Presidio Coastal Trail Cultural Resource Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encountering Nicaragua

Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2011 ii Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History University of Oslo Spring 2011 iii iv Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Topic .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Research Questions ............................................................................................................................. 3 Delimitations ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The United States Marine Corps: a very brief history ......................................................................... 4 Historiography .................................................................................................................................... -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Goga Wrfr.Pdf

The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top: Golden Gate Bridge, Don Weeks Middle: Rodeo Lagoon, Joel Wagner Bottom: Crissy Field, Joel Wagner ii CONTENTS Contents, iii List of Figures, iv Executive Summary, 1 Introduction, 7 Water Resources Planning, 9 Location and Demography, 11 Description of Natural Resources, 12 Climate, 12 Physiography, 12 Geology, 13 Soils, 13 -

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

1 Coast Artillery Living History Fort

Coast Artillery Living History Fort Hancock, NJ On 20-22 May 2016, the National Park Service (NPS) conducted the annual spring Coast Defense and Ocean Fun Day (sponsored by New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium – (http://njseagrant.org/) in conjunction with the Army Ground Forces Association (AGFA) and other historic and scientific organizations. Coast Defense Day showcases Fort Hancock’s rich military heritage thru tours and programs at various locations throughout the Sandy Hook peninsula – designated in 1982 as “The Fort Hancock and Sandy Hook Proving Ground National Historic Landmark”. AGFA concentrates its efforts at Battery Gunnison/New Peck, which from February to May 1943 was converted from a ‘disappearing’ battery to a barbette carriage gun battery. The members of AGFA who participated in the event were Doug Ciemniecki, Donna Cusano, Paul Cusano, Chris Egan, Francis Hayes, Doug Houck, Richard King, Henry and Mary Komorowski, Anne Lutkenhouse, Eric Meiselman, Tom Minton, Mike Murray, Kyle Schafer, Paul Taylor, Gary Weaver, Shawn Welch and Bill Winslow. AGFA guests included Paul Casalese, Erika Frederick, Larry Mihlon, Chris Moore, Grace Natsis, Steve Rossi and Anthony Valenti. The event had three major components: (1) the Harbor Defense Lantern Tour on Friday evening; (2) the Fort Hancock Historic Hike on Saturday afternoon and (3) Coastal Defense Day on Sunday, which focused on Battery Gunnison/New Peck operations in 1943, in conjunction with Ocean Fun Day. The educational objective was to provide interpretation of the Coast Artillery mission at Fort Hancock in the World War Two-era with a focus on the activation of two 6” rapid fire M1900 guns at New Battery Peck (formerly Battery Gunnison). -

6-Ingh Barbette . Carriage Model of 1910

1073 1073 • SERVICE HANDBOOK_ OF THE 6-INGH BARBETTE . CARRIAGE MODEL OF 1910 FOR 6-INCH GU- NO MODEL OF 1908 Mu PREPARED IN THE OFFICE Of' THE CHIEF OF ORDNANCE May, 1923 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1922 1073 1073 SERVICE HANDBOOK OF THE 6-INCH BARBFYFFE CAR IAGH MODEL OF 1910 FOR 6-INCH GUNS MODEL OF 1908 Mil PREPARED IN THE OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF ORDNANCE May, 1921 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1922 WAR DEPARTMENT Document No. 1073 Office of The Adjutant General NOTE.-This document supersedes Ordnance Pamphlet No. 1713. WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, May 31,1921. The following publication, entitled "Service Handbook of the 6-inch Barbette Carriage, Model of 1910 for 6-inch Guns, Model of 1908 Mu," is published for the information and guidance of all concerned. • [062.1, A. G. O.] BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF WAR: PEYTON C. MARCH, Major General, Chiqfof Staff: OFFICIAL: P. C. HARRIS, The Adjutant General. (3) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page. 6 List of plates 7 General description 7 Emplacement 7 The carriage 7 Principal parts 7 Pedestal Pivot yoke 8 Cradle 9. Recoil and counterrecoil system 10 Gunner's platforms 10 Elevating mechanism 10 Range disk 11 Traversing mechanism 12 Sight 12 Shield and supports 12 Gas-ejector system 13 Electrical fittings, cables, and wiring 14 Lighting circuits 15 The firing circuits 15 Shot trucks 16 Shot barrows 16 Instructions for assembling the carriage 19 Care of the carriage Generalinstructions 19 Oil holes 19 20 To pack a stuffing box 20 Instructions for cleaning recoil cylinders 21 Approximate weight of principal parts of carriage 22 List of articles packed in armament chest List of parts 23 (5) LIST OF PLATES. -

Presidio of San Francisco an Outline of Its Evolution As a U.S

Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California NOV 1CM992 . Special History Study Presidio of San Francisco An Outline of Its Evolution as a U.S. Army Post, 1847-1990 August 1992 Erwin N. Thompson Sally B. Woodbridge Presidio of San Francisco GOLDEN GATE National Recreation Area California United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Denver Service Center "Significance, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder" Brian W. Dippie Printed on Recycled Paper CONTENTS PREFACE vii ABBREVIATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNINGS, 1846-1861 5 A. Takeover 5 B. The Indians 8 C. The Boundaries 9 D. Adobes, Forts, and Other Matters 10 CHAPTER 2: CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865 21 A. Organizing 21 B. Keeping the Peace 22 C. Building the Post 23 CHAPTER 3: THE PRESIDIO COMES OF AGE, 1866-1890 31 A. Peacetime 31 B. The Division Comes to the Presidio 36 C. Officers' Club, 20 46 D. Other Buildings 47 E. Troop Duty 49 F. Fort Winfield Scott 51 CHAPTER 4: BEAUTIFICATION, GROWTH, CAMPS, EARTHQUAKE, FORT WINFIELD SCOTT, 1883-1907 53 A. Beautification 53 B. Growth 64 C. Camps and Cantonments 70 D. Earthquake 75 E. Fort Winfield Scott, Again 78 CHAPTER 5: THE PRESIDIO AND THE FORT, 1906-1930 81 A. A Headquarters for the Division 81 B. Housing and Other Structures, 1907-1910 81 C. Infantry Terrace 84 D. Fires and Firemen 86 E. Barracks 35 and Cavalry Stables 90 F. -

Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan Environmental Assessment

1. Introduction The Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan and Environmental Assessment is a cooperative effort between the Presidio Trust (Trust), the National Park Service (NPS), and the Golden Gate National Parks Association (GGNPA). The Presidio Trust is a wholly- owned federal government corporation whose purposes are to preserve and enhance the Presidio as a national park, while at the same time ensuring that the Presidio becomes financially self-sufficient by 2013. The Trust assumed administrative jurisdiction over 80 percent of the Presidio on July 1, 1998, and the NPS retains jurisdiction over the coastal areas. The Trust is managed by a seven-person Board of Directors, on which a Department of Interior representative serves. NPS, in cooperation with the Trust, provides visitor services and interpretive and educational programs throughout the Presidio. The Trust is lead agency for environmental review and compliance under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). GGNPA is administering project funds and coordinating phase one of the project. The San Francisco International Airport has provided $500,000 to fund the first phase of the Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan under the terms and conditions outlined within the Cooperative Agreement for the Restoration of Mountain Lake, 24 July 1998. The overall goal of the Mountain Lake Enhancement Plan is to improve the health of the lake and adjacent shoreline and terrestrial environments within the 14.25-acre Project Area. This document analyzes three site plan alternatives (Alternatives 1, 2, and 3) and a no action alternative. It is a project-level EA that is based upon the Presidio Trust Act and the 1994 General Management Plan Amendment for the Presidio of San Francisco (GMPA) prepared by the NPS, a planning document that provides guidelines regarding the management, use, and development of the Presidio. -

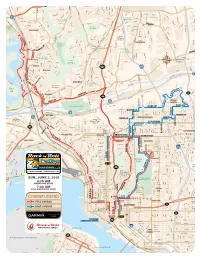

COURSE LEGEND L M T T G a N a a a a N H M a W Dr Ct H W a V 274 N R O E U Tol V I V O a P a a a D Ac E H If E Y I V V Ca E D D R E Ur St G Beadnell Way Armo a R F E

C a r d y a e Ca n n W n S o o in g n t r D i to D n S r n L c t o i u D e n c S n ate K n o r e g R a G i e l ow d l c g s A e C e id r v e w S v l e Co R e e f n mplex Dr d v a e a v l h B e l l ld t s A h o C J Triana S B a a A e t A e S J y d nt a s i a e t m v e gu e L r S h a s e e e R Ave b e t Lightwave d A A v L t z v a e M v D l A sa Ruffin Ct M j e n o r t SUN., JUNE 2, 2013 B r n e d n o Mt L e u a a M n r P b r D m s l a p l D re e a A y V i r r h r la tt r i C a t n Printwood Way i M e y r e d D D S C t r M v n a w I n C a d o C k Vickers St e 6:15 AM a o l l e Berwick Dr O r g c n t w m a e h i K i n u ir L i d r e i l a Engineer Rd J opi Pl d Cl a n H W r b c g a t i Olive Spectrum Center MARATHON STy ART m y e e Blvd r r e Ariane Dr a y o u o D u D l S A n L St Cardin Buckingham Dr s e a D h a y v s r a Grove R Soledad Rd P e n e R d r t P Mt Harris Dr d Opportunity Rd t W a Dr Castleton Dr t K r d V o e R b S i F a l a c 7:00 AM e l m Park e m e l w a Mt Gaywas Dr l P o a f l h a e D S l C o e o n HALF-MARATHON START t o t P r o r n u R n D p i i Te ta r ch Way o A s P B r Dagget St e alb B d v A MT oa t D o e v Mt Frissell Dr Arm rs 163 e u TIERRASANTA BLVD R e e s D h v v r n A A Etna r ser t t a our Av S y r B A AVE LBO C e i r e A r lla Dr r n o M b B i a J Q e e r Park C C L e h C o u S H a o te G M r Orleck St lga a t i C t r a t H n l t g B a p i S t E A S o COURSE LEGEND l M t t g a n a a a a n H a w M Dr Ct h w A v 274 n r o e u Tol v i v o a P A A a D ac e h if e y ica v v e D D r e ur St g Beadnell Way Armo -

Battery Chamberlin U.S

National Park Service Battery Chamberlin U.S. Department of the Interior Golden Gate National Recreation Area Practice firing of an original 6-inch gun mounted on a disappearing carriage, around 1910. Baker Beach, 1905 A voice bellows, "Load!" Like integral bring forward the 100-lb. shell on a ladle, parts of the gun they are loading, followed by another with a long pole thirteen soldiers spring into action. The who rams the shell into the barrel's first yanks open the breechblock (door) breech. The bag of gunpowder is heaved at the rear of the barrel, allowing the in behind, and the breechblock is swung next to shove the seven-foot sponge in shut and locked. Still another soldier and out of the firing chamber. Two men trips a lever, and the gun springs up on massive arms, above the wall behind which it was hidden. The sergeant shouts "Fire!" and tugs on the long lanyard attached to the rear of the gun. There is a deafening boom, a tongue of flame, and a huge cloud of smoke! The shell speeds toward a target mounted on a raft seven miles out to sea. The gun recoils, swinging back and down, behind the wall of the battery the men stand poised to reload. Sweating in their fatigues, they silently thank the sea breeze for cooling them. Only thirty seconds have passed, and they are once again reloading the gun. Gun drill at Battery Chamberlin around 1942. One soldier loads the gun powder bag as San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library San Francisco History Center, another with shell ladle withdraws. -

100 Things to Do in San Francisco*

100 Things to Do in San Francisco* Explore Your New Campus & City MORNING 1. Wake up early and watch the sunrise from the top of Bernal Hill. (Bernal Heights) 2. Uncover antique treasures and designer deals at the Treasure Island Flea Market. (Treasure Island) 3. Go trail running in Glen Canyon Park. (Glen Park) 4. Swim in Aquatic Park. (Fisherman's Wharf) 5. Take visitors to Fort Point at the base of the Golden Gate Bridge, where Kim Novak attempted suicide in Hitchcock's Vertigo. (Marina) 6. Get Zen on Sundays with free yoga classes in Dolores Park. (Dolores Park) 7. Bring Your Own Big Wheel on Easter Sunday. (Potrero Hill) 8. Play tennis at the Alice Marble tennis courts. (Russian Hill) 9. Sip a cappuccino on the sidewalk while the cable car cruises by at Nook. (Nob Hill) 10. Take in the views from seldom-visited Ina Coolbrith Park and listen to the sounds of North Beach below. (Nob Hill) 11. Brave the line at the Swan Oyster Depot for fresh seafood. (Nob Hill) *Adapted from 7x7.com 12. Drive down one of the steepest streets in town - either 22nd between Vicksburg and Church (Noe Valley) or Filbert between Leavenworth and Hyde (Russian Hill). 13. Nosh on some goodies at Noe Valley Bakery then shop along 24th Street. (Noe Valley) 14. Play a round of 9 or 18 at the Presidio Golf Course. (Presidio) 15. Hike around Angel Island in spring when the wildflowers are blooming. 16. Dress up in a crazy costume and run or walk Bay to Breakers.