Encountering Nicaragua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

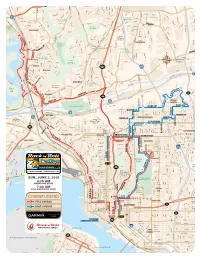

COURSE LEGEND L M T T G a N a a a a N H M a W Dr Ct H W a V 274 N R O E U Tol V I V O a P a a a D Ac E H If E Y I V V Ca E D D R E Ur St G Beadnell Way Armo a R F E

C a r d y a e Ca n n W n S o o in g n t r D i to D n S r n L c t o i u D e n c S n ate K n o r e g R a G i e l ow d l c g s A e C e id r v e w S v l e Co R e e f n mplex Dr d v a e a v l h B e l l ld t s A h o C J Triana S B a a A e t A e S J y d nt a s i a e t m v e gu e L r S h a s e e e R Ave b e t Lightwave d A A v L t z v a e M v D l A sa Ruffin Ct M j e n o r t SUN., JUNE 2, 2013 B r n e d n o Mt L e u a a M n r P b r D m s l a p l D re e a A y V i r r h r la tt r i C a t n Printwood Way i M e y r e d D D S C t r M v n a w I n C a d o C k Vickers St e 6:15 AM a o l l e Berwick Dr O r g c n t w m a e h i K i n u ir L i d r e i l a Engineer Rd J opi Pl d Cl a n H W r b c g a t i Olive Spectrum Center MARATHON STy ART m y e e Blvd r r e Ariane Dr a y o u o D u D l S A n L St Cardin Buckingham Dr s e a D h a y v s r a Grove R Soledad Rd P e n e R d r t P Mt Harris Dr d Opportunity Rd t W a Dr Castleton Dr t K r d V o e R b S i F a l a c 7:00 AM e l m Park e m e l w a Mt Gaywas Dr l P o a f l h a e D S l C o e o n HALF-MARATHON START t o t P r o r n u R n D p i i Te ta r ch Way o A s P B r Dagget St e alb B d v A MT oa t D o e v Mt Frissell Dr Arm rs 163 e u TIERRASANTA BLVD R e e s D h v v r n A A Etna r ser t t a our Av S y r B A AVE LBO C e i r e A r lla Dr r n o M b B i a J Q e e r Park C C L e h C o u S H a o te G M r Orleck St lga a t i C t r a t H n l t g B a p i S t E A S o COURSE LEGEND l M t t g a n a a a a n H a w M Dr Ct h w A v 274 n r o e u Tol v i v o a P A A a D ac e h if e y ica v v e D D r e ur St g Beadnell Way Armo -

Colonial Spanish Terms Compilation

COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS file:///C|/...20Grant%202013/Articles%20&%20Publications/Spanish%20Colonial%20Glossary/COLONIAL%20SPANISH%20TERMS.htm[5/15/2013 6:54:54 PM] COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES Second edition, 1998 Compiled and edited by: Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold Copyright, 1998 Published by: SHHAR PRESS, 1998 (Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research) P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 1-714-894-8161 Cover: Census Bookcover was provided by Ophelia Marquez . In 1791, and again in 1792, a census was ordered throughout the viceroyalty by Viceroy Conde de Revillagigedo. The actual returns came in during 1791 - 1794. PREFACE This pamphlet has been compiled in response to the need for a handy, lightweight dictionary of Colonial terms to use while reading documents. This is a supplement to the first edition with additional words and phrases included. Refer to pages 57 and 58 for the most commonly used phrases in baptismal, marriage, burial and testament documents. Acknowledgement Ophelia and Lillian want to record their gratitude to Nadine M. Vasquez for her encouraging suggestions and for sharing her expertise with us. Muy EstimadoS PrimoS, In your hands you hold the results of an exhaustive search and compilation of historical terms of Hispanic researchers. Sensing the need, Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Wold scanned hundreds of books and glossaries looking for the most correct interpretation of words, titles, and phrases which they encountered in their researching activities. Many times words had several meanings. -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

Presidio Visitor

THE PRESIDIO presidio.gov TRANSPORTATION Golden Gate Bridge PRESIDIGO SHUTTLE PUBLIC TRANSITDigital Terrian Mode Hillshadel (DTM_3FT.tif) - The DTM represents Fort Point he free PresidiGo Shuttle Three Muni busground routes currentlyelevations. serve This DTM is not National Historic Site Shuttle Routes Tis a great way to get to and the Presidio (withhydroflattened more coming soon): or hydroenforced. PACIFIC 2 PRESIDIO HILLS Route, Stop ID, + Direction stops at the Golden Gate 101 around the park. It has two routes. OCEAN SAN FRANCISCO BAY 28 DOWNTOWN Route + Stop ID PresidiGo Downtown provides Bridge Welcome Center 1 Torpedo Wharf Muni+ Golden Gate Transit service to and from key transit 29 stops at Baker Beach Golden Gate Bridge connections in San Francisco. N Welcome Center 30 Muni Lines and ID Numbers stops at Sports Basement 0 500 FT 1,000 FT Warming Hut Muni Stops Presidio Hills connects to 25 30 28 at Crissy Field 0 250 M Transfer Point for Muni or Golden Gate Transit Battery destinations within the park. East Vista Nearby Muni service: West Bluff West Bluff Picnic Area DOWNTOWN Route A Trail for Everyone (see reverse for information) East Beach 1 33 43 44 45 Coast Guard Pier Transit Center, the Letterman Length: 2.7 miles (4.3 km) Digital Arts Center, Van Ness Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail 28 Coastal Greater Farallones National Avenue and Union Street, Length: 2.7 miles (4.3 km) Batteries Marine Sanctuary BICYCLING Golden Gate Promenade / Bay Trail Length: 4.3 miles (6.9 km) Marina Embarcadero BART, and the Gate Marina District, Golden Crissy Marsh 30 Fort Mason, California Coastal Trail Gate 28 Crissy Field Salesforce Transit Center. -

(B. 1914). Papers, 1600–1976

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Max Leon Moorhead Collection Moorhead, Max Leon (b. 1914). Papers, 1600–1976. 18 feet. Historian. Correspondence (1962–1976); manuscripts (1960s); microfilmed and photocopied documents (1730–1790); research notes (n.d.); lectures (n.d.); student reports (n.d.); student research papers (n.d.); and printed materials (1853–1975), including book reviews and reprints, all relating to Moorhead’s teaching of Latin American history at the University of Oklahoma, and to his publications about Jacobo de Ugarte, the presidio, other Spanish colonial institutions in the Southwest, and the Indians of Mexico and the southwestern United States. Note: This collection is located at the Library Service Center. Materials must be requested in advance of a research visit. Please contact the Western History Collections at 405-325-3641 or via our website for assistance. Box 1 Europe and Latin America Folder: 1. Europe - containing notes 2. History (414 Reading Seminar in National Latin America) - individual reports 3. 414 Research Wars of Independence 4. 414 Research in National Period of Hispanic America 5. Early Modern Europe; a Selective Bibliography Box 2 Russian Influence in New Spain Folder: 1. Tompkins, Stuart R. and Moorhead, Max L., “Russia's Approach to America.” Reprinted from the British Columbia Historical Quarterly, April, July-October, 1949; 35 pp. 3 copies. 2. Russo-Spanish Conflict - containing notes Box 3 Interior Provinces of New Spain Folder: 1. Secretaria De Gobernacion, “Indice Del Ramo De Provincias Internas 1”; 254 pp. paperback by Archivo General De La Nacion, 1967. 2. Administrative Index of Mexico 3. Journal of the West; Vol. -

Presidio Coastal Trail Cultural Resource Survey

Presidio Coastal Trail Cultural Resource Survey Background This survey was prepared at the request of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy to provide information on known and possible cultural resources along the Fort Scott bluffs in preparation for the design of the Presidio Coastal Trail. This trail will be a link in the statewide California Coastal Trail. The California Coastal Conservancy oversees the statewide implementation efforts for developing the Coastal Trail, and provides this definition of the trail: “A continuous public right-of-way along the California Coastline; a trail designated to foster appreciation and stewardship of the scenic and natural resources of the coast through hiking and other complementary modes of non-motorized transportation.” (California Coastal Conservancy, 2001.) A “Presidio Trails and Bikeways Master Plan and Environmental Assessment” (aka “Trails Master Plan”) was developed jointly by the National Park Service and the Presidio Trust for that section of the Coastal Trail running through the Presidio of San Francisco, and was adopted through a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) in July 2003. The Trails Master Plan identified improvements needed to the California Coastal Trail in order to upgrade the existing route to a multi-use trail with associated bicycle lanes on Lincoln Boulevard and supporting components, such as trailheads and overlooks. This 3 mile Presidio trail section travels generally along the coastal bluffs, following Lincoln Boulevard. 1 The areas west and south of the Golden Gate Bridge/Highway 101 are known to have been the sites of important cultural activities over the past 200 years associated with the military and civilian histories of the Presidio of San Francisco. -

Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimería

Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimeria Alta, 1750-1800 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Waugh, Rebecca Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 10:54:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195118 PRESIDIO AND PUEBLO: MATERIAL EVIDENCE OF WOMEN IN THE PIMERÍA ALTA, 1750–1800 by Rebecca Jo Waugh Copyright © Rebecca Jo Waugh 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2005 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Rebecca Jo Waugh entitled Presidio and Pueblo: Material Evidence of Women in the Pimería Alta, 1750– 1800 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. J. Jefferson Reid, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. Teresita Majewski, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 4 May 2005 Dr. Thomas E. Sheridan, Ph.D. Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Ref. 2006 – TORRE ARGENTARIO

Ref. 2006 – TORRE ARGENTARIO Talamone – Grosseto – Tuscany www.romolini.co.uk/en/2006 Interiors Bedrooms Bathrooms Land 350 mq 5 4 48.0 ha Along the Tuscan Coastline, on the beautiful cliffs of Argentario not far from Talamone e Orbetel- lo, we find this 16th-century tower, finely restored and converted into a luxury home. The villa of- fers a total of 5 bedrooms and 4 bathrooms with beautiful outdoor spaces and terraces with breathtaking view over the sea. A stone staircase leads directly towards the sea from the garden. © Agenzia Romolini Immobiliare s.r.l. Via Trieste n. 10/c, 52031 Anghiari (AR) Italy Tel: +39 0575 788 948 – Fax: +39 0575 786 928 – Mail: [email protected] REFERENCE #: 2006 – TORRE ARGENTARIO TYPE: 16th-century tower on the sea CONDITIONS: restored LOCATION: right above the sea MUNICIPALITY: Talamone PROVINCE: Grosseto REGION: Tuscany INTERIORS: 350 square meters (3,766 square feet) TOTAL ROOMS: 10 BEDROOMS: 5 BATHROOMS: 4 MAIN FEATURES: stone walls with glacis, paved courtyard, stone vaulted, wooden beams, terra- cotta floors, sea view terraces, original fireplaces, staircase leading down to the seaside, possibility of building a helipad and a pool LAND: 48.0 hectares (118.6 acres) GARDEN: yes, well-maintained on the terraces ANNEXES: no ACCESS: well-maintained unpaved road SWIMMING POOL: no, but possible ELECTRICITY: already connected WATER SUPPLY: mains water TELEPHONE: already connected ADSL: yes GAS: municipal network HEATING SYSTEM: radiators Talamone (5km; 15’), Orbetello (27km; 40’), Porto Santo Stefano (28km; 45’), Grosseto (32km; 45’), Castiglione della Pescaia (52km; 1h), Terme di Saturnia (62km; 1h 15’), Tarquinia (74km; 1h 10’), Montalcino (86km; 1h 25’), Siena (106km; 1h 30’), Roma (173km; 2h 20’) Grosseto Baccarini (34km; 45’), Roma Fiumicino (153km; 1h 55’), Roma Ciampino (173km; 2h 10’), Firenze Peretola (187km; 2h 25’), Pisa Galilei (187km; 2h 15’), Perugia San Francesco (213km; 2h 40’) © Agenzia Romolini Immobiliare s.r.l. -

Hall of Maps Final Report

H A L L O F G E O G R A P H I C M A P S A P L A C E O F E X C E L L E N C E I N T H E U F F I Z I G A L L E R Y Originally, at the time of Vasari, this The Grand Duke wanted important historical space next to the room of Hugo scientific and mathematical instruments for van Der Goes that leads to it, was a covered astronomical and geographical knowledge to loggia of the Gallery overlooking the east be gathered in this place, with a celestial side of the Florence, with the majestic and a terrestrial globe. church of Santa Croce at its center. From the 1600s, the scientific instruments that belonged to Galileo Galilei were In 1589 Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ exhibited here as well, such as the Medici (1549 – 1609) decided to dedicate a telescopes, the geometric compass, the space to geography and cosmography in astrolabe, the globes, now exhibited at the homage to his father, Cosimo I, and to the Galileo Museum. Medici family's power. Closing the gallery's terrace with glass, it was possible to devote the room to the exhibition of scientific instruments of the Medici's collection. The room has a rectangular floor plan with a Both the West and North Walls are single entrance on the west side facing two decorated with large geographic maps, large windows. whereas on the South Wall a smaller map of On the walls, Ludovico Buti painted the the Island of Elba was added later; it was maps of Tuscany with the Florentine and originally set between two further windows, Sienese territories and the Island of Elba, which were walled up, when the adjacent based upon drawings made for this purpose gallery was built in place of the small in 1584 by the geographer and cartographer staircase, which used to connect the Stefano Bonsignori . -

Chapter 2: Exploring the Americas, 1400-1625

Exploring the Americas 1400–1625 Why It Matters Although the English have been the major influence on United States history, they are only part of the story. Beginning with Native Americans and continuing through time, people from many cultures came to the Americas. The Impact Today The Americas today consist of people from cultures around the globe. Native Americans, Spanish, Africans, and others discussed in Chapter 2 have all played key roles in shaping the culture we now call American. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 2 video, “Exploring the Americas,” presents the challenges faced by European explorers, and discusses the reasons they came to the Americas. 1513 • Balboa crosses the Isthmus of Panama 1492 1497 • Christopher Columbus • John Cabot sails to reaches America Newfoundland 1400 1450 1500 1429 c. 1456 • Joan of Arc defeats c. 1500 • Johannes Gutenberg the English at French • Songhai Empire rises in Africa uses movable metal town of Orléans • Rome becomes a major center type in printing of Renaissance culture 36 CHAPTER 2 Exploring the Americas Evaluating Information Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you learn about European exploration of the Americas. Step 1 Fold the paper from the top right corner down so the edges line up. Cut off the leftover piece. Fold a triangle. Cut off the extra edge. Step 2 Fold the triangle in half. Unfold. The folds will form an X dividing four equal sections. Step 3 Cut up one fold line and stop at the middle. Draw an X on one tab and label the other three. -

Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas

Volume 1997 Article 6 1997 Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Anne A. Fox Center for Archaeological Research Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Fox, Anne A. (1997) "Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1997, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1997.1.6 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1997/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1997/iss1/6 Test Excavations at the Spanish Governor's Palace, San Antonio, Texas Anne A. Fox with a contribution by Barbara A.