Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the Styles and Techniques of French Master Carvers and Gilders

LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F SEPTEMBER 15, 2015–JANUARY 3, 2016 What makes a frame French? Discover the styles and techniques of French master carvers and gilders. This magnificent frame, a work of art in its own right, weighing 297 pounds, exemplifies French style under Louis XV (reigned 1723–1774). Fashioned by an unknown designer, perhaps after designs by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (French, 1695–1750), and several specialist craftsmen in Paris about 1740, it was commissioned by Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, a powerful French legal official, to accentuate his exceptionally large pastel portrait and its heavy sheet of protective glass. On this grand scale, the sweeping contours and luxuriously carved ornaments in the corners and at the center of each side achieve the thrilling effect of sculpture. At the top, a spectacular cartouche between festoons of flowers surmounted by a plume of foliage contains attributes symbolizing the fair judgment of the sitter: justice (represented by a scale and a book of laws) and prudence (a snake and a mirror). PA.205 The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F Frames are essential to the presentation of paintings. They protect the image and permit its attachment to the wall. Through the powerful combination of form and finish, frames profoundly enhance (or detract) from a painting’s visual impact. The early 1600s through the 1700s was a golden age for frame making in Paris during which functional surrounds for paintings became expressions of artistry, innovation, taste, and wealth. The primary stylistic trendsetter was the sovereign, whose desire for increas- ingly opulent forms of display spurred the creative Fig. -

Kalopsidha: Forty-Six Years After SIMA Volume 2

7 Kalopsidha: forty-six years after SIMA volume 2 Jennifer M. Webb A report on the excavations at Kalopsidha Tsaoudhi part of a volume devoted to Åström’s excavations Chiflik was published by Paul Åström in the second in 1959 at Kalopsidha and Ayios Iakovos (Åström volume of SIMA (Åström 1966). My own copy, which 1966: 7–143). In addition to the description of the has been in my possession since 1974 (the year in site and finds, it contains chapters by Åström on which I first met Paul), is now frayed and missing its Cypriot Bronze Age pot marks (Part III) and Middle back cover. In focusing on this volume, the first of over and Late Cypriot Plain White Hand-made ware relief 40 which Paul authored, co-authored or edited for bands (Part IV), each of which provides a corpus of SIMA, my intention is to trace the history of this site all material available at that time. There are also 11 within and beyond the SIMA corpus – with respect to specialist reports and the description of the tombs and both the archaeological record and its interpretation – discussion of Bronze Age pottery include ‘comments’ and to consider the enduring value of site reports and by Merrillees and Popham. The publication stands out those who support their publication. Kalopsidha was as an early example of a multidisciplinary site report occupied through most of the Bronze Age. It is typical and a testament to the collaborative spirit which Paul of many sites in Cyprus which have been investigated always showed toward other scholars. -

Master Thesis-Cyprus.Final

MORTUARY PRACTICES IN LC CYPRUS A Comparative Study Between Tombs at Hala Sultan Tekke and Other LC Bronze Age Sites in Cyprus Marcus Svensson Supervisor: Lovisa Brännstedt Master’s Thesis in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History Spring 2020 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Lund University Abstract This thesis investigates differences and similarities in the funerary material of Late Bronze Age Cyprus in order to answer questions about a possible uniqueness of the pit/well tombs at the Late Bronze Age harbour city of Hala Sultan Tekke. The thesis also tries to explain why these features stand out as singular, compared to the more common chamber tomb, and the reason for their existence. The thesis concludes that although no direct match to the pit/well tombs can be found in Cyprus, there are features that might have had enough similarities to be categorised as such, but since the documentation methods of the time were too poor one cannot say for certain. The thesis also gives an explanation of why not more of these features appear in the funerary material in Cyprus, and the answer is simply that the pit/well tombs were not considered to be tombs but wells. Furthermore, direct parallels to the pit/well tombs can be found on mainland Greece, first and foremost at the south room of the North Megaron of the Cyclopean Terrace Building at Mycenae but also at the Athenian Agora. Key Words Hala Sultan Tekke, Late Cypriote Bronze Age, pit/well tombs, chamber tombs, shaft graves, Mycenae. Acknowledgements This thesis is entirely dedicated to the team of the New Swedish Cyprus Expedition, especially Jacek Tracz who helped me restore the assembled literature in a time of need, and to Anton Lazarides for proofreading. -

Annual Report of the Department of Antiquities for the Year 2009

REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS AND WORKS ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTIQUITIES FOR THE YEAR 2009 PRINTED AT THE PRINTING OFFICE OF THE REPUBLIC OF CYPRUS LEFKOSIA 2013 ISSN 1010–1136 SENIOR STAFF OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTIQUITIES, AS ON 31 st DECEMBER 2009 1. ADMINISTRATION: Director: Pavlos Flourentzos ( until 31st October 2009 ), M.A. in Classical Archaeology and History of Art ( Charles University in Prague), Ph.D. ( Charles University in Prague). 2. CURATORS OF ANTIQUITIES: Maria Hadjicosti ( Acting Director in November 2009), M.A. in Classical Archaeology and History ( Charles University in Prague), Ph.D. (Charles University in Prague). Marina Solomidou-Ieronymidou ( Acting Director in December 2009 ), D.E.U.G., Licence, Maîtrise, D.E.A. in Archaeology (Université Sorbonne-Paris IV), Doctorat in Medieval Archaeology (Université Sorbonne-Paris I) . 3. SENIOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL OFFICERS : Despo Pilid es , B.A. (Hons) in Archaeology (Institute of Archaeology, London), Ph.D. in Archaeol - ogy (University College London). Eleni Procopiou, B.A. in History and Archaeology (National Capodistrian University of Athens), Ph.D. in Byzantine Archaeology (National Capodistrian University of Athens). 4. ARCHAEOLOGICAL OFFICERS: George Philotheou, B.A. in History and Archaeology ( National Capodistrian University of Athens), D.E.A. in Byzantine Archaeology (Université Sorbonne-Paris I) . Eftychia Zachariou- Kaila , M.A. in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History (Westfälische Wilhelms Universität Münster). Evi Fiouri, Licence and Maîtrise in Archaeology and History of Art (Université Pantheon-Sor - bonne, Paris I). Giorgos Georgiou B.A. in History and Archaeology (National Capodistrian University of Athens), Ph.D. in Archaeology (University of Cyprus). Eustathios Raptou, D.E.U.G., Licence, Maîtrise, D.E.A. -

THE PASSAGE of LOTUS ORNAMENT from EGYPTIAN to THAI a Study of Origin, Metamorphosis, and Influence on Traditional Thai Decorative Ornament

The Bulletin of JSSD Vol.1 No.2 pp.1-2(2000) Original papers Received November 13, 2013; Accepted April 8, 2014 Original paper THE PASSAGE OF LOTUS ORNAMENT FROM EGYPTIAN TO THAI A study of origin, metamorphosis, and influence on traditional Thai decorative ornament Suppata WANVIRATIKUL Kyoto Institute of Technology, 1 Hashigami-cho, Matsugasaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8585, Japan Abstract: Lotus is believed to be the origin of Thai ornament. The first documented drawing of Thai ornament came with Buddhist missionary from India in 800 AD. Ancient Indian ornament received some of its influence from Greek since 200 BC. Ancient Greek ornament received its influence from Egypt, which is the first civilization to create lotus ornament. Hence, it is valid to assume that Thai ornament should have origin or some of its influence from Egypt. In order to prove this assumption, this research will divine into many parts. This paper is the first part and serves as a foundation part for the entire research, showing the passage, metamorphosis and connotation of Thai ornament from the lotus ornament in Egypt. Before arriving in Thailand, Egyptian lotus had travelled around the world by mean of trade, war, religious, colonization, and politic. Its concept, arrangement and application are largely intact, however, its shape largely altered due to different culture and belief of the land that the ornament has travelled through. Keywords: Lotus; Ornament; Metamorphosis; Influence; Thailand 1. Introduction changing of culture and art. Traditional decorative Through the long history of mankind, the traditional ornament has also changed, nowadays it can be assumed decorative ornament has originally been the symbol of that the derivation has been neglected, the correct meaning identifying and representing the nation. -

Acanthus a Stylized Leaf Pattern Used to Decorate Corinthian Or

Historical and Architectural Elements Represented in the Weld County Court House The Weld County Court House blends a wide variety of historical and architectural elements. Words such as metope, dentil or frieze might only be familiar to those in the architectural field; however, this glossary will assist the rest of us to more fully comprehend the design components used throughout the building and where examples can be found. Without Mr. Bowman’s records, we can only guess at the interpretations of the more interesting symbols used at the entrances of the courtrooms and surrounding each of the clocks in Divisions 3 and 1. A stylized leaf pattern used to decorate Acanthus Corinthian or Composite capitals. They also are used in friezes and modillions and can be found in classical Greek and Roman architecture. Amphora A form of Greek pottery that appears on pediments above doorways. Examples of the use of amphora in the Court House are in Division 1 on the fourth floor. Atrium Inner court of a Roman-style building. A top-lit covered opening rising through all stories of a building. Arcade A series of arches on pillars. In the Middle Ages, the arches were ornamentally applied to walls. Arcades would have housed statues in Roman or Greek buildings. A row of small posts that support the upper Balustrade railing, joined by a handrail, serving as an enclosure for balconies, terraces, etc. Examples in the Court House include the area over the staircase leading to the second floor and surrounding the atria on the third and fourth floors. -

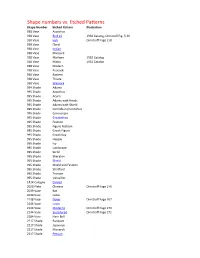

Shape Numbers Vs. Etched Patterns Shape Number Etched Pattern Illustration 938 Vase Acanthus 938 Vase Bird #1 1932 Catalog, Dimitroff Fig

Shape numbers vs. Etched Patterns Shape Number Etched Pattern Illustration 938 Vase Acanthus 938 Vase Bird #1 1932 Catalog, Dimitroff Fig. 5.36 938 Vase Fish Dimitroff Page 278 938 Vase Floral 938 Vase Indian 938 Vase Mansard 938 Vase Marlene 1932 Catalog 938 Vase Matzu 1932 Catalog 938 Vase Modern 938 Vase Peacock 938 Vase Racient 938 Vase Thistle 938 Vase Warwick 954 Shade Adams 995 Shade Acanthus 995 Shade Acorn 995 Shade Adams with Heads 995 Shade Adams with Shield 995 Shade Corinthian (Corinthia) 995 Shade Cornucopia 995 Shade Elizabethan 995 Shade Festoon 995 Shade Figure Festoon 995 Shade Greek Figure 995 Shade Greek Key 995 Shade Hepple 995 Shade Ivy 995 Shade Landscape 995 Shade Scroll 995 Shade Sheraton 995 Shade Shield 995 Shade Shield and Festoon 995 Shade Stratford 995 Shade Trenton 995 Shade Versailles 1414 Cologne Carved 2028 Plate Chinese Dimitroff Page 276 2039 Vase Bat 2039 Vase Lotus 2138 Vase Dover Dimitroff Page 267 2144 Vase Lotus 2144 Vase Moderne Dimitroff Page 270 2144 Vase Sculptured Dimitroff Page 271 2184 Vase Hare Bell 2217 Shade Banquet 2217 Shade Japanese 2217 Shade Monarch 2217 Shade Persian 2217 Shade Raised Leaf 2228 Shade Figure, Dancing 2241 Shade Leaf 2247 Shade Adams 2247 Shade Rennaisance 2249 Shade Rennaisance 2279 Shade Shield and Festoon 2292 Shade Adams Head 2292 Shade Warwick 2311 Shade Adams 2328 Shade Cupid 2328 Shade Festoon with Heads 2328 Shade Greek Figure 2328 Shade Ivy Leaf 2346 Shade Adams Rosette 2346 Shade Figure Rosette 2346 Shade Georgian 2346 Shade Gothic 2346 Shade Kenilworth -

Plant Motifs on Jewish Ossuaries and Sarcophagi in Palestine in the Late Second Temple Period: Their Identification, Sociology and Significance

PLANT MOTIFS ON JEWISH OSSUARIES AND SARCOPHAGI IN PALESTINE IN THE LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD: THEIR IDENTIFICATION, SOCIOLOGY AND SIGNIFICANCE A paper submitted to the University of Manchester as part of the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Humanities 2005 by Cynthia M. Crewe ([email protected]) Biblical Studies Melilah 2009/1, p.1 Cynthia M. Crewe CONTENTS Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 Plant Species 1. Phoenix dactylifera (Date palm) ....................................................................................................6 2. Olea europea (Olive) .....................................................................................................................11 3. Lilium candidum (Madonna lily) ................................................................................................17 4. Acanthus sp. ..................................................................................................................................20 5. Pinus halepensis (Aleppo/Jerusalem pine) .................................................................................24 6. Hedera helix (Ivy) .........................................................................................................................26 7. Vitis vinifera -

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople During the Frankish Era (1196-1303)

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 UMI Number: U585150 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585150 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis provides an analytical presentation of the situation of the Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the earlier part of the Frankish Era (1196 - 1303). It examines the establishment of the Latin Church in Constantinople, Cyprus and Achaea and it attempts to answer questions relating to the reactions of the Greek Church to the Latin conquests. -

Cyprus and British Colonialism: a Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Ormationf

Peace and Conflict Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Decolonizing Through a Peace and Article 6 Conflict Studies Lens 5-2018 Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict ormationF Kristian Fics University of Manitoba, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fics, Kristian (2018) "Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Formation," Peace and Conflict Studies: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 6. DOI: 10.46743/1082-7307/2018.1441 Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs/vol25/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace & Conflict Studies at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace and Conflict Studies by an authorized editor of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Formation Abstract This article uses family systems theory and Bowen family systems psychotherapy concepts to understand the nature of conflict formation during British colonialism in Cyprus. In examining ingredients of the British colonial model through family systems theory, an argument is made regarding the multigenerational transmission of colonial patterns that aid in the perpetuation of the Cyprus conflict ot the present day. The ingredients of the British colonial model discussed include the homeostatic maintenance of the Ottoman colonial structure, a divide and rule policy through triangulation, the use of nationalism and triangulation in the Cypriot education system, political exploitation, and apartheid laws. Explaining how it centers on relationships and circular causality, nonsummativity and homeostasis reveals the useful nature of family systems theories in understanding conflict formation. -

Terrestrial Slugs (Gastropoda, Pulmonata) in the NATURA 2000 Areas of Cyprus Island

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 174: 63–77 (2012) Slugs of Cyprus 63 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.174.2474 RESEARCH articLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Terrestrial slugs (Gastropoda, Pulmonata) in the NATURA 2000 areas of Cyprus island Katerina Vardinoyannis1, Simon Demetropoulos2, Moissis Mylonas1,3, Kostas A.Triantis4, Christodoulos Makris5, Gabriel Georgiou, Andrzej Wiktor6, Andreas Demetropoulos7 1 Natural History Museum of Crete, University of Crete, 71409 Herakleio Crete, Greece 2 Cyprus Wildlife Society, P.O.Box 24281, Lefkosia 1703, Cyprus 3 Department of Biology, University of Crete, 71409 He- rakleio Crete, Greece 4 Natural History Museum of Crete, University of Crete, 71409 Herakleio Crete, Greece 5 21 Ethnikis Antistaseos, 3022 Limassol, Cyprus 6 Museum of Natural History, Wrocław University, Sienkiewicza 21, 50-335 Wrocław, Poland 7 Cyprus Wildlife Society, P.O.Box 24281, Lefkosia 1703, Cyprus Corresponding author: Katerina Vardinoyannis ([email protected]) Academic editor: E. Neubert | Received 2 December 2011 | Accepted 22 February 2012 | Published 9 March 2012 Citation: Vardinoyannis K, Demetropoulos S, Mylonas M, Triantis KA, Makris C, Georgiou G, Wiktor A, Demetropoulos A (2012) Terrestrial slugs (Gastropoda, Pulmonata) in the NATURA 2000 areas of Cyprus island. ZooKeys 174: 63–77. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.174.2474 Abstract Terrestrial slugs of the Island of Cyprus were recently studied in the framework of a study of the whole ter- restrial malacofauna of the island. The present work was carried out in the Natura 2000 conservation areas of the island in 155 sampling sites over three years (2004–2007). Museum collections as well as literature references were included. -

BY ORDER of the SECRETARY of the AIR FORCE AIR FORCE INSTRUCTION 36-2803 18 DECEMBER 2013 Personnel the AIR FORCE MILITARY AWAR

BY ORDER OF THE AIR FORCE INSTRUCTION 36-2803 SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE 18 DECEMBER 2013 Personnel THE AIR FORCE MILITARY AWARDS AND DECORATIONS PROGRAM COMPLIANCE WITH THIS PUBLICATION IS MANDATORY ACCESSIBILITY: Publication and forms are available for downloading or ordering on e-Publishing website at: http://www.e-publishing.af.mil. RELEASABILITY: There are no releasibility restrictions on this publication. OPR: AFPC/DPSIDR Certified by: AF/A1S (Col Patrick J. Doherty) Supersedes: AFI36-2803, 15 June 2001 Pages: 235 This instruction implements the requirements of Department of Defense (DoD) Instruction (DoDI) 1348.33, Military Awards Program, and Air Force Policy Directive (AFPD) 36-28, Awards and Decorations Program. It provides Department of the Air Force policy, criteria, and administrative instructions concerning individual military decorations, service and campaign medals, and unit decorations. It prescribes the policies and procedures concerning United States Air Force awards to foreign military personnel and foreign decorations to United States Air Force personnel. This instruction applies to all Active Duty Air Force, Air Force Reserve (AFR), and Air National Guard (ANG) personnel and units. In collaboration with the Chief of Air Force Reserve (HQ USAF/RE) and the Director of the Air National Guard (NGB/CF), the Deputy Chief of Staff for Manpower, Personnel, and Services (HQ USAF/A1) develops policy for the Military Awards and Decorations Program. The use of Reserve Component noted in certain chapters of this Air Force Instruction (AFI) refers to the ANG and AFR personnel. Refer recommended changes and questions about this publication to the Office of Primary Responsibility (OPR) using the AF Form 847, Recommendation for Change of Publication; route AF Form 847s from the field through the Major Command (MAJCOM) publications/forms managers.