 2 and 3. 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW., Suite Issued in Jackson, Mississippi on 1020, Washington, DC, 20036. November 24, 2000. e. Beginning with the fourth round, The agenda will include: (1) Welcome all eligible carriers may participate. -

Annual Report Issue

t ,~, ~'i - annual report issue ~.. .,; ~~~ ~~ ~ \ ~ _ ~ , -w,A ~ ~ w Letters of Transmitta December 19, 1966 December 20, 1966 MR. JOHN ERRECA EDMUND G. BROWN Director of Public Works Governor of CaPifornia State of California My Dear Governor: Sir: Dear am pleased to submit to you the 20th Annual Report of am submitting herewith for your approval and transmittal the Division of Highways. to the Governor, the 20th Annual Reporf of the Division of Done in a shorter, more popularized form, this year's report, Highways for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1966. The report believe, still presents the highlights of how the nation's most was prepared in compliance with Section 143 of the Streets populous state is meeting and overcoming the challenge of an and Highways Code. ever increasing traffic demand by moving ahead in the con- As before, the text portion of the report with accompanying struction of what is undoub#edly the world's finest highway and illustrations is being published as the November—December freeway system. issue of Ca`ifornia Highways and Public Works magazine. De- Totaling some 14,215 miles at the end of the fiscal year, tailed financial statements, tables and contract statistics will the state highway system included 1,945 miles of freeways. appear in a supplement which will be available to anyone on Though comprising only 2 percent of the state's paved driving request. surfaces, these freeways carry a quarter of the state's traffic Although a large portion of the past fiscal year's highway load and have proved three times as safe to drive upon as program continued to be devoted to completion of the inter- conventional highways. -

Vanden Meadows Specific Plan and Development Project (“Project”) in the City of Vacaville, California

APPENDIX O TRAFFIC IMPACT STUDY Traffic Study Report for the Vanden Meadows Specific Plan & Development Project November 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................. 1 B. PROJECT LOCATION ................................................................................................. 1 C. PROJECT STUDY AREA ............................................................................................. 1 II. ASSUMPTIONS AND METHODOLOGY 5 A. TRAFFIC MODEL ...................................................................................................... 5 B. PLANNED TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENTS .......................................................... 5 C. GENERAL PLAN CONSISTENCY ................................................................................ 6 D. ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................... 6 E. STANDARDS OF SIGNIFICANCE ................................................................................. 7 F. ANALYSIS SCENARIOS ............................................................................................. 8 III. PROJECT DESCRIPTION, TRIP GENRATION AND GENERAL PLAN 11 A. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................... 11 B. PROJECTED PROJECT TRIP GENERATION ................................................................ 11 C. GENERAL PLAN AND REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION PLAN -

1/ Introduction

YOLO COUNTY 2021—2029 Housing Element Public Review Draft June 2021 Prepared by: 6TH CYCLE HOUSING ELEMENT HOUSING PLAN Table of Contents II INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................1 Contents ...........................................................................................................................1 Community Overview ........................................................................................................2 III COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION ............................................................................................6 Public Outreach ................................................................................................................6 Approach to Public Outreach .................................................................................6 Notification of Community Participation Opportunities ...........................................7 Virtual Housing Workshop and Survey ..................................................................2 Housing Issues and Priorities Survey Results .......................................................3 Stakeholders Outreach and Survey Results ..........................................................6 Public Review Draft Housing Element ...............................................................................9 Planning Commission ............................................................................................9 Board of Supervisors ...........................................................................................10 -

Draft NHMRR Federal Register Notice

State: California State Agency: CA Highway Patrol FMCSA: CA FMCSA Field Office POC: Tian-Ting Shih FMCSA POC: CA Motor Carrier Division Administrator Address: Commercial Vehicle Section Address: 1325 J Street, Suite 1540 P.O. Box 942898 Sacramento, CA 95814 Sacramento, CA 94298-0001 Phone: (916) 843-3400 Phone: (916) 930-2760 Fax: (916) 322-3154 Fax: (916) 930-2778 Web Address: www.chp.ca.gov California – Restricted HM routes Desig- Route Restriction(s) nation Route Description City County Order (0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,i) Date 10/28/92 A No person shall drive or permit the driving of 1 any vehicle transporting commodities listed in Section 13 CCR 1150 upon any highway not designated by this article. For pickup and delivery not over designated routes, the route selected must be the shortest-distance route from the pickup location to the nearest designated route entry location, and the shortest-distance route to the delivery location from the nearest designated route exit location. 01/01/95 B State 75 [Coronado Toll Bridge] from Mile Post San Diego San Diego 1,2,3,4 20.28 to Mile Post R22.26 Junction 5 [San Diego County] No flammables/corrosives or explosives on Coronado Bay Bridge (otherwise route is terminal access) 06/29/00 C Sepulveda Blvd. [tunnel] from Interstate Los Angeles Los Angeles 1,2,3,4,5,6,8 105/Imperial Highway to W. Century Blvd. [Restriction for Tank Vehicles] 10/28/92 D State 118 from State 232 [Oxnard] to Los 1 Angeles [western county line] 01/01/95 E State 154 from State 246 [MP 8.11- Santa Ynez] Santa Barbara 0 to US 101 [near Los Olivos] No hazardous materials or waste except pickup and delivery (otherwise, from R8.11 to R9.97 is Terminal Access and from R9.97 to 32.29 is California Legal) 1968 F Monterey Traffic Underpass from Washington Monterey Monterey 0 St. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-215 (Salt Lake City, Utah) Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 215 (Salt Lake City, Utah) Aktiengesellschaft Trial, Nuremberg, I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-225 (Colo.) Germany, 1947-1948 USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 225 (Colo.) Subsequent proceedings, Nuremberg War Corridor (Ill.) I-244 (Tulsa, Okla.) Crime Trials, case no. 6 I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 244 (Tulsa, Okla.) BT Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-255 (Ill. and Mo.) Germany, 1946-1949 I-5 USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-H-3 (Hawaii) USE Interstate 5 I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) USE Interstate H-3 (Hawaii) I-8 (Ariz. and Calif.) USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-hadja (African people) USE Interstate 8 (Ariz. and Calif.) I-270 (Md.) USE Kasanga (African people) I-10 USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I Ho Yüan (Beijing, China) USE Interstate 10 I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE Interstate 15 I-291 (Conn.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 291 (Conn.) I-hsing ware USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-394 (Minn.) USE Yixing ware I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-K'a-wan Hsi (Taiwan) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Qijiawan River (Taiwan) I-17 USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE Interstate 17 I-405 (Wash.) UF Gilbertese I-19 (Ariz.) USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Interstate 19 (Ariz.) I-470 (Ohio and W. -

Visitor's Guide

2012-13 VISITOR’S GUIDE Department of Intercollegiate Athletics 1801 East Cotati Ave. Rohnert Park, CA 94928 VISITOR’S GUIDE VISITOR’S GUIDE GENERAL INFORMATION Sonoma State University occupies 247 acres in the beautiful wine country of Sonoma County, in Northern California. Located at the foot of the Sonoma hills, the campus is just an hour’s drive north of San Francisco and 40 minutes away from the Pacific Ocean. Sonoma State University is dedicated to the liberal arts and sciences and is known for active use of technol- ogy. As California’s premier public undergraduate institution, SSU has a commitment to graduating students who have the ability to think critically and ethically and can effectively use information technology. Our relatively small campus of 8,000 allows for close faculty-student interaction. Sonoma State University is deeply committed to the teaching and learning of liberal arts and sciences. And we are proud that we have continued to develop a reputation for excellence. We were recently invited to represent California as a member of the nationwide Council of Public Liberal Arts Colleges, a group of colleg- es dedicated to promoting the values of superior undergraduate education in a public college setting. We think this selection is a testament to our strengths and our mission: enlightening students, growing minds, and enriching lives. The six academic schools include the Arts and Humanities, Business and Economics, Education, Extended Education, Science and Technology, and Social Sciences. All six schools are home -

Draft NHMRR Federal Register Notice

State: California State Agency: CA Highway Patrol POC: Tian-Ting Shih Address: Commercial Vehicle Section P.O. Box 942898 Sacramento, CA 94298-0001 Phone: (916) 843-3400 Fax: (916) 322-3154 Web Address: www.chp.ca.gov California – Restricted HM routes Desig- Route Restriction(s) nation Route Description City County Order (0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,i) Date 10/28/92 A No person shall drive or permit the driving of 1 any vehicle transporting commodities listed in Section 13 CCR 1150 upon any highway not designated by this article. For pickup and delivery not over designated routes, the route selected must be the shortest-distance route from the pickup location to the nearest designated route entry location, and the shortest-distance route to the delivery location from the nearest designated route exit location. 01/01/95 B State 75 [Coronado Toll Bridge] from Mile Post San Diego San Diego 1,2,3,4 20.28 to Mile Post R22.26 Junction 5 [San Diego County] No flammables/corrosives or explosives on Coronado Bay Bridge (otherwise route is terminal access) 06/29/00 C Sepulveda Blvd. [tunnel] from Interstate Los Angeles Los Angeles 1,2,3,4,5,6,8 105/Imperial Highway to W. Century Blvd. [Restriction for Tank Vehicles] 10/28/92 D State 118 from State 232 [Oxnard] to Los 1 Angeles [western county line] 01/01/95 E State 154 from State 246 [MP 8.11- Santa Ynez] Santa Barbara 0 to US 101 [near Los Olivos] No hazardous materials or waste except pickup and delivery (otherwise, from R8.11 to R9.97 is Terminal Access and from R9.97 to 32.29 is California Legal) 1968 F Monterey Traffic Underpass from Washington Monterey Monterey 0 St. -

F-5: Historical/Architectural Survey Report

F-5: Historical/Architectural Survey Report April 2009 PG&E Line 406/407 Natural Gas Pipeline Draft EIR HISTORIC ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY REPORT AND FINDING OF EFFECT FOR THE PG&E LINES 406 AND 407 PIPELINE PROJECT IN PLACER, SACRAMENTO, SUTTER AND YOLO COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA October 2008 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS The Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) is proposing to construct and operate multiple natural gas transmission pipelines and a new distribution feeder main that cross California’s Central Valley in Placer, Sacramento, Sutter and Yolo counties (see Appendix A, Maps 1 and 2). There are also eight alternative route areas (see Appendix A, Map 3). The PG&E Lines 406 and 407 Pipeline Project (Project) would run below ground, from Esparto in Yolo county to the west, then east to Roseville in Placer county. Project construction would involve a combination of conventional trenching, horizontal directional drilling (HDD) and hammer boring. The California State Lands Commission (CSLC) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) are co-lead agencies for the Project. There is Federal involvement because the pipelines are proposed to go through wetland areas and therefore section 404 permitting is required. This Historic Architectural Survey Report (HASR) was prepared so that the USACE can comply with section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (36 CFR Part 800 et seq.). Properties located within the Project area that are greater than 45 years of age were identified. These previously unevaluated properties were evaluated for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). This document also addressed compliance under California state law for the proposed Project in accordance with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) guidelines at Title 14 California Code of Regulations (CCR) §15064.5 and Public Resources Code (PRC) 5024, using the criteria for inclusion in the California Register of Historical Resources (CRHR). -

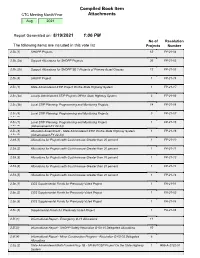

FINAL-VIPER Votelist Aug-2021

Compiled Book Item CTC Meeting Month/Year Attachments Aug 2021 Report Generated on: 8/19/2021 1:06 PM No of Resolution The following items are included in this vote list Projects Number 2.5b.(1) SHOPP Projects 62 FP-21-04 2.5b.(2a) Support Allocations for SHOPP Projects 26 FP-21-05 2.5b.(2b) Support Allocations for SHOPP SB 1 Projects of Primary Asset Classes 12 FP-21-05 2.5b.(4) SHOPP Project 1 FP-21-16 2.5c.(1) State Administered STIP Project On the State Highway System 1 FP-21-17 2.5c.(3a) Locally Administered STIP Projects Off the State Highway System 3 FP-21-06 2.5c.(3b) Local STIP Planning, Programming and Monitoring Projects 14 FP-21-06 2.5c.(4) Local STIP Planning, Programming and Monitoring Projects 5 FP-21-07 2.5v.(1) 2.5c.(7) Local STIP Planning, Programming and Monitoring Project 1 FP-21-15 2.5v.(2) (Advancement FY 22-23) 2.5c.(8) Allocation Amendment - State Administered STIP On the State Highway System 1 FP-21-18 2.5v.(5) (Advancement FY 22-23) 2.5d.(1) Allocations for Projects with Cost Increase Greater than 20 percent 1 FP-21-10 2.5d.(2) Allocations for Projects with Cost Increase Greater than 20 percent 1 FP-21-11 2.5d.(3) Allocations for Projects with Cost Increase Greater than 20 percent 1 FP-21-12 2.5d.(4) Allocations for Projects with Cost Increase Greater than 20 percent 1 FP-21-13 2.5d.(5) Allocations for Projects with Cost Increase Greater than 20 percent 1 FP-21-14 2.5e.(1) COS Supplemental Funds for Previously Voted Project 1 FA-21-01 2.5e.(2) COS Supplemental Funds for Previously Voted Project 1 FA-21-02 2.5e.(3)