Gender Equality in the Political Sphere of Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T C K a P R (E F C Bc): C P R

ELECTRUM * Vol. 23 (2016): 25–49 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.16.002.5821 www.ejournals.eu/electrum T C K A P R (E F C BC): C P R S1 Christian Körner Universität Bern For Andreas Mehl, with deep gratitude Abstract: At the end of the eighth century, Cyprus came under Assyrian control. For the follow- ing four centuries, the Cypriot monarchs were confronted with the power of the Near Eastern empires. This essay focuses on the relations between the Cypriot kings and the Near Eastern Great Kings from the eighth to the fourth century BC. To understand these relations, two theoretical concepts are applied: the centre-periphery model and the concept of suzerainty. From the central perspective of the Assyrian and Persian empires, Cyprus was situated on the western periphery. Therefore, the local governing traditions were respected by the Assyrian and Persian masters, as long as the petty kings fulfi lled their duties by paying tributes and providing military support when requested to do so. The personal relationship between the Cypriot kings and their masters can best be described as one of suzerainty, where the rulers submitted to a superior ruler, but still retained some autonomy. This relationship was far from being stable, which could lead to manifold mis- understandings between centre and periphery. In this essay, the ways in which suzerainty worked are discussed using several examples of the relations between Cypriot kings and their masters. Key words: Assyria, Persia, Cyprus, Cypriot kings. At the end of the fourth century BC, all the Cypriot kingdoms vanished during the wars of Alexander’s successors Ptolemy and Antigonus, who struggled for control of the is- land. -

Europeanisation and 'Internalised' Conflicts: the Case of Cyprus

Europeanisation and 'Internalised' Conflicts: The Case of Cyprus George Kyris GreeSE Paper No. 84 Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe APRIL 2014 All views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Hellenic Observatory or the LSE © George Kyris _ TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT __________________________________________________________ iii 1. Introduction _____________________________________________________ 1 2. Europeanisation and Regional Conflicts: Inside and Outside of the European Union_______________________________________________________________ 3 3. Greek Cypriots: The State Within ____________________________________ 8 4. Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots: The End of Credible Conditionality? ______ 12 5. Conclusion _____________________________________________________ 17 References _________________________________________________________ 21 ii Europeanisation and 'Internalised' Conflicts: The Case of Cyprus George Kyris # ABSTRACT This article investigates the role of the EU in conflict resolution, taking Cyprus as a case of an 'internalised' conflict, whereby a side of the dispute has become a member state (Greek-Cypriots), while the rest of actors (Turkey, Turkish Cypriots) remain outside but are still developing relations to the EU. In exploring the impact of the EU on Greek Cypriot, Turkish Cypriot and Turkish policies towards the dispute, this work engages with the Europeanisation debate. The argument advanced is that internalisation of the conflict limits the ability of the EU to act in the dispute and triggers inflexible policies, which are counterproductive to resolution. This work contributes to the Europeanisation discussion and the impact of the EU on domestic policies, especially in conflict situations. With a series of conflicts in the European periphery but also disputes within the EU (e.g. separatists tensions), this is an important contribution to the understudied topic of 'internalised conflicts'. -

Cyprus News Brussels Edition

CYPRUS NEWS BRUSSELS EDITION Monthly Bulletin April 2011 Issue No. 14 Covering the period 1-31 March Christoas tables EU leaders focus on economy and Libya new proposal in Union of the European Council Cyprus negotiations President Demetris Christoas and Turkish Cypriot leader Dervis Eroglu held further sessions of UN-sponsored negotiations on a Cyprus settlement in Nicosia on 4, 9, 18, 23 and 30 March. In a new initiative on 23 March, President Christoas proposed that a census should be held in the Government-controlled and Turkish-occupied areas of Cyprus, under the auspices of the UN. Responding to the call by UN Secretary General Ban Ki- moon for practical steps to give impetus to the negotiating process, the President Ŗ$TWUUGNUYGNEQOG2TGUKFGPV%JTKUVQſCUKUITGGVGFD[*GTOCP8CP4QORW[VJG'WTQRGCP%QWPEKN2TGUKFGPV explained that the results of an independent The adoption of a comprehensive package census would provide essential data for The European Council also adopted of measures to respond to the global the Euro Plus Pact, as agreed by the euro the resolution of the dicult issue of the nancial crisis was the central theme of the large number of settlers brought illegally area Heads of State and Government on 11 Spring European Council on 24-25 March. March. Speaking on 11 March, President into the occupied area from Turkey since Speaking after the summit, President Christoas welcomed the goals expressed the Turkish invasion in 1974. However, the Christoas said that the package of measures in the Pact, stating that it is important that proposal elicited no positive response from was the result of long consultations during member states retain the power to decide Mr Eroglu. -

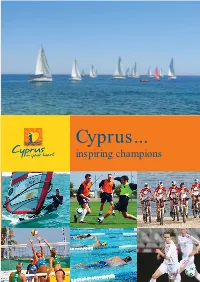

Visitcyprus.Com

Cyprus... inspiring champions “I found this training camp ideal. I must compliment the organisation and all involved for an excellent stay again. I highly recommend all professional teams to come to the island…” Gery Vink, Coach of Jong Ajax 1 Sports Tourism in Cyprus There are many reasons why athletes and sports lovers are drawn to the beautiful island of Cyprus… There’s the exceptional climate, the range of up-to-date sports facilities, the high-quality service industry, and the short travel times between city, sea and mountains. Cyprus offers a wide choice of sports facilities. From gyms Many international sports bodies have already recognized Cyprus to training grounds, from Olympic swimming pools to mountain as the ideal training destination. And it’s easy to see why National biking routes, there’s everything the modern sportsman or Olympic Committees from a number of countries have chosen woman could ask for. Cyprus as their pre-Olympic Games training destination. One of the world’s favourite holiday destinations, Cyprus also Medical care in Cyprus is of the highest standard, combining has an impressive choice of accommodation, from self-catering advanced equipment and facilities with the expertise of highly apartments to luxury hotels. When considering where to stay, it’s skilled practitioners. worth remembering that many hotels provide fully equipped The safe and friendly atmosphere also encourages athletes to fitness centres and health spas with qualified personnel - the bring families for an enjoyable break in the sun. Great restaurants, ideal way to train and relax. friendly cafes and great beaches make Cyprus the perfect place A gateway between Europe and the Middle East, Cyprus enjoys to unwind and relax. -

Successful Experience of Renewable Energy Development in Several Offshore Islands

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Energy Procedia 100 ( 2016 ) 8 – 13 3rd International Conference on Power and Energy Systems Engineering, CPESE 2016, 8-12 September 2016, Kitakyushu, Japan Successful experience of renewable energy development in several offshore islands Jhih-Hao Lina, Yuan-Kang Wub*, Huei-Jeng Lina aDepartment of Engineering Science and Ocean Engineering, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 10617, Taiwan bDepartment of Electrical Engineering, National Chung Cheng University, No.168, Sec. 1, University Rd., Chiayi 62102, Taiwan Abstract Islands incur more difficult and expensive energy supplies; many offshore islands, therefore, develop renewable energy to supply energy and reduce CO2 emissions. However, most of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar, are intermittent and variable sources of power. To overcome the integration problems, numerous islands have utilized several useful methods. For instance, the island of Gran Canaria applied the pumped storage systems to reutilize energy, and the island of Lolland developed renewable hydrogen community. The operation experience of these islands is extremely worthy to appreciate. This article introduces eight offshore islands and discusses about their present situations, policies, successful experience and challenges about renewable energy development. Those islands include Samso, Reunion, Cyprus, Crete, King Island, Agios Efstratios, Utsira and El Hierro. The successful experience on those islands can provide useful information for other islands for developing renewable energy. ©© 20162016 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by Elsevierby Elsevier Ltd. LtdThis. is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Peer-http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/review under responsibility of the organizing). -

Renewable Energy in Small Islands

Renewable Energy on Small Islands Second edition august 2000 Sponsored by: Renewable Energy on Small Islands Second Edition Author: Thomas Lynge Jensen, Forum for Energy and Development (FED) Layout: GrafiCO/Ole Jensen, +45 35 36 29 43 Cover photos: Upper left: A 55 kW wind turbine of the Danish island of Aeroe. Photo provided by Aeroe Energy and Environmental Office. Middle left: Solar water heaters on the Danish island of Aeroe. Photo provided by Aeroe Energy and Environmental Office. Upper right: Photovoltaic installation on Marie Galante Island, Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Photo provided by ADEME Guadeloupe. Middle right: Waiah hydropower plant on Hawaii-island. Photo provided by Energy, Resource & Technology Division, State of Hawaii, USA Lower right: Four 60 kW VERGNET wind turbines on Marie Galante Island, Guadeloupe, French West Indies. Photo provided by ADEME Guadeloupe. Printing: Vesterkopi Printing cover; Green Graphic No. printed: 200 ISBN: 87-90502-03-5 Copyright (c) 2000 by Forum for Energy and Development (FED) Feel free to use the information in the report, but please state the source. Renewable Energy on Small Islands – Second Edition August 2000 Table of Contents Table of Contents Foreword and Acknowledgements by the Author i Introduction iii Executive Summary v 1. The North Atlantic Ocean Azores (Portugal) 1 Canary Island (Spain) 5 Cape Verde 9 Faeroe Islands (Denmark) 11 Madeira (Portugal) 13 Pellworm (Germany) 17 St. Pierre and Miquelon (France) 19 2. The South Atlantic Ocean Ascension Island (UK) 21 St. Helena Island (UK) 23 3. The Baltic Sea Aeroe (Denmark) 25 Gotland (Sweden) 31 Samsoe (Denmark) 35 4. -

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo; See for Further Information

D6.16 Policy Recommendations Reports Strengthening European integration through the analysis of conflict discourses Revisiting the Past, Anticipating the Future 31 December 2020 RePAST Deliverable D6.16 Policy Recommendations for Cyprus Vicky Triga & Nikandros Ioannidis Cyprus University of Technology This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 769252 1 / 20 D6.16 Policy Recommendations Reports Project information Grant agreement no: 769252 Acronym: RePAST Title: Strengthening European integration through the analysis of conflict discourses: revisiting the past, anticipating the future Start date: May 2018 Duration: 36 months (+ extension of 6 months) Website: www.repast.eu Deliverable information Deliverable number and name: D6.16 Policy recommendations reports for each of the countries (8) and the EU in general (1) for addressing the troubled past(s) Work Package: WP6 Dissemination, Innovation and Policy Recommendations / WP6.6 Developing Policy Recommendations (Activity 6.6.1 Developing roadmaps for the countries and the EU to address the issues arising from the troubled past(s) Lead Beneficiary: Vesalius College/University of Ljubljana Version: 2.0 Authors: Vasiliki Triga, Nikandros Ioannidis Submission due month: October 2020 (changed to December 2020 due to Covid19 measures) Actual submission date: 31/12/2020 Dissemination level: Public Status: Submitted 2 / 20 D6.16 Policy Recommendations Reports Document history Versio Author(s) / Date Status -

Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, Ca

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Anthropology Honors College 5-2013 Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E. Donovan Adams University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_anthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Donovan, "Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E." (2013). Anthropology. 9. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_anthro/9 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E. An honors thesis presented to the Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of requirements for graduation with Honors in Anthropology and graduation from the Honors College. Donovan Adams Research Advisor: Stuart Swiny, Ph.D. March 2013 1 Abstract The Early Bronze Age of Cyprus is not a very well understood chronological period of the island for a variety of reasons. These include: the inaccessibility of the northern part of the island after the Turkish invasion, the lack of a written language, and the fragility of Cypriot artifacts. Many aspects of protohistoric Cypriot life have become more understood, such as: the economic structure, social organization, and interactions between Cyprus and Anatolia. -

The Cyprus Sport Organisation and the European Union

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................ 2 1. THE ESSA-SPORT PROJECT AND BACKGROUND TO THE NATIONAL REPORT ............................................ 4 2. NATIONAL KEY FACTS AND OVERALL DATA ON THE LABOUR MARKET ................................................... 8 3. THE NATIONAL SPORT AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY SECTOR ...................................................................... 13 4. SPORT LABOUR MARKET STATISTICS ................................................................................................... 26 5. NATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM .................................................................................. 36 6. NATIONAL SPORT EDUCATION AND TRAINING SYSTEM ....................................................................... 42 7. FINDINGS FROM THE EMPLOYER SURVEY............................................................................................ 48 8. REPORT ON NATIONAL CONSULTATIONS ............................................................................................ 85 9. NATIONAL CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................... 89 10. NATIONAL ACTION PLAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................... 92 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................................................... -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

"South for Growth"

"South for Growth" An event organised by the European Parliament Information Office in Greece, in cooperation with the European Parliament Information Offices in Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain Megaron Athens Concert Hall Dimitris Mitropoulos Hall, Vassilisis Sofias & Kokkali Monday, 4 November 2013 PROGRAMME 09:00 Registration of participants 09:30 Welcome Address Leonidas ANTONAKOPOULOS Head, EP Information Office in Greece The South for Growth Initiative Constantinos TSOUTSOPLIDES Press Officer, EP Information Office in Greece 09:40 The Greek Government Kostis CHATZIDAKIS Minister of Development 09:55 Keynote Speaker Martin SCHULZ President of the European Parliament 10:15 Questions to the President 10:45 European Elections 2014: the political context Anni PODIMATA Vice President of the European Parliament, Responsible for Communication 11:00 PANEL I How to overcome the crisis and launch economic recovery Moderator: Ilias SIAKANTARIS Skai TV (Greece) Maria Da Graça CARVALHO Member of the European Parliament, European People's Party, Portugal Angelos STANGOS Kathimerini, Greece Salvatore IACOLINO Member of the European Parliament, European People's Party, Italy Thodoros SKYLAKAKIS Member of the European Parliament, Alliance of Liberal and Democrats for Europe, Greece Valeria DE ROSA Radio24 ilsole24ore, Italy Takis HADJIGEORGIOU Member of the European Parliament, European United Left - Nordic Green Left, Cyprus 12:30 Coffee Break 12:45 PANEL II How EU policies can fuel growth Moderator: Aristotelia PELONI Ta Nea, Greece Marietta -

The Social Dialogue in Professional Football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy )

The Social Dialogue in professional football at European and National Level ( Cyprus and Italy ) By Dimitra Theodorou Supervisor: Professor Dr. Roger Blanpain Second reader: Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus Tilburg University LLM International and European Labour Law TILBURG 2013 1 Dedicated to: My own ‘hero’, my beloved mother Arsinoe Ioannou and to the memory of my wonderful grandmother Androulla Ctoridou-Ioannou. Acknowledgments: I wish to express my appreciation and gratitude to my honored Professor and supervisor of this Master Thesis Dr. Roger Blanpain and to my second reader Dr. S.F.H.Jellinghaus for all the support and help they provided me. This Master Thesis would not have been possible if I did not have their guidance and valuable advice. Furthermore, I would like to mention that it was an honor being supervised by Professor Dr. R. Blanpain and have his full support from the moment I introduced him my topic until the day I concluded this Master Thesis. Moreover, I would like to address special thanks to Mr. Spyros Neofitides, the president of PFA, and Mr. Stefano Sartori, responsible for the trade union issues and CBAs in the AIC, for their excellent cooperation and willingness to provide as much information as possible. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Michele Colucci, who introduced me to Sports Law and helped me with my research by not only providing relevant publications, but also by introducing me to Mr. Stefano Sartori. Last but not least, I want to thank all my friends for their support and patience they have shown all these months.